Rose Zemelman Testimony Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ne-Yo Au Festival Mawazine

Communiqué de presse Rabat, 23 avril 2014 La dernière découverte du rap US à Mawazine Ne-Yo se produira en concert à Rabat le 04 juin 2014 L’Association Maroc Cultures a le plaisir de vous annoncer la venue du chanteur américain Ne-Yo à l’occasion de la 13ème édition du Festival - Mawazine Rythmes du Monde. Ne-Yo se produira mercredi 04 juin 2014 sur la scène de l’OLM-Souissi à Rabat. Dernière découverte du prestigieux label Def Jam, dont l’histoire se confond en grande partie avec celle du rap américain, Ne-Yo (né Shaffer Smith) a hérité d’une voix unique en son genre, inspirée de Stevie Wonder et des plus grands noms de la soul. L’artiste a obtenu en 2008 le Grammy Award du meilleur album contemporain R&B et composé des tubes pour Beyoncé, Rihanna et Britney Spears. Né en 1979 à Los Angeles, Ne-Yo est élevé par une famille de musiciens et se passionne très tôt pour la musique. Ses idoles de l'époque s’appellent Whitney Houston et Michael Jackson. Au cours de cette période, le garçon développe une culture musicale importante, s’essaie au chant, à la composition et à l'écriture. Après plusieurs prestations réussies, Ne-Yo retient l'attention de Def Jam, le label le plus actif de la scène R&B. Avec lui, le chanteur enregistre les singles So Sick , Sexy Love et When You're Mad , qui reçoivent un accueil très favorable dans les clubs de la côte ouest. Ne-Yo sort en 2006 son premier album, In My Own Words , qui se vend à 1 million d’exemplaires. -

The Body and Posttraumatic Healing: a Teresian Approach

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 9, No. 1 (2020): 75-97 The Body and Posttraumatic Healing: A Teresian Approach Julia Feder HEN MANY PEOPLE THINK “mysticism” or “mystical prayer,” they imagine a dreamy kind of out-of-body ex- perience in which one encounters the Ultimate. For W those who have suffered from sexual violence, this ver- sion of prayer is, at best, not helpful and, at worst, dangerous. Because the threat of dissociation of the mind and the body is both debilitating and ever-present for trauma survivors, imagining prayer as a “mystical flight” away from the realm of bodies (both personal and social-polit- ical) is a terrible idea—both theologically and psychologically. The idea that mystical prayer might push one beyond or away from the body is psychologically dangerous because dissociation from one’s body is a costly mode of coping with trauma and bodily reintegration is extremely difficult once this breach has been rendered.1 For Chris- tian survivors of sexual violence, a conception of prayer as mystical flight is also poor theology because the Christian tradition is an incar- national tradition—one that centers revelation on the disclosure of God in flesh. According to the Christian tradition, prayer orients us more profoundly to God incarnate—God disclosed sacramentally in our lives, in history, in the world. Therefore, Christian prayer is always and everywhere an embodied practice. Teresa of Avila, the sixteenth-century Spanish saint and mystic, is one of the most celebrated authors describing the deep and enduring connection between the life of prayer and the body. -

So Sick Or So Cool? the Language of Youth on the Internet SALI A

Language in Society 45,1–32. doi:10.1017/S0047404515000780 So sick or so cool? The language of youth on the internet SALI A. TAGLIAMONTE IN COLLABORATION WITH DYLAN USCHER, LAWRENCE KWOK, AND STUDENTS FROM HUM199Y 2009 AND 2010 Department of Linguistics, University of Toronto 100 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT This article presents the results of a two-year study of North American youth which produced a 179,000 word corpus of internet language from the same writers across three registers: email, instant messaging, and phone texting. Analysis of three linguistic phenomena—(i) acronyms, short forms, and ini- tialisms; (ii) intensifiers; and (iii) future temporal reference—reveals that despite variation in form and contrasting frequencies across registers, the pat- terns of variant use are stable. This offers linguistic evidence that there is no degeneration of grammar in internet language use. Instead, the young people are fluidly navigating a complex set of new written registers, and they command them all. (Internet, language change, youth)* INTRODUCTION Research on language use on the internet is by now an industry complete with themes, factions, and fields of study (e.g. Androutsopolous 2014). Virtually all of this research, however, is based on what is publically available on the internet. What remains hidden is how people are interacting within each other INSIDE the in- ternet where one-on-one discourses are transpiring in a worldwide beehive of com- munication. What type of language do people use when they communicate with each other using device-based mediation, a phenomena referred to as CMC (com- puter-mediated communication) (Kiesler, Siegel, & McGuire 1984)? This is a ques- tion that seems simple enough, but when it comes to finding out, it soon becomes apparent that neither scientists, nor journalists, nor teachers are actually privy to the day-to-day interactions between people, as they tap away at their computers and phones. -

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Two New Orleans Stories

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-16-2003 My Kind of Music: Two New Orleans Stories Mary-Louise Ruth University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Ruth, Mary-Louise, "My Kind of Music: Two New Orleans Stories" (2003). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 16. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/16 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY KIND OF MUSIC: TWO NEW ORLEANS STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing by Mary-Louise Ruth B.A., University of New Orleans, 1970 Education Credential, St. Mary’s College, 1987 May 2003 Copyright 2003, Mary-Louise Ruth ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank all of my teachers and fellow students for their perceptive comments, criticisms and support which will inspire me for the rest of my life. -

The Deaf Movement and Musical Theater

The Deaf Movement and Musical Theater [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. Library podcasts are brought to you by The Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts, visit our web site at w w w dot SPL dot org. To learn how you can help the library foundation support The Seattle Public Library go to foundation dot SPL dot org [00:00:36] Welcome everyone. My name is Bob Tang the music librarian here at Seattle Public Library. And I want to thank you all for coming to this presentation Cole presentation with the library with Fifth Avenue theater for their production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. And without any further ado I'd like to welcome Orlando and Josh and E.J.. Hello. Hello. Mr.. Safe behind these windows and still. Gazing at the people down. On. My life as I write I'm hungry for the mysteries all my life I memorized things [00:01:31] Knowing Penn State will never know. [00:01:35] All my life I will wonder how it feels to the last day. Not above [00:01:52] Saying hey this is what I do. Just say [00:02:37] We send their wives through the roofs and see every day they shout scolding go about their life. [00:02:46] Keep this up they keep telling us to be bad. Or. Since [00:04:00] So my name is Orlando Miralis I am the Director of Education and Engagement at the Fifth Avenue theater. -

Psychotherapy and Traditional Healing for Ensuring the Access, Relevance, and Efficacy of Counseling Interventions for American Indian Populations

Major Contribution The Counseling Psychologist 38(2) 166 –235 Psychotherapy and © 2010 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. Traditional Healing sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0011000008330831 for American Indians: http://tcp.sagepub.com Exploring the Prospects for Therapeutic Integration Joseph P. Gone1 Abstract Multicultural advocates within professional psychology routinely call for “culturally competent” counseling interventions. Such advocates frequently cite and celebrate traditional healing practices as an important resource for developing novel integrative forms of psychotherapy that are distinctively tailored for diverse populations. Despite this interest, substantive descriptions of specific forms of traditional healing vis-à-vis psychotherapy have appeared infrequently in the psychology literature. This article explores the prospects for therapeutic integration between American Indian traditional healing and contemporary psychotherapy. Systematic elucidation of historical Gros Ventre healing tradition and Eduardo Duran’s (2006) culture-specific psychotherapy for American Indians affords nuanced comparison of distinctive therapeutic paradigms. Such comparison reveals significant convergences as well as divergences between these therapeutic traditions, rendering integration efforts and their evaluation extremely complex. Multicultural professional psychology would benefit from collaborative efforts undertaken with community partners, 1University of Michigan Corresponding Author: Joseph P. Gone, -

Audience Interpretations of the Representation of Women in Music Videos by Women Artists Libby Mckenna University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Audience interpretations of the representation of women in music videos by women artists Libby McKenna University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation McKenna, Libby, "Audience interpretations of the representation of women in music videos by women artists" (2006). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2624 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Audience Interpretations of the Representation of Women in Music Videos by Women Artists by Libby McKenna A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Derina Holtzhausen, Ph.D. Larry Z. Leslie, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 21, 2006 Keywords: cultural studies, feminism, mass media, popular culture, MTV music videos, women's studies © Copyright 2006, Libby McKenna Acknowledgments First and foremost thanks are due to my mentor, advisor, and thesis chair, Dr. Kim Golombisky, without whose guidance and encouragement this thesis would not be what it is today. Many thanks to Dr. Derina Holtzhausen, whose pioneering work aided my focus groups, and to Dr. Larry Leslie, grammar extraordinaire, who performed one of the first studies on MTV music videos. -

Don Robertson Interview Transcription

Don Robertson- Interview with Dr. Tara Hembrough and Noah Patton Link: https://youtu.be/UXvxfKYeLc0 Transcription completed by Noah Patton. TH: Hi, this is Dr. Tara Hembrough, and I'm at Southeastern Oklahoma State University today, and I'm here with Don. I'm going to let him introduce himself in a minute. I'm also here with Noah Patton. We're going to talk today with Don about his experiences in the military. Thank you for being here today. Don, can you introduce yourself to us? DR: Okay, I'm Don Robertson. I’ve lived here most of my life outside of the military. I'm 77 years old, and I wish I could go back to Germany. TH: Will you tell us a little bit about your military family history? Did you have any? DR: No, I never had anyone in the military except myself. Now I had a nephew that was in the Marine Corps. Believe me, I’ve seen pictures that he sent. Everything has changed, from the pictures he sent me. I said, “You know, it's not the same.” TH: What do you think is different? DR: Well, for instance, he showed me in his wall locker, and there's a bottle of whiskey in it. You didn't do that when I was in there. You didn't have alcohol in your wall locker. I saw right then it has changed. When I got to Germany, once a month we’d have what we called alert. It was liable to be Sunday morning at two o'clock. -

His First Album Went Platinum and His Songs for Other Superstars Reached

THE WA MAKEYS HYOUE FEEL uccess—at any age—comes with itsS trials: the comparisons, the doubts (both self-inflicted and otherwise), the rumors, the expectations. After penning No. 1 hits for Mario and Beyoncé, starring in the $61 million box office hit Stomp The Yard and releasing his platinum- selling debut, In My Own Words, Ne-Yo has had his fair share of all of the above. “I didn’t take it very serious,” says the 24-year-old singer, referring right away to a magazine article headline that labeled him a sex addict. “I could think of worse things to be addicted to. I wasn’t really trippin’ until my mom called me on it His first album went platinum and people really started thinking I had and his songs for other a problem. So I was like, ‘Yo, read the UN HALL; VNER; article. Don’t just read the headline.’” superstars reached the top of Ne-Yo says he understands there’s hat the charts. Back for seconds, really nothing you can do. “Take the and whole gay rumor, for example. If I come WORDS RASHA NE-YO wants you to know why PHOTOGRAPHY MAGNUS UNNAR; out and go, ‘No, I am not gay! How dare FASHION EDITOR ALEX SLAVYCZ; GROOMER YUKA WASHIZU; PHOTO ASSISTANT LISA RO they do this to me? Blah, blah, blah...,’ THIS page: CARDIGAN WESC; he is, simply, the best singing T-SHIRT AMERICAN APPAREL; BEANIE D&G; SUNGLASSES DIOR HOMME; they go, ‘Oh, he’s getting defensive. It OPPOSITE page: T-SHIRT 10 DEEP; TRENCH COAT must be true!’ And if I say, ‘You know songwriter of his generation.. -

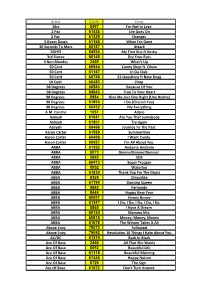

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam