Historic Properties Inventory (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

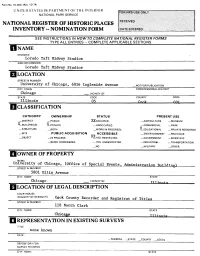

Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______I LOCATION

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______________________________ I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER University of Chicago, 6016 Ingleside Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 05 P.onV CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC XXOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS ^-EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAMEINAMt University of Chicago, (Office of Special Events, Administration STREET & NUMBER 5801 Ellis Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Chicago T1 1 inr>i' a LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEps.ETc. Cook County Recorder and Registrat of Titles STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Tllinm', REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none known DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE YY —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE XXQOOD —RUINS XXALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Lorado Taft's wife, Ada Bartlett Taft y described the Midway Studios in her biography of her husband, Lorado Taft, Sculptor arid Citizen; In 1906 Lorado moved his main studio out of the crowded Loop into a large, deserted brick barn on the University of Chicago property on the Midway. -

Chicago Venue Portfolio

CHICAGO2016 VENUE PORTFOLIO 1750 W. LAKE STREET CHICAGO, IL 60612 [email protected] 773.880.8044 PARAMOUNTEVENTSCHICAGO.COM Paramount Events is ready to help you plan a spectacular event with a delicious SET menu, but to truly make an impact, the perfect backdrop is absolutely essential. THE We have connections at some of the best venues in Chicago, including The Smith on Lake, our own private space that guarantees dedicated service and personalized attention. SCENE You’re welcome to explore the following pages, but don’t forget – we’re here for you! We know every location inside and out and will be happy to offer our suggestions as a guide. ENJOY! TABLE OF 19th Century Club 1 Garfield Park Conservatory 45 Park West 90 1st Ward at Chop Shop 2 Glessner House Museum 46 Parliament 91 CONTENTS 345 North 3 Goodman Theatre 47 Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum 92 360 Chicago 4 Gruen Galleries 48 Pittsfield Building 93 63rd Street Beach House 5 Harold Washington Library Center 49 Pleasant Home 94 A New Leaf 6 Harris Theatre 50 Portfolio Annex 95 Anita Dee Charters 7 Highland Park Community House 51 Power House 96 Aragon Ballroom 8 Hilton | Asmus Contemporary 52 Prairie Production 97 Artifact Events 9 Hinsdale Community House 53 Primitive Art 98 Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University 10 Humboldt Park & Boat House 54 Pritzker Military Museum & Library 99 Baderbräu 11 Ida Noyes Hall at University of Chicago 55 Promontory Point 100 Bentley Gold Coast 12 Ignite Glass Studios 56 Ravenswood Event Center 101 Berger Park 13 International -

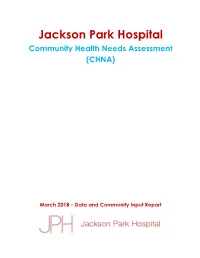

I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park

Jackson Park Hospital Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) March 2018 – Data and Community Input Report Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital 3 B. Defining Community for the CHNA 3 C. Community Health Needs Assessment Methods/Process 6 II. Health Status in the Community – Health Indicator Data 7 A. Social, Economic, and Structural Determinants of Health 7 B. Behavioral Health – Mental Health and Substance Use 19 C. Chronic Disease 24 D. Access to Care 39 III. Health Status in the Community – Community & Stakeholder Input 46 A. Community Focus Groups 46 B. Key Informant Interviews 49 IV. Health Status in the Community – Maps of Community Resources 51 V. Summary of Jackson Park Hospital’s Community Health 60 Implementation Activities – 2015-2018 A. Senior Healthcare Program 60 B. Community Partnerships and Outreach 61 C. Outpatient Services 62 D. In Development – Substance Abuse Program 63 Appendix A. Written Comments from Focus Group Participants 63 Appendix B. Focus Group Questions 64 2 I. Introduction A. Overview of Jackson Park Hospital Jackson Park Hospital & Medical Center is a 256-bed short-term comprehensive acute care facility serving the south side of Chicago for nearly 100 years. The hospital offers full medical, surgical, obstetric, psychiatric, and medical stabilization (detox) services as well as medical sub-specialties including cardiology, pulmonary, gastrointestinal disease, renal, orthopedics, ENT, ophthalmology, infectious disease, HIV, hematology/oncology and geriatrics. Quality ambulatory care is provided onsite through the family medicine center and senior health center. The hospital also provides medical education and training through its family medicine residency program and several affiliated medical schools. -

Obama Presidential Library the University of Chicago Adjaye Associates Contents I Urban Ii Library Iii Net-Zero Iv Design Approach in the Park Strategy Vision

OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ADJAYE ASSOCIATES CONTENTS I URBAN II LIBRARY III NET-ZERO IV DESIGN APPROACH IN THE PARK STRATEGY VISION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 2 I URBAN APPROACH OUR PROPOSAL RE-IMAGINES THE PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY TO BE THE FIRST TRUE URBAN LIBRARY. OPERATING ON MULTIPLE SCALES OF RENEWAL — INDIVIDUAL, URBAN, ECONOMIC, AND ECOLOGICAL — THE NEW LIBRARY ACTIVELY ENGAGES THE COMMUNITY WITH UPDATED INFRASTRUCTURE AND NEW BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE GENERATIONS OF THE SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO. OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 3 WASHINGTON PARK SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO WASHINGTON PARK • 7 MILES SOUTH OF THE LOOP • NEAR MIDWAY AIRPORT • HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT SITE • GATEWAY TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO • EASILY ACCESSIBLE BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 4 GARFIELD BOULEVARD HISTORICALLY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 5 GARFIELD BOULEVARD TODAY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 6 WASHINGTON PARK “LUNGS OF THE CITY” WASHINGTON PARK • CONSTRUCTED IN 1870’S • DR. JOHN RAUCH THE FOREFATHER OF THE CHICAGO PARK SYSTEM DESCRIBED IT AS “THE LUNGS OF THE CITY” • DESIGNED BY FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED & CALVERT VAUX • EARLY ATTRACTIONS TO THE PARK INCLUDED RIDING STABLES, CRICKET GROUNDS, BASEBALL FIELDS, A TOBOGGAN SLIDE, ARCHERY RANGES, A GOLF COURSE, BICYCLE PATHS, ROW BOATS, -

Marshall Field's Department Store

Marshall Field’s Department Store – A Chicago Landmark Long before Nordstrom’s developed their “easy return” policy, Marshall Field’s was famous for their unconditional returns. The upscale department store of the gilded age is also credited with the retail dictums “Give the Lady What She Wants” and “The Customer Is Always Right.” On October 8, 1871, when the great Chicago fire broke out, company officials and employees worked round the clock to remove as much merchandise as possible, eventually working by the light of the approaching fire. When the city waterworks burned, any hope of saving the store was lost. So much merchandise had been saved, however, that the store was able to reopen temporarily in a horse car barn. I include the history because If you don’t understand how Marshall Field’s has been essential to Chicago for over a century, you can’t appreciate the disappointment people felt when it was purchased by Macy’s in 2005 and the name was changed. Chicagoans mourned the loss of a grand tradition. When I was a child, it was a huge treat to travel downtown to see their Christmas windows, and the tradition of the three story (45 ft) Christmas tree still prevails. As a child, you would nearly fall over trying to view the decorations at the very top. If we were “very good” (translation – when mom was exhausted) we might get to eat in the cafeteria, then naturally, rush to chocolate kitchen on the seventh floor to watch workers box Frango mints, while we inhaled the rich aroma of chocolate. -

St John's University Undergraduate Student Managed Investment Fund Presents: Target Corporation Stock Analysis November 11, 20

St John’s University Undergraduate Student Managed Investment Fund Presents: Target Corporation Stock Analysis November 11, 2003 Recommendation: Purchase 300 shares of Target stock at market value Industry: Retail Analysts: Jennifer Tang – [email protected] Michael Vida – [email protected] Share Data: Fundamentals: Price - $39.15 P/E (2/03) – 21.63 Date – November 6, 2003 P/E (2/04E) – 21.96 Target Price – $44.58 P/E (2/05E) – 22.95 52 Week Price Range – $25.60 - $41.80 Book Value/Share – $11.03 Market Capitalization – $35.40 billion Price/Book Value – $3.60 Revenue 2002 – $43.917 billion Dividend Yield – 0.72% Projected EPS Growth – 15% Shares Outstanding – 910.9 million ROE 2002 – 17.51% Stock Chart: Executive Summary After analyzing Target Corp’s financials, industry and future outlook, we recommend the purchase of 300 shares of the company’s stock at market order. As a leading discount retailer, only behind Walmart, Target has made considerable growth in the industry over the past few years. Target offers an array of merchandise from women’s apparel, household products, toys and even food. One of the strengths of Target lies in its development of private brands, which helps create a strong image of the store in the customers’ minds. The company is able to further lower its costs through direct sourcing, buying merchandise at lower prices and strengthening its bargaining position with suppliers. While Target Corp hasn’t seen as much success with its other operations of Marshall Fields and Mervyn’s as it has with its namesake store, the company plans to invest resources into these two areas to turn around results. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Promontory Point th other names/site number 55 Street Promontory Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 5491 South Shore Drive not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60615 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Historic Preservation Agency State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

A Greeting from Paul Cornell President of the Board of Directors, Augustana Heritage Association

THE AUGUS ta N A HERI ta GE NEWSLE tt ER VOLUME 5 SPRING 2007 NUMBER 2 A Greeting From Paul Cornell President of the Board of Directors, Augustana Heritage Association hautauqua - Augustana - Bethany - Gustavus – Chautauqua...approximately 3300 persons have attended these first five gatherings of the AHA! All C have been rewarding experiences. The AHA Board of Directors announces Gatherings VI and VII. Put the date on your long-range date book now. 2008 Bethany College Lindsborg, Kansas 19-22 June 2010 Augustana College Rock Island, Illinois 10-13 June At Gathering VI at Bethany, we will participate in the famous Midsummers Day activities on Saturday, the 21st. We will also remember the 200th anniversary of the birth of Lars Paul Cornell, President of the Board of Directors Paul Esbjorn, a pioneer pastor of Augustana. We are planning an opening event on Thursday evening, the 19th and concluding on of Augustana - Andover, Illinois and New Sweden, Iowa, and Sunday, the 22nd with a luncheon. 4) Celebrating with the Archbishop of the Church of Sweden in Gathering VII at Augustana will include: 1) Celebrating attendence. the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the Augustana I would welcome program ideas from readers of the AHA Synod, 2) Celebrating the anniversary of Augustana College Newsletter for either Bethany or Augustana. I hope to be present and Seminary, 3) Celebrating the two pioneer'. congregations at both events. How about YOU? AHA 1 Volume 5, Number 2 The Augustana Heritage Association defines, promotes, and Spring 2007 perpetuates the heritage and legacy of the Augustana Evangelical Lutheran Church. -

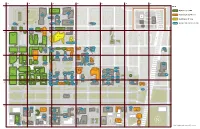

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

Insider's Guide

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

Fformer Fifth Ward Alderman Leon Despres, Who Received a Special

Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society Former Fifth Ward Hyde Park-Kenwood is the FAlderman Leon Despres, place that also nurtured and who received a special produced the first female Mrican Cornell Awardfrom the Hyde American V.S. Senator in the Park Historical Society at the person of Carol Moseley Braun. 2008 mem bership, dinner, The first black mayor of Chicago, concluded his acceptance the late Harold Washington, statement by reflecting upon was a resident of Hyde Park Hyde Parkers w ho had served in Kenwood. On January 20,2009, public office over the years. He President-Elect Barack Obama ended by saying that, {{next year will officially be sworn in as I m ight see a Hyde Parker in President of the V nited States by the White House." OnJ anuary the Chief J ustice of the V nited 20, w hen Hyde Parker and States Supreme Court. H owever, forme·r U. S. Senator Barack he has already begun to publicly Obama takes the oath of office, announce and present his choices this will be true at last. for important positions for his What follows are contributions administration. As he has publicly by several Society members stated very often, he intends to about the significance ofMr. "hit the ground running" on Obama's election victory. issues like foreign policy, jobs, taxes, housing, health, education, ;'ii Timuel D. Black, civil rights etc. As one who before he publicly leader, historian and educator launched his political career, advised him on tactics he could On November 4th, 2008, use in community organizing, I Hyde Park-Kenwood residents know that when he chooses "the and their friends could shout and ground" he wants to "run" on he yell wherever they were that one "runs" very fast in order to reach of their neighbors, V .S.