Meta-Representational Fluency: Math Majors' Visualization of the L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numerical Differentiation and Integration

Chapter 4 Numerical Di↵erentiation and Integration 4.1 Numerical Di↵erentiation In this section, we introduce how to numerically calculate the derivative of a function. First, the derivative of the function f at x0 is defined as f x0 h f x0 f 1 x0 : lim p ` q´ p q. p q “ h 0 h Ñ This formula gives an obvious way to generate an approximation to f x0 : simply compute 1p q f x0 h f x0 p ` q´ p q h for small values of h. Although this way may be obvious, it is not very successful, due to our old nemesis round-o↵error. But it is certainly a place to start. 2 To approximate f x0 , suppose that x0 a, b ,wheref C a, b , and that x1 x0 h for 1p q Pp q P r s “ ` some h 0 that is sufficiently small to ensure that x1 a, b . We construct the first Lagrange ‰ Pr s polynomial P0,1 x for f determined by x0 and x1, with its error term: p q x x0 x x1 f x P0,1 x p ´ qp ´ qf 2 ⇠ x p q“ p q` 2! p p qq f x0 x x0 h f x0 h x x0 x x0 x x0 h p qp ´ ´ q p ` qp ´ q p ´ qp ´ ´ qf 2 ⇠ x “ h ` h ` 2 p p qq ´ for some ⇠ x between x0 and x1. Di↵erentiating gives p q f x0 h f x0 x x0 x x0 h f 1 x p ` q´ p q Dx p ´ qp ´ ´ qf 2 ⇠ x p q“ h ` 2 p p qq „ ⇢ f x0 h f x0 2 x x0 h p ` q´ p q p ´ q´ f 2 ⇠ x “ h ` 2 p p qq x x0 x x0 h p ´ qp ´ ´ qDx f 2 ⇠ x . -

MPI - Lecture 11

MPI - Lecture 11 Outline • Smooth optimization – Optimization methods overview – Smooth optimization methods • Numerical differentiation – Introduction and motivation – Newton’s difference quotient Smooth optimization Optimization methods overview Examples of op- timization in IT • Clustering • Classification • Model fitting • Recommender systems • ... Optimization methods Optimization methods can be: 1 2 1. discrete, when the support is made of several disconnected pieces (usu- ally finite); 2. smooth, when the support is connected (we have a derivative). They are further distinguished based on how the method calculates a so- lution: 1. direct, a finite numeber of steps; 2. iterative, the solution is the limit of some approximate results; 3. heuristic, methods quickly producing a solution that may not be opti- mal. Methods are also classified based on randomness: 1. deterministic; 2. stochastic, e.g., evolution, genetic algorithms, . 3 Smooth optimization methods Gradient de- scent methods n Goal: find local minima of f : Df → R, with Df ⊂ R . We assume that f, its first and second derivatives exist and are continuous on Df . We shall describe an iterative deterministic method from the family of descent methods. Descent method - general idea (1) Let x ∈ Df . We shall construct a sequence x(k), with k = 1, 2,..., such that x(k+1) = x(k) + t(k)∆x(k), where ∆x(k) is a suitable vector (in the direction of the descent) and t(k) is the length of the so-called step. Our goal is to have fx(k+1) < fx(k), except when x(k) is already a point of local minimum. Descent method - algorithm overview Let x ∈ Df . -

Calculus Lab 4—Difference Quotients and Derivatives (Edited from U. Of

Calculus Lab 4—Difference Quotients and Derivatives (edited from U. of Alberta) Objective: To compute difference quotients and derivatives of expressions and functions. Recall Plotting Commands: plot({expr1,expr2},x=a..b); Plots two Maple expressions on one set of axes. plot({f,g},a..b); Plots two Maple functions on one set of axes. plot({f(x),g(x)},x=a..b); This allows us to plot the Maple functions f and g using the form of plot() command appropriate to Maple expressions. If f and g are Maple functions, then f(x) and g(x) are the corresponding Maple expressions. The output of this plot() command is precisely the same as that of the preceding (function version) plot() command. 1. We begin by using Maple to compute difference quotients and, from them, derivatives. Try the following sequence of commands: 1 f:=x->1/(x^2-2*x+2); This defines the function f (x) = . x 2 − 2x + 2 (f(2+h)-f(2))/h; This is the difference quotient of f at the point x = 2. simplify(%); Simplifies the last expression. limit(%,h=0); This gives the derivative of f at the point where x = 2. Exercise 1: Find the difference quotient and derivative of this function at a general point x (hint: make a simple modification of the above steps). This f (x + h) − f (x) means find and f’(x). Record your answers below. h Use this to evaluate the derivative at the points x = -1 and x = 4. (It may help to remember the subs() command here; for example, subs(x=1,e1); means substitute x = 1 into the expression e1). -

3.2 the Derivative As a Function 201

SECT ION 3.2 The Derivative as a Function 201 SOLUTION Figure (A) satisfies the inequality f .a h/ f .a h/ f .a h/ f .a/ C C 2h h since in this graph the symmetric difference quotient has a larger negative slope than the ordinary right difference quotient. [In figure (B), the symmetric difference quotient has a larger positive slope than the ordinary right difference quotient and therefore does not satisfy the stated inequality.] 75. Show that if f .x/ is a quadratic polynomial, then the SDQ at x a (for any h 0) is equal to f 0.a/ . Explain the graphical meaning of this result. D ¤ SOLUTION Let f .x/ px 2 qx r be a quadratic polynomial. We compute the SDQ at x a. D C C D f .a h/ f .a h/ p.a h/ 2 q.a h/ r .p.a h/ 2 q.a h/ r/ C C C C C C C 2h D 2h pa2 2pah ph 2 qa qh r pa 2 2pah ph 2 qa qh r C C C C C C C D 2h 4pah 2qh 2h.2pa q/ C C 2pa q D 2h D 2h D C Since this doesn’t depend on h, the limit, which is equal to f 0.a/ , is also 2pa q. Graphically, this result tells us that the secant line to a parabola passing through points chosen symmetrically about x a is alwaysC parallel to the tangent line at x a. D D 76. Let f .x/ x 2. -

CHAPTER 3: Derivatives

CHAPTER 3: Derivatives 3.1: Derivatives, Tangent Lines, and Rates of Change 3.2: Derivative Functions and Differentiability 3.3: Techniques of Differentiation 3.4: Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions 3.5: Differentials and Linearization of Functions 3.6: Chain Rule 3.7: Implicit Differentiation 3.8: Related Rates • Derivatives represent slopes of tangent lines and rates of change (such as velocity). • In this chapter, we will define derivatives and derivative functions using limits. • We will develop short cut techniques for finding derivatives. • Tangent lines correspond to local linear approximations of functions. • Implicit differentiation is a technique used in applied related rates problems. (Section 3.1: Derivatives, Tangent Lines, and Rates of Change) 3.1.1 SECTION 3.1: DERIVATIVES, TANGENT LINES, AND RATES OF CHANGE LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Relate difference quotients to slopes of secant lines and average rates of change. • Know, understand, and apply the Limit Definition of the Derivative at a Point. • Relate derivatives to slopes of tangent lines and instantaneous rates of change. • Relate opposite reciprocals of derivatives to slopes of normal lines. PART A: SECANT LINES • For now, assume that f is a polynomial function of x. (We will relax this assumption in Part B.) Assume that a is a constant. • Temporarily fix an arbitrary real value of x. (By “arbitrary,” we mean that any real value will do). Later, instead of thinking of x as a fixed (or single) value, we will think of it as a “moving” or “varying” variable that can take on different values. The secant line to the graph of f on the interval []a, x , where a < x , is the line that passes through the points a, fa and x, fx. -

Differentiation

CHAPTER 3 Differentiation 3.1 Definition of the Derivative Preliminary Questions 1. What are the two ways of writing the difference quotient? 2. Explain in words what the difference quotient represents. In Questions 3–5, f (x) is an arbitrary function. 3. What does the following quantity represent in terms of the graph of f (x)? f (8) − f (3) 8 − 3 4. For which value of x is f (x) − f (3) f (7) − f (3) = ? x − 3 4 5. For which value of h is f (2 + h) − f (2) f (4) − f (2) = ? h 4 − 2 6. To which derivative is the quantity ( π + . ) − tan 4 00001 1 .00001 a good approximation? 7. What is the equation of the tangent line to the graph at x = 3 of a function f (x) such that f (3) = 5and f (3) = 2? In Questions 8–10, let f (x) = x 2. 1 2 Chapter 3 Differentiation 8. The expression f (7) − f (5) 7 − 5 is the slope of the secant line through two points P and Q on the graph of f (x).Whatare the coordinates of P and Q? 9. For which value of h is the expression f (5 + h) − f (5) h equal to the slope of the secant line between the points P and Q in Question 8? 10. For which value of h is the expression f (3 + h) − f (3) h equal to the slope of the secant line between the points (3, 9) and (5, 25) on the graph of f (x)? Exercises 1. -

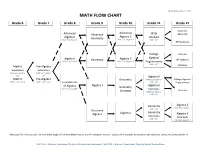

Math Flow Chart

Updated November 12, 2014 MATH FLOW CHART Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Grade 9 Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 Calculus Advanced Advanced Advanced Math AB or BC Algebra II Algebra I Geometry Analysis MAP GLA-Grade 8 MAP EOC-Algebra I MAP - ACT AP Statistics College Calculus Algebra/ Algebra I Geometry Algebra II AP Statistics MAP GLA-Grade 8 MAP EOC-Algebra I Trigonometry MAP - ACT Math 6 Pre-Algebra Statistics Extension Extension MAP GLA-Grade 6 MAP GLA-Grade 7 or or Algebra II Math 6 Pre-Algebra Geometry MAP EOC-Algebra I College Algebra/ MAP GLA-Grade 6 MAP GLA-Grade 7 MAP - ACT Foundations Trigonometry of Algebra Algebra I Algebra II Geometry MAP GLA-Grade 8 Concepts Statistics Concepts MAP EOC-Algebra I MAP - ACT Geometry Algebra II MAP EOC-Algebra I MAP - ACT Discovery Geometry Algebra Algebra I Algebra II Concepts Concepts MAP - ACT MAP EOC-Algebra I Additional Full Year Courses: General Math, Applied Technical Mathematics, and AP Computer Science. Calculus III is available for students who complete Calculus BC before grade 12. MAP GLA – Missouri Assessment Program Grade Level Assessment; MAP EOC – Missouri Assessment Program End-of-Course Exam Mathematics Objectives Calculus Mathematical Practices 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. 2. Reason abstractly and quantitatively. 3. Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. 4. Model with mathematics. 5. Use appropriate tools strategically. 6. Attend to precision. 7. Look for and make use of structure. 8. Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. Linear and Nonlinear Functions • Write equations of linear and nonlinear functions in various formats. -

Advanced Placement Calculus Advanced Placement Physics

AP Calc/Phys ADVANCED PLACEMENT CALCULUS ADVANCED PLACEMENT PHYSICS DESCRIPTION In this integrated course students will be enrolled in both AP Calculus and AP Physics. Throughout the year, topics will be covered in one subject that will supplement, reinforce, enhance, introduce, build on and extend topics in the other. Some tests will be combined, as will the exams, and some of the classes will be team taught. Calculus instruction is typically demanding and covers the topics included in the nationally approved Advanced Placement curriculum. Topics include the slope of a curve, derivatives of algebraic and transcendental functions, properties of limits, the rate of change of a function, optimization problems, Rolles and Mean Value Theorems, integration, the trapezoidal and Simpson's Rules, parametric equations and the use of scientific calculators. Physics instruction provides a systematic treatment of all of the topics required and recommended in the national AP curriculum as preparation for the AP "C" exam, specifically the mechanics part. The course is calculus based, and emphasizes not only the development of problem solving skills but also critical thinking skills. The course focuses on mechanics (statics, dynamics, momentum energy, etc.); electricity and magnetism; thermodynamics; wave phenomena (primarily electromagnetic waves); geometric optics; and, if time permits, relativity, modern and nuclear physics. I. Functions, Graphs and Limits A. Analysis of graphs. B. Limits of functions, including one-sided limits 1. Calculating limits using algebra. 2. Estimating limits from graphs or tables of data. C. Asymptotic and unbounded behavior. 1. Understanding asymptotes in terms of graphical behavior. 2. Describing asymptotic behavior in terms of limits involving infinity. -

Numerical Differentiation

Chapter 11 Numerical Differentiation Differentiation is a basic mathematical operation with a wide range of applica- tions in many areas of science. It is therefore important to have good meth- ods to compute and manipulate derivatives. You probably learnt the basic rules of differentiation in school — symbolic methods suitable for pencil-and-paper calculations. Such methods are of limited value on computers since the most common programming environments do not have support for symbolic com- putations. Another complication is the fact that in many practical applications a func- tion is only known at a few isolated points. For example, we may measure the position of a car every minute via a GPS (Global Positioning System) unit, and we want to compute its speed. When the position is known at all times (as a mathematical function), we can find the speed by differentiation. But when the position is only known at isolated times, this is not possible. The solution is to use approximate methods of differentiation. In our con- text, these are going to be numerical methods. We are going to present several such methods, but more importantly, we are going to present a general strategy for deriving numerical differentiation methods. In this way you will not only have a number of methods available to you, but you will also be able to develop new methods, tailored to special situations that you may encounter. The basic strategy for deriving numerical differentiation methods is to evalu- ate a function at a few points, find the polynomial that interpolates the function at these points, and use the derivative of this polynomial as an approximation to the derivative of the function. -

Unit #4 - Inverse Trig, Interpreting Derivatives, Newton’S Method

Unit #4 - Inverse Trig, Interpreting Derivatives, Newton's Method Some problems and solutions selected or adapted from Hughes-Hallett Calculus. Computing Inverse Trig Derivatives 1. Starting with the inverse property that 3. Starting with the inverse property that sin(arcsin(x)) = x, find the derivative of arcsin(x). tan(arctan(x)) = x, find the derivative of arctan(x). You will need to use the trig identity You will need to use the trig identity 2 2 sin2(x) + cos2(x) = 1. sin (x)+cos (x) = 1, or its related form, dividing each term by cos2(x), 2. Starting with the inverse property that tan2(x) + 1 = sec2(x) cos(arccos(x)) = x, find the derivative of arccos(x). You will need to use the trig identity sin2(x) + cos2(x) = 1. Interpreting Derivatives 4. The graph of y = x3 − 9x2 − 16x + 1 has a slope of 5 At what rate was the population changing on January at two points. Find the coordinates of the points. 1st, 2010, in units of people/year? 5. Determine coefficients a and b such that p(x) = x2 + 10. The value of an automobile can be approximated by ax + b satisfies p(1) = 3 and p0(1) = 1. the function V (t) = 25(0:85)t; 6. A ball is thrown up in the air, and its height over time is given by where t is in years from the date of purchase, and V (t) f(t) = −4:9t2 + 25t + 3 is its value, in thousands of dollars. where t is in seconds and f(t) is in meters. -

Chapter 13 Answers A.69 Chapter 13 Answers 13.1 Vectors in the Plane 31

Chapter 13 Answers A.69 Chapter 13 Answers 13.1 Vectors in the Plane 31. y 1. (4,9) 3. (-15, 3) 3 5. Y = 1 7. No solution 9. No solution 11. No solution 13. a = 4, b = - I 15. a = 0, b = I 17. (XI, YI) + (0,0) = (XI + 0, YI + 0) = (XI' YI) 3 x 19. [(XI' YI) + (X2, Yz)] + (x3' YJ) = (XI + X2 + X3, YI + Yz + Y3) = (XI' YI) + [(X2, Yz) + (x3, Y3)] 21. a(b(x, Y» = a(bx, by) = (abx, aby) = ab(x, y) 33. y 23. y 2 • • • • •• • • • • •• x x • •• • • • 4 • • • • • • 35. 25. (a) k(l,3) + 1(2,0) = m(1, 2) (b) k + 21 = m and 3k + 0 = 2m x (c) k = 4,1 = 1 and m = 6; i.e. 4S03 + S2 = 6S02 27. (a) d (b) e 29. (a) c + d = (6,2) -6 y 37. (a) 2 .r Q x 3 6 vAw Pl....-).R u 234 x (b) -2e+a=(-1,0) (b) v=(l,2); w=(1, -2); u=(-2,0) (c) 0 y 39. (a) y -2e+a x x (b) (0, I) A.70 Chapter 13 Answers (c) (0,5/2) 9. (d) (0, -2) x 11. w -2 (e) (I, y) (f) v=(O,y) 41. (a) Yes (c) Eliminate rand s. w (b) v = -(s/r)w (d) Solve linear equations. 13. - i + 2j + 3k 15. 7i + 2j + 3k 13.2 Vectors in Space 17. i - k 19. i - j + k 21. i + 4j, B ~ 0.24 radians east of north 1. 23. -

2.1 the Derivative and the Tangent Line Problem

96 Chapter 2 Differentiation 2.1 The Derivative and the Tangent Line Problem Find the slope of the tangent line to a curve at a point. Use the limit definition to find the derivative of a function. Understand the relationship between differentiability and continuity. The Tangent Line Problem Calculus grew out of four major problems that European mathematicians were working on during the seventeenth century. 1. The tangent line problem (Section 1.1 and this section) 2. The velocity and acceleration problem (Sections 2.2 and 2.3) 3. The minimum and maximum problem (Section 3.1) 4. The area problem (Sections 1.1 and 4.2) Each problem involves the notion of a limit, and calculus can be introduced with any of the four problems. A brief introduction to the tangent line problem is given in Section 1.1. Although partial solutions to this problem were given by Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665), René Descartes (1596–1650), Christian Huygens (1629–1695), and Isaac Barrow (1630–1677), credit for the first general solution is usually given to Isaac Newton (1642–1727) and Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716). Newton’s work on this problem ISAAC NEWTON (1642–1727) stemmed from his interest in optics and light refraction. In addition to his work in calculus, What does it mean to say that a line is Newton made revolutionary y contributions to physics, including tangent to a curve at a point? For a circle, the the Law of Universal Gravitation tangent line at a point P is the line that is and his three laws of motion.