Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

TCEC15: the 15Th Top Chess Engine Championship

TCEC15: the 15th Top Chess Engine Championship Guy Haworth1 and Nelson Hernandez Reading, UK and Maryland, USA TCEC Season 15 started on March 5th 2019 with a more liberal Division 4 featuring several engines in their first TCEC season. At the top end, interest would centre on whether the recent entries, ETHEREAL, KOMODO MCTS and LEELA CHESS ZERO would again improve their already impressive performances. Fig. 1 and Table 1 provide the logos and details on the enlarged field of 44 engines. DP D1 D2 D3 D4 Fig. 1. Logos for the TCEC 15 engines (CPW, 2019) as in their original divisions. There were a few nudges to the rules. In the event of network breaks, if both engines were in the 7-man and/or TCEC win (or draw) zone, the game was adjudicated as a win (or draw). Otherwise, TCEC resumed games with extra initialisation time rather than restart them. The common platform for TCEC15, as for TCEC14, consisted of two computers. One was the estab- lished, formidable 44-core server of TCEC11-14 (Intel, 2017) with 64GiB of DDR4 ECC RAM and a Crucial CT250M500 240 GB SSD for the EGTs. The ‘GPU server’, upgraded to a Quad Core i5 3570k with 32GiB DDR3 RAM, sported Nvidia (2018) GeForce RTX 2080 Ti and 2080 GPUs. 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] Table 1. The TCEC15 engines (CPW, 2019), details, authors and progress. Engine Initial proto- Hash Countr Final # thr. EGTs Authors ab Name Version ELO Div. col Kb y Codes Div. 01 AS AllieStein v0.1-n4 2557 4b 3 uci 7,168 — Adam Treat and Mark Jordan US ↗↗ ↗↗P 02 An Andscacs 0.95123 3469 1 43 uci 8,192 — Daniel José Queraltó AD →1 03 Ar Arasan TCEC15 3290 3 43 uci 16,384 Syz. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

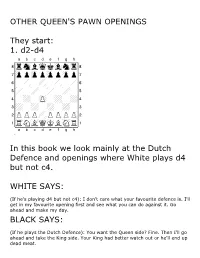

OTHER QUEEN's PAWN OPENINGS They Start: 1. D2-D4 XABCDEFGH

OTHER QUEEN'S PAWN OPENINGS They start: 1. d2-d4 XABCDEFGH 8rsnlwqkvlntr( 7zppzppzppzpp' 6-+-+-+-+& 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-zP-+-+$ 3+-+-+-+-# 2PzPP+PzPPzP" 1tRNvLQmKLsNR! Xabcdefgh In this book we look mainly at the Dutch Defence and openings where White plays d4 but not c4. WHITE SAYS: (If he's playing d4 but not c4): I don't care what your favourite defence is. I'll get in my favourite opening first and see what you can do against it. Go ahead and make my day. BLACK SAYS: (If he plays the Dutch Defence): You want the Queen side? Fine. Then I'll go ahead and take the King side. Your King had better watch out or he'll end up dead meat. XABCDEFGHY 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zppzp-vl-zpp' The Classical Dutch. 6-+-zppsn-+& Black's plans are to play e6-e5 or to 5+-+-+p+-% attack on the King side with moves like 4-+-+-+-+$ Qd8-e8, Qe8-h5, g7-g5, g5-g4. White 3+-+-+-+-# will try to play e2-e4, open the e-file 2-+-+-+-+" and attack Black's weak e-pawn. For this reason he will usually develop his 1+-+-+-+-! King's Bishop on g2. xabcdefghy xABCDEFGH 8rsnlwq-trk+( 7zpp+-+-zpp' The Dutch Stonewall. 6-+pvlpsn-+& Black gains space but leaves a 5+-+p+p+-% weakness on e5. He can either play for 4-+-+-+-+$ a King side attack, again with Qd8-e8, 3+-+-+-+-# Qe8-h5, g7-g5, or play in the centre 2-+-+-+-+" with b7-b6 and c6-c5. White will aim to control or occupy the e5 square with a 1+-+-+-+-! Knight while trying to break with e2-e4. -

Npcc Fall Open Turns

The PENNSWOODPUSHER November 2003 A Quarterly Publication of the Pennsylvania State Chess Federation "The Ideal Socialism" Bill Ruth, the Ruth Opening, and Bill Ruth − Isidor Turover [D00] Correspondence Chess Philadelphia−Washington telephone match, November 25, 1922 1.d4 ¤f6 2.¥g5 In recent years the opening variations 1.d4 d5 2.Bg5 and 1.d4 Nf6 2.Bg5, commonly known as the Trompowsky opening after the XIIIIIIIIY Brazilian chess master Octavio Siqueiro F. Trompowsky, have become 9rsnlwqkvl-tr0 popular with many chessplayers at all levels of playing ability. The chief proponent of the Trompowsky, or the "Tromp" as fans call it, 9zppzppzppzpp0 during the past decade and a half has been the talented British Grandmaster Julian Hodgson, who uses it as a mainstay of his opening 9-+-+-sn-+0 repertoire. 9+-+-+-vL-0 Grandmaster Joe Gallagher, writing in his book The Trompowsky (The Chess Press, 1998) suggests renaming the Trompowsky opening to 9-+-zP-+-+0 reflect Hodgson's role in promoting its use at the highest level, 9+-+-+-+-0 although even Gallagher admits "the Hodgson-Trompowsky Attack is such a mouthful that I fear it will never happen." What Gallagher and 9PzPP+PzPPzP0 others are overlooking is that the opening has another name for another popularizer, at least in the United States. The talented and free-thinking 9tRN+QmKLsNR0 Philadelphia chess master and Pennsylvania State Chess Champion William Allan Ruth (1886-1975) first began surprising opponents with xiiiiiiiiy 2...d5 3.¤d2 c6 4.¤gf3 £b6 5.¥xf6 exf6 6.b3 ¥b4 7.e3 ¥f5 the second move Queen's Bishop sortie in the early 1920's. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS.. -

Catastrophes & Tactics in the Chess Opening

Winning Quickly at Chess: Catastrophes & Tactics in the Chess Opening – Selected Brilliancies from Volumes 1-9 Chess Tactics, Brilliancies & Blunders in the Chess Opening by Carsten Hansen 2018 CarstenChess Catastrophes & Tactics in the Chess Opening: Selected Brilliancies Winning Quickly at Chess: Catastrophes & Tactics in the Chess Opening – Selected Brilliancies from Volumes 1-9 Copyright © 2018 by Carsten Hansen All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in the United States of America First Printing, 2018 ISBN (print edition): 978-1-980-559429 CarstenChess 207 Harbor Place Bayonne, NJ 07002 www.WinningQuicklyatChess.com 1 Catastrophes & Tactics in the Chess Opening: Selected Brilliancies Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 5 VOLUME 1 ...................................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1.1 The King’s Indian Defense ......................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1.2 The Grünfeld Indian Defense ................................................................. 10 CHAPTER -

Download the Latest Catalogue

TABLE OF CONTENTS To view a particular category within the catalogue please click on the headings below 1. Antiquarian 2. Reference; Encyclopaedias, & History 3. Tournaments 4. Game collections of specific players 5. Game Collections – General 6. Endings 7. Problems, Studies & “Puzzles” 8. Instructional 9. Magazines & Yearbooks 10. Chess-based literature 11. Children & Junior Beginners 12. Openings Keverel Chess Books July – January. Terms & Abbreviations The condition of a book is estimated on the following scale. Each letter can be finessed by a + or - giving 12 possible levels. The judgement will be subjective, of course, but based on decades of experience. F = Fine or nearly new // VG = very good // G = showing acceptable signs of wear. P = Poor, structural damage (loose covers, torn pages, heavy marginalia etc.) but still providing much of interest. AN = Algebraic Notation in which, from White’s point of view, columns are called a – h and ranks are numbered 1-8 (as opposed to the old descriptive system). Figurine, in which piece names are replaced by pictograms, is now almost universal in modern books as it overcomes the language problem. In this case AN may be assumed. pp = number of pages in the book.// ed = edition // insc = inscription – e.g. a previous owner’s name on the front endpaper. o/w = otherwise. dw = Dust wrapper It may be assumed that any book published in Russia will be in the Russian language, (Cyrillic) or an Argentinian book will be in Spanish etc. Anything contrary to that will be mentioned. PB = paperback. SB = softback i.e. a flexible cover that cannot be torn easily. -

First Steps : the Modern

First Steps : the Modern CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 The Pseudo-Dragon and Pseudo-Lopez 18 2 The Classical Variation 45 3 The Jump to Nowhere 60 4 The Íc4 Cro-Magnon Lines 72 5 Fianchetto Lines 86 6 The Coward’s Variation 99 7 The Austrian Attack 114 8 The Dzindzi-Indian 136 9 The Averbakh Variation 158 10 Other d4 and c4 Lines 175 11 English Opening Set-ups 208 12 Anti-Queen’s Pawn Lines and Everything Else 227 Index of Variations 251 Index of Complete Games 256 Introduction If your writer is the Dr. -

Openings.Pdf

OPEN GAMES They start: 1. e2-e4 e7-e5 XABCDEFGH 8rsnlwqkvlntr( 7zppzpp+pzpp' 6-+-+-+-+& 5+-+-zp-+-% 4-+-+P+-+$ 3+-+-+-+-# 2PzPPzP-zPPzP" 1tRNvLQmKLsNR! Xabcdefgh WHITE SAYS: You're expecting the Ruy Lopez? Tough. I'm going to play my favourite opening and see what you know about it. It could be anything from a wild gambit to a quiet line. You'll soon find out. BLACK SAYS: These openings really aren't so scary. I'm well prepared: I can reach at least an equal position whichever one you choose. Go ahead and do your worst. XABCDEFGH 8rsnlwqkvlntr( 7zppzpp+pzpp' 6-+-+-+-+& 5+-+-zp-+-% 4-+-+P+-+$ 3+-+-+-+-# 2PzPPzP-zPPzP" 1tRNvLQmKLsNR! Xabcdefgh Most of these openings fall into one of three categories: 1. White plays for a central break with d4 (Scotch Game, Ponziani, most lines of Giuoco Piano and Two Knights). 2. White plays for a central break with f4 (King's Gambit, most lines of the Vienna and Bishop's Opening). 3. White plays quietly with d3 (Giuoco Pianissimo, Spanish Four Knights). We also look at some other defences for Black after 2. Ng1-f3, from safe defensive systems to sharp counter- gambits. What should Black do next? Ideas for White: Adults will expect the Ruy Lopez while juniors are more used to this sort of opening. So it's a good idea to play the Ruy Lopez against juniors, and, for example, the Giuoco Piano against adults. Most of these openings lead to open positions. Rapid, effective development and King safety are the most important factors. Don't play the Ng5 line against good opponents unless you really know what you're doing.