National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Bishops Park Have Been Named After Them

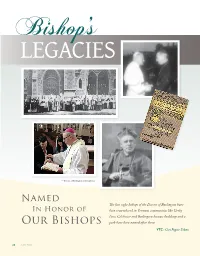

B ishop’s LEGACIES — Diocese of Burlington archive photos Named The first eight bishops of the Diocese of Burlington have In Honor of been remembered in Vermont communities like Derby Line, Colchester and Burlington because buildings and a Our Bishops park have been named after them. VTC • Cori Fugere Urban 24 FALL 2017 BURLINGTON’S BISHOPS Bishop Louis deGoesbriand Bishop John Stephen Michaud First Bishop of Burlington Second Bishop of Burlington 1853–1899 1899–1908 “the founding bishop” “the builder bishop” Bishop Louis deGoesbriand was the first bishop of the The first native-born priest ordained for the Diocese of Diocese of Burlington, which was founded in 1853. Burlington, Bishop John S. Michaud began his building When he died in 1899, he left behind a Church that initiatives in Newport, his first assignment after his had grown in number of Catholics, number of churches 1873 ordination to the priesthood. St. Mary Star of the and number of Catholic schools. By 1891, there were Sea Church was the first of many construction projects eight academies and 16 parochial schools in the he would oversee in his life. In 1879, Bishop deGoes- Diocese with seven congregations of women religious briand summoned him back to Burlington to oversee to staff them. Five priests had awaited his arrival, and the building of St. Joseph’s Providence Orphan Asylum. the number of Vermont priests grew to 52 in 1892 Later, he oversaw the building of St. Francis de Sales thanks to his efforts to foster vocations in Vermont and Church in Bennington before being named coadjutor recruit priests from France, Canada and Ireland. -

El Opus Dei En Estados Unidos (1949-1957). Cronología, Geografía, Demografía Y Dimensiones Institucionales De Unos Inicios Federico M

STUDIA ET DOCUMENTA RIvISTA DEll’ISTITUTO STORICO San JosemaríA Escrivá VOL. 13 – 2019 ISTITUTO STORICO SAN JOSEMARíA ESCRIvá – ROMA Sommario El Opus Dei en el continente americano Presentación Fernando Crovetto ....................................... 9 El Opus Dei en Estados Unidos (1949-1957). Cronología, geografía, demografía y dimensiones institucionales de unos inicios Federico M. Requena ...................................... 13 El centro de la Carrera cuarta. El primer centro del Opus Dei en Colombia (1952-1953) Manuel Pareja ........................................... 95 El Instituto de Capacitación Integral en Estudios Domésticos (ICIED): génesis y evolución de una escuela dirigida a promover la dignidad de la mujer y el valor del servicio Ana María Sanguineti .................................... 127 Studi e note The Beginnings of Opus Dei in Ireland Leading to the Establishment of its First Corporate Apostolate, Nullamore University Residence, Dublin in 1954 Chris Noonan ........................................... 177 Los primeros pasos de la “obra de San Gabriel” (1928-1950) Alfredo Méndiz ......................................... 243 Las primeras agregadas del Opus Dei (1949-1955). Una aproximación prosopográfica María Hernández Sampelayo Matos – María Eugenia Ossandón Widow ... 271 José Orlandis (1918-2010): biographie et historiographie Martin Aurell .......................................... 325 ISSN 1970-4879 SetD 13 (2019) 3 Documenti Una larga amistad. Correspondencia entre san Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer y Mons. Manuel -

Studia Et Documenta

El Opus Dei en Estados Unidos (1949-1957). Cronología, geografía, demografía y dimensiones institucionales de unos inicios* FEDERICO M. REQUENA Abstract: Entre febrero de 1949 y otoño de 1957, el Opus Dei en Estados Uni- dos pasó de ser un pequeño grupo de cinco pioneros, establecidos en Chicago, a contar con unos ciento cincuenta miembros y centros en seis ciudades del Midwest y de la Costa Este. El artículo se centra en el trabajo apostólico de los hombres del Opus Dei y se propone establecer la cronología, la geografía y la demografía, y abordar algunas dimensiones institucionales de estos comien- zos. Se distinguen tres etapas: los inicios (1949-1953), la primera madurez (1953-1955) y el crecimiento que dio paso a la división en dos circunscripcio- nes (1955-1957). Keywords: Opus Dei – José Luis Múzquiz – José María Escrivá de Balaguer – Estados Unidos – 1949-1957 Opus Dei in the United States (1949-1957) . Chronology, Geography, Demography and Institutional Dimensions of the Early Days: Between February 1949 and the fall of 1957, Opus Dei in the United States went from a small group of five pioneers, based in Chicago, to one hundred and fifty members with centers in six cities in the Midwest and on the East Coast. This article focuses on the apostolic work of the men of Opus Dei and endeavors to establish the timeline, geography, and the demographics of this period. The article also seeks to address some of the institutional dimensions of these * Quedan fuera del presente estudio los inicios protagonizados por las mujeres del Opus Dei, que están siendo abordados por Inmaculada Alva, investigadora de la Universidad de Navarra. -

El Opus Dei En Estados Unidos (1949-1957)

STUDIA ET DOCUMENTA RIvISTA DEll’ISTITUTO STORICO San JosemaríA Escrivá VOL. 13 – 2019 ISTITUTO STORICO SAN JOSEMARíA ESCRIvá – ROMA Sommario El Opus Dei en el continente americano Presentación Fernando Crovetto ....................................... 9 El Opus Dei en Estados Unidos (1949-1957). Cronología, geografía, demografía y dimensiones institucionales de unos inicios Federico M. Requena ...................................... 13 El centro de la Carrera cuarta. El primer centro del Opus Dei en Colombia (1952-1953) Manuel Pareja ........................................... 95 El Instituto de Capacitación Integral en Estudios Domésticos (ICIED): génesis y evolución de una escuela dirigida a promover la dignidad de la mujer y el valor del servicio Ana María Sanguineti .................................... 127 Studi e note The Beginnings of Opus Dei in Ireland Leading to the Establishment of its First Corporate Apostolate, Nullamore University Residence, Dublin in 1954 Chris Noonan ........................................... 177 Los primeros pasos de la “obra de San Gabriel” (1928-1950) Alfredo Méndiz ......................................... 243 Las primeras agregadas del Opus Dei (1949-1955). Una aproximación prosopográfica María Hernández Sampelayo Matos – María Eugenia Ossandón Widow ... 271 José Orlandis (1918-2010): biographie et historiographie Martin Aurell .......................................... 325 ISSN 1970-4879 SetD 13 (2019) 3 Documenti Una larga amistad. Correspondencia entre san Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer y Mons. Manuel