Let's Start at the Top and Work Our Way Down, North to South, One Square to Another, One World to Another

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: a Tour of 1950'S Philadelphia Skid

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: A Tour of 1950’s Philadelphia Skid Row Stephen Metraux [email protected] Article for hiddencityphila.org March 2017 An approach to Philadelphia not soon forgotten is on the beautiful [Benjamin Franklin] Bridge high over the river and the city, followed by Franklin Square – also known as “Bum’s Park.” When a traveler sees a tree-filled square with hundreds of men reclining on park benches or lined up for soup and salvation across the street then he has arrived in Philadelphia. The Health and Welfare Council (HWC) opened their 1952 report “What About Philadelphia’s Skid Row?” with this vignette of a motorist’s first impression of Philadelphia. Coming off the bridge from New Jersey, cars would land on Vine Street at 6th Street, with Franklin Square taking up the southern side of the block and the Sunday Breakfast Mission sitting on the northwest corner. This was the gateway to Skid Row, and, for the next three blocks, Vine Street was its main drag. What follows continues the Skid Row tour that the HWC report started 65 years ago by reconstructing this segment of 1950s Vine Street that now lies buried under its namesake expressway. The HWC report directed Philadelphia’s attention to its Skid Row. Generically, skid row denoted an area, present in larger mid-twentieth century American cities, that originated as a pre-Depression era district of itinerant and near indigent workingmen. As this population aged and dwindled after World War II, these areas retained signature amenities such as cheap hotels, religious missions, and bars, all ensconced by seediness and decay. -

William Poole - the Real "Bill the Butcher"

William Poole - The Real "Bill The Butcher" William Poole was a Nativist enforcer of The Native American Party, also known as The Know Nothing Party, which was a faction of the American Republican Party. The Know Nothing was a movement created by Nativists whom believed that the overwhelming immigration of German and Irish Catholic immigrants were a threat to republican values and controlled by the Pope in Rome. They were dubbed the Know Nothings by outsiders of their semi-secret organization. This had nothing to do with them knowing anything. It had to do with their reply when asked of the organization's activities, often stating, "I know nothing." Bill the Butcher was a leader of The Bowery Boys and known for his skills as being a good bare knuckle boxer. Poole's trade was that of a butcher, and was infuriated when many butchering licenses were being handed out to Irish immigrants. William Poole was born in Sussex County, New Jersey to parents of English protestant descent. His family moved to New York City in 1832 to open a butcher shop in Washington Market, Manhattan. Bill Poole trained in his father's trade and eventually took over the family store. In the 1840s, he worked with the Howard (Red Rover) Volunteer Fire Engine Company #34, Hudson & Christopher Street. Uunlike in the movie, William "The Butcher" Poole was shot in real life. However, he was shot at Stanwix Hall, a bar on Broadway near Prince. William Poole did not die in a glorious street battle against his Irish enemies. Instead, he died from the gun wound at his home on Christopher Street. -

Youth Gangs: Legislative Issues in the 109Th Congress

Order Code RL33400 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Youth Gangs: Legislative Issues in the 109th Congress April 21, 2006 Celinda Franco Specialist in Social Legislation Domestic Social Policy Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Youth Gangs: Legislative Issues in the 109th Congress Summary Gang activity and related violence threaten public order in a diverse range of communities in the United States today. Congress has long recognized that this problem affects a number of issues of federal concern, and federal legislation has been introduced in the 109th Congress to address the subject. Youth gangs have been an endemic feature of American urban life. They are well attested as early as the 18th century and have been a recurrent subject of concern since then. Contemporary views of the problem have been formed against the background of a significant adverse secular trend in gang activity during the last four decades. In particular, the rapid growth of gang membership, geographical dispersion, and criminal involvement during the violent crime epidemic — associated with the emergence of the crack cocaine market during the mid-1980s to the early 1990s — have intensified current concerns. The experience of those years continues to mark both patterns of gang activity and public policy responses toward them. Reports about the increased activity and recent migration of a violent California- based gang, the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), have heightened concerns about gangs in certain areas of the country. Policy development and implementation in this area are bedeviled by discrepant uses of the term “gang” and the absence of uniform standards of statistical reporting. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

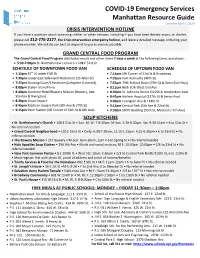

COVID-19 Emergency Services Manhattan Resource Guide

COVID-19 Emergency Services Manhattan Resource Guide Updated April 6, 2020 CRISIS INTERVENTION HOTLINE If you have a question about accessing shelter or other services, including if you have been denied access to shelter, please call 212-776-2177, the Crisis Intervention emergency hotline, and leave a detailed message, including your phone number. We will do our best to respond to you as soon as possible. GRAND CENTRAL FOOD PROGRAM The Grand Central Food Program distributes meals and other items 7 days a week at the following times and places: 5:30-7:00pm St. Bartholomew's Church • 108 E 51st St SCHEDULE OF DOWNTOWN FOOD VAN SCHEDULE OF UPTOWN FOOD VAN th 7:15pm 35 St under FDR Dr 7:15pm SW Corner of 51st St & Broadway 7:30pm Lower East Side Harm Reduction (25 Allen St) 7:35pm Port Authority (40th St) 7:45pm Housing Court/Chinatown (Lafayette /Leonard) 7:55pm 79th St Boat Basin (79th St & West Side Hwy) 8:00pm Staten Island Ferry 8:15pm 86th St & West End Ave 8:20pm Sunshine Hotel/Bowery Mission (Bowery, btw 8:30pm St. John the Divine (112th & Amsterdam Ave) Stanton & Rivington) 8:45pm Harlem Hospital (137th St & Lenox Ave) 8:30pm Union Square 9:00pm Lexington Ave & 124th St 8:45pm Madison Square Park (5th Ave & 27th St) 9:15pm Central Park (5th Ave & 72nd St) 9:15pm Penn Station (NE Corner of 34th St & 8th Ave) 9:30pm SONY Building (55th St, Madison / 5th Ave) SOUP KITCHENS • St. Bartholomew's Church • 108 E 51st St • Sun, M, W: 7-8:30am; M-Sun: 5:30-6:30pm; Sat: 9:30-11am • 6 to 51st St • No referral needed • Grand -

[email protected] Sent

Archived: Monday, August 17, 2020 11:18:30 AM From: [email protected] Sent: Sunday, August 16, 2020 9:08:08 PM To: agenda comments; Mark Apolinar Subject: [EXTERNAL] Agenda Comments Response requested: Yes Sensitivity: Normal A new entry to a form/survey has been submitted. Form Name: Comment on Agenda Items Date & Time: 08/16/2020 9:08 pm Response #: 635 Submitter ID: 38307 IP address: 50.46.194.37 Time to complete: 6 min. , 20 sec. Survey Details: Answers Only Page 1 1. Margaret Willson 2. Shoreline 3. (○) Richmond Beach 4. [email protected] 5. 08/17/2020 6. 9(a) 7. Dear Shoreline City Council, I am writing about the low barrier Navigation Center being proposed for the former site of Arden Rehab on Aurora Avenue. I read the "Shoreline Area News" notes from your August 10 meeting, and I saw that many of you have embraced a "Housing First" approach to addressing homelessness. I've always been skeptical of the Housing First philosophy, because homelessness, rather than being a person's primarily problem, is usually a symptom of a deeper problem or problems. Fortuituously, I just this past week learned of a brand new report on Housing First by Seattle's own Christopher Rufo, who is a Visiting Fellow for Domestic Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation. The report presents abundant evidence that Housing First works pretty well at keeping a roof over people's heads, but not so well at healing them and helping them turn their lives around. What does work to actually help people is "Treatment First". -

Riis's How the Other Half Lives

How the Other Half Lives http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES The Hypertext Edition STUDIES AMONG THE TENEMENTS OF NEW YORK BY JACOB A. RIIS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS CHIEFLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR Contents NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1890 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM Contents http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/contents.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES CONTENTS. About the Hypertext Edition XII. The Bohemians--Tenement-House Cigarmaking Title Page XIII. The Color Line in New York Preface XIV. The Common Herd List of Illustrations XV. The Problem of the Children Introduction XVI. Waifs of the City's Slums I. Genesis of the Tenements XVII. The Street Arab II. The Awakening XVIII. The Reign of Rum III. The Mixed Crowd XIX. The Harvest of Tare IV. The Down Town Back-Alleys XX. The Working Girls of New York V. The Italian in New York XXI. Pauperism in the Tenements VI. The Bend XXII. The Wrecks and the Waste VII. A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives XXIII. The Man with the Knife VIII.The Cheap Lodging-Houses XXIV. What Has Been Done IX. Chinatown XXV. How the Case Stands X. Jewtown Appendix XI. The Sweaters of Jewtown 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM List of Illustrations http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/illustrations.html LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Gotham Court A Black-and-Tan Dive in "Africa" Hell's Kitchen and Sebastopol The Open Door Tenement of 1863, for Twelve Families on Each Flat Bird's Eye View of an East Side Tenement Block Tenement of the Old Style. -

Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416

Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416 Prepared for: Submitted to: City of New York - Department of Parks and Recreation A.A.H. Construction Corporation Olmstead Center; Queens, New York 18-55 42nd Street Astoria, New York 11105-1025 and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Peebles Island, New York Prepared by: Alyssa Loorya, M.A., R.P.A., Principal Investigator and Christopher Ricciardi, Ph.D., R.P.A. for: Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, Incorporated October 2005 Columbus Park; New York, (New York County) New York – Phase 1A and Partial Monitoring Report Project Number: M015-203MA NYSOPRHP Project Number: 02PR03416 Prepared for: Submitted to: City of New York - Department of Parks and Recreation A.A.H. Construction Corporation Olmstead Center; Queens, New York 18-55 42nd Street Astoria, New York 11105-1025 and New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Peebles Island, New York Prepared by: Alyssa Loorya, M.A., R.P.A., Principal Investigator and Christopher Ricciardi, Ph.D., R.P.A. for: Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, Incorporated October 2005 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Between September 2005 and October 2005, a Phase 1A Documentary Study and a partial Phase 1B Archaeological Monitoring was undertaken at Columbus Park, Block 165, Lot 1, New York, (New York County) New York. The project area is owned by the City of New York and managed through the Department of Parks and Recreation (Parks). The Parks’ Contract Number for the project is: M015-203MA. The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation’s (NYSOPRHP) File Number for the project is: 02PR03416. -

The Bowery Series and the Transformation of Prostate Cancer, 1951–1966

This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details. From Skid Row to Main Street: The Bowery Series and the Transformation of Prostate Cancer, 1951–1966 ROBERT ARONOWITZ SUMMARY: Between 1951 and 1966, more than 1,200 homeless, alcoholic men from New York’s skid row were subjected to invasive medical procedures, including open perineal biopsy of the prostate gland. If positive for cancer, men underwent prostatectomy, surgical castration, and estrogen treatments. The Bowery series was meant to answer important questions about prostate cancer’s diagnosis, natural history, prevention, and treatment. While the Bowery series had little ultimate impact on practice, in part due to ethical problems, its means and goals were prescient. In the ensuing decades, technological tinkering catalyzed the transformation of prostate cancer attitudes and interventions in directions that the Bowery series’ promoters had anticipated. These largely forgotten set of practices are a window into how we have come to believe that the screen and radical treatment paradigm in prostate cancer is efficacious and the underlying logic of the twentieth century American quest to control cancer and our fears of cancer. KEYWORDS: cancer, prostate cancer, history of medicine, efficacy, risk, screening, bioethics 1 This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details. -

Albany County

Navigator Agency Site Locations In light of the situation surrounding the Coronavirus, please call ahead before arriving at any site location, as the location may have temporarily changed. County: Albany Lead Agency Name Healthy Capital District Initiative Subcontractor's Name N/A Enrollment Site Name Cohoes Senior Center Site Address 10 Cayuga Plaza City Cohoes NY 12047 Phone # (518) 462-7040 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Capital City Rescue Mission Free Clinic Site Address 88 Trinity Place City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Albany County Department of Health Clinic Site Address 175 Green Street City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Addiction Care Center of Albany Site Address 90 McCarty Avenue City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Trinity Center Site Address 15 Trinity Place City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish NYS Department of Health Report Date: 9/1/2021 Navigator Agency Site Locations In light of the situation surrounding the Coronavirus, please call ahead before arriving at any site location, as the location may have temporarily changed. -

Eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds Ho" It

1 9 -- THE SUN; SUNDAY, AtlGtlSTriSWi 1! eau Brummels of Gangland and the Killing They Did in Feuds ho" it v" A!. W4x 1WJ HERMAN ROSEHTHAL WHOSE K.1LLINQ- - POLICE COMMISSIOKER. EH RIGHT WHO IS IN $ MARKED T?e expressed great indignation that a KEEPING TJe GANGS SUBdECTIOK. BEGINNING-O- F crime had been committed. Ploggl .TAe stayed in. hiding for a few days whllo tho politicians who controlled the elec END FOR. tion services of the Five Points ar- ranged certain matters, and then ho Slaying of Rosenthal Marked the Be surrendered. Of courso ho pleaded e. ginning of the End for Gangs Whose "Biff" Ellison, who was sent to Sing Sing for his part In the killing of by Bill Harrington in Paul Kelly's New Grimes Had Been Covered a Brighton dive, came to the Bowery from Maryland when he was in his Crooked Politicians Some of WHERE early twenties. Ho got a Job' as ARTHUR. WOOD5P WHO PUT T5e GANGS bouncer in Pat Flynn's saloon in 34 Reformed THEY ObLUncr. Bond street, and advanced rapidly in Old Leaders Who tho estimation of gangland, because he was young and husky when he and zenship back Tanner Smith becamo as approaching tho end of his activities. hit a man that man went down and r 0 as anybody. Ho got Besides these there were numerous stayed down. That was how he got decent a citizen Murders Resulting From Rivalry Among Gangsters Were a Job as beef handler on the docks, other fights. bis nickname ho used to be always stevedore, and threatening to someone. -

New York's Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian

FRUNZA, BOGDANA SIMINA., M.S. Streetscape and Ethnicity: New York’s Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian American Ethnic Identity. (2008) Directed by Prof. Jo R. Leimenstoll. 161 pp. The current research looked at ways in which the built environment of an ethnic enclave contributes to the definition and redefinition of the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. Assuming a dynamic component of the built environment, the study advanced the idea of the streetscape as an active agent of change in the definition and redefinition of ethnic identity. Throughout a century of existence, Little Italy – New York’s most prominent Italian enclave – changed its demographics, appearance and significance; these changes resonated with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. From its beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century until the present, Little Italy’s Mulberry Street has maintained its privileged status as the core of the enclave, but changed its symbolic role radically. Over three generations of Italian immigrants, Mulberry Street changed its role from a space of trade to a space of leisure, from a place of providing to a place of consuming, and from a social arena to a tourist tract. The photographic analysis employed in this study revealed that changes in the streetscape of Mulberry Street connected with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants, from regional Southern Italian to Italian American. Moreover, the photographic evidence demonstrates the active role of the street in the permanent redefinition of