Investigating Research Integrity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedy Taken Seriously the Mafia’S Ties to a Murder

MONDAY Beauty and the Beast www.annistonstar.com/tv The series returns with an all-new episode that finds Vincent (Jay Ryan) being TVstar arrested for May 30 - June 5, 2014 murder. 8 p.m. on The CW TUESDAY Celebrity Wife Swap Rock prince Dweezil Zappa trades his mate for the spouse of a former MLB outfielder. 9 p.m. on ABC THURSDAY Elementary Watson (Lucy Liu) and Holmes launch an investigation into Comedy Taken Seriously the mafia’s ties to a murder. J.B. Smoove is the dynamic new host of NBC’s 9:01 p.m. on CBS standup comedy competition “Last Comic Standing,” airing Mondays at 7 p.m. Get the deal of a lifetime for Home Phone Service. * $ Cable ONE is #1 in customer satisfaction for home phone.* /mo Talk about value! $25 a month for life for Cable ONE Phone. Now you’ve got unlimited local calling and FREE 25 long distance in the continental U.S. All with no contract and a 30-Day Money-Back Guarantee. It’s the best FOR LIFE deal on the most reliable phone service. $25 a month for life. Don’t wait! 1-855-CABLE-ONE cableone.net *Limited Time Offer. Promotional rate quoted good for eligible residential New Customers. Existing customers may lose current discounts by subscribing to this offer. Changes to customer’s pre-existing services initiated by customer during the promotional period may void Phone offer discount. Offer cannot be combined with any other discounts or promotions and excludes taxes, fees and any equipment charges. -

Request for Information to Improve Federal Scientific Integrity Policies (86 FR 34064)

July 27, 2021 Office of Science and Technology Policy Executive Office of the President Eisenhower Executive Office Building 1650 Pennsylvania Avenue Washington, DC 20504 Submitted electronically to [email protected] Re: Request for Information to Improve Federal Scientific Integrity Policies (86 FR 34064) The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Association of American Universities (AAU), Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU), and Council on Governmental Relations (COGR), collectively the “Associations,” appreciate the opportunity to provide feedback to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to help improve the effectiveness of Federal scientific integrity policies in enhancing public trust in science. The Associations strongly support the efforts of the White House in addressing issues of federal scientific integrity and public trust in science. We further appreciate the swift issuance of the Presidential Memorandum on Restoring Trust in Government Through Scientific Integrity and Evidence-Based Policymaking and establishment of the Scientific Integrity Task Force. These actions seek to formalize and standardize scientific integrity through an all-of-government approach. Protecting the integrity of science and ensuring the use of evidence in policymaking should be a national priority across administrations. These efforts come at a critical time for the United States. Public trust in federal science has been shaken by anti-science rhetoric, lack of transparency, and questions about the integrity of science conducted and supported by the federal government. At the same time, building and maintaining trust in this science has never been more important as we confront continuing threats, including a global pandemic and climate change. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Sports in French Culture

Sporting Frenchness: Nationality, Race, and Gender at Play by Rebecca W. Wines A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Romance Languages and Literatures: French) in the University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Jarrod L. Hayes, Chair Professor Frieda Ekotto Professor Andrei S. Markovits Professor Peggy McCracken © Rebecca W. Wines 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Jarrod Hayes, the chair of my committee, for his enthusiasm about my project, his suggestions for writing, and his careful editing; Peggy McCracken, for her ideas and attentive readings; the rest of my committee for their input; and the family, friends, and professors who have cheered me on both to and in this endeavor. Many, many thanks to my father, William A. Wines, for his unfailing belief in me, his support, and his exhortations to write. Yes, Dad, I ran for the roses! Thanks are also due to the Team Completion writing group—Christina Chang, Andrea Dewees, Sebastian Ferarri, and Vera Flaig—without whose assistance and constancy I could not have churned out these pages nor considerably revised them. Go Team! Finally, a thank you to all the coaches and teammates who stuck with me, pushed me physically and mentally, and befriended me over the years, both in soccer and in rugby. Thanks also to my fellow fans; and to the friends who I dragged to watch matches, thanks for your patience and smiles. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iv Introduction: Un coup de -

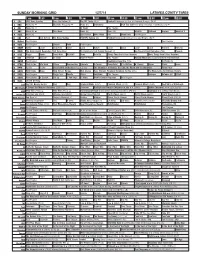

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

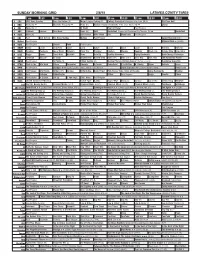

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Policy on Scientific Integrity

وزارة اﻟﺘﻌﻠﯿﻢ MINISTRY OF EDUCATION ﺟـﺎﻣﻌﺔ اﻟﺪﻣـﺎم UNIVERSITY OF DAMMAM اﻟﻤﺠﻠﺲ اﻟﻌﻠﻤﻲ THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Policy on Scientific Integrity Part I Rules & Regulations Policy on Scientific Integrity 2 Table of Contents Article Pages # Introduction 4 Definition of Scientific Misconduct in Research & 4 Scientific Studies General Rules of Scientific Integrity 5 Prevention of Scientific Misconduct in Research & 10 Scientific Studies Violations of Scientific Integrity 11 Management of Possible Scientific Misconduct 13 Record Retention 14 Applicability 15 General Definitions 15 Acknowledgements 22 Appendices 22 NSTIP Rules of Scientific Integrity 22 3 Policy on Scientific Integrity 1. Introduction The University of Dammam (UOD) espouses to maintain the highest standards of research ethics and scientific integrity. To that end, UOD has developed a series of policies and associated initiatives to promote a culture of scientific integrity and research ethics in the conduct of all aspects of its research mission. This commitment includes programs to educate all institutional members of such standards and to monitor the conduct of all scientific endeavors. This Policy for Scientific Integrity consists of four parts. They are: Part I: Rules and Regulations Part II: Rules for Scientific Publications, Authorship and Copyrights Part III: Research Conflict of Commitment and Conflict of Interest Part IV: Procedures for Evaluation and Management of Scientific Misconduct and Research Conflict of Commitment & Conflict of Interest In their collective, these parts articulate the institutional guidelines for proper scientific conduct and provides a detailed description of the institution’s management of any potential aberration to that standard. 2. Definition of Misconduct in Scientific Research Integrity Misconduct in research and scientific studies means fabrication, falsification, and/or plagiarism, in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results. -

Science and Technology Issues in the 117Th Congress

Science and Technology Issues in the 117th Congress May 5, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46787 SUMMARY R46787 Science and Technology Issues in the 117th May 5, 2021 Congress Frank Gottron, The federal government supports scientific and technological advancement directly by funding Coordinator and performing research and development, and indirectly by creating and maintaining policies Specialist in Science and that encourage private sector efforts. Additionally, the federal government regulates many Technology Policy aspects of S&T activities. This report briefly outlines a key set of science and technology policy th issues that may come before the 117 Congress. Brian E. Humphreys, Coordinator Many of these issues carry over from previous Congresses, and represent areas of continuing Analyst in Science and Member interest. Examples include policies on taxation, trade, intellectual property, Technology Policy commercialization of basic scientific research and other overarching issues that affect scientific and technological progress. Other issues may represent new or rapidly evolving areas affected by the threats of pandemic diseases, climate change, and malicious cyber activities, among others. Examples covered in this report include infectious disease modeling and forecasting, digital contact tracing and digital exposure notification, hydrogen pipelines, and expansion of emerging information and communications technologies such as 5G. These and other S&T-related issues that may come before the 117th Congress are grouped into 10 categories. Overarching S&T Policy Issues, Agriculture, Biotechnology and Biomedical Research and Development, Climate Change and Water, Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, Information Technology, Physical and Material Sciences, and Space. Each of these categories includes concise analysis of multiple policy issues. -

ENERI Manual Research Integrity and Ethics

ENERI Deliverable D3.1 Appendix: Manual ENERI Manual Research Integrity and Ethics Bart Penders | David Shaw | Peter Lutz | David Townend Lloyd Akrong | Olga Zvonareva Maastricht University 1 Table of Contents Introduction: the manual to the manual .................................................................................................. 3 It’s alive .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Research Integrity ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Conceptual issues ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1.1. The Researcher in Society - towards the “virtuous researcher” ........................................... 5 1.1.2 Research, Evidence and Truth? ............................................................................................. 9 1.1.3 Detrimental Research Practices and Research Misconduct ................................................. 12 1.1.4 Social Responsibility .......................................................................................................... 14 1.2. Practical Issues .......................................................................................................................... 18 1.2.1. Plagiarism .......................................................................................................................... -

Scientific Integrity

Scientific Integrity SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY The Rules of Academic Research by Kees Schuyt Translated by Kristen Gehrman LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS Translation: Kristen Gehrman Cover design: Geert de Koning Lay-out: Friedemann bvba ISBN 978 90 8728 230 1 e-ISBN 978 94 0060 218 2 (PDF) e-ISBN 978 94 0060 219 9 (ePUB) nur 737, 738 © Kees Schuyt / Leiden University Press, 2019 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/4.0/. This book is distributed in North America by the University of Chicago Press www.press.uchicago.edu. Table of contents Foreword 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Scientific integrity: an exploration of an elusive concept 13 1.1 Discredited by fraud 13 1.2 Integrity as a standard linked to one’s position 15 1.3 Integrity as a standard for one’s own behavior 18 1.4 Scientific values and the basic standards of integrity 21 1.5 Scientific integrity in practice: an initial exploration 25 Chapter 2 The codification of behavioral standards for scientific research 31 2.1 Muddying the waters of science: the Stapel affair 31 2.2 Some examples of fraud 32 2.3 Four conceptual distinctions 35 2.4 The emergence of norms in scientific practice 36 2.5 A case study: the codification of norms in the Netherlands 41 2.6 The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Scientific Practice of 2004/2012/2014 45 2.7 The Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity of 2018 49 Chapter 3 Scientific fraud: lessons from history -

Open-Ended Responses

Progress and Problems: Government Scientists Report on Scientific Integrity at Four Agencies Appendix D: Open-ended Responses Below are all open-ended responses received on the survey. Responses have not been edited for grammar or spelling errors. They are displayed as respondents wrote them, with identifying information redacted to protect anonymity. In some cases, large portions of responses had to be concealed to protect the identities of respondents. Question 39. How do you think the mission of the [AGENCY] and the integrity of the scientific work produced by the [AGENCY] could best be improved? The below open-ended responses are sorted by agency and categorized by subject, in order of frequency. The percentages in each category represent the proportion of coded text on that topic, rather than the proportion of respondents. CDC Twenty-six percent (467) of the 1,764 CDC survey respondents provided written responses. Management and Leadership (Mentioned in 26% of coded responses) Reduce/relax the beaurocratic procedures especially regarding publication of scientific work As a leading federal government agency, CDC should pay more attention to avoid nepotism within the same unit (branch or maybe division). This is especially a problem in the leadership level. It created unfair situation to other employee. People who enjoy these advantage often tend to chose their own favorite colleagues in important tasks, or assignments. This in turns created more opportunities to promote people of their own circle. The best man/woman for the particular task could therefore sacrifice because of this established culture of nepotism. OMB is a pain in the ass - the Paperwork Reduction Act is a joke. -

White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update

CSE’s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update Editorial Policy Committee (2011-2012) www.CouncilScienceEditors.org CSE’s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update Editorial Policy Committee (2011-2012) www.CounsilScienceEditors.org Kristi Overgaard (Chair) Daniel Salsbury American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Patricia Baskin Mary Scheetz American Academy of Neurology Research Integrity Consulting, LLC Elizabeth Blalock Diane Scott-Lichter Journal of Investigative Dermatology American Association for Cancer Research Howard Browman Gene P. Snyder Institute of Marine Research, Storebø, Norway Envision Pharma Bruce Dancik Anna Trudgett NRC Research Press, University of Alberta American Society of Hematology Wim D’Haeze Arena Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Editorial Policy Committee (2008-2009) Robert L. Edsall Heather Goodell (Chair) American Academy of Family Physicians American Heart Association Jill Filler Elizabeth Blalock American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Journal of Investigative Dermatology Heather Goodell Bruce Dancik American Heart Association NRC Research Press, University of Alberta Angela Hartley Robert L. Edsall Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses American Academy of Family Physicians Kenneth Kornfield Jill Filler American Society of Clinical Neurology American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Christine Laine Angela Hartley