Architectural Appraisal of Ho Tung Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing the Dead to Life: Identification, Interpretation, and Display of Chinese Burial Objects in the Rewi Alley Collection at Canterbury Museum

Bringing the Dead to Life: Identification, Interpretation, and Display of Chinese Burial Objects in the Rewi Alley Collection at Canterbury Museum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History University of Canterbury Siobhan O’Brien 2016 Contents List of Figures 1 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Chapter One: History and Provenance of Chinese Burial Objects with identification of examples from the Rewi Alley Collection 14 Chapter Two: The Ontological and Theoretical Complexities of Burial Objects in Museums 44 Chapter Three: Modes of Display of Chinese Burial Objects from the Rewi Alley Collection at Canterbury Museum 75 Conclusion 104 Bibliography 106 Figures 119 1 List of Figures Fig.1 Model of Granary, Han Dynasty (206 B.C.- 220 A.D.), baked earthenware with green pigment, 110x89x141mm (l x w x h), Rewi Alley Collection, Canterbury Museum, Accession number C1948.40, Source: ‘China, Art and Cultural Diplomacy’,(http://ucomeka1p.canterbury.ac.nz/items/show/671) Accessed August 4, 2015. Fig.2 Model of Granary, Han Dynasty (206 B.C.- 220 A.D.), baked earthenware with green pigment, 97x98x223mm (l x w x h), excavated at Wu Wei, Gansu Province, Rewi Alley Collection, Canterbury Museum, Accession number C1947.8, Source: ‘China, Art and Cultural Diplomacy’, (http://ucomeka1p.canterbury.ac.nz/items/show/669) Accessed August 4 2015. Fig.3 Model of Well-Head, Han Dynasty (206 B.C.- 220 A.D.), baked earthenware with green pigment, 115x106x224mm (l x w x h), excavated at Wu Wei, Gansu Province, Rewi Alley Collection, Canterbury Museum, Accession number C1947.9, Source: ‘China, Art and Cultural Diplomacy’, (http://ucomeka1p.canterbury.ac.nz/items/show/670) Accessed August 4 2015. -

HONG KONG STYLE URBAN CONSERVATION Dr. Lynne D. Distefano, Dr. Ho-Yin Lee Architectural Conservation Programme Department Of

Theme 1 Session 1 HONG KONG STYLE URBAN CONSERVATION Dr. Lynne D. DiStefano, Dr. Ho-Yin Lee Architectural Conservation Programme Department of Architecture The University of Hong Kong [email protected], [email protected] Katie Cummer The University of Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract. This paper examines the evolution of the field of conservation in the city of Hong Kong. In parti- cular, highlighting the ways in which conservation and urban development can be complementary forces instead of in opposition. The city of Hong Kong will be briefly introduced, along with the characteristics that define and influence its conservation, before moving on to the catalyst for Hong Kong’s conservation para- digm shift. The paper will proceed to highlight the various conservation initiatives embarked upon by the Hong Kong SAR’s Development Bureau, concluding with a discussion of the bureau’s accomplishments and challenges for the future. Introduction: Hong Kong Yet, Hong Kong is more than its harbour and more than a sea of high rises. Hong Kong’s main island, Usually, when people think of Hong Kong, the first what is properly called Hong Kong Island, is one of image that comes to mind is the “harbourscape” of some 200 islands and one of three distinct parts of the north shore of Hong Kong Island (Figure 1). This the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. is a landscape of high-rise buildings pressed together Hong Kong Island was leased to the British as a and protected at the back by lush hills, terminating in treaty port in 1841. From the beginning, the City of what is called “The Peak. -

LC Paper No. CB(2)1105/07-08(01) for Discussion on 22 February

LC Paper No. CB(2)1105/07-08(01) For discussion on 22 February 2008 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Subcommittee on Heritage Conservation Preservation of King Yin Lei at 45 Stubbs Road, Hong Kong PURPOSE This paper informs Members of the latest position regarding the declaration of King Yin Lei (including the associated buildings and its garden) (the “Building”) as a proposed monument on 15 September 2007 (L.N. 175 of 2007 refers) and seek Members’ views on the preservation proposals. BACKGROUND 2. The declaration of the Building as a proposed monument was made by the Authority (i.e. Secretary for Development) on 15 September 2007 after consultation with the Antiquities Advisory Board (AAB) under section 2A of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53). The purposes of the declaration are to give the Building temporary statutory protection from further damage (the Building faced an immediate threat as some works had been carried out at the site to remove the roof tiles, stone features and window frames of the Building), to allow a period of up to 12 months for the Authority to consider in a comprehensive manner whether it should be declared as a monument and to discuss with the owner feasible options for preservation of the Building. Unless it is withdrawn earlier, the proposed monument declaration will expire after 14 September 2008. ASSESSMENT OF HERITAGE VALUE 3. Subsequent to the proposed monument declaration, the Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) has engaged experts both locally and from the Mainland to assess the heritage value of the Building and the scale of damage to the Building, and to advise on possible restoration options. -

Administration's Paper on Mass Transit Railway South Island Line

File Ref.: THB(T)CR 17/1016/99 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF MASS TRANSIT RAILWAY SOUTH ISLAND LINE INTRODUCTION At the meeting of the Executive Council on 18 December 2007, the Council ADVISED and the Chief Executive ORDERED that – (a) the MTRCL should be asked to proceed with the preliminary planning and design of SIL (East); (b) negotiations with the MTRCL on the detailed scope, cost and implementation programme for SIL (East) should commence; (c) the Wong Chuk Hang Estate site should be reserved for the SIL depot with above-depot private property development, and the site to the north of the Ocean Park Station should be reserved for private property development with associated park and ride facilities, both subject to rezoning approval; and (d) Route 4 and the MTRCL’s proposed SIL (West) should continue to be kept under review. 2. The background on the SIL (East), SIL (West) and Route 4 is set out at Annex. JUSTIFICATIONS Transport and Economic Justifications Traffic Congestion along Aberdeen Tunnel 3. The residential and commercial nodes in the Southern District mainly stretch along two clusters with one on the west, namely the Cyberport, Pok Fu Lam, Wah Fu Estate and Aberdeen, and another lying to the east, namely South Horizons, Lei Tung Estate, Wong Chuk Hang and the Ocean Park. In going to the city areas, the former cluster relies more on Pokfulam Road and Victoria Road, and the latter on the Aberdeen Tunnel. The Southern District is the only remaining district Page 1 in Hong Kong with no rail service. 4. At present, traffic piles back from the Cross Harbour Tunnel and Causeway Bay daily in the peak hours and in turn causes congestion in the Aberdeen Tunnel. -

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

T It W1~~;T~Ril~T,~

University of Hong Kong Libraries Publications, No.7 LIBRARIES AND INFORMATION CENTRES IN HONG KONG t it W1~~;t~RIl~t,~ Compiled and edited by Julia L.Y. Chan ~B~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., FHKLA Angela S.W. Van I[I~Uw~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., A.A.L.I.A. Kan Lai-bing MBiJl( B.Sc., M.A., M.L.S., Ph.D., Hon. D.Litt, A.L.A.A., M.I.Inf. Sc., FHKLA Published for The Hong Kong Library Association by Hong Kong University Press * 1~ *- If ~ )i[ ltd: Hong Kong University Press 139 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1996 ISBN 962 209 409 0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by United League Graphic & Printing Company Limited Contents Plates Preface xv Introduction xvii Abbreviations & Acronyms xix Alphabetical Directory xxi Organization Listings, by Library Types 533 Libraries Open to the Public 535 Post-Secondary College and University Libraries 538 School Libraries 539 Government Departmental Libraries 550 HospitallMedicallNursing Libraries 551 Special Libraries 551 Club/Society Libraries 554 List of Plates University of Hong Kong Main Library wnt**II:;:tFL~@~g University of Hong Kong Main Library - Electronic Infonnation Centre wnt**II:;:ffr~+~~n9=t{., University of Hong Kong Libraries - Chinese Rare Book Room wnt**II:;:i139=t)(~:zjs:.~ University of Hong Kong Libraries - Education -

For Discussion on 15 July 2011

CB(1)2690/10-11(03) For discussion on 15 July 2011 Legislative Council Panel on Development Progress Report on Heritage Conservation Initiatives and Revitalisation of the Old Tai Po Police Station, the Blue House Cluster and the Stone Houses under the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme PURPOSE This paper updates Members on the progress made on the heritage conservation initiatives under Development Bureau’s purview since our last progress report in November 2010 (Legislative Council (LegCo) Paper No. CB(1)467/10-11(04)), and invites Members’ views on our future work. It also seeks Members’ support for the funding application for revitalising the Old Tai Po Police Station, the Blue House Cluster and the Stone Houses under the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme (Revitalisation Scheme). PROGRESS MADE ON HERITAGE CONSERVATION INITIATIVES Public Domain Revitalisation Scheme Batch I 2. For the six projects under Batch I of the Revitalisation Scheme, the latest position is as follows – (a) Former North Kowloon Magistracy – The site has been revitalised and adaptively re-used as the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Hong Kong Campus for the provision of non-local higher education courses in the fields of art and design. Commencing operation in September 2010, SCAD Hong Kong is the first completed project under the Revitalisation Scheme. For the Fall 2010 term, 141 students were enrolled, of which about 40% are local students. In April 2011, SCAD Hong Kong obtained accreditation from the Hong Kong Council for Accreditation of Academic and Vocational Qualifications for five years for 14 programmes it offers at the Hong Kong campus. -

DEVB(W)-E2.Doc

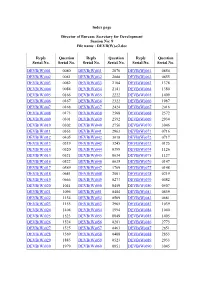

Index page Director of Bureau: Secretary for Development Session No: 9 File name : DEVB(W)-e2.doc Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. DEVB(W)001 0080 DEVB(W)031 2070 DEVB(W)061 0854 DEVB(W)002 0081 DEVB(W)032 2088 DEVB(W)062 0855 DEVB(W)003 0082 DEVB(W)033 2104 DEVB(W)063 1378 DEVB(W)004 0084 DEVB(W)034 2141 DEVB(W)064 1380 DEVB(W)005 0166 DEVB(W)035 2222 DEVB(W)065 1409 DEVB(W)006 0167 DEVB(W)036 2322 DEVB(W)066 1987 DEVB(W)007 0168 DEVB(W)037 2424 DEVB(W)067 2016 DEVB(W)008 0173 DEVB(W)038 2568 DEVB(W)068 2572 DEVB(W)009 0301 DEVB(W)039 2592 DEVB(W)069 2934 DEVB(W)010 0302 DEVB(W)040 2756 DEVB(W)070 3046 DEVB(W)011 0363 DEVB(W)041 2963 DEVB(W)071 0716 DEVB(W)012 0405 DEVB(W)042 3018 DEVB(W)072 0717 DEVB(W)013 0519 DEVB(W)043 3245 DEVB(W)073 0125 DEVB(W)014 0520 DEVB(W)044 0399 DEVB(W)074 1126 DEVB(W)015 0521 DEVB(W)045 0634 DEVB(W)075 1127 DEVB(W)016 0522 DEVB(W)046 0635 DEVB(W)076 0147 DEVB(W)017 0589 DEVB(W)047 1769 DEVB(W)077 0148 DEVB(W)018 0641 DEVB(W)048 2001 DEVB(W)078 0219 DEVB(W)019 0666 DEVB(W)049 0273 DEVB(W)079 0482 DEVB(W)020 1041 DEVB(W)050 0459 DEVB(W)080 0507 DEVB(W)021 1096 DEVB(W)051 0484 DEVB(W)081 0639 DEVB(W)022 1154 DEVB(W)052 0509 DEVB(W)082 0681 DEVB(W)023 1155 DEVB(W)053 2965 DEVB(W)083 1039 DEVB(W)024 1404 DEVB(W)054 1994 DEVB(W)084 1040 DEVB(W)025 1523 DEVB(W)055 0049 DEVB(W)085 1405 DEVB(W)026 1524 DEVB(W)056 0281 DEVB(W)086 2773 DEVB(W)027 1525 DEVB(W)057 0463 DEVB(W)087 2851 DEVB(W)028 1569 DEVB(W)058 0488 DEVB(W)088 2853 DEVB(W)029 1885 DEVB(W)059 0523 DEVB(W)089 2953 DEVB(W)030 1979 DEVB(W)060 0851 DEVB(W)090 3045 Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. -

New Item Nos. N337, N338 & N261

N337 Historic Building Appraisal Entrance Gate San Wai, Ha Tsuen, Yuen Long, New Territories The entrance gate of San Wai (新圍), which literally means “new Historical walled village”,1 is situated in a local district known as Ha Tsuen (廈村) or Interest Ha Tsuen Heung (廈村鄉).2 Ha Tsuen was founded by two brothers, Tang Hung-chi (鄧洪贄) and Tang Hung-wai (鄧洪惠), both ninth generation members of the Ng Yuen Tso (五元祖) of the Tang (鄧) clan.3 As one of the oldest villages in Ha Tsuen, San Wai has a history of more than 250 years. It was established by Tang Tso-tai (鄧作泰, 1695 – 1756), an eighteenth generation member of the Ng Yuen Tso, and Tang Wai-yuk (鄧為玉, 1715 – 1755), a generation younger than Tso-tai. The village’s name “新圍” in Chinese and “San Wai” in English can be identified from a government report of 1899 and a land record of the then colonial government dating from 1905 to 1907. Regarding its layout, San Wai is composed of rows of houses, with an entrance gate. It is believed that the entrance gate was originally situated on the central axis of the village. As the village expanded, this central axis gradually lost its significance, and the view from the entrance gate was eventually blocked by rows of houses. A map dated 1917, which is the earliest record of its kind identified, shows that by that time two rows of houses had been built in front of the entrance gate.4 Interestingly, no shrine was built within San Wai, as villagers believe that the village is “protected” by the Earth God shrine near the Yeung Hau Temple (楊侯古廟), which is locally known as Sai Tau Miu (西頭廟, western temple). -

Next Generation

January/February 2018 Volume 191 Next Generation Interview with a Chief 4 Fuel for the future Tom Uiterwaal, Founder and CEO, Reconergy (HK) Ltd Mentoring & learning on one’s own terms 16 Are you ready to be a young entrepreneur? 22 The magazine for members of the Dutch Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong Contents Suite 3002, 30th Floor 3 Chairman’s Note Central Plaza 18 Harbour Road Wan Chai 4 Interview with a Chief Hong Kong Fuel for the future E-mail: [email protected] Tom Uiterwaal, Founder and CEO, Website: www.dutchchamber.hk Reconergy (HK) Ltd Skype: Dutchchamberhk 6 News & Views Editorial Committee Jacob Feenstra (Chair) Judith Huismans 16 Lead Story Maarten Swemmer Mentoring and learning C Monique Detilleul on one’s own terms M Merel van der Spiegel Alfred Tse Y 20 Passing the Pen CM Editor MY Donna Mah 21 Go Green CY Desktop Publisher 22 Tax Focus CMY Just Media Group Ltd K 24 China Focus General Manager Muriel Moorrees 25 Legal Focus Cover Design Saskia Wesseling 26 Passport to Hong Kong Advertisers 28 Lifestyle ABN AMRO BANK N.V. CUHK BUSINESS SCHOOL 31 Events GLENEAGLES HONG KONG HOSPITAL ING BANK N.V., HONG KONG BRANCH 34 Members’ Corner JUST MEDIA GROUP LTD. PHILIPS ELECTRONICS HONG KONG RABOBANK HONG KONG 35 Enquiries and Information TANNER DE WITT TURKISH AIRLINES 36 DutchCham Information This magazine is distributed free of charge to all members and relations of the Dutch Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. For annual subscription, please mail your business card and a crossed cheque for HK$490 to the above address. -

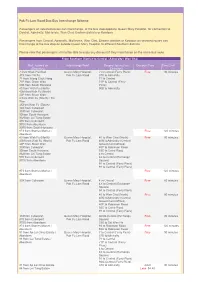

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme

Pok Fu Lam Road Bus-Bus Interchange Scheme Passengers on selected routes can interchange, at the bus stop opposite Queen Mary Hospital, for connection to Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon. Passengers from Central, Admiralty, Mid-levels, Wan Chai, Eastern districts or Kowloon on selected routes can interchange at the bus stop on outside Queen Mary Hospital, to different Southern districts. Please note that passengers will not be able to enjoy any discount if they interchange on the same bus route. From Southern District to Central / Admiralty / Wan Chai First Journey on Interchange Point Second Journey on Discount Fare Time Limit (Direction) (Direction) 7 from Shek Pai Wan Queen Mary Hospital, 7 to Central (Ferry Piers) Free 90 minutes 37X from Chi Fu Pok Fu Lam Road 37X to Admiralty 71 from Wong Chuk Hang 71 to Central 71P from Sham Wan 71P to Central (Ferry 90B from South Horizons Piers) 40 from Wah Fu (North) 90B to Admiralty 40M fromWah Fu (North) 40P from Sham Wan 4 from Wah Fu (South) / Tin Wan 4Xfrom Wah Fu (South) 30X from Cyberport 33Xfrom Cyberport 93from South Horizons 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate 970 from Cyberport 970X from Aberdeen X970 from South Horizons 973 from Stanley Market / Free 120 minutes Aberdeen 40 from Wah Fu (North) Queen Mary Hospital, 40 to Wan Chai (North) Free 90 minutes 40M from Wah Fu (North) Pok Fu Lam Road 40M toAdmiralty (Central 40P from Sham Wan Government Offices) 33X from Cyberport 40P to Robinson Road 93from South Horizons 93C to Caine Road 93Afrom Lei Tung Estate -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c.