The Case of Plaka in Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See Attachment

T able of Contents Welcome Address ................................................................................4 Committees ............................................................................................5 10 reasons why you should meet in Athens....................................6 General Information ............................................................................7 Registration............................................................................................11 Abstract Submission ............................................................................12 Social Functions....................................................................................13 Preliminary Scientific Program - Session Topics ..........................14 Preliminary List of Faculty..................................................................15 Hotel Accommodation..........................................................................17 Hotels Description ................................................................................18 Optional Tours........................................................................................21 Pre & Post Congress Tours ................................................................24 Important Dates & Deadlines ............................................................26 3 W elcome Address Dear Colleagues, You are cordially invited to attend the 28th Politzer Society Meeting in Athens. This meeting promises to be one of the world’s largest gatherings of Otologists. -

With Samos & Kuşadası

GREECE with Samos & Kuşadası Tour Hosts: Prof. Douglas Henry & MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 Prof. Scott Moore organized by Baylor University in GREECE with Samos & Kuşadası / MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 Corinth June 1 Fri Athens - Eleusis - Corinth Canal - Corinth - Nafplion (B,D) June 2 Sat Nafplion - Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon - Epidaurus - Nafplion (B, D) June 3 Sun Nafplion -Church of Agia Fotini in Mantinea- Tripolisand Megalopolis-Mystras-Kalamata (B,D) BAYLOR IN GREECE June 4 Mon Kalamata - Drive by Methoni or Koroni to see the Venetian fortresses - Nestor’s Palace in Pylos (B,D) Program Directors: Douglas Henry and Scott Moore June 5 Tue Pylos - Tours in the surrounding area - more details will follow by Nick! (B,D) MAY 27 - JUNE 23, 2018 June 6 Wed Pylos - Gortynia - Dimitsana - Olympia (B, D) June 7 Thu Olympia - Temple of Zeus, the Temple of Hera, Museum - Free afternoon. Overnight Olympia (B,D) Acropolis, Athens June 8 Fri Olympia - Morning drive to the modern city of Corinth. Overnight Corinth. (B,D) June 9 Sat Depart Corinth for Athens airport. Fly to Samos. Transfer to hotel. Free afternoon, overnight in Samos (B,D) June 10 Sun Tour of Samos; Eupalinos Tunnel, Samos Archaeological Museum, walk in Vathi port. (B,D) June 11 Mon Day trip by ferry to Patmos. Visit the Cave of Revelation and the Basilica of John. Return Samos. (B,D) June 12 Tue Depart Samos by ferry to Kusadasi. Visit Miletus- Prienne-Didyma, overnight in Kusadasi (B,D) Tour Itinerary: May 27 Sun Depart USA - Fly Athens May 28 Mon Arrive Athens Airport - Private transfer to Hotel. -

Classics in Greece J-Term Flyer

WANG CENTER WANG Ancient Greece is often held in reverential awe, and Excursions around Greece to places including: praised for its iconic values, contributions, • Epidaurus: a famous center of healing in antiquity and site and innovations. However, much of what has been of one of the best preserved Greek theaters in the world considered iconic is, in fact, the product of a • Piraeus, Cape Sounion, and the Battle site of Marathon western classical tradition that re-imagines and re- • Eleusis, Corinth, Acrocorinth, and Corinth Canal fashions its ancient past to meet its present • Nauplion, a charming seaside city and the first capital of AWAY STUDY J-TERM needs. In this course, you will explore the romance modern Greece – and the realities – of ancient Greece in Greece. • Mycene and Tiryns, the legendary homes of Agamemnon and the hero Herakles Explore Athens, the birthplace of democracy, and • Ancient Olympia: where the original Olympics were the ruins of Mycenae, from which the Trojan War celebrated. was launched. Examine the evidence for yourself • The mountain monastery, and UNESCO World Heritage in Greece’s many museums and archeological site, of Hosios Loukas. sites. Learn how the western classical heritage has • Delphi: the oracle of the ancient world. reinvented itself over time, and re-envision what • Daytrip to Hydra island (optional). this tradition may yet have to say that is relevant, fresh, and contemporary. Highlights include exploring Athens, its environments, and the Peloponnesus with expert faculty. Scheduled site visits include: • Acropolis and Parthenon • Pnyx, Athenian Agora, and Library of Hadrian • Temples of Olympian Zeus, Hephaistus, and Asclepius • Theaters of Dionysus and Odeon of Herodes Atticus • Plaka and Monastiraki flea market • Lycebettus Hill, and the neighborhoods of Athens • National Archeological, New Acropolis, and Benaki museums “Eternal Summer Gilds Them Yet”: The Literature, Legend, and Legacy of Ancient Greece GREECE Educating to achieve a just, healthy, sustainable and peaceful world, both locally and globally. -

The Athenian Prytaneion Discovered? 35

HESPERIA 75 (2006) THE ATHENIAN Pages 33-81 PRYTANEION DISCOVERED? ABSTRACT The author proposes that the Athenian Prytaneion, one of the city's most important civic buildings, was located in the peristyle complex beneath Agia Aikaterini Square, near the ancient Street of the Tripods and theMonument of Lysikrates in the modern Plaka. This thesis, which is consistent with Pausa s nias topographical account of ancient Athens, is supported by archaeological and epigraphical evidence. The identification of the Prytaneion at the eastern foot of the Acropolis helps to reconstruct the map of Archaic and Classical Athens and illuminates the testimony of Herodotos and Thucydides. most The Prytaneion is the oldest and important of the civic buildings in to us ancient Athens that have remained lost until the present.1 For the or Athenians the Prytaneion, town hall, the office of the city's chief official, as a symbolized the foundation of Athens city-state, its construction form ing an integral part of Theseus's legendary synoecism of Attica (Thuc. 2.15.2; Plut. Thes. 24.3). Like other prytaneia throughout the Greek world, the Athenian Prytaneion represented what has been termed the very "life common of the polis," housing the hearth of the city, the "inextinguishable and immovable flame" of the goddess Hestia.2 As the ceremonial center was of Athens, the Prytaneion the site of both public entertainment for 1.1 am to the to a excellent for greatly indebted express my heartfelt thanks number suggestions improving this 1st Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classi of scholars who have given generously article. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

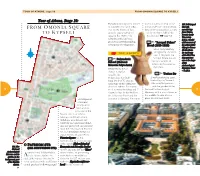

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Ciné Paris Plaka Kidathineon 20

CINÉ PARIS PLAKA KIDATHINEON 20 UPDATED: MAY 2019 Dear Guest, Thank you for choosing Ciné Paris Plaka for your stay in Athens. You have chosen an apartment in the heart of Athens, in the old town of Plaka. In the shadow of the Acropolis and its ancient temples, hillside Plaka has a village feel, with narrow cobblestone streets lined with tiny shops selling jewelry, clothes, local ceramics and souvenirs. Sidewalk cafes and family-run taverns stay open until late, and Cine Paris (next door) shows classic movies al fresco. Nearby, the whitewashed homes of the Anafiotika neighborhood give the small enclave a Greek-island vibe. Following is a small list of recommendations and useful information for you. It is by no means an exhaustive list as there are too many places to eat, drink and sight-see than we could possibly put down. Rather, this is a list of places that we enjoy and that our guests seem to like. We find that our guests like to discover things themselves. After all is that not a great part of the joy of traveling? To discover new experiences and places. We wish you a wonderful stay, and we hope you love Athens! __________________________________________________ The site to purchase tickets online for the Acropolis and slopes, The Temple of Olympian Zeus, Kerameikos, Ancient Agora, Roman Agora, Adrians Library and Aristotle's School is here https://etickets.tap.gr/ Once you access the site in the left-hand corner there are the letters EΛ|EN; click on the EN for English. MUSEUMS THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, Dionysiou Areopagitou 15, Athens 117 42 Summer season hours (1/4 – 31/10) Winter season hours (1/11 – 31/3) Monday 8:00 - 16:00 Monday – Thursday 9:00 - 17:00 Tuesday – Sunday 8:00 – 20:00 Friday 9:00 - 22:00 Friday 8:00 a.m. -

Social Program for Delegates & Accompanyig

SOCIAL PROGRAM FOR ACCOMPANYIG PERSONS Saturday 13 Sep 2008 ATHENS CITY TOUR This tour gives you an opportunity to observe the striking contrasts that make Athens such a fascinating city. Our expert guides take you to see the centre of the city, Constitution Square (Syntagma), the House of Parliament, the Memorial to the Unknown Soldier and the National Library. Driving down Herodus Atticus Street, you will see the Evzones in their picturesque uniform and the Presidential Palace. On your way to the Acropolis, you will see the Panathenaic Stadium (where first Olympic Games of the modern era were held in 1896), the Temple of Olympian Zeus and Hadrian’s Arch. Depart for the Acropolis and the Parthenon. Guided tour of the Parthenon (Temple of Athena), the city’s divine patroness, Propylea (Monumental entrance gate), Temple of Wingless Victory and the Erechteion. From the Acropolis we see and comment about the theatre of Dionysus (the first of all western theatres). Continue to the Aeropagus, the open-air meeting place of the highest legislative and judicial body in Ancient Greece. Continue to the Ancient Agora, the civic, commercial and religious centre of the Athenian life. Visit the temple of Hephaestus and the restored Stoa of Attalus, erected by Attalus II, King of Pergamos and now used as a museum. Out of Greek Agora in the same area, is the Roman Market and the Clock of Andronikos Kyrhestes, the so-called Tower of the Winds. As you are near the Monastiraki area you will have the impression that you are entering a melting pot of sound; all kinds of music and voices of the street vendors can be heard simultaneously! The scent of the old wood and wood varnish, coming from the shops of antique furniture, predominant form Avisinias square, gives its place to that of new leather, in that part of Adrianou Street lined with shoe shops. -

Athens Guide

ATHENS GUIDE Made by Dorling Kindersley 27. May 2010 PERSONAL GUIDES POWERED BY traveldk.com 1 Top 10 Athens guide Top 10 Acropolis The temples on the “Sacred Rock” of Athens are considered the most important monuments in the Western world, for they have exerted more influence on our architecture than anything since. The great marble masterpieces were constructed during the late 5th-century BC reign of Perikles, the Golden Age of Athens. Most were temples built to honour Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Still breathtaking for their proportion and scale, both human and majestic, the temples were adorned with magnificent, dramatic sculptures of the gods. Herodes Atticus Theatre Top 10 Sights 9 A much later addition, built in 161 by its namesake. Acropolis Rock In summer it hosts the Athens Festival (see Festivals 1 As the highest part of the city, the rock is an ideal and Events). place for refuge, religion and royalty. The Acropolis Rock has been used continuously for these purposes since Dionysus Theatre Neolithic times. 10 This mosaic-tiled theatre was the site of Classical Greece’s drama competitions, where the tragedies and Propylaia comedies by the great playwrights (Aeschylus, 2 At the top of the rock, you are greeted by the Sophocles, Euripides) were first performed. The theatre Propylaia, the grand entrance through which all visitors seated 15,000, and you can still see engraved front-row passed to reach the summit temples. marble seats, reserved for priests of Dionysus. Temple of Athena Nike (“Victory”) 3 There has been a temple to a goddess of victory at New Acropolis Museum this location since prehistoric times, as it protects and stands over the part of the rock most vulnerable to The Glass Floor enemy attack. -

Excursion Proposals for Pre-And Post Congress Tours

ACUUS 2007 - EXCURSION PROPOSALS 1. ATHENS CITY TOUR This tour gives you an opportunity to observe the striking contrasts that make Athens such a fascinating city. Our expert guides take you to see the centre of the city, Constitution Square (Syntagma), the House of Parliament, the Memorial to the Unknown Soldier and the National Library. Driving down Herodus Atticus Street, you will see the Evzones in their picturesque uniform and the Presidential Palace. On your way to the Acropolis, you will see the Panathenaic Stadium (where first Olympic Games of the modern era were held in 1896), the Temple of Olympian Zeus and Hadrian’s Arch. Depart for the Acropolis and the Parthenon. Guided tour of the Parthenon (Temple of Athena), the city’s divine patroness, Propylea (Monumental entrance gate), Temple of Wingless Victory and the Erechteion. From the Acropolis we see and comment about the theatre of Dionysus (the first of all western theatres). Continue to the Aeropagus, the open-air meeting place of the highest legislative and judicial body in Ancient Greece. Continue to the Ancient Agora, the civic, commercial and religious centre of the Athenian life. Visit the temple of Hephaestus and the restored Stoa of Attalus, erected by Attalus II, King of Pergamos and now used as a museum. Out of Greek Agora in the same area, is the Roman Market and the Clock of Andronikos Kyrhestes, the so-called Tower of the Winds. As you are near the Monastiraki area you will have the impression that you are entering a melting pot of sound; all kinds of music and voices of the street vendors can be heard simultaneously! The scent of the old wood and wood varnish, coming from the shops of antique furniture, predominant form Avisinias square, gives its place to that of new leather, in that part of Adrianou Street lined with shoe shops. -

Conference Guide

Conference Guide Conference Venue Conference Location: Radisson Blu Athens Park Hotel 5* 5Hotel Athens” Radisson Blu Park Hotel Athens first opened its doors in 1976 on the border of the central park of Athens, Pedion Areos (Martian Field), in a safe part of the city. For 35 years the lovely park has been a wonderful host and marked the very identity of this leading deluxe hotel. Now, we thought, it is time for the hotel to host the park inside. This was the inspiration behind our recent renovation, which came to prove a virtual rebirth for Park Hotel Athens. Address: 10 Alexandras Ave. -10682 Athens-Greece Tel: +30 210 8894500 Fax: +30 210 8238420 URL: http://www.rbathenspark.com/index.php History of Athens According to tradition, Athens was governed until c.1000 B.C. by Ionian kings, who had gained suzerainty over all Attica. After the Ionian kings Athens was rigidly governed by its aristocrats through the archontate until Solon began to enact liberal reforms in 594 B.C. Solon abolished serfdom, modified the harsh laws attributed to Draco (who had governed Athens c.621 B.C.), and altered the economy and constitution to give power to all the propertied classes, thus establishing a limited democracy. His economic reforms were largely retained when Athens came under (560–511 B.C.) the rule of the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. During this period the city's economy boomed and its culture flourished. Building on the system of Solon, Cleisthenes then established a democracy for the freemen of Athens, and the city remained a democracy during most of the years of its greatness. -

Athens – Greece, 8-11 October 2015

Serafim Sotiriades & Associates Law Office IAG Assembly Program & Information: Athens – Greece, 8-11 October 2015 Athens is considered one of the top destinations in the world. We will try to make this Assembly an unforgettable experience for you! The Program Thursday, 8 October 2015 Evening 19:00 Welcome drink and registration at the Electra Palace lounge-bar (lobby) Delegates and guests are welcomed in a private area at the Electra Palace with White Prosecco and the traditional Greek Ouzo drink. 20:00 Walk around Athens Ancient City Centre (15 minutes) We will fuel your appetite with a night-walk around Athens Ancient City Centre (15 minutes). During our first short walk, we will admire the narrow streets of Plaka, called “the neighbourhood of the Gods”, and Anafiotika area, that looks like a small island within Athens. 20:15 Greek Traditional Dinner at Plaka Area We will taste typical Greek dishes at the famous greek “tavernas”, all made of excellent quality fresh ingredients and flooded with the famous Greek olive oil. Tip: A taverna is a small Greek restaurant that serves traditional Greek cuisine, an integral part of Greek culture. Typical dishes are Greek salad, feta, mousakas, tzatziki, fava, ntolmadakia, etc. Special Interest Group: Starting with a Cocktail night at Plaka Area 4, Likavittou Street, 106 71 Athens – Greece Tel: +30-210 3388822, Fax: +30-210 3388813, e-mail: [email protected] Serafim Sotiriades & Associates Law Office Friday, 9 October 2015 Morning Business Session for delegates only. Includes lunch. The business session will take place in Electra Palace Ballroom. The detailed program to be announced. -

10-Day Tour of Greece

May 23 - June 1, 2005 Join Dr. David S. Dockery, President of Union University, and his special guests for a 10-day tour of Greece $3470.00 from New York Optional Tour of Rome - $850.00 (Academic Credit Available) Dr. Dockery’s Guests Include: Sam Shaw BuddyBuddy GrayGray Steve Gaines Union University Trustee Union Board of Reference Union University Alumnus Pastor, Germantown Pastor, Hunter Pastor Baptist Church Street Baptist Church First Baptist Church Germantown, TN Birmingham, AL Gardendale, AL Charles Fowler Jamie Parker Michael Miller Senior Vice-President Union University Alumnus Director, Church Relations, University Relations Worship Minister LifeWay Church Resources Union University First Baptist Church Nashville, TN Gardendale, AL Travel Arrangements by TE M P L E T ON TOURS INC. TTI 1 - 8 0 0 - 3 3 4 - 2 6 3 0 w w w. t e m p l e t o n t o u r s . c o m May 23 – DEPART USA May 27 – THESSALONIKI – VERIA – VERGINA – Today we meet at our international departure airport where KALAMBAKA our host will assist us with check-in formalities. This evening After breakfast we depart Thessaloniki and drive to Veria we will enjoy a delicious dinner high above the Atlantic. (Biblical Berea). Here Paul found a group of Jews “more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the May 24 – ARRIVE THESSALONIKI Word with all readiness of mind, and searched the Scriptures We arrive in Thessaloniki this afternoon. Upon arrival at daily, whether those things were so” (Acts 17:10-14). We will Thessaloniki International Airport our representative will meet visit a place where, according to tradition, Paul stood and us and transfer us to our hotel.