Espn the Magazine's Body Issue and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

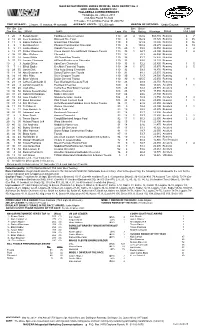

Nationwide Series Updated Driver Standings

Points Report Phoenix International Raceway 15th Annual ServiceMaster 200 UNOFFICIAL Provided by NASCAR Statistics - Saturday, 11/9/2013 @ 6:37 PM Eastern UNOFFICIAL Pos Driver BPts Points Ldr Nxt Starts Poles Wins T5s T10s DNF PPos G/L 1. Austin Dillon 19 1148 0 0 32 7 0 13 22 s1 1 0 2. Sam Hornish Jr. 21 1140 -8 -8 32 3 1 16 24 2 2 0 3. Regan Smith 18 1093 -55 -47 32 0 2 8 19 0 3 0 4. Justin Allgaier 8 1065 -83 -28 32 1 0 6 16 0 5 1 5. Elliott Sadler 9 1062 -86 -3 32 0 0 9 20 2 4 -1 6. Trevor Bayne 15 1047 -101 -15 32 1 1 6 20 1 7 1 7. Brian Scott 8 1041 -107 -6 32 1 0 3 13 1 6 -1 8. Brian Vickers 10 970 -178 -71 30 0 0 13 18 2 8 0 9. Kyle Larson # 7 957 -191 -13 32 0 0 8 16 7 9 0 10. Parker Kligerman 6 956 -192 -1 32 0 0 3 12 3 10 0 11. Alex Bowman # 3 884 -264 -72 32 2 0 2 6 1 11 0 12. Nelson Piquet Jr. # 0 827 -321 -57 32 0 0 0 4 3 12 0 13. Mike Bliss 2 807 -341 -20 32 0 0 0 2 3 13 0 14. Travis Pastrana 2 725 -423 -82 32 1 0 0 4 6 14 0 15. Michael Annett 2 669 -479 -56 24 0 0 1 4 3 15 0 16. -

Starting Line up by Row Phoenix International Raceway

Starting Line Up by Row Phoenix International Raceway WYPALL * 200 Powered by Kimberly Clark Professional Provided by NASCAR Statistics - Sat, November 13, 2010 @ 11:53 AM US Driver Date Time Speed Track Race Record: Jeff Burton 11/04/00 01:44:13 115.145 Pos Car Driver Team Time Speed Row 1: 1 20 Joey Logano GameStop/Afterglow Toyota 26.856 134.048 2 60 Carl Edwards Copart Ford 26.924 133.710 Row 2: 3 12 Justin Allgaier Verizon Wireless Dodge 27.006 133.304 4 33 Kevin Harvick Rheem Solar Water Heaters Chevrolet 27.043 133.121 Row 3: 5 18 Kyle Busch NOS Toyota 27.052 133.077 6 00 Martin Truex Jr. Travis Pastrana Toyota 27.084 132.920 Row 4: 7 98 Paul Menard Richmond/Menards Ford 27.091 132.885 8 66 Steve Wallace 5-hour Energy Toyota 27.110 132.792 Row 5: 9 17 Trevor Bayne Roush Fenway Ford 27.226 132.227 10 91 David Gilliland D'Hondt Humphrey Racing Chevrolet 27.233 132.193 Row 6: 11 38 Jason Leffler Great Clips Toyota 27.245 132.134 12 22 Brad Keselowski Discount Tire Dodge 27.246 132.129 Row 7: 13 99 Ryan Truex Aaron's Dream Machine Toyota 27.301 131.863 14 32 Reed Sorenson Dollar General Toyota 27.361 131.574 Row 8: 15 23 Coleman Pressley R3 Motorsports Chevrolet 27.380 131.483 16 09 Brian Scott # Shore Lodge Toyota 27.421 131.286 Row 9: 17 88 Aric Almirola GT Vodka Chevrolet 27.422 131.281 18 15 Michael Annett Pilot Flying J Coffee Toyota 27.434 131.224 Row 10: 19 27 Alex Kennedy LawMemorial.org/Sacred Power Ford 27.441 131.191 20 16 Colin Braun # Con-way Ford 27.444 131.176 Row 11: 21 36 Jeff Green Tri-Star Motorsports Chevrolet 27.454 131.128 22 6 Ricky Stenhouse Jr. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Flash Results, Inc. - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 10:45 AM 6/18/2021 Page 1 2020 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Track & Field - 6/18/2021 to 6/27/2021 Hayward Field Meet Program - June 18 Event 31 Men Shot Put Event 35 Men Hammer Throw Friday 6/18/2021 - 12:00 PM Friday 6/18/2021 - 12:05 PM 2 rings 3 throws each, top 12 advance to final 3 throws each, top 12 advance to final World: 86.74m 8/30/1986 Yuriy Sedykh break ties American: 82.52m 9/7/1996 Lance Deal World: 23.12m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes Meet: 80.12m 6/4/1992 Jud Logan American: 23.12m 5/20/1990 Randy Barnes OG Q: 77.50m Meet: 22.12m 7/15/2000 Adam Nelson PosName Team Seed Mark OG Q: 21.10m Flight 1 of 2 Prelims PosName Team Seed Mark 1 Morgan Shigo Velaasa Flight 1 of 2 Prelims 2 Manning Plater Illinois 1 David Pless Iron Wood TC 3 Sean Donnelly adidas 2 Josh Awotunde Shore AC 4 Victor Perez Unattached 3 John Meyer Michigan 5 Conor McCullough New York AC 4 Coy Blair Unattached 6 Avery Carter Unattached 5 Ryan Crouser NIKE 7 Alex Hill Ashland 6 Tripp Piperi Texas 8 Nathan Bultman Unattached 7 Roger Steen Velaasa 9 Austin Combs Findlay 8 T'Mond Johnson Garage Strength 10 Daniel Haugh Throw1Deep 9 Daniel McArthur North Carolina 11 Justin Stafford Unattached 10 Lucas Warning Garage Strength 12 Vlad Pavlenko Iowa State 11 Nik Curtiss Tiffin Flight 2 of 2 Prelims 12 Curtis Jensen Velaasa 1 Brock Eager Unattached Flight 2 of 2 Prelims 2 Erich Sullins Unattached 1 Jordan Geist Arizona 3 Ryan Davis East Carolina 2 Payton Otterdahl NIKE 4 Alex Young Unattached 3 McKay Johnson USC 5 Johnnie Jackson Unattached 4 Andrew Liskowitz Michigan 6 Colin Dunbar Unattached 5 Tyler Blalock Kennesaw St 7 Israel Oloyede Arizona 6 Jonah Wilson Washington 8 Mike Bryan Wichita State 7 Darrell Hill NIKE 9 Alex Talley North Dakota St 8 Darius King Northern Iowa 10 Tyler Merkley Penn State 9 Joe Kovacs Velaasa/NYAC 11 Rudy Winkler Tracksmith/NYA 10 Ralph Casper Tiffin 12 Michael Shanahan Chula Vista El 11 Matthew Katnik USC 12 Adam Kessler Drake Flash Results, Inc. -

1 Brand for Every Competition

Gymnova has a long history of supplying major Gymnastic events, in 2009 we were chosen as the equipment supplier for the 41st World Artistic Gymnastics Championships held in London, a year later we were the equipment supplier for the 2010 Commonwealth Games held in Delhi and m o c . o i d now the highest accolade is for us to be chosen as the Gymnastics Equipment supplier for the u t s - n e z 2012 Olympic Games to be held in London, we hope to see you there ! . w w w y b n g i s e D w w w . g y m n o v a . c o m FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE GYMNASTIQUE FONDÉE EN 1881 BULLETIN N° 218 Avril / April 2011 Organe officiel de la Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique. Trois éditions par année. Editeur: FIG. Rédacteur: André F. GUEISBUHLER, Secrétaire Général. Réalisation: FIG. Le Bulletin FIG est une publication officielle éditée par la FIG depuis 1953. --- Official publication of the International Gymnastics Federation. Three issues per year. Publisher: FIG. Editor: André F. GUEISBUHLER, Secretary General. Lay out: FIG. FIG Bulletin is an official publication issued by the FIG since 1953. Adresse officielle: FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE Official address: DE GYMNASTIQUE 12, Avenue de la Gare 1003 LAUSANNE / Switzerland Phone: +41.21.321.55.10 Fax: +41.21.321.55.19 [email protected] www.fig-gymnastics.com 1 Bulletin N° 218 April 2011 SOMMAIRE – CONTENT MAGAZINE Français English Calendrier FIG / FIG calendar 5 5 Fournisseurs détenteurs du certificat FIG / Suppliers holders of the FIG certificate 7 7 HOMMAGE / TRIBUTE Nikolaï Andrianov passed -

News: 2007 National Team List

News: 2007 National Team List | USAG HOME | NEWS | EVENTS | USA Gymnastics 2006-07 U.S. National Teams Updated 19-Feb-07 NOTE: Teams were named at the conclusion of the 2006 Visa Championships. The men's team list was updated at the conclusion of the 2007 Winter Cup Challenge (Feb.07). Trampoline and tumbling will name its national team in early 2007. Women's artistic gymnastics Senior ● Jana Bieger, Coconut Creek, Fla./Boca Twisters ● Kayla Hoffman, Union, N.J./Rebound ● Jacquelyn Johnson, Westchester, Ohio/Cincinnati Gymnastics ● Natasha Kelley, Katy, Texas/Stars Houston ● Nastia Liukin, Parker, Texas/WOGA ● Chellsie Memmel, West Allis, Wis./M&M ● Christine Nguyen, Plano, Texas/WOGA ● Kassi Price, Plantation, Fla./Orlando Metro ● Ashley Priess, Hamilton, Ohio/Cincinnati Gymnastics ● Alicia Sacramone, Winchester, Mass./Brestyan's ● Randi Stageberg, Chesapeake, Va./Excalibur ● Amber Trani, Richland, Pa./Parkettes ● Shayla Worley, Orlando, Fla./Orlando Metro Junior ● Rebecca Bross, Ann Arbor, Mich./WOGA ● Sarah DeMeo, Overland Park, Kansas/GAGE ● Bianca Flohr, Creston, Ohio/Cincinnati Gymnastics ● Ivana Hong, Laguna Hills, Calif./GAGE ● Shawn Johnson, Des Moines, Iowa/Chow's ● Corrie Lothrop, Gaithersburg, Md./Hill's ● Catherine Nguyen, Plano, Texas/WOGA ● Shantessa Pama, Dana Point, Calif./Gym Max ● Samantha Peszek, McCordsville, Ind./DeVeau's ● Samantha Shapiro, Los Angeles/All Olympia ● Bridget Sloan, Pittsboro, Ind./Sharp's ● Rachel Updike, Overland Park, Kan./GAGE ● Cassie Whitcomb, Cincinnati, Ohio/Cincinnati Gymnastics ● Jordyn Wieber, -

Retired Female Gymnasts' Reflections on Body Image and Sense of Self Briley Casanova [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 8-6-2019 Retired Female Gymnasts' Reflections on Body Image and Sense of Self Briley Casanova [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Casanova, Briley, "Retired Female Gymnasts' Reflections on Body Image and Sense of Self" (2019). LSU Master's Theses. 4993. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4993 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETIRED FEMALE GYMNASTS’ REFLECTIONS ON BODY IMAGE AND SENSE OF SELF A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Kinesiology by Briley Casanova B.A., University of Michigan, 2016 December 2019 Acknowledgements I want to sincerely thank my advisor and committee member Dr. Alex Garn for his incredible support and guidance throughout the thesis writing process. He has been an exceptional instructor, leader and mentor throughout my time at LSU. I also thank my other committee members and professors, Dr. Melinda Solmon, Dr. Amanda Benson and Dr. Elizabeth “Kip” Webster for their endless support and feedback. This project would not have come to fruition without the unconditional love and encouragement from my parents Bev and Zelda, my brother Cole and the entirety of my family and friends. -

Official Race Results

NASCAR NATIONWIDE SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 8 22ND ANNUAL AARON'S 312 TALLADEGA SUPERSPEEDWAY Talladega, AL - May 4, 2013 2.66-Mile Paved Tri-Oval 117 Laps - 311.22 Miles Purse: $1,200,772 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 11 minutes, 44 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 133.269 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: Under Caution Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 20 7 Regan Smith TaxSlayer.com Chevrolet 110 47 4 112.6 $53,445 Running 6 7 2 12 22 Joey Logano (i) Discount Tire Ford 110 0 132.9 39,725 Running 9 35 3 11 5 Kasey Kahne (i) Great Clips Chevrolet 110 0 121.9 30,500 Running 9 16 4 9 1 Kurt Busch (i) Phoenix Construction Chevrolet 110 0 103.2 29,275 Running 5 19 5 5 31 Justin Allgaier Brandt Chevrolet 110 40 1 99.5 34,550 Running 2 4 6 18 77 Parker Kligerman Camp Horsin' Around/Bandit Chippers Toyota 110 39 1 94.7 28,100 Running 3 4 7 38 01 Mike Wallace Chevrolet 110 37 70.3 26,500 Running 8 31 24 Jason White JW Demolition Toyota 110 36 61.7 25,850 Running 9 37 51 Jeremy Clements AllSouthElectric.com Chevrolet 110 35 69.0 25,225 Running 10 2 3 Austin Dillon AdvoCare Chevrolet 110 35 1 72.2 26,825 Running 1 5 11 7 11 Elliott Sadler OneMain Financial Toyota 110 34 1 97.5 25,975 Running 3 5 12 29 55 Jamie Dick Viva Auto Group Chevrolet 110 32 59.3 18,850 Running 13 14 99 Alex Bowman # SchoolTipline.com Toyota 110 31 88.1 25,675 Running 14 24 19 Mike Bliss Dixie Chopper Toyota 110 30 73.7 24,500 Running 15 21 20 Brian Vickers Dollar General Toyota 110 30 1 105.5 25,050 Running 1 1 16 27 79 Jeffrey Earnhardt -

RESULTS 400 Metres Women - Final

Moscow (RUS) World Championships 10-18 August 2013 RESULTS 400 Metres Women - Final RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE DATE VENUE World Record 47.60 Marita KOCH GDR 28 6 Oct 1985 Canberra Championships Record 47.99 Jarmila KRATOCHVÍLOVÁ TCH 32 10 Aug 1983 Helsinki World Leading 49.33 Amantle MONTSHO BOT 30 19 Jul 2013 Monaco TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY START TIME 21:18 21° C 60 % Final 12 August 2013 PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH LANE RESULT REACTION Fn 1 379 Christine OHURUOGU GBR 17 May 84 4 49.41 NR 0.247 Кристин Охуруогу 17 мая 84 2 170 Amantle MONTSHO BOT 04 Jul 83 5 49.41 0.273 Амантле Монтшо 04 июля 83 3 735 Antonina KRIVOSHAPKA RUS 21 Jul 87 8 49.78 0.209 Антонина Кривошапка 21 июля 87 4 518 Stephanie MCPHERSON JAM 25 Nov 88 2 49.99 0.198 Стефани МакФерсон 25 нояб . 88 5 916 Natasha HASTINGS USA 23 Jul 86 3 50.30 0.163 Наташа Хастингс 23 июля 86 6 930 Francena MCCORORY USA 20 Oct 88 6 50.68 0.241 Франчена МакКорори 20 окт . 88 7 751 Kseniya RYZHOVA RUS 19 Apr 87 7 50.98 0.195 Ксения Рыжова 19 апр . 87 8 514 Novlene WILLIAMS-MILLS JAM 26 Apr 82 1 51.49 0.276 Новлин Уильямс -Миллс 26 апр . 82 ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT NAME Venue DATE RESULT NAME Venue DATE 47.60 Marita KOCH (GDR) Canberra 6 Oct 85 49.33 Amantle MONTSHO (BOT) Monaco 19 Jul 13 47.99 Jarmila KRATOCHVÍLOVÁ (TCH) Helsinki 10 Aug 83 49.41 Christine OHURUOGU (GBR) Moscow 12 Aug 13 48.25 Marie-José PÉREC (FRA) Atlanta, GA 29 Jul 96 49.57 Antonina KRIVOSHAPKA (RUS) Moskva 15 Jul 13 48.27 Olga VLADYKINA-BRYZGINA (UKR) Canberra 6 Oct 85 49.80 Kseniya RYZHOVA (RUS) Cheboksary -

Kids-Guide-To-The-Olympic-Games-Sample.Pdf

kidskidsproudly guideguide presents TOTO THETHE TOKYOTOKYO OLYMPICSOLYMPICS watch all of the action on the networks of To download the rest of the guide, visit www.sportsengine.com/kids-guide kidskids guideguide TOTO THETHE TOKYOTOKYO OLYMPICSOLYMPICS kidskids guideguide TOTO THETHE TOKYOTOKYO OLYMPICSOLYMPICS SportsEngine, a division of NBC Sports Digital & Consumer Business Minneapolis, MN The author wishes to thank Megan Soisson, Sarah Hughes, Andrew Dougherty, and the rest of the NBC Sports Olympic researchers who provided invaluable fact-checking for hundreds of individual Olympic and historical facts. Without their support, this guide would not have been possible. A special thanks to all of the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee and the national governing bodies who provided content for this guide. Concepted & Written by Rob Bedeaux Designed by Dawn Fifer & Morgan Ramthun Production art by Cali Schimberg & Keaton McAuliffe Copyright © 2021 by SportsEngine, a division of NBC Sports Digital & Consumer Businesses All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the copyright owner. Contents 1 Overview of the Olympic Games Cycling .......................................................37 Table Tennis .............................................79 Ancient Games .......................................... 1 Diving .........................................................39 Taekwondo ...............................................81 Modern Games ........................................ -

2017 Hockey Career Conference at the NHL Draft Chicago, Illinois

2017 Hockey Career “To Catch a Foul Ball Conference at the You Need a Ticket to the Game” NHL Draft - Dr. G. Lynn Lashbrook Chicago, Illinois JUNE 22-24, 2017 The Global Leader in Sports Education | SMWW.com | 1-877-SMWW-Now NHL CAREER CONFERENCE AGENDA SMWW SUCCESS STORIES Thursday, June 22 Over 15,000 graduates working in over a 140 countries! Alexa Atria, New York Yankees Michael Gershon Keystone Ice Miners Brian Orth, Cloverdale Minor Hockey Association 7pm-9pm John Ross, Portland Trail Blazers Travis Gibson Champion Hockey Brian Gioia, Chicago Bulls Simon Barrette Columbus Blue Jackets Frank Gilberti Chatham High School Brian Adams, Boston Celtics Chicago Sports Museum Mark Warkentien, New York Knicks Bob Gillen Yellowstone Quake Chad Pennick, Denver Nuggets Come network with hockey executives, SMWW Staff and other hockey conference Paul Epstein, San Francisco 49ers Jessica Gillis Hockey New Brunswick Chris Cordero, Miami Heat attendees. Held at Chicago Sports Museum, just half mile from the Chicago Demetri Betzios, Toronto Argonauts Tony Griffo London Knights Christian Alicpala, Toronto Raptors 835 N Michigan Ave, Andre Sherard, Sporting Kansas City Mario Guido Rinknet Christian Stoltz, USAL Rugby Marriott Hotel, the welcome reception is always a great time. Everyone there is Taylore Scott, Dallas Cowboys Brian Guindon HockeyTwentyFourSeven Christian Payne, Dickinson College Chicago, IL 60611 excited about the career conference, learning from each other and sharing a few Alireza Absalan, FIFA Agent Aaron Guli President Irish Ice -

MEET INFORMATION GATOR SOCIAL DID YOU KNOW MEET 2 BATON ROUGE, LA. What's Happening?

3 NCAA Championships ● 10 SEC Championships ● 8 with 19 NCAA Individual Titles MEET INFORMATION MEET 2 BATON ROUGE, LA. Date: Friday, Jan. 18 / 9 p.m. ET No. 3 Florida Gators No. 5 LSU Tigers Site: Pete Maravich Assembly Center (13,200) Head Coach: Jenny Rowland Head Coach: D-D Breaux Television: SEC Network Career (4th season): 43-9 Career (42nd season): 774-424-8 Video: WatchESPN At UF: same At LSU: same Live Stats: FloridaGators.com Tickets: Range in price from $12-$6. Contact LSU 2019: 1-0 / 1-0 SEC 2019: 1-1 / 0-1 SEC Ticket Office at (225) 578-2184 for more 2018 NCAA Finish: 3rd 2018 NCAA Finish: 4th information Series Record UF leads 70-40 (last meeting: UF was third (all-time): in 2018 NCAA Super Six (197.85) and What’s Happening? LSU was fourth (197.8375) Florida continues action versus Southeastern Conference “Tigers” when the Gators travel to No. 5 LSU. This is the 21st consecutive meeting both teams bring top-10 rankings. Meetings between these two teams are traditionally close. Of the GATOR SOCIAL last 20 meetings, less than a half a point was the deciding margin 17 times. Florida Gators Gymnastics The Florida-LSU dual ends the first-ever SEC Network Friday Night Heights triple-header. Olympic medalists Bart Conner Florida Gators and Kathy Johnson Clarke call the action Friday beginning at 9 p.m. @GatorsGym @FloridaGators Florida used its highest opening total (and the nation’s second-highest 2019 opening score) to take a 197.30-196.45 win over No. -

IJURCA: International Journal of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activities

IJURCA: International Journal of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activities Volume 12.2 Article 7 September 3, 2020 Impact of professional women athletes’ media representations on collegiate women athletes Rae Martinez Pacific University, [email protected] Jennifer Bhalla, PhD Pacific University, [email protected] Abstract There is a lack of representation of women athletes from professional to collegiate sports in U.S. media. For example, Fink (2015) studied the inequities between male and women athletes to understand the harmful nature of the implication of these inequities. Other social constructs arise with the objectification of women athletes. Harrison and Fredrickson (2013) found a connection between aging of adolescent girls to women and an increase of self-objectification. They explained their results using Objectification Theory, which teaches young women to “regard themselves in an objectified gaze” from adolescence. The purpose of this study was to examine women collegiate athletes’ thoughts and feelings about the ways their elite representatives are presented within sports media. Women collegiate athletes viewed images displaying four different types of identity portrayals, and were then interviewed about their perceptions of the images. Each participant asked to answer five questions, and that data was analyzed using open coding methods. Keywords Women athletes, Media representation, Higher education, College Peer Review This work has undergone a double-blind review by a minimum of two faculty members from institutions of higher learning from around the world. The faculty reviewers have expertise in disciplines closely related to those represented by this work. If possible, the work was also reviewed by undergraduates in collaboration with the faculty reviewers.