Prefatory Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity Presents

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity presents Friday Film Series 2012-2013: Exploring Social Justice Through Film All films begin at 12:00 pm on the Chicago campus. Due to the length of most features, we begin promptly at noon! All films screened in Daniel Hale Williams Auditorium, McGaw Pavilion. Lunch provided for attendees. September 14 – Reel Injun by Neil Diamond (Cree) http://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/ Reel Injun is an entertaining and insightful look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema. Travelling through the heartland of America and into the Canadian North, Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond looks at how the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding – and misunderstanding – of Natives. With clips from hundreds of classic and recent films, and candid interviews with celebrated Native and non-Native directors, writers, actors, and activists including Clint Eastwood, Robbie Robertson, Graham Greene, Adam Beach, and Zacharias Kunuk, Reel Injun traces the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to present day. October 19 – Becoming Chaz by Fenton Bailey & Randy Barbato http://www.chazbono.net/becomingchaz.html Growing up with famous parents, constantly in the public eye would be hard for anyone. Now imagine that all those images people have seen of you are lies about how you actually felt. Chaz Bono grew up as Sonny and Cher’s adorable golden-haired daughter and felt trapped in a female shell. Becoming Chaz is a bracingly intimate portrait of a person in transition and the relationships that must evolve with him. -

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1

45477 ACTRA 8/31/06 9:50 AM Page 1 Summer 2006 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists ACTION! Production coast to coast 2006 SEE PAGE 7 45477 ACTRA 9/1/06 1:53 PM Page 2 by Richard We are cut from strong cloth Hardacre he message I hear consistently from fellow performers is that renegotiate our Independent Production Agreement (IPA). Tutmost on their minds are real opportunities for work, and We will be drawing on the vigour shown by the members of UBCP proper and respectful remuneration for their performances as skilled as we go into what might be our toughest round of negotiations yet. professionals. I concur with those goals. I share the ambitions and And we will be drawing on the total support of our entire member- values of many working performers. Those goals seem self-evident, ship. I firmly believe that Canadian performers coast-to-coast are cut even simple. But in reality they are challenging, especially leading from the same strong cloth. Our solidarity will give us the strength up to negotiations of the major contracts that we have with the we need, when, following the lead of our brothers and sisters in B.C. associations representing the producers of film and television. we stand up and say “No. Our skill and our work are no less valuable Over the past few months I have been encouraged and inspired than that of anyone else. We will be treated with the respect we by the determination of our members in British Columbia as they deserve.” confronted offensive demands from the big Hollywood companies I can tell you that our team of performers on the negotiating com- during negotiations to renew their Master Agreement. -

PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] Visit the PBS pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: http://www.pbs.org/pressroom/ PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour A Provocative and Entertaining Look at the Portrayal of Native Americans in Cinema to Air November 2010 During Native American Heritage Month (San Francisco, CA)—Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond takes an entertaining, insightful, and often humorous look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema and examining the ways that the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding—and misunderstanding—of Natives. Narrated by Diamond with infectious enthusiasm and good humor, Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian is a loving look at cinema through the eyes of the people who appeared in its very first flickering images and have survived to tell their stories their own way. Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian will air nationally on the upcoming season of the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens in November 2010. Tracing the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to today, Diamond takes the audience on a journey across America to some of cinema’s most iconic landscapes, including Monument Valley, the setting for Hollywood’s greatest Westerns, and the Black Hills of South Dakota, home to Crazy Horse and countless movie legends. -

March 2018 New Releases

March 2018 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 59 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 8 RICHIE KOTZEN - TONY MACALPINE - RANDY BRECKER QUINTET - FEATURED RELEASES TELECASTERS & DEATH OF ROSES LIVEAT SWEET BASIL 1988 STRATOCASTERS: Music Video KLASSIC KOTZEN DVD & Blu-ray 35 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 39 Order Form 65 Deletions and Price Changes 63 800.888.0486 THE SOULTANGLER KILLER KLOWNS FROM BRUCE’S DEADLY OUTER SPACE FINGERS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 [BLU-RAY + DVD] DWARVES & THE SLOTHS - DUNCAN REID & THE BIG HEADS - FREEDOM HAWK - www.MVDb2b.com DWARVES MEET THE SLOTHS C’MON JOSEPHINE BEAST REMAINS SPLIT 7 INCH March Into Madness! MVD offers up a crazy batch of March releases, beginning with KILLER KLOWNS FROM OUTER SPACE! An alien invasion with a circus tent for a spaceship and Killer Klowns for inhabitants! These homicidal clowns are no laughing matter! Arrow Video’s exclusive deluxe treatment comes with loads of extras and a 4K restoration that will provide enough eye and ear candy to drive you insane! The derangement continues with HELL’S KITTY, starring a possessed cat who cramps the style of its owner, who is beginning a romantic relationship. Call a cat exorcist, because this fiery feline will do anything from letting its master get some pu---! THE BUTCHERING finds a serial killer returning to a small town for unfinished business. What a cut-up! The King of Creepy, CHRISTOPHER LEE, stars in the 1960 film CITY OF THE DEAD, given new life with the remastered treatment. -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. APPROVAL NAME Diane Louise Burgess DEGREE PhD TITLE OF DISSERTATION: Negotiating Value: A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival EXAMINING COMMITTEE: CHAIR: Barry Truax, Professor Catherine Murray Senior Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Zoe Druick Supervisor Associate Professor, School of Communication Alison Beale Supervisor Professor, School of Communication Stuart Poyntz, Internal Examiner Assistant Professor, School of Communication Charles R Acland, Professor, Communication Studies Concordia University DATE: September 18, 2008 11 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

A Canadian Perspective on the International Film Festival

NEGOTIATING VALUE: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE ON THE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL by Diane Louise Burgess M.A., University ofBritish Columbia, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the School ofCommunication © Diane Louise Burgess 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission ofthe author. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58719-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. -

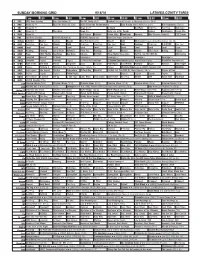

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Northern Review 43 Fall 2016.Indd

Exploring human experience in the North research arƟ cle “Indigenizing” the Bush Pilot in CBC’s ArcƟ c Air Renée Hulan Saint Mary’s University, Halifax Abstract When the Canadian BroadcasƟ ng CorporaƟ on (CBC) cut original programming in 2014, it cancelled the drama that had earned the network’s highest raƟ ngs in over a decade. Arc c Air, based on Omni Films’ reality TV show Buff alo Air, created a diverse cast of characters around a Dene bush pilot and airline co-owner played by Adam Beach. Despite its cancellaƟ on, episodes can sƟ ll be viewed on the CBC website, and the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) has conƟ nued broadcasƟ ng the popular show. Through a content analysis of Arc c Air and its associated paratext, read in relaƟ on to the stock Canadian literary fi gure of the heroic bush pilot, this arƟ cle argues that when viewed on the CBC, the program visually “Indigenizes” the bush pilot character, but suggests only one way forward for Indigenous people. On the “naƟ onal broadcaster,” the imagined urban, mulƟ cultural North of Arc c Air—in which Indigenous people are one cultural group among others parƟ cipaƟ ng in commercial ventures—serves to normalize resource development and extracƟ on. Broadcast on APTN, however, where the show appears in the context of programming that represents Indigenous people in a wide range of roles, genres, and scenarios, Arc c Air takes on new meaning. Keywords: media; television; Canadian North; content analysis The Northern Review 43 (2016): 139–162 Published by Yukon College, Whitehorse, Canada yukoncollege.yk.ca/review 139 In 2013, the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) lost the broadcast rights to Hockey Night in Canada, a contract that the private broadcaster Rogers Media secured for $5.2 billion. -

Maailman Elokuvan Historia III

Maailman elokuvan historia III Kanada, Australia, Uusi Seelanti Kanada: puitteet • Canadian Pacific Railroad:n tuottamia dokumentteja • Tarinaelokuva pääasiassa USA:sta, osa UK:sta • Ensimmäinen oma tarinaelokuva, Evangeline (1913) oli sekä kriittinen että yleisömenestys, mutta seuraavat elokuvat eivät olleet → tuottajayhtiö lopetti 1915 • Hieman tuotantoa 1920-luvulla, mutta äänielokuvan läpimurto tyrehdytti taas tuotannon • Docudraamoja ja muita tarinaa ja dokumentaaria sekoittavia lajityyppejä • Tarinaelokuva rajoittui pitkään "quota quickies” - tuotantoon National Film Board of Canada perustettiin 1939 Canadian Co-operation Project (1948-58) Luovat lahjakkuudet emigroituivat Hollywoodin tai UK:an Canadian Film Development Corporation perustetaan 1967 koordinoimaan investointeja, lainoja ja tukia Taloudelliset kannustimet ja verohelpotukset 1974 alkaen lisäävät massiivisesti sijoittamista Kanadalaiseen tuotantoon ”Tax-shelter era” johtaa pian kulttuurielokuvista suuren budjetin tuotantoihin National Film & Video Policy heijastaa taiteellisesti kunnianhimoisempaa suuntausta, mutta myös television roolia julkaisukanavana – CFDC:stä tulee Telefilm Canada Pienen budjetin itsenäistä tuotantoa syntyy kaikissa provinsseissa ja territorioissa Canadian Film Centre (CFC) perustetaan 1988 – osa rahoitusta hankitaan ei-valtiollisista lähteistä 1980-90 luvuilla ohjaajat kuten Denys Arcand, Patricia Rozema ja Gail Singer sekä maahanmuuttajat kuten Atom Egoyan (Egypt) ja Deepa Mehta (Intia) tekevät kv. läpimurtonsa ”Toronto New Wave” Kanadan -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada's Feature Film Policy Since

Media Industries 4.2 (2017) DOI: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.204 Bureaucrats and Movie Czars: Canada’s Feature Film Policy since 20001 Charles Tepperman2 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY c.tepperman [AT] ucalgary.ca Abstract: This essay provides a case study of one nation’s efforts to defend its culture from the influx of Hollywood films through largely bureaucratic means and focused on the increasingly outdated metric of domestic box-office performance. Throughout the early 2000s, Canadian films accounted for only around 1 percent of Canada’s English-language market, and were seen by policy makers as a perpetual “problem” that needed to be fixed. Similar to challenges found in most film-producing countries, these issues were navigated very differently in Canada. This period saw the introduction of a new market-based but cultural “defense” oriented approach to Canadian film policy. Keywords: Film Policy, Production, Canada Introduction For over a century, nearly every film-producing nation has faced the challenge of competing with Hollywood for a share of its domestic box office. How to respond to the overwhelming flood of expensively produced and slickly marketed films that capture most of a nation’s eye- balls? One need not be a cultural elitist or anti-American to point out that the significant presence of Hollywood films (in most countries more than 80 percent) can severely restrict the range of films available and create barriers to the creation and dissemination of home- grown content.3 Diana Crane notes that even as individual nations employ cultural policies to develop their film industries, these efforts “do not provide the means for resisting American domination of the global film market.”4 In countries like Canada, where the government plays a significant role in supporting the domestic film industry, these challenges have political and Media Industries 4.2 (2017) policy implications.