Impressionism8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prints from Private Collections in New England, 9 June – 10 September 1939, No

Bernardo Bellotto (Venice 1721 - Warsaw 1780) The Courtyard of the Fortress of Königstein with the Magdalenenburg oil on canvas 49.7 x 80.3 cm (19 ⁵/ x 31 ⁵/ inches) Bernardo Bellotto was the nephew of the celebrated Venetian view painter Canaletto, whose studio he entered around 1735. He so thoroughly assimilated the older painter’s methods and style that the problem of attributing certain works to one painter or the other continues to the present day. Bellotto’s youthful paintings exhibit a high standard of execution and handling, however, by about 1740 the intense effects of light, shade, and color in his works anticipate his distinctive mature style and eventual divergence from the manner of his teacher. His first incontestable works are those he created during his Italian travels in the 1740s. In the period 1743-47 Bellotto traveled throughout Italy, first in central Italy and later in Lombardy, Piedmont, and Verona. For many, the Italian veduteare among his finest works, but it was in the north of Europe that he enjoyed his greatest success and forged his reputation. In July 1747, in response to an official invitation from the court of Dresden, Bellotto left Venice forever. From the moment of his arrival in the Saxon capital, he was engaged in the service of Augustus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, and of his powerful prime minister, Count Heinrich von Brühl. In 1748 the title of Court Painter was officially conferred on the artist, and his annual salary was the highest ever paid by the king to a painter. -

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011

Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM Last updated Friday, February 11, 2011 Updated Friday, February 11, 2011 | 3:41:22 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Venice: Canaletto and His Rivals February 20, 2011 - May 30, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. File Name: 2866-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw File Name: 2866-103.jpg Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia (Iconongraphic Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 Display Order Representation of the Illustrious City of Venice), 1729 etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper etching and engraving on twenty joined sheets of laid paper 148.5 x 264.2 -

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800

Gallery Painting in Italy, 1700-1800 The death of Gian Gastone de’ Medici, the last Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany, in 1737, signaled the end of the dynasties that had dominated the Italian political landscape since the Renaissance. Florence, Milan, and other cities fell under foreign rule. Venice remained an independent republic and became a cultural epicenter, due in part to foreign patronage and trade. Like their French contemporaries, Italian artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Francesco Guardi, and Canaletto, favored lighter colors and a fluid, almost impressionistic handling of paint. Excavations at the ancient sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii spurred a flood of interest in classical art, and inspired new categories of painting, including vedute or topographical views, and capricci, which were largely imaginary depictions of the urban and rural landscape, often featuring ruins. Giovanni Paolo Pannini’s paintings showcased ancient and modern architectural settings in the spirit of the engraver, Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Music and theater flourished with the popularity of the piano and the theatrical arts. The commedia dell’arte, an improvisational comedy act with stock characters like Harlequin and Pulcinella, provided comic relief in the years before the Napoleonic War, and fueled the production of Italian genre painting, with its unpretentious scenes from every day life. The Docent Collections Handbook 2007 Edition Francesco Solimena Italian, 1657-1747, active in Naples The Virgin Receiving St. Louis Gonzaga, c. 1720 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 165 Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini Italian, 1675-1741, active in Venice The Entombment, 1719 Oil on canvas Bequest of John Ringling, 1936, SN 176 Amid the rise of such varieties of painting as landscape and genre scenes, which previously had been considered minor categories in academic circles, history painting continued to be lauded as the loftiest genre. -

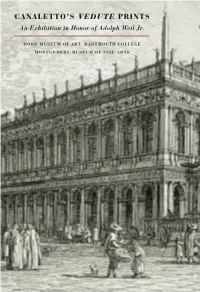

Canaletto's Vedute Prints

CANALETTO’S VEDUTE PRINTS An Exhibition in Honor of Adolph Weil Jr. HOOD MUSEUM OF ART, DARTMOUTH COLLEGE MONTGOMERY MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 153064_Canaletto.indd 1 12/2/14 2:18 PM INTRODUCTION Mark M. Johnson, Director, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts Michael R. Taylor, Director, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College he Hood Museum of Art and the actual sites and imaginary vistas, and at times Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts are even interweaving the familiar with the fantas- Tdelighted to present Canaletto’s Vedute tic. Through these prints, Canaletto revealed Prints: An Exhibition in Honor of Adolph an unseen Venice to what he hoped would be Weil Jr. This partnership reflects the indelible a new audience and a new market: collectors imprint that this remarkable collector’s legacy spurred by the revival of printmaking in has borne on the museums of his hometown, eighteenth-century Italy. The results of his Montgomery, Alabama, and of his alma mater, project were unexpected and revelatory, and as Dartmouth College, which he attended from magical today as in Canaletto’s own time. 1931 to 1935. Both the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts and the Hood Museum of Art have in the past mounted exhibitions of Mr. Weil’s prints that are now held by the institutions. In this collaborative venture, we celebrate another important aspect of Mr. Weil’s outstanding collection, Canaletto’s magnificent etchings of eighteenth-century Venice. This project was planned jointly to commemorate the one hun- dredth anniversary of the birth of the donor, and to celebrate his vision and dedication as a collector of Old Master prints. -

Perspective on Canaletto's Paintings of Piazza San Marco in Venice

Art & Perception 8 (2020) 49–67 Perspective on Canaletto’s Paintings of Piazza San Marco in Venice Casper J. Erkelens Experimental Psychology, Helmholtz Institute, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 21 June 2019; accepted 18 December 2019 Abstract Perspective plays an important role in the creation and appreciation of depth on paper and canvas. Paintings of extant scenes are interesting objects for studying perspective, because such paintings provide insight into how painters apply different aspects of perspective in creating highly admired paintings. In this regard the paintings of the Piazza San Marco in Venice by Canaletto in the eigh- teenth century are of particular interest because of the Piazza’s extraordinary geometry, and the fact that Canaletto produced a number of paintings from similar but not identical viewing positions throughout his career. Canaletto is generally regarded as a great master of linear perspective. Analysis of nine paintings shows that Canaletto almost perfectly constructed perspective lines and vanishing points in his paintings. Accurate reconstruction is virtually impossible from observation alone be- cause of the irregular quadrilateral shape of the Piazza. Use of constructive tools is discussed. The geometry of Piazza San Marco is misjudged in three paintings, questioning their authenticity. Sizes of buildings and human figures deviate from the rules of linear perspective in many of the analysed paintings. Shadows are stereotypical in all and even impossible in two of the analysed paintings. The precise perspective lines and vanishing points in combination with the variety of sizes for buildings and human figures may provide insight in the employed production method and the perceptual experi- ence of a given scene. -

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European Art of the Eighteenth Century Increasingly Emphasized Civility, Elegance, Comfor

The Age of Pleasure and Enlightenment European art of the eighteenth century increasingly emphasized civility, elegance, comfort, and informality. During the first half of the century, the Rococo style of art and decoration, characterized by lightness, grace, playfulness, and intimacy, spread throughout Europe. Painters turned to lighthearted subjects, including inventive pastoral landscapes, scenic vistas of popular tourist sites, and genre subjects—scenes of everyday life. Mythology became a vehicle for the expression of pleasure rather than a means of revealing hidden truths. Porcelain and silver makers designed exuberant fantasies for use or as pure decoration to complement newly remodeled interiors conducive to entertainment and pleasure. As the century progressed, artists increasingly adopted more serious subject matter, often taken from classical history, and a simpler, less decorative style. This was the Age of Enlightenment, when writers and philosophers came to believe that moral, intellectual, and social reform was possible through the acquisition of knowledge and the power of reason. The Grand Tour, a means of personal enlightenment and an essential element of an upper-class education, was symbolic of this age of reason. The installation highlights the museum’s rich collection of eighteenth-century paintings and decorative arts. It is organized around four themes: Myth and Religion, Patrons and Collectors, Everyday Life, and The Natural World. These themes are common to art from different cultures and eras, and reveal connections among the many ways artists have visually expressed their cultural, spiritual, political, material, and social values. Myth and Religion Mythological and religious stories have been the subject of visual art throughout time. -

Let's Make a Scene!

Let’s Make a Scene! The Holburne welcomes Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto, who was born in Venice, the son of a theatrical scene painter. His father was Bernardo Canal, hence his son being know as Canaletto meaning “little Canal". During his life Bernardo Canal was best known as a painter of theatrical sets for works by composers Antonio Vivaldi, Fortunato Chelleri, Carlo Francesco Pollarolo and Giuseppe Maria Orlandini at two popular Venetian Theatres. Canaletto popularised veduta, which means a highly detailed, usually large-scale, painting of a cityscape or some other vista. You can see how these beautiful veduta, or city- scapes, easily inspire and translate into stage sets like this reconstruction of the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice, with each layer unfolding like a diorama. The Activity To make a 'Scene in a Tin', tub or box like a miniature stage set of a Venetian veduta. Take inspiration from the theatres and streets of Canaletto's Venice and layer your scene to create a 3D effect. Activity Sheet designed by Susie Walker What will you need? • A tub, tin or box to build your scene in. • Thin card and thick card (stiffer like packaging card) • Pencil and ruler • Scissors &/or craft knife • Glue • Colours for decorating paper • Black pen for outlining detail How to make your scene 1. Prepare your clean tub and decide what your scene will be - Venice; Bath; the sea; a fairy tale even. Collect some images to inspire you. 2. Paint some small pieces of thin card in the colours you would like to use for your scene. -

Bernardo Bellotto (Venice 1721-1780 Warsaw)

PROPERTY FROM A DISTINGUISHED PRIVATE COLLECTION ■9 BERNARDO BELLOTTO (VENICE 1721-1780 WARSAW) View of Verona with the Ponte delle Navi oil on canvas 52q x 92q in. (133.3 x 234.8 cm.) painted in 1745-47 £12,000,000-18,000,000 US$18,000,000-26,000,000 €14,000,000-21,000,000 PROVENANCE: LITERATURE: Anonymous sale ‘lately consigned from abroad’; Christie’s, 30 March [=2nd M. Chamot, ‘Baroque Paintings’, Country Life, LX, 6 November 1926, p. 708. day] 1771, lot 55, as 'Canaletti', 'its companion [lot 54; A large and most capital A. Oswald, ‘North Mymms Park, II’, Country Life, LXXV, 20 January 1934, picture, being a remarkable view of the city of Verona, on the banks of the pp. 70-1, fig. 13. Adige. This picture is finely coloured, the perspective, its light and shadow S. Kozakiewicz, in Bernardo Bellotto 1720-1780, Paintings and Drawings from fine and uncommonly high finish’d’; 250 guineas to Grey] exhibiting another the National Museum of Warsaw, exhibition catalogue, London, Whitechapel view of the same city, equally fine, clear and transparent’, the measurements Art Gallery, Liverpool, York and Rotterdam (catalogue in Dutch), 1957, p. 25, recorded as 53 by 90 inches (250 guineas to ‘Fleming’, ie. the following). under no. 32. Gilbert Fane Fleming (1724-1776), Marylebone; Christie’s, London, 22 May W. Schumann and S. Kozakiewicz, in Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto 1777, as ‘Canaletti. A view of the city of Verona, esteemed the chef d’œuvre of in Dresden und Warschau, exhibition catalogue, Dresden, 1963, respectively the master’ (205 guineas to ‘Ld Cadogan’, i.e. -

ANTONIO CANALETTO, Basin of San Marco from San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice Ca

Both the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution began in the eighteenth century, and with them came the dominance of modern science. The Enlightenment Enlightenment (or “Age of Reason”): A movement in 18th century thought. Its central idea was the need for (and the capacity of) human reason to clear away ancient superstition, prejudice, dogma, and injustice. Enlightenment thinking encouraged rational scientific inquiry, humanitarian tolerance, and the idea of universal human rights. These thoughts mobilized a widespread dissatisfaction with contemporary social and political ills, and culminated with the American (1774-1783) and French (1789–1799) Revolutions. 3:31 – John Locke and Voltaire http://youtu.be/K7q5oT-X_PI Neoclassicism: mid 18th - mid 19th c. Relating to, or constituting a revival or adaptation of the classical style. It originated as a reaction to the Baroque and the sensuous and decorative Rococo style . Neoclassicism sought to revive the ideals of ancient Greek and Roman art. Neoclassic artists used classical forms to express their ideas about courage, sacrifice, and love of their country. Jacques-Louis David , Oath of the Horatii. 1784 The Grand Tour: The enlightenment had made knowledge of ancient Rome and Greece imperative, and a steady stream of Europeans and Americans traveled to major sites of southern Europe, especially Italy, in the 18th and early 19th c. ANTONIO CANALETTO, Basin of San Marco from San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice ca. 1740. Oil on canvas. The Wallace Collection, London. Louise-Elisabeth Vigée- Lebrun. Portrait of Queen The French Revolution (1789–1799) Marie Antoinette with Children. Movement that shook France between 1787 and 1799, reaching its first climax in 1789, and ended the ancien régime (French: “old order”) The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is one of the fundamental documents of the French Revolution, defining a set of individual rights and collective rights Louis XVI, King of of the people. -

The Magical Light of Venice

The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings The Magical Light of Venice Eighteenth Century View Paintings Lampronti Gallery - London 30 November 2017 - 15 January 2018 10.00 - 18.00 pm Catalogue edited by Acknowledgements Marcella di Martino Alexandra Concordia, Barbara Denipoti, the staff of Itaca Transport and staff of Simon Jones Superfright Photography Mauro Coen Matthew Hollow Designed and printed by De Stijl Art Publishing, Florence 2017 www.destijlpublishing.it LAMPRONTI GALLERY 44 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DD Via di San Giacomo 22 00187 Roma On the cover: [email protected] Giovanni Battista Cimaroli, The Celebrations for the Marriage of the Dauphin [email protected] of France with the Infanta Maria Teresa of Spain at the French Embassy in www.cesarelampronti.com Venice in 1745, detail. his exhibition brings together a fine selection of Vene- earlier models through their liveliness of vision and master- T tian cityscapes, romantic canals and quality of light ful execution. which have never been represented with greater sensitivity Later nineteenth-century painters such as Bison and Zanin or technical brilliance than during the wondrous years of reveal the profound influence that Canaletto and his rivals the eighteenth century. had upon future generations of artists. The culture of reci- The masters of vedutismo – Canaletto, Marieschi, Bellot- procity between the Italian Peninsula and England during to and Guardi – are all included here, represented by key the Grand Siècle, epitomised by the relationship between works that capture the essence and sheer splendour of Canaletto and Joseph Consul Smith, is a key aspect of the Venice. -

Dp Canaletto Anglais

PRESS RELEASE sous le haut patronage de la Ville de Venise CANALETTO À VENISE C’EST AU MUSÉE MAILLOL 19 SEPTEMBRE 2012 > 10 FÉVRIER 2013 billets coupe–file www.museemaillol.com m c 1 9 x 5 , 6 4 - e l i o t r u s e l i u H – 0 3 7 1 - 5 2 7 1 – ) l i a t é d ( o r a n r o C s i a l a P r e u d d i e s n e h u c v S e . n H a u – o r D e k a l l o t V e e © t u o l t a o S h P a l – e n d i l r e e u B q i l i u s z a n B e a e s L u – M o t e t h e l c i a l t n a a a C t t S i d e i l r a e l n a a g C e d o l i ä n o m t e n A G OUVERT TOUS LES JOURS DE 10H30 À 19H — NOCTURNE LE VENDREDI JUSQU’À 21H30 61, RUE DE GRENELLE 75007 PARIS — MÉTRO RUE DU BAC CONTENTS 1- PRESS RELEASE 3 2- COMMISSION AND SCIENTIFIC COMITTEE 5 3- EXTRACTS FROM THE CATALOGUE 6 4- NON-EXHAUSTIVE LIST OF WORKS 13 5- VISUAL DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE FOR THE MEDIA 19 6- PRACTICAL INFORMATION 22 PRESS CONTACTS MUSÉE MAILLOL AGENCE OBSERVATOIRE 59-61 rue de Grenelle 68 rue Pernety 75007 Paris 75014 Paris Claude Unger Céline Echinard 06 14 71 27 02 01 43 54 87 71 [email protected] [email protected] Elisabeth Apprédérisse www.observatoire.fr 01 42 22 57 25 [email protected] 2 1- PRESS RELEASE Under the patronage of The City of Venice MUSÉE MAILLOL CANALETTO IN VENICE 19 September 2012 -10 February 2013 The Musée Maillol pays homage to Venice with the first exhibition devoted exclusively to Canaletto’s Venetian works.