Land Use Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaceful Valley Ranch: D an Extended Narrative History I I I I

I IJ-72 ~·· I PEACEFUL VALLEY RANCH: D AN EXTENDED NARRATIVE HISTORY I I I I 1 • I,' I I Dori M. Penny I and Thomas K. Larson I Larson-Tibesar Associates 421 S. Cedar St. I Laramie, Wyoming 82070 I Submitted to United States Department of Interior National Park Service I B&WSca:ns l:.'heodore Roosevelt National Park Medora, North Dakota 58645 6 TEC~:~:!G.\L 1:::~~:.'.::~:-:-:1 c:::i-;-:::R c:: :\1ER s:.:;-;v;cz c::;1:~ , 0~/~ !~~~M April, 1993 l<ATIONAL PARK SERVICE I Submitted in partial fulfillment of Purchase Order PXl540-I-023 l; Larson-Tibesar Project 91 IO!la I ~ I I I I I I I I I I I I cover photo: ca. 1925 photo from Peaceful Valley Ranch, courtesy of Wally Owen, I Medora, North Dakota ,I I I ~ I I PREFACE STATEMENT I TO I PEACEFUL VALLEY RANCH: AN EXTENDED NARRATIVE HISTORY This report was prepared under contract with Larson-Tibesar Associates, Inc., with I generous financial support from the Theodore Roosevelt Nature and History Association. The contract also called for preparation of a National Register of Historic Places nomination for the I historic resources at Peaceful Valley Ranch. Subsequent to the contractor's submittals of these products, review comments required that some changes be made to the them. Most changes I were editorial in nature, with one exception: reviewers (in the regional office, the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Office, and the National Register of Historic Places) agreed that the It property did not meet National Register criteria for eligibility under Criteria B, which the contractor had argued in their report and nomination. -

Hlocation Hclassification Howner of Property

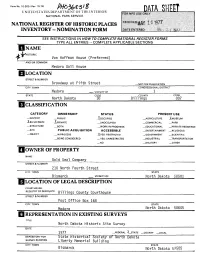

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) /T^D ""3/9 ft f3' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME Von Hoffman House (Preferred) AND/OR COMMON Medora Doll House HLOCATION STREET & NUMBER Broadway at Fifth Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Medora __ VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Dakota 38 Billings 007 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _D I STRICT —PUBLIC JlOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE _KMUSEUM -X-BUILDING(S) .X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS JCYES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: HOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Gold Seal Company STREET & NUMBER 210 North Fourth Street CITY, TOWN STATE Bismarck __ VICINITY OF North Dakota 58501 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDiyETc. Billings County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Post Office Box 168 CITY, TOWN STATE Medora North Dakota 58645 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS North Dakota Historic Site Survey DATE 1977 —FEDERAL X_STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR State Historical Society of North Dakota SURVEY RECORDS Liberty Memorial Building_________ CITY, TOWN STATE Bismarck North Dakota 53505 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^-ORIGINAL SITE -X.GOOD _RUINS -X.ALTERED MOVED DATF _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Von Hoffman House in Medora is a 1%-story, common-bond brick residence with a 5-course water table, a partial rock-walled basement, and an underground coal bin on the east elevation. -

1.0Purpose of and Need for Action

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Page 1 of 2) 1.0 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION ...................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 North Dakota CREP History ...................................................................... 2 1.3 Purpose and Need for Action ............................................................................... 3 1.4 Regulatory Compliance ........................................................................................ 6 1.5 Organization of the EA ......................................................................................... 7 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE ALTERNATIVES ..................................................................... 8 2.1 Alternative 1 – No Action ...................................................................................... 8 2.2 Alternative 2 – Proposed Action ........................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Objectives .................................................................................................. 8 2.2.2 Eligible Land .............................................................................................. 9 2.2.3 Proposed Conservation Practices ........................................................... 10 2.2.4 Financial Support to Land Owners -

You Are Invited E Work Hard to House for President Bush at Inside

You Are Invited e work hard to House for President Bush at Inside... Wpromote Medora the celebration of the 150th birthday of and invite people to Theodore Roosevelt in 2008. experience the North • All eighteen holes are open again at Bully Dakota Badlands. We Pulpit. 2 don’t do it as well as • The 18-month Von Hoffman house trmf chairman our customers: restoration is completed and ready for ed schafer “Seventeen years visitors! ago my husband and I • Kids will love the new stuff. An electronic took our first vacation western shooting gallery returns to Randy Hatzenbuhler together to Medora from downtown Medora; and the new “Family 3 TRMF President under harold’s Rapid City, SD. I told him Fun Center” includes a rock climbing wall, hat that I fell in love twice bungee jump trampolines and a 170 ft long, that day…first with him, then with Medora.” - A 40 ft high inflatable water slide. lady we should hire for marketing. • Pent-up demand – for many who 6 “Unexpected and moving.” – Amity Moore, experienced flooding, 2011 was the year of giving while a writer from Colorado describing the Medora the lost summer. we’re living Musical. Western North Dakota is a bustling area; Our vision is to connect people to Historic the energy industry is booming. Occasionally 8 Medora for positive, life changing experiences. we hear folks say silly things like “all the rooms calendar of It happens more than we know. Summertime are rented in Western North Dakota.” We is our best chance to make it happen; this have made provisions to have our guest rooms events newsletter is an invitation to visit Medora available for the traveling public during the this summer! We have many reasons to be summer season. -

Jiii;Lbilll11ip:Iiir

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE North Dakota COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Billings INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE i (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) JIFR 1 6 197ST COMMON: Chateau de Mores AND/OR HISTORIC: ^^^^^HS'&^^^^^ ;^^;li^ll^|:|-':^H:' :!:f ':i > ' tiP: ^:;$1: IS : ? ftl^:ll:;Pli^:li;i^l;:^llBPll|::^:":1: STREET AND NUMBER^ ;* ( ±4%- mile \ r. S/W/ of Medora. fc E. 1/2 Sec 27 T. 140N. : R. 102 W.^ CITY OR TOWN: ' CONGRES SIGNAL DISTRICT: Medora Vicinity 1 STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE North Dakota 38 Ril lings 007 Jiii;lBilll11iP:iiir < - ?•%& :x% % l^^li:l;IPi:-:l!::^|!lll^i.:l;::ll^:!:V': CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) 0 THE PUBLIC D District |2f Building QSJ Public Public Acquisition: [ | Occupied Yes: p £ Restricted D Site Q Structure [ | Private | | In Process [2J Unoccupied ] Unrestricted D Object | | Both | | Being Considered d Preservation work in progress . L] No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I I Agricultural LT] Government Q Park Q Transportation 1 1 Comments Q Commercial CD Industrial Q Private Residence G Other (Specify) d Educational d Military Q Religious I I Entertainment ]S Museum [~1 Scientific Illllwi&ii'liilsfil OWNER'S NAME: * " o > State Historical Society of North Dakota. State of North Dakota M H STREET AND NUMBER: ri- m Liberty Memorial Building d CJTY OR TOWN: STATE: ,,;' , * / QODF ?r Bismarck North Dakj0>ta>' 38 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: ' <,\7 'ttSO*-4^ M*" COUNTY: Office of Register of Deeds ' ,,r»it\ Billinks STREET AND NUMBER: j « f ' f* 1 i S ? ° Billings County Courthouse ,M I CITY OR TOWN: STATE n fvf \O »* _C O D E ' i1*1. -

Jun I 4 1994

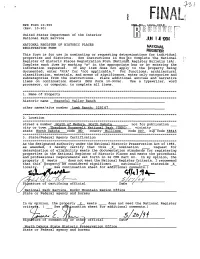

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN I 4 1994 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How Ito Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Peaceful Valley Ranch other names/site number Lamb Ranch; 32BI 67 2. Location street & number _________________________North of Medora, North Dakota _____ not for publication __ city or town Theodore Roosevelt National___________(THRO) Park vicinity __ state North Dakota code ND county Billinas code 007 zip code 58645 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

North Dakota Field Office Sundry Notice Flaring EA

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-MT-C030-2016-0212-EA June 6, 2017 Project Title: Sundry Notice Flaring Requests Location: North Dakota Field Office 99 23rd Avenue West, Suite A Dickinson, ND 58601-2619 1.0 PURPOSE AND NEED ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Purpose and Need for the Proposed Action ................................................................................. 6 1.3 The Decision to be Made .............................................................................................................. 6 1.4 Conformance with Land Use Plan(s) ............................................................................................. 7 1.5 Public Scoping and Identification of Issues ................................................................................... 7 1.6 Issues Not Analyzed ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF ALTERNATIVES ....................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Alternative A (No Action): ............................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Alternative B (Proposed -

Inside... 2 4 10 12 16

Medora Will Have A Role In Next 25 Years ince Lombardi, it is more exciting to look ahead. A few Vthe legendary thoughts about that future: Green Bay Packers Inside... football coach, z Medora must stay pristine, clean, said, “The next wholesome, and true to Harold time you make a Schafer’s promise to provide 2 touchdown, act like uncompromisingly good family sheila schafer: you’ve been there entertainment. the view from before.” Implied in z In a fast-paced, expanding North buck hill Randy Hatzenbuhler his statement was Dakota economy, more people are TRMF President that you should choosing to live here. Medora can expect to do it again play a role in helping new residents 4 and that you should not over-celebrate. to our state adopt the best of what ed schafer: April 2, 2011, quietly marked the 25th makes us North Dakotans. Medora what would anniversary of the Theodore Roosevelt can play a role in helping them harold say? Medora Foundation (TRMF). and visitors become even better We will avoid excessive celebrating, stewards. The values exhibited 10 but we will have a lot of fun in 2011. And by our workers and volunteers, the new trmf we have the expectation that Medora’s beauty of the badlands, and protected board signi cance and TRMF’s role will be land in the Theodore Roosevelt members even greater during the next twenty- ve National Park can in uence people years! It is fun to look back at 25 years to have respect and appreciation for of building and accomplishments, but North Dakota. -

Dakota D U Nord

DAKOTA DU NORD DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE Tout comme son frère jumeau du Sud avec qui il est intimement lié par l’histoire et la géographie, le Dakota du Nord est un rectangle quasi parfait, quasiment coupé en deux par le Missouri, scandé par d’immenses lacs de retenue supposés le domestiquer, ses horizons lointains s’étirant à l’infini sous des cieux immenses. Autrefois hanté par le bison pisté par les Sioux, l’état reste particulièrement rural. Sa partie orientale est tapissée d’immenses fermes exploitant les terres agricoles. L’Ouest est le royaume des Hautes Plaines ondulant à perte de vue, écorchées par les Badlands, ces « mauvaises terres » explorées par les trappeurs français des compagnies de fourrure venus à la suite de Lewis et Clark. La beauté de ses décors naturels, toujours menacés par l’exploitation du sous-sol, allait d’ailleurs inspirer à Théodore Roosevelt, fervent protecteur de l’environnement, la création du US National Forest Service, servant de modèle par la suite au US National Park Service. SOMMAIRE 04 11 UN ÉTAT D’ESPRIT ET UNE EN VILLE GUEULE D’ATMOSPHÈRE 05 13 UNE COMÉDIE COMMENT INCLURE LE MUSICALE AU CŒUR DAKOTA DU NORD DANS DES BADLANDS ! SON ITINÉRAIRE ? INSPIREZ, RESPIREZ ! 06 14 THEODORE ROOSEVELT UN REPOS BIEN NATIONAL PARK ET MÉRITÉ MEDORA LE BEST DES BADLANDS 09 15 L’ÉPOPÉE DU INFOS PRATIQUES MARQUIS DE MORÈS CONTACTS UN ÉTAT D’ESPRIT ET UNE GUEULE D’ATMOSPHÈRE L’ouverture de ses grands espaces à la colonisation amenant immigrants, chemin de fer et ranchs attisera les guerres indiennes, aboutissant à la création de plusieurs réserves. -

Tout Comme Son Frère Jumeau Du Sud Avec Qui Il Est Intimement Lié Par L

Tout comme son frère jumeau du Sud avec qui il est intimement lié par l’histoire et la géographie, le Dakota du Nord est un rectangle quasi parfait, quasiment coupé en deux par le Missouri, scandé par d’immenses lacs de retenue supposés le domestiquer, ses horizons lointains s’étirant à l’infini sous des cieux immenses. Autrefois hanté par le bison pisté par les Sioux, l’état reste particulièrement rural. Sa partie orientale est tapissée d’immenses fermes exploitant les terres agricoles. L’Ouest est le royaume des Hautes Plaines ondulant à perte de vue, écorchées par les Badlands, ces « mauvaises terres » explorées par les trappeurs français des compagnies de fourrure venus à la suite de Lewis et Clark. La beauté de ses décors naturels, toujours menacés par l’exploitation du sous-sol, allait d’ailleurs inspirer à Théodore Roosevelt, fervent protecteur de l’environnement, la création du US National Forest Service, servant de modèle par la suite au US National Park Service. Un état d’esprit et une gueule d’atmosphère L’ouverture de ses grands espaces à la colonisation amenant immigrants, chemin de fer et ranchs attisera les guerres indiennes, aboutissant à la création de plusieurs réserves. Si sa nature, souvent sauvage et altière, comme l’illustre le Theodore Roosevelt National Park, décuple les possibilités d’activités en extérieur, ce sont aussi ses vestiges hérités d’une histoire haute en couleurs, symbolisée par le destin du flamboyant Marquis de Morès, et son atmosphère provinciale décontractée, typique du Midwest, qui séduisent aujourd’hui le voyageur. Resté très authentique et préservé, bien moins fréquenté que son homonyme sudiste, riche d’un parc national, de 6 sites nationaux, de 2 National Trails, de 2 Scenic Byways, de 56 sites historiques d’état, de 18 parcs d’état, de dizaines de refuges animaliers et de plus de 150 musées dont 5 sont consacrés à la préhistoire, il permet de pénétrer dans l’intimité d’une Amérique hors des sentiers battus qui n’a que très peu changé depuis la Conquête. -

Jun I 4 1994

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN I 4 1994 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How Ito Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Peaceful Valley Ranch other names/site number Lamb Ranch; 32BI 67 2. Location street & number _________________________North of Medora, North Dakota _____ not for publication __ city or town Theodore Roosevelt National___________(THRO) Park vicinity __ state North Dakota code ND county Billinas code 007 zip code 58645 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Roosevelt, Ranches, and Resources: Theodore Roosevelt National

ROOSEVELT, RANCHES, AND RESOURCES: THEODORE ROOSEVELT NATIONAL PARK’S SEARCH FOR A BALANCE BETWEEN HUMAN AND NATURAL HISTORY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Lauren Kathleen Wiese In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Department: History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies March 2018 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title Roosevelt, Ranches, and Resources: Theodore Roosevelt National Park’s Search for a Balance Between Human and Natural History By Lauren Kathleen Wiese The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Mark Harvey Chair Thomas Isern Kristen Fellows Approved: April 10, 2018 Mark Harvey Date Department Chair ABSTRACT National parks share the same challenge debating the significance of their cultural and natural resources. In the past, many parks decided to emphasize the value of natural resources over that of their human histories. Theodore Roosevelt National Park was an exception to that trend because of its connection to President Theodore Roosevelt. In the early years of the park’s existence, National Park Service management emphasized the value of its cultural resources. The preservation and interpretation of Theodore Roosevelt’s Maltese Cross Cabin and Elkhorn Ranch were two of the park’s top priorities. Around the 1980s, park officials increasingly placed emphasis on the park’s natural resources in an attempt to balance the significance of its natural and cultural resources.