ICTD in the Popular Press: Media Discourse Around Aakash, the “World’S Cheapest Tablet”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Operations of Academic Libraries Allen Mckiel Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Faculty Research Publications (All Departments) Faculty Research 2012 Changing Operations of Academic Libraries Allen McKiel Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation McKiel, A. (2012). Changing Operations of Academic Libraries. Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference, 311-319. doi:10.5703/1288284315117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Research at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research Publications (All Departments) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Changing Operations of Academic Libraries Allen McKiel, Dean of Library Services, Western Oregon University Robert Murdoch, Assistant University Librarian for Collection Development and Technical Services, Brigham Young University Jim Dooley, Head Collection Services, University of California, Merced Abstract The article is an exploration of library operational adaptations to the changing technologies of information distribution and usage. The librarians present glimpses of the changes occurring in their library operations as they transition to services without print. The cadence of change particularly with respect to e-books continues to accelerate. The librarians summarize some of the technology changes of the last year and explore, through the evidence of their changing library operations, a range of topics including: trends in e- book “acquisition” and usage; developments in open access publishing; changes in consortia; and the role of librarians in instruction and evolving peer-review and publication processes. A Very Brief History of the Word and Alexander Luria. -

Icnl-19Q2-P1

Vol. 14 :: No. 2 :: Apr – Jun 2019 Message from the Chairman Dear IEEE Indian Members, I am happy to see that second issue of 2019 of India Council (IC) newsletter is being released. The newsletter is having information of India Council, Sections, Chapters, Affinity Groups etc., interesting articles on diverse fields of interest to our members along with few regular informative columns. I congratulate and thank the efforts taken by Mr. H.R. Mohan, Newsletter Editor. I would also like to put on record and thank the Section leaders who have extended their cooperation in providing the inputs to the newsletter. The flagship program of IEEE IC, viz. INDICON-2019, will be held in Marwadi University, Rajkot, Gujarat in collaboration with IEEE Gujarat Section during December 13-15, 2019. I hereby appeal to all IEEE members to make this INDICON another success story, as in the previous years. All India Student, Women in Engineering and Young Professional Congress (AISWYC) is to be held in Hyderabad during September 28-30, 2019. During this Second quarter of 2019, IC ExCom held on 8th June parallel to TENSYMP-2019 which was organised during June 7-9, 2019 in Kolkata. IEEE R10 Director attended the TENSYMP and interacted with IC ExCom members. Few major decisions were taken during the meeting. The changes in the IC by-laws were also approved. One of the major changes in the by-laws is to induct the advisors and various vice-chairs. A core committee consisting of current chair, chair-elect, immediate past chair, secretary and treasurer has been suggested to help the IC chair on the emerging and burning issues for consideration to the IC ExCom for approval. -

CSIC 2013( March )

50/- ` Cover Story Cover Story Building Electronic Libraries: BOOKFACE - A Facebook of Books 12 Issues and Challenges 7 ISSN 0970-647X | Volume No. 36 | Issue No. 12 | March 2013 12 | March 36 | Issue No. No. | Volume 0970-647X ISSN Technical Trend A Concept & Approach for Open Frequent Flyer Program (OFFP) 15 Article Practical Aspects of Implementing Newton-Raphson on Computers 17 Cover Story Security Corner Emergence of e-libraries Among Information Security » South-Asian Countries: Critical Software Agreements in India – Issues and Concerns 10 Points to Ponder 28 www.csi-india.org www.csi-india.org CSI Communications | March 2013 | 1 CSI Communications - Call for Articles for forthcoming issues The cover themes for forthcoming issues of CSI Communications are: • April 2013 - Big Data • May 2013 - Cryptography • June 2013 - Social Networking • July 2013 - e-Business/ e-Commerce • August 2013 - Software Project Management • September 2013 - High Performance Computing (Future topics will be announced on an ongoing basis) The Editorial Board of CSI Communications is looking for high quality technical articles for diff erent columns pertaining to the above themes or emerging and current interests. The articles should cover all aspects of computing, information and communication technologies that should be of interest to readers at large and member fraternity of CSI and around. The articles may be long (2500-3000 words) or short (1000-1500 words) authored in as the original text (plagiarism is strictly prohibited). The articles shall be peer reviewed by experts decided by the Editorial Board and the selected ones shall be published. Both theoretical and practice based articles are welcome. -

Technology in Schools

T echnology in Schools: Characteristics, t he Global Picture and a Pre and Post Use Study Stage 3: April – September 2013 Dr Barbie Clarke Siv Svanaes MSc Dr Susan Zimmermann Kathryn Crowther Contents Introduction Family Kids and Youth November 2013 0 Abstract1 This report summarises findings from an evaluation study that is looking at the feasibility and educational impact of giving one-to-one Tablets to every child in school. Research for this stage was carried out between April and September 2013 and follows Stage 1 (published December 2012), which assessed three schools that had introduced one-to-one Tablets and one control school, and Stage 2 (published July 2013), which looked at nine schools that had introduced one-to-one Tablet schemes. This report is divided into three sections. The first analyses the results from questionnaires and from the face-to-face interviews and ethnographic observation carried out in 21 schools. The second section updates the global study that was completed at Stage 1 and looks at the introduction of one-to-one Tablets in schools across the globe. The third section assesses and compares staff, pupil and parental attitudes before and after Tablets were given by Tablets for Schools to Year 7s in three schools. The first section in this stage of the research is based on an evaluation of 21 secondary schools that had chosen, or were in the process of choosing, to give pupils one-to-one Tablets, including six schools that had used one-to-one schemes since 2011, three schools that were given Tablets by Tablets for Schools for Year 7s between January and April 2013, and twelve schools that have introduced or are in the process of introducing one-to-one Tablet schemes this year. -

Starred Articles

GKCA Update st th 1 to 30 June Starred Articles 05 CII announces 10-point plan for economic revival June Economy > GDP India The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) voiced its concern over the stagnant state of the Indian economy and in a bid to rescue her, has unveiled a 10-point agenda for its revival. The remedies include fast-tracking the implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and easing of FDI (foreign direct investment) regulations in aviation and other sectors. Addressing a press conference on 5th June 2012, CII President, Adi B. Godrej, said that the primary concern for the nation was its GDP growth rate which was a mere 5.37 per cent in the last quarter was lowest in nine years. Some of the important reform to improve GDP growth as suggested by him are - early introduction of GST, the Government and the RBI inclusion of a strong monetary stimulus, correcting the current account deficit by encouraging exports and containing imports, arresting rupee slide, reducing subsidies, implementing financial sector reforms and removing bottlenecks in infrastructure growth. 06 Venus Transits between Sun and Earth June World > Space Planet Venus passed directly between the Sun and Earth on 6 June 2012, an astronomical rarity that sky watchers were eager to witness. Such a transit will not occur until 2117. The Transit of Venus, as it is called, appeared like a small dot on the Sun's elaborate circumference. This transit, which bookended a 2004-2012 pair, began at 6:09 p.m. EDT (2209 GMT) and lasted for six hours and 40 minutes. -

CSI Enewsletter H.R

Compiled & Edited by CSI eNewsletter H.R. Mohan Vol. 3 Issue 7 dt. 1st Aug 2012 AVP (Systems), The Hindu csi-enl-2012-08-01.pdf 859, Anna Salai, Chennai 600002 (combined issue for Jul & Aug 2012) [email protected] http://www.csi-india.org/web/csi/enewsletter http://infoforuse.blogspot.com/ The Open Data Center Alliance: ODCA is an independent organization that gives stakeholders a voice in shaping the future of cloud computing. It is developing a unified vision for cloud requirements – particularly focused on open, interoperable solutions for secure cloud federation, automation of cloud infrastructure, common management, and transparency of cloud service delivery. To know more about it pl. visit http://goo.gl/p0KBL 10 tips to gain control, drive innovation and lower costs with OSS: By the end of 2011, 90% of the Global 2000 will include open-source technologies as business-critical elements of their IT portfolios. It is therefore likely that your organisation is knowingly - or worse unknowingly - using free and open-source software (FOSS) in internal and customer-facing software. The challenge is creating the right balance between management controls and enabling your development teams to leverage the ever-increasing abundance of high quality, secure, free and open source code. This guide is designed to help you establish the best approach to manage the use of FOSS as part of your code strategy to drive innovation and lower costs. Access the white paper at http://goo.gl/jnkdF eBook: Personal Positioning for Engineers: In the 21st century, employment options will obviously be expanding and changing. -

Rooting the Aakash Tablet

Rooting Akaash : A short guide Ver 0.1 Sunil Thomas Thonikuzhiyil VIP Lab IIT Bombay August 18, 2013 0.1 Introduction It seems lot of guys have got the free (?) Aakash tablet recently. Here is a short guide on rooting this crap and enabling iitb wireless access on the device. If you follow this guide you will be able to install/update new software from Google play store. This procedure can possibly brick your tablet and also, I have no clue about the position of Aakash project regarding rooting. Use your discretion and you are on your own :) . 0.2 What is rooting? All the android devices are built around a tiny Linux distribution over which the Android gui runs. The underlying Linux is hidden from users and is accessible only through Android APIs. ( Of course you can install terminal application from Google play store,but you wont get root access).Most of the common an- droid applications run at a low privilege level and do not need root. The rooting procedure tries to overcome this limitation by forcibly overwriting certain files on your android tab/phone and allows you to access the device with full privi- leges. 0.3 What you need? 1) A decent Linux installation with root privilege. I did this on a Debian 7 machine. So the procedure can be replicated on any decent Linux distribution. However, your mileage may vary. 2) Rooting software. There are a variety of software for rooting android on internet. I used one named Bin4ry from xda-developers. Google it and locate it. -

Why a Cheap Tablet Is a Game-Changer

GREENLINK Why a Cheap Tablet is a Game-Changer ver the past three months that I used the commercial twin of the Aakash 2 (a pre-release unit), many people asked me where they could buy it. But this was unusual. O My mother’s maid saw the tablet last month, and asked what it cost. Under Rs 5,000, I told her. She now wants one for her grandson, to be adjusted against three months’ salary. Now, you have to see her to put this in context. She’s over 60, can’t read or write, can’t use the phone, has just about figured out the microwave and Tata Sky. But she wants a tablet for her grandson, who goes to a government school. I’m getting her an Aakash 2. Her grandson will need the GPRS-and-phone version (no WiFi at home) and that one will take a few months – sometime in 2013. So, the Aakash 2 is finally here, and this time round, it works rather well. Everything’s changed: it’s slim, smart, lighter than the iPad Mini, starts up in 22 sec, runs Android 4.0 ICS on a 1 GHz Cortex A8 processor, doubles storage to 4 GB and RAM to 512 MB. It replaces the old Aakash’s two clunky USB slots with micro-USB and micro-SD (up to 32 GB cards), throws in a budget front-facing VGA cam, and even gives two charging ports, including the micro-USB. So what’s the big deal, in a crowded tablet market? First, the price. -

Datawind Completes Aakash-2 Supply Vmware Selected for Maha

E-GOV SNAPSHOTS DataWind Completes Aakash-2 Supply 67,000 Hectares to IIT-Bombay with 12 months war- Granted for SEZs ranty and accessories . in 2013 The devices utilize multi-touch projective capacitive touch-screens manufactured at India’s only touch- screen making facility in Amritsar. The devices are powered by a Cor- tex A8-1Ghz processor, and contain 512MB of RAM. Flash memory of ataWind has completed 4GB can be supplemented by up to the supply of 100,000 32GB through its micro-SD card slot. DAakash low-cost comput- In addition to embedded Wi-Fi, ing access devices for IIT-Bombay the Aakash-2 tablet computers sup- (under the Ministry of Human port external 3G and EVDO dongles resenting a written reply in Resources Development’s National for mobile broadband data connec- the Lok Sabha, commerce Mission for Education). tivity. Supporting Google’s Android Pand industry minister The project won by DataWind 4.0 operating system, VGA camera, Anand Sharma announced the for the supply of Aakash-1 de- G-sensor, internal microphone, export numbers from the Special vices was subsequently modified speakers, and headphone jack, the Economic Zones (SEZs) during to 98,000 Aakash-2 devices and Aakash-2 is said to be a full-featured the last 3 years and the current 2,000 devices for Aakash-3, all at a tablet computer intended to break financial year. price of `2,263 (currently $41.61). the affordability barrier with the mis- In FY09-10, the value of SEZ The Aakash-2 devices are, as sion of bridging the digital divide. -

Datawind -- a Tablet for the Masses: Cases C to H

Datawind -- A Tablet for the Masses: Cases C to H 1 (C) Launch Challenges (2011/10- 2012/4) (D) Announcing Generation II (2012/04-05) (E) Back Into the Market (2012/05-06) (F) Reaction to Ubislate 7+ (2012/06-08) (G) Ubislate Upgrades & the Aakash 2 (2012/09-2013/01) (H) Gaining Scale in India, Launch in Canada (2013) 1 Updated: January 20, 2014 1 Datawind -- A Tablet for the Masses ($70-100), to include low cost Internet service. Engineers at IIT Rajasthan were working on the design of a new (C): Launch Challenges tablet that would resist falls and work in the high- humidity monsoon season. In April, two states announced that they would purchase X-O laptops from OLPC for about $230 each, rather than pursue the cheaper Aakash. The HRD, meanwhile, announced plans to invite tenders for an Aakash 2 upgrade, targeting the same price of Rs. 2,276, with the initial goal of announcing a winner for a 5 million unit contract in April 2012. In addition to Datawind, potential bidders included HCL, Bharat Heavy Electricals, and Wishtel. The HRD announced that IIT- Photo: Ubislate7.org Mumbai and the Centre for Development of Advanced Following the initial excitement, concerns about the Computing and Indian Telephone Industries public Aakash set in rapidly (Exhibits C1 and C2). Reviews service agencies would manage procurement of the new following the October 2011 launch highlighted the device, in place of IIT-Rajasthan. At the same time, the excitement and pride in developing the tablet for India. HRD reportedly was irritated that Datawind was offering Many of the same reviews, though, identified limits of the the first generation of the tablet in the open market before tablet. -

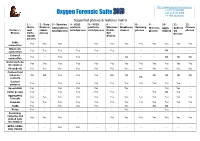

Oxygen Forensic Suite

http://www.oxygen-forensic.com +1 877 9 OXYGEN Oxygen Forensic Suite +44 20 8133 8450 +7 495 222 9278 Supported phones & features matrix 1 – 2 - Sony 3 – Symbian 4 - UIQ2 5 – UIQ3 6 - 7 - 8- 9- 10- 11- 12- Nokia Ericsson S60 platform platform platform Windows Blackberry Samsung Motorola Apple Android Chinese Feature \ and classic smartphones smartphones smartphones Mobile devices phones phones devices OS phones Phones Vertu phones 5/6 devices classic devices phones Cable Yes Yes Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes connection Bluetooth Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - - - NA - - connection Infrared Yes - Yes Yes - - NA - - NA NA NA connection General phone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes information Phonebook Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Custom field labels for NA NA Yes Yes Yes NA NA NA NA NA NA contacts NA Contact Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - pictures Speed dials Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - - Yes Yes - Caller groups Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes - - Yes NA Yes - Aggregated Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Contacts Calendar Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Tasks Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - NA NA - - Notes Yes - - - - - Yes - - Yes - - Incoming, outgoing and Yes Yes Yes - - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes missed calls information GPRS, EDGE, - - Yes Yes - - - - - - - CSD, HSCSD - and Wi-Fi traffic and sessions log Sent and received SMS, - Sent SMS - Yes Yes Yes(2) - - - - - - MMS, E-mail messages log Deleted - messages - - Yes(1) - Yes(1) - - - Yes(8) - - information Flash SMS -

Content Synchronization Applications for Aakash Tablets and Remote Educational Institutions

Content Synchronization Applications for Aakash Tablets and Remote Educational Institutions M.Tech. Stage II Report Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Technology by Debashee Tarai Roll No : 113050078 under the guidance of Prof. D. B. Phatak Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay June 2013 Abstract MHRD Sponsored project "Aakash", World's Cheapest Tablet, aims to make e- learning as the primary mode of learning in India. Tablet, being much cheaper than mobile phone with bigger screen size and lighter than laptop, is the most suitable medium to enforce E-learning in education. Aakash android tablets with Linux based operating system, are currently tested and new useful applications are developed at IIT Bombay. This entire project contains two individual applications, Local Synchro- nization and Remote Synchronization Application. Remote Content Synchronization application aims at distributing contents in a net- work efficient manner to remote Institutions distributed at different geographical loca- tions. It makes use of RSYNC tool for content transfer and RSA public private key pair to make the application more secured and fast. This report describes the architecture, implementation details and analyze the performance of the remote synchronization application. Several tests have been conducted and analysis of the obtained results shows that performance of the Remote Synchronization application is nearly three times better then conventional scp based transfer and RSA key pair reduce the total transfer time to a great extent. Local Content Synchronization application has been developed for Aakash tablets inorder to synchronize contents between students and teachers, providing the users an interface to submit files, download files and view the details of all submissions and sharing at real time.