Lecture 6. Fundamentals of Atmospheric Chemistry: Part 1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photophoretic Spectroscopy in Atmospheric Chemistry – High-Sensitivity Measurements of Light Absorption by a Single Particle

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 3191–3203, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-3191-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Photophoretic spectroscopy in atmospheric chemistry – high-sensitivity measurements of light absorption by a single particle Nir Bluvshtein, Ulrich K. Krieger, and Thomas Peter Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zurich, 8092, Switzerland Correspondence: Nir Bluvshtein ([email protected]) Received: 28 February 2020 – Discussion started: 4 March 2020 Revised: 30 April 2020 – Accepted: 16 May 2020 – Published: 18 June 2020 Abstract. Light-absorbing organic atmospheric particles, the UV–vis wavelength range, attributing them with a nega- termed brown carbon, undergo chemical and photochemi- tive (cooling) radiative effect. However, light-absorbing or- cal aging processes during their lifetime in the atmosphere. ganic aerosol, termed brown carbon (BrC), with wavelength- The role these particles play in the global radiative balance dependent light absorption (λ−2 − λ−6) in the UV–vis wave- and in the climate system is still uncertain. To better quan- length range (Chen and Bond, 2010; Hoffer et al., 2004; tify their radiative forcing due to aerosol–radiation interac- Kaskaoutis et al., 2007; Kirchstetter et al., 2004; Lack et al., tions, we need to improve process-level understanding of ag- 2012b; Moosmuller et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2007), may be the ing processes, which lead to either “browning” or “bleach- dominant light absorber downwind of urban and industrial- ing” of organic aerosols. Currently available laboratory tech- ized areas and in biomass burning plumes (Feng et al., 2013). -

Transition State Theory. I

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 5.62 Physical Chemistry II Spring 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. 5.62 Spring 2007 Lecture #33 Page 1 Transition State Theory. I. Transition State Theory = Activated Complex Theory = Absolute Rate Theory ‡ k H2 + F "! [H2F] !!" HF + H Assume equilibrium between reactants H2 + F and the transition state. [H F]‡ K‡ = 2 [H2 ][F] Treat the transition state as a molecule with structure that decays unimolecularly with rate constant k. d[HF] ‡ ‡ = k[H2F] = kK [H2 ][F] dt k has units of sec–1 (unimolecular decay). The motion along the reaction coordinate looks ‡ like an antisymmetric vibration of H2F , one-half cycle of this vibration. Therefore k can be approximated by the frequency of the antisymmetric vibration ν[sec–1] k ≈ ν ≡ frequency of antisymmetric vibration (bond formation and cleavage looks like antisymmetric vibration) d[HF] = νK‡ [H2] [F] dt ! ‡* $ d[HF] (q / N) 'E‡ /kT [ ] = ν # *H F &e [H2 ] F dt "#(q 2 N)(q / N)%& ! ‡ $ ‡ ‡* ‡ (q / N) ' q *' q *' g * ‡ K‡ = # trans &) rot ,) vib ,) 0 ,e-E kT H2 qH2 ) q*H2 , gH2 gF "# (qtrans N) %&( rot +( vib +( 0 0 + ‡ Reaction coordinate is antisymmetric vibrational mode of H2F . This vibration is fully excited (high T limit) because it leads to the cleavage of the H–H bond and the formation of the H–F bond. For a fully excited vibration hν kT The vibrational partition function for the antisymmetric mode is revised 4/24/08 3:50 PM 5.62 Spring 2007 Lecture #33 Page 2 1 kT q*asym = ' since e–hν/kT ≈ 1 – hν/kT vib 1! e!h" kT h! Note that this is an incredibly important simplification. -

Eyring Equation

Search Buy/Sell Used Reactors Glass microreactors Hydrogenation Reactor Buy Or Sell Used Reactors Here. Save Time Microreactors made of glass and lab High performance reactor technology Safe And Money Through IPPE! systems for chemical synthesis scale-up. Worldwide supply www.IPPE.com www.mikroglas.com www.biazzi.com Reactors & Calorimeters Induction Heating Reacting Flow Simulation Steam Calculator For Process R&D Laboratories Check Out Induction Heating Software & Mechanisms for Excel steam table add-in for water Automated & Manual Solutions From A Trusted Source. Chemical, Combustion & Materials and steam properties www.helgroup.com myewoss.biz Processes www.chemgoodies.com www.reactiondesign.com Eyring Equation Peter Keusch, University of Regensburg German version "If the Lord Almighty had consulted me before embarking upon the Creation, I should have recommended something simpler." Alphonso X, the Wise of Spain (1223-1284) "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler." Albert Einstein Both the Arrhenius and the Eyring equation describe the temperature dependence of reaction rate. Strictly speaking, the Arrhenius equation can be applied only to the kinetics of gas reactions. The Eyring equation is also used in the study of solution reactions and mixed phase reactions - all places where the simple collision model is not very helpful. The Arrhenius equation is founded on the empirical observation that rates of reactions increase with temperature. The Eyring equation is a theoretical construct, based on transition state model. The bimolecular reaction is considered by 'transition state theory'. According to the transition state model, the reactants are getting over into an unsteady intermediate state on the reaction pathway. -

Atmospheric Chemistry

Atmospheric Chemistry John Lee Grenfell Technische Universität Berlin Atmospheres and Habitability (Earthlike) Atmospheres: -support complex life (respiration) -stabilise temperature -maintain liquid water -we can measure their spectra hence life-signs Modern Atmospheric Composition CO2 Modern Atmospheric Composition O2 CO2 N2 CO2 N2 CO2 Modern Atmospheric Composition O2 CO2 N2 CO2 N2 P 93bar 1bar 6mb 1.5bar surface CO2 Tsurface 735K 288K 220K 94K Early Earth Atmospheric Compositions Magma Hadean Archaean Proterozoic Snowball CO2 Early Earth Atmospheric Compositions Magma Hadean Archaean Proterozoic Snowball Silicate CO2 CO2 N2 N2 Steam H2ON2 O2 O2 CO2 Additional terrestrial-type atmospheres Jurassic Earth Early Mars Early Venus Jungleworld Desertworld Waterworld Superearth Modern Atmospheric Composition Today we will talk about these CO2 Reading List Yuk Yung (Caltech) and William DeMore “Photochemistry of Planetary Atmospheres” Richard P. Wayne (Oxford) “Chemistry of Atmospheres” T. Gredel and Paul Crutzen (Mainz) “Chemie der Atmosphäre” Processes influencing Photochemistry Photons Protection Delivery Escape Clouds Photochemistry Surface OCEAN Biology Volcanism Some fundamentals… ALKALI METALS The Periodic Table NOBLE GASES One outer electron Increasing atomic number 8 outer electrons: reactive Rows called PERIODS unreactive GROUPS: similar Halogens chemical C, Si etc. have 4 outer electrons properties SO CAN FORM STABLE CHAINS Chemical Structure and Reactivity s and p orbitals d orbitals The Aufbau Method works OK for the first 18 elements -

Chapter 1 – Introduction

1 Chapter 1 – Introduction 1.1 – Scientific Background Knowledge of gas phase compounds and their chemical reactions are pivotal to our understanding of chemistry. The conditions these molecules are in can vary dramatically, from temperatures as low as 10 K in the depths of the interstellar medium, to more than 1000 K in the combustion of hydrocarbons in engines. The chemistry in these systems is dominated by highly reactive, unstable compounds, leading to fast and complex chemistry occurring. In order to accurately understand these systems, we must be able to observe these unstable species and measure the kinetics of their formation and destruction. While molecular spectra and reaction rate constants of these reactive compounds can be computed with theoretical calculations, they must be benchmarked with experimental measurements to determine their accuracy. To that end, one major focus in experimental gas phase chemistry is to better understand these unstable molecules and their reactions in systems such as atmospheric chemistry and astrochemistry. 1.1a – Atmospheric Chemistry Understanding Earth’s atmosphere and the chemistry behind it has been a major topic in gas phase chemistry since the mid-20th century, when the impact of fossil fuel usage and air pollution resulting from the Industrial Revolution became apparent. The dominant molecule in Earth’s atmosphere is N2 (77% of the atmosphere) followed by O2 (21%) and argon (1%). The remaining components are largely stable molecules, such as CO2 and H2O. 2 Figure 1.1: The average temperature (left) and pressure (right) profiles of the Earth’s lower atmosphere, consisting of the troposphere and stratosphere. -

Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry

THE PERIODIC TABLE OF THE ELEMENTS OF GREEN AND SUSTAINABLE CHEMISTRY Paul T. Anastas Julie B. Zimmerman The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Copyright © 2019 by Paul T. Anastas and Julie B. Zimmerman All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information and contact; address www.website.com Published by Press Zero, Madison, Connecticut USA 06443 Cover Design by Paul T. Anastas ISBN: 978-1-7345463-0-9 First Edition: January 2020 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry To Kennedy and Aquinnah 3 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the entirety of the international green chemistry community for their efforts in creating a sustainable tomorrow. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Evan Beach for his thoughtful and constructive contributions during the editing of this volume, Ms. Kimberly Chapman for her work on the graphics for the table. In addition, the authors would like to thank the Royal Society of Chemistry for their continued support for the field of green chemistry. 4 The Periodic Table of the Elements of Green and Sustainable Chemistry Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Answers to Selected Problems

Answers to Selected Problems Chapter 1 1.2. 0.55 A 1.3. +-y-.z- ++ y+, z+ t-t-y+,~+ -!-!y+.z+ *x+ lx+ t-x+ *s -ls i- s- 1- s+ -l s+ t- s+ BeO triplet CO singlet NO doublet 1.5. "Ionic bonds" using 6p electrons are stronger than those using 6s electrons (Pb2+2Br- p Pb4 +4Br-). "Covalent bonds" with 6s electrons are stronger than those with 6p electrons (PbMe4 > PbMe2)' The energy gap between 6p and 6s orbitals is larger than that for 2p and 2s orbitals. 1.6. SOl = Cda + b + c + d + e + f) S02 = C2(a + b - c - d + e +f) S03 = C3(a - b + c - d + e + f) 541 542 Answers to Selected Problems S04 = C4 (a + b + c + d - e +f) SOs = Cs(a + b - c - d - e +f) SOb = C6 (a - b - c + d - e + f) 1.9. B. c. D d. 0 1.10. There is no vibrational distortion of a homonuclear diatomic that can lower its symmetry. Chapter 2 2.2. Charge density qi = 1; n-bond order Pii = I. 2.3. Il.E = 1l.E,. + IlE,; 1l.E, = 2(1 - i 12) {J. 2.4. Second-order perturbations are not additive. In double union of even AHs, the second order terms are large and cannot be ignored. Chapter 3 3.1. 4 J -jill jm Answers to Selected Problems 543 3.2. a. Ii) I1E n = 2-=( 2 + --3) {J = 0.92{J " ,,/17.7 j17.7 I1Enp = 2 ( --~- + 1 ) {J = 1.28{J j17.7 )17.7 (ii) I1En, = 2 ( -~= + ~-- ) {J = 0.84{J )20.7 fti0 (iii) I1Enp = 2( -- 6- + -~){J = 1.47{J ,,/17.7 v17.7 (iv) I1En, = 2 ( -/ + 2 ) {J = 1.35{J ..;20.7 )20.7 Thus (iii) > (ii) > Ii): (iv) > (ii). -

Bimolecular Reaction Rate Coefficients in the Last Lecture, We Learned Qualitatively the Reaction Mechanisms of Hydrocarbon Combustion

Combustion Chemistry Hai Wang Stanford University 2015 Princeton-CEFRC Summer School On Combustion Course Length: 3 hrs June 22 – 26, 2015 Copyright ©2015 by Hai Wang This material is not to be sold, reproduced or distributed without prior written permission of the owner, Hai Wang. Lecture 4 4. Bimolecular Reaction Rate Coefficients In the last lecture, we learned qualitatively the reaction mechanisms of hydrocarbon combustion. To make this description quantitative, we will need to have a basic knowledge of reaction rate theories. While the rate coefficients of a large number of combustion reactions are experimentally measured, reaction rate theories are often necessary to interpret the experimental data. We shall focus our discussion here to bimolecular reactions of the type A + B → C + D and leave the discussion for unimolecular reactions to a later time. 4.1 Hard Sphere Collision We discussed earlier that an elementary chemical reaction requires molecular collision. The rate coefficient of a bimolecular reaction is essentially the product of reaction probability of two reactants (A and B) upon collision at a given temperature γ(T) and the frequency of collision ZAB, k(T) [A][B] = γ(T) ZAB (4.1) Here we assume that molecules may be described by rigid spheres. Figure 4.1 shows several scenarios of molecular encounter. Starting from the head-on collision, an offset of the two axes of molecular motion leads to off-center collision. Suppose the diameter of A and B are σA and σB, respectively. The limiting off-center collision would have a spacing equal to (σA+σB)/2 between the two axes of molecular motions. -

ECG Environmental Briefs ECGEB No

ECG Environmental Briefs ECGEB No. 3 Atmospheric chemistry at night Atmospheric chemistry is driven, in large part, by sunlight. Air pollution, for example, and especially the formation of ground-level ozone, is a day-time phenomenon. So what happens between the hours of sunset and sunrise? This Brief examines the night-time chemistry of the HO2 + NO OH + NO2 [R3] troposphere (the lower-most atmospheric layer from the 3 NO2 + light (λ < 420nm) NO + O( P) [R4] surface up to 12 km). Atmospheric chemistry is 3 predominantly oxidation chemistry, and the vast majority of O( P) + O2 O3 [R5] gases from emission sources are oxidised within the Night-time tropospheric chemistry troposphere. The unique aspects of atmospheric oxidation chemistry at night are best appreciated by first reviewing the It is an obvious statement: there is no sunlight at night. day-time chemistry. Therefore the night-time concentration of OH is (almost) zero. Instead, another oxidant, the nitrate radical, NO , is Day-time tropospheric chemistry 3 generated at night by the reaction of NO2 with ozone. NO3 The first Environmental Brief (1) considered in detail the radicals further react with NO2 to establish a chemical photolysis of ozone at near-ultraviolet wavelengths to equilibrium with N2O5. generate electronically excited oxygen atoms: NO2 + O3 NO3 + O2 [R6] 1 O3 + light (λ < 340nm) O( D) + O2 [R1] NO3 + NO2 ⇌ N2O5 [R7] Reaction R1 is a key process in tropospheric chemistry Reaction R6 happens during the day too. However, NO3 is 1 because the O( D) atom has sufficient excitation energy to quickly photolysed by daylight, and therefore NO3 and its react with water vapour to produce hydroxyl radicals: equilibrium partner N2O5 are both heavily suppressed during 1 the day. -

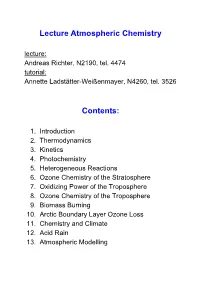

Lecture Atmospheric Chemistry Lecture: Andreas Richter, N2190, Tel

Lecture Atmospheric Chemistry lecture: Andreas Richter, N2190, tel. 4474 tutorial: Annette Ladstätter-Weißenmayer, N4260, tel. 3526 Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Thermodynamics 3. Kinetics 4. Photochemistry 5. Heterogeneous Reactions 6. Ozone Chemistry of the Stratosphere 7. Oxidizing Power of the Troposphere 8. Ozone Chemistry of the Troposphere 9. Biomass Burning 10. Arctic Boundary Layer Ozone Loss 11. Chemistry and Climate 12. Acid Rain 13. Atmospheric Modelling Atmospheric Chemistry - 2 - Andreas Richter Literature for the lecture Guy P. Brassuer, John J. Orlando, Geoffrey S. Tyndall (Eds): Atmospheric Chemistry and Global Change, Oxford University Press, 1999 Richard P. Wayne, Chemistry of Atmospheres, Oxford University Press, 1991 Colin Baird, Environmental Chemistry, Freeman and Company, New York, 1995 Guy Brasseur and Susan Solom, Aeronomy of the Middle Atmosphere, D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1986 P.W.Atkins, Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 1990 Note Many of the images and other information used in this lecture are taken from text books and articles and may be subject to copyright. Please do not copy! Atmospheric Chemistry - 3 - Andreas Richter Why should we care about Atmospheric Chemistry? population is growing emissions are growing changes are accelerating Atmospheric Chemistry - 4 - Andreas Richter Why should we care about Atmospheric Chemistry? scientific interest atmosphere is created / needed by life on earth humans breath air humans change the atmosphere by o air pollution o changes in land use o tropospheric oxidants o acid rain o climate changes o ozone depletion o ... atmospheric chemistry has an impact on atmospheric dynamics, meteorology, climate The aim is 1. to understand the past and current atmospheric constitution 2. -

Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry

Lecture 1: Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry Required Reading: FP Chapter 1 & 2 Additional Reading: SP Chapter 1 & 2 Atmospheric Chemistry CHEM-5151 / ATOC-5151 Spring 2005 Prof. Jose-Luis Jimenez Outline of Lecture 1 • Importance of atmospheric chemistry • Atmospheric composition: big picture, units • Atmospheric structure – Pressure profile – Temperature profile – Spatial and temporal scales • Air Pollution: – historical origin: AP deaths – Overview of problems: smog, acid rain, stratospheric O3, climate change, indoor pollution • Continue in Lecture 2 1 Importance of Atmospheric Chemistry • Atmosphere is very thin and fragile! – Earth diameter = 12,740 km – Earth mass ~ 6 * 1024 kg – Atmospheric mass ~ 5.1 * 1018 kg – 99% of atmospheric mass below ~ 50 km – Solve in class: order of magnitude of mass of the oceans? Mass of entire human population? • Main driving forces to study Atm. Chem. are big practical problems: – Deaths from air pollution, smog, acid rain, stratospheric ozone depletion, climate change Structure of Course • Introduction •“Tools” – Atmospheric transport (BT) – Kinetics (ED) & Photochemistry – Aerosols (QZ) – Cloud and Fog chemistry • “Problems” – Smog chemistry – Acid rain chemistry – Aerosol effects – Stratospheric Ozone – Climate change 2 Interdisciplinarity of Atm. Chem. • Very broad field of both fundamental and applied nature: – Reaction modeling → chemical reaction dynamics and kinetics – Photochemistry → atomic and molecular physics, quantum mechanics – Aerosols → surface chemistry, material science, colloids -

Turekian Reflections

RETROSPECTIVE RETROSPECTIVE Turekian reflections Mark H. Thiemensa,1, Andrew M. Davisb,c, Lawrence Grossmanb,c, and Albert S. Colmanb aDepartment of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; and bDepartment of the Geophysical Sciences and cEnrico Fermi Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637 Karl Karekin Turekian (1927–2013) was a Columbia’s Lamont Geological Observatory man of remarkable scientificbreadth,with had only been established a few years before. innumerable important contributions to ma- ItwasduringtheseyearsthatKarlbegan rine geochemistry, atmospheric chemistry, to acquire the skills that led to his rapid cosmochemistry, and global geochemical emergence as a leader in geochemistry. His cycles. He was mentor to a long list of stu- interactions with Paul Gast and his advisor Karl Karekin Turekian. dents, postdoctorate scholars, and faculty Larry Kulp were particularly influential, as it (at Yale and elsewhere), a leader in geo- was then that he began his quest to attack the chemistry, a prolific author and editor, and largest geochemical problems by application probability event,” as each of the required had a profound influence in shaping his of intellect and new measurement capabilities. features was in and of itself of low probability. department at Yale University. Karl was a Karl began by assaulting the element Not unlike the very low, but finite probability true scholar and interested in everything, strontium, measuring its concentration in in quantum mechanical tunneling, Karl met scientific and nonscientific. As his Yale everything he could get his hands on (rocks, Roxanne at a New Year’sEvepartyandthey colleague George Veronis reflected, “Karl sediments, corals, ocean waters, and so forth) were married some three months later.