Country Report for Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSI: Trends and Changes, 1974–80

SSI: Trends and Changes, 1974-80 byLennaKennedy* By the end of 1980, the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program was making monthly cash assistance payments, aver- aging $170, to almost 4.2 million aged, blind, and disabled per- sons. When SSI payments began in January 1974, the number of recipients was 3.2 million and the average payment was $117. Since 1975, both SSI payments and Social Security bene- fits have been automatically adjusted each year to correspond with increases in the Consumer Price Index. A number of other trends in addition to growth can be discerned in the size of the population served, as well as in their categorical, geographic, and age distributions. This article discusses some of these trends and changes, using program data for the end of each cal- endar year through 1980. It also presents a brief summary of the program at the end of that period. The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program differed from State to State. In addition, payments provides cash assistance to residents of the 50 States, the within a State varied depending on criteria such as District of Columbia, and the Northern Mariana Islands special living arrangements-for instance, a recipient who are categorically eligible-aged 65 and older, blind, sharing an apartment or living in a domiciliary care fa- or disabled-and whose income and resources are with- cility. A few States also made higher supplementary in the limitations imposed by law and regulations. The payments to persons residing in metropolitan areas. maximum Federal SSI payment, originally $140 * per Although SSI has been affected by a number of legis- month for an individual without countable income and lative changes, the program has experienced little net ex- $210 for a couple, had risen by mid-1980 to $238 for an pansion since its beginning. -

TO the GENERAL ASSEMBLY REGARDING MEMBERSHIP in the UNITED NATIONS L~R(Jduflory NOTE

Chapter VII PRACTICE RELATIVE TO RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY REGARDING MEMBERSHIP IN THE UNITED NATIONS l~R(JDUflORY NOTE .............................................................. 109 PART 1. TABLE OF APPLICATIONS AND OF ACTIONS TAKEN THEREON BY THE SECU- RITY COUNCIL AND THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, 1975-1980 Note .............................................................................. 109 A. Applications recommended by the Security Council ................................ 109 B. Applications that failed to obtain a recommendation ............................... 109 C. Discussion of the question in the Security Council, 197s.1980 ...................... 109 D. Applications pendin on I January 1975 ........................................... II0 E. Applications submitted between I January 1975 and 31 December 1980 .............. I IO F. Votes in the Security Council on draft resolutions and amendments concerning applicattons for admission to membership in the United Nations. 1975-1980 ....................... II0 G. Votes in the General Assembly on draft resolutions concerning Security Council recommen- dations for admission to membership in the United Nations, 1975-1980 ................ III PART II. CONSIDERATION OF THE ADOPTION OR AMENDMENT OF RULES J8d0OF THE PROVISIONAL RULES OF PROCEDURE Note ............................................................................... II2 PART Ill. PRESENTATION OF APPLICATIONS Note.. ............................................................................. II2 PART IV. REFERENCE -

17 December 1980, the 4

(c) To request the Secretary-General to submit at Noting the letter dated 15 December 1980 from the the end of this period a report on the developments in Permanent Representative of Lebanon to the the situation and the measures taken to implement Secretary-General, ss resolution 338 (1973). Convinced that the present situation has serious Adopted at the 2256th meeting 2 consequences for peace and security in the Middle by /4 votes to none.' East, Reaffirming its call for the strict respect for the territorial integrity, unity, sovereignty and political in dependence of Lebanon within its internationally rec Decisions ognized boundaries, At the same meeting, following the adoption of res I. Takes note of the report of the Secretary olution 481 (1980), the President made the following General on the United Nations Interim Force in Leba statement on behalf of the members of the Council: non; "In connexion with the adoption of the resolution 2. Decides to renew the mandate of the Force for a on the renewal of the mandate of the United Nations period of six months, that is, until 19 June 1981, and Disengagement Observer Force, I have been au reiterates its commitment to the full implementation of thorized to make the following complementary the mandate of the Force throughout its entire area of statement on behalf of the Security Council regard operation up to the internationally recognized bound ing the resolution just adopted: aries, according to the terms of reference and .. · As is known, the report of the Secretary guidelines as stated and confirmed in the appropriate General on the United Nations Disengagement Ob Security Council resolutions; server Force51 states, in paragraph 27, that, "De 3. -

Maps Cited by Congress When Designating Wilderness

Maps Summary Table In 2003 long-time NPS Wilderness Coordinator Wes Henry prepared this table that was intended for inclusion in the updated Reference Manual 41 – Wilderness Management. Wes died soon thereafter. PEER has updated the table to reflect information through 2014. RM 41: Section F: DRAFT January 21, 2003 Maps Cited by Congress when Designating Wilderness. The table lists in: Column 2: maps cited by Congress when designating NPS wilderness (in chronological order by date of enactment); Column 3: date of an official legal description prepared after designation, and Column 4: whether a post-enactment official boundary map was prepared. NPS AREA – CONGRESSIONAL DATE OF DATE OF WILDERNESS MAP NUMBER OFFICIAL OFFICAL MAP DATE AND DATE, CITED LEGAL IN LAW DESCRIPTION Craters of the 131-91,000 December 1970 NPS cited Moon – Oct. 1970 March 1970 legislative map Petrified Forest - NP-PF-3320-O December 1970 NPS cited October 1970 November 1967 legislative map Lava Beds – NM-LB-3227H December 1972 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Lassen Volcanic – NP-LV-9013C June 1973 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Point Reyes – 612-90,000-B May 1978 February 1977 October 1976 September 1976 Bandelier – 315-20,014-B August 1978 August 1978 October 1976 May 1976 Black Canyon of 144-20,017 January 1977 January 1977 the Gunnison – May 1973 October 1976 Chiricahua - 145-20,007-A May 1978 January 1977 October 1976 September 1973 Great Sand Dunes 140-20,006-C December 1976; January 1980 October 1976 February 1976 Revised: -

NSIAD-91-166 El Salvador: Military Assistance Has Helped Counter But

ll~liftvl St.at,ths (;thnt*ral At~t~ollrll,irrb~~fi~e ___ “.-- -.__II..,“-1- __..I ._ ..” _^“_l_ __“”..__ _,. ._. .._... ,”.. *“, 11- -_-_._.... __-. --.-----l_-..-.--- -_--_---- Report, t,o the I-IorWY~able GAO Kd ward M. Kcmr~ody, IJ .S. Stmde .l__l-l” _-_1 “--m-“1.. April I!)91 EL SALVADOR Military Assistance Has Helped Counter but Not Overcome the Insurgency -.-“_(- _.~ ._-. _.- _-.l___l_^-__l_-__ - -... -“----p--m- -.-.-- --- National Security and International Affairs Division B-242216 April 23,199l The Honorable Edward M. Kennedy United States Senate Dear Senator Kennedy: In responseto your request, this report describeswhat impact U.S. military assistanceto El Salvador has had on that country’s ability to counter insurgent forces, how the assistance has changed that country’s military capabilities, and how the assistancehas attempted to instill and support respect for democracy and human rights. Unless you release its contents earlier, we plan no further distribution of this report until 30 days from its issue date. At that time, we will send copies of the report to appropriate congressional committees and the Secretariesof Defenseand State. Major contributors to this report are listed in appendix I. If you have any questions, please call me on (202) 2754128. Sincerely yours, Joseph E. Kelley Director, Security and International Relations Issues l3xecutive Swnmary Since 1980, the United States has provided over $1 billion in military aid Purpose to El Salvador to assist the government in its fight against an insur- gency. Senator Edward M. Kennedy requested that GAO review the U.S. -

DECEMBER 1980 THIRD ANNUAL WINTER WONDERS WORKSHOP Escape the Midwinter Blahs by Attending the Winter Workshops at Gateway En• Vironmental Study Center

Environmental Education Advisory councit A voluntary organization in support of Environmental Education for New York DECEMBER 1980 THIRD ANNUAL WINTER WONDERS WORKSHOP Escape the midwinter blahs by attending the winter workshops at Gateway En• vironmental Study Center. These workshops will provide dozens of classroom activities & will enable you to ~articipate in special activities at Gateway National Recreation Area--including the 'Gateway to Flight' celebration to be held at Floyd Bennett Field in May. SATURDAY, JANUARY 31 - 9:30 A.M.-3 P.M.-Rain shine or snow; in the event of a blizzard, you will be notified about alternate date. Admission: There will be no admission charge if you are an EEAC member. For additional info.: Mrs. Ruth Eilenberg, Coordinator Gateway - Phone: 252-7307 WORKSHOP CHOICES: AIR CRAFTS: FLIGHT IN THE CLASSROOM - Eilene Evan.6, P.S. 127, Vi~t«ct 20. Hand.6-on wo~k.6hop u.6ing kite.6 6 othe~ ea.6ily con• .6t~ucted ai~c~a6t to illu.6t~a.te the p~inc.-ipa.l.6 06 6light. You will come away with ided4, a.cilvitie.6 6 le.6~on plan.6. WHICH WAY IS THE WIND BLOWING? - Ma~vin Itzkowitz, head 06 the Ma..thema.t-<.c.6 Un-<.t. 1 h.(..6 .(..6 a .6e..6.6ion on compa.6.6 ~eacU.ng. It will .6how how mapping S compa.6.6 ~ea.ding can be u.6ed to .6t~ength• en math .6kill.6 & concept.6. FIELD WALK: FLIGHT & OTHER ADAPTATIONS - John W. Komin.6ki, Science A.6.6ociate, Bd. -

45 FR 36901 (May 30, 1980)

FEDERAL REGISTER: 45 FR 36901 (May 30, 1980) DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AGENCY: Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSM) 30 CFR 716.17, 717.17, 816.42, 816.46, 817.42, and 817.46 DOI-OSM Discharge from Mine Areas: Revision of Standards for Effluent Limits and Sedimentation Ponds Legal Authority Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, 30 U.S.C. Sec. 1201 et seq. SUMMARY: REASON FOR INCLUDING THIS ENTRY The Department of the Interior (DOI) considers these rules to be of general public interest because they concern the environment and the public health and safety, and because they will help to improve the quality of the waters of the United States. STATEMENT OF PROBLEM On December 13, 1977, the Office of Surface Mining (OSM) published initial regulations for control of sediment in discharges from areas of surface coal mining and reclamation activities, and on March 13, 1979, published final regulations. The rules established specific limitations -- called "effluent limitations" -- on the total suspended solids (TSS) iron and manganese content of the discharges from the mining area. The rules also required that all runoff be passed through sedimentation ponds and established minimum design criteria for these ponds. Essentially, sedimentation ponds improve the quality of discharges by detaining runoff until heavier particles settle to the bottom of the pond. The TSS limitations were essentially the same as those established by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on April 26, 1977, (42 FR 21380), and on January 12, 1979, (44 FR 2586). EPA's regulations were promulgated pursuant to the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. -

United Nations Commission on the Truth for El Salvador Issued Its Report Documenting the Human Rights Tragedy of the 1980-1991 Period

August 10, 1993 Vol. V, Issue No. 7 EL SALVADOR ACCOUNTABILITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS: THE REPORT OF THE UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ON THE TRUTH FOR EL SALVADOR INDEX Introduction ..............................................................................2 The Origins of the Truth Commission ............................... 4 Purging the Military: The Ad Hoc Commission .............. 7 The Truth Commission Begins Operations ..................... 10 Pressures on the Commission............................................ 11 The Content of the Report .................................................. 14 Cases Ascribed to Government Forces ....................... 15 Cases Ascribed to the FMLN ....................................... 17 Recommendations of the Commission ...................... 19 Reaction to the Report in El Salvador............................... 20 The Amnesty......................................................................... 23 An Evaluation of the Truth Commission Report ........... 24 FMLN Cases.................................................................... 25 News From Americas Watch - page 2 - Vol. V, Issue No. 7 Amnesty and Prosecutions........................................... 27 The US Role........................................................................... 29 "It would be good to keep in mind that, above all, what must be determined is the identity of those fundamentally responsible for these captures...those who gave the order, those who permitted them, even those who reveled C as in a Roman circus -

Price Changes in 1980: Double-Digit Inflation Persists Consumer Prices Jumped 12.4 Percent and Producer Prices, 11

Price changes in 1980: double-digit inflation persists Consumer prices jumped 12.4 percent and producer prices, 11. 7 percent; costs for energy items rose, but mortgage interest rates fluctuated wildly and a severe drought raised food prices CRAIG HOWELL, DAVE CALLAHAN, AND OTHERS For the second consecutive year, the rate of inflation in 12.8-percent advance in 1979 .' The slowdown in 1980 both retail and primary markets registered double-digit was partly due to the deceleration in the rate of increase increases. The Consumer Price Index for All Urban for the finished energy goods index, which climbed 27.7 Consumers (CPI-U) moved up 12.4 percent, following a percent, after soaring 58 .0 percent in 1979 . Finished 13.3-percent advance during 1979. Prices for all major consumer food prices rose 7.3 percent in 1980, virtually consumer expenditure categories, except apparel and en- the same as during the previous 12 months . Prices for tertainment, increased at least 10 percent over the year. finished goods other than food and energy rose more in Mortgage interest costs advanced 27.6 percent, com- 1980 (11 .0 percent) than in 1979 (9 .3 percent); on aver- pared with a 34.7-percent climb in the preceding year. age these prices advanced rapidly in early 1980 and Prices paid by consumers for energy items were up 18.1 then moderated as the year progressed. At the earlier percent. Although this was larger than the increases re- stages of processing, the price index for intermediate corded for most other cpl components, it was half as goods moved up 12.5 percent over the year, after in- large as the 1979 surge of 37.4 percent. -

Financial Regulation (16 December 1980)

Financial Regulation (16 December 1980) Caption: Financial Regulation of 16 December 1980 amending the Financial Regulation of 21 December 1977 as regards the use of the ecu in the general budget of the European Communities. Source: Official Journal of the European Communities (OJEC). 20.12.1980, n° L 345. [s.l.]. ISSN 0378-6978. Copyright: All rights of reproduction, public communication, adaptation, distribution or dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. The documents available on this Web site are the exclusive property of their authors or right holders. Requests for authorisation are to be addressed to the authors or right holders concerned. Further information may be obtained by referring to the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/financial_regulation_16_december_1980-en-94a90811-80b3-4ae6-995b- 7c383ac532b1.html Publication date: 05/09/2012 1 / 3 05/09/2012 Financial Regulation of 16 December 1980 amending the Financial Regulation of 21 December 1977 as regards the use of the ECU in the general budget of the European Communities (80/1176/EEC, Euratom, ECSC) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, and in particular Article 78 (h) thereof, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, and in particular Article 209 thereof, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community, -

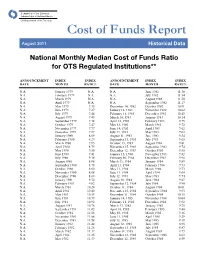

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A. -

Download Subject Index to Current Population Reports: December 1980

CURRENT POPULATION Subject REPORTS Special Studies Index to Series P-23 No. 109 CURRENT U.S. Department of Commerce POPULATION BUREAU OF THE CENSUS REPORTS: December 1980 THE LIBRAE OF. THE rev CURRENT P OPULATION REPORTS Special S tudies Series P-23 No. 109 Subject I ndéx to CURRENT POPULATION REPORTS: December 1 980 Issued S eptember 1981 A s º, vºy - * res of U.S. D epartment of Commerce Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary Joseph B. Wright, Jr., Deputy Secretary Robert G. Dederick, Assistant Secretary for Economic Affairs BUREAUF O THE CENSUS Daniel B. Levine, Acting Director BUREAUF O THE CENSUS Daniel B. Levine, Acting Director Meyer Zitter, Acting Associate Director for Demographic Fields POPULATION D IVISION Roger A. Herriot, Chief fLibrary o Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Indexo t Current population reports. (Current p opulation reports. Series P-23, Special studies; no. 109) Supt. o f Docs. n.: C 3.186:P-23/109 1. C urrent population reports—Indexes. 2. United States—Population—Statistics— Indexes. I. United States. Bureau of the Census. II. Title: Current population reports. III. Series, HA2O3.A218 no. 109 312'.0973s 81-607089 (312'.0973] A ACR2 For s ale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. Postage stamps not acceptable; currency submitted at sender's risk. Remittances from foreign countries must be by international money order or by a draft on a U.S. bank. Current Population Reports are sold in two subscription packages: Series P-20, P-23, P-27, and P-60 are available for $70 per year ($17.50 additional for foreign mailing); Series P-25, P-26, and P-28 are available for $90 per year ($22.50 additional for foreign mailing).