Pari-Mutuels: What Do They Mean and What Is at Stake in the 21St Century? Bennett Liebman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aqueduct Racetrack Is “The Big Race Place”

Table of Contents Chapter 1: Welcome to The New York Racing Association ......................................................3 Chapter 2: My NYRA by Richard Migliore ................................................................................6 Chapter 3: At Belmont Park, Nothing Matters but the Horse and the Test at Hand .............7 Chapter 4: The Belmont Stakes: Heartbeat of Racing, Heartbeat of New York ......................9 Chapter 5: Against the Odds, Saratoga Gets a Race Course for the Ages ............................11 Chapter 6: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Bill Hartack - 1964 ....................................................13 Chapter 7: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Taylor Rice - Today ...................................................14 Chapter 8: In The Travers Stakes, There is No “Typical” .........................................................15 Chapter 9: Our Culture: What Makes Us Special ....................................................................18 Chapter 10: Aqueduct Racetrack is “The Big Race Place” .........................................................20 Chapter 11: NYRA Goes to the Movies .......................................................................................22 Chapter 12: Building a Bright Future ..........................................................................................24 Contributors ................................................................................................................26 Chapter 1 Welcome to The New York Racing Association On a -

Dan Patch Awards Order — 2Ft

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2020 ©2020 HORSEMAN PUBLISHING CO., LEXINGTON, KY USA • FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION CALL (859) 276-4026 Watch Dan Patch Awards Dinner, Red Carpet Live! The name of the 2019 Horse of the Year will be announced Sunday night, Feb. 23, at the annual U.S. Harness Writers Association’s (USHWA) Dan Patch Awards dinner at Rosen Shingle Creek in Orlando, Fla. But even if you aren’t among the attendees you will be able to watch the announcement live via USHWA’s Facebook page. After a one-hour cocktail party, the awards ceremony will get underway at 6:30 p.m., and will be available via the Facebook page. At approximately 9:30 p.m., emcees Roger Huston and Jason Settlemoir will announce the winner of the E. Roland Harriman Horse of the Year trophy, which fol- lows the revealing of the names of the Pacer of the Year and Trotter of the Year. To access USHWA’s Facebook page, please click here. The entire video will also be available on the U.S. Trotting Asso- ciation’s YouTube page the following day, Monday, Feb. 24, by clicking here. Post time for the evening is 5:30 p.m., with a one-hour Red Carpet cocktail reception sponsored by Shartin N. Also star- ring on the Red Carpet will be Heather Vitale and Heather Wilder, with the two Heathers broadcasting live on their in- dividual Facebook pages. It’s your guarantee to see who’s wearing what and what the attendees have to say about the festivities. Continues on page 2 ›››› — DAN PATCH AWARDS ORDER — 2FT . -

Hedging Your Bets: Is Fantasy Sports Betting Insurance Really ‘Insurance’?

HEDGING YOUR BETS: IS FANTASY SPORTS BETTING INSURANCE REALLY ‘INSURANCE’? Haley A. Hinton* I. INTRODUCTION Sports betting is an animal of both the past and the future: it goes through the ebbs and flows of federal and state regulations and provides both positive and negative repercussions to society. While opponents note the adverse effects of sports betting on the integrity of professional and collegiate sporting events and gambling habits, proponents point to massive public interest, the benefits to state economies, and the embracement among many professional sports leagues. Fantasy sports gaming has engaged people from all walks of life and created its own culture and industry by allowing participants to manage their own fictional professional teams from home. Sports betting insurance—particularly fantasy sports insurance which protects participants in the event of a fantasy athlete’s injury—has prompted a new question in insurance law: is fantasy sports insurance really “insurance?” This question is especially prevalent in Connecticut—a state that has contemplated legalizing sports betting and recognizes the carve out for legalized fantasy sports games. Because fantasy sports insurance—such as the coverage underwritten by Fantasy Player Protect and Rotosurance—satisfy the elements of insurance, fantasy sports insurance must be regulated accordingly. In addition, the Connecticut legislature must take an active role in considering what it means for fantasy participants to “hedge their bets:” carefully balancing public policy with potential economic benefits. * B.A. Political Science and Law, Science, and Technology in the Accelerated Program in Law, University of Connecticut (CT) (2019). J.D. Candidate, May 2021, University of Connecticut School of Law; Editor-in-Chief, Volume 27, Connecticut Insurance Law Journal. -

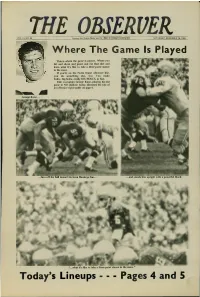

Where the Game Is Played Today's Lineups

VOL. ill, NO. THE49____________________________________ ServingOBSERVER the Notre Dame and St. Mary’s College Community________________________ Saturday, November 16. 1968 Where The Game Is Played This is where the game is played. Where you hit and shove and grunt and eat that dirt and learn what it’s like to take a three-point stance in the snow. If you’re on the Notre Dame offensive line, you do something else, too. You make holes...big holes , really BIG HOLES, in fact. Irish co-captain George Kunz, playing his last game in ND stadium today, discusses the role of an offensive right tackle on page 6. George Kunz.... ....fires off the ball toward his Iowa Hawkeye foe.... ... and stands him upright with a powerful block. “...what it’s like to take a three-point stance in the snow.” Today’s Lineups - - - Pages 4 and 5 PAGE 2 THE OBSERVER SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 1968 The Starters IRISH OFFENSE LT Mike McCoy (77) C Billy Kidd (55) SE Jim Seymour (85) RT Eric Norri (72) RG Todd Woodhull (88) Sports Parade LT Jim Reilly (61) RE Chick Lauck (93) RT Terry Story (72) LG Ed Tuck (69) LB Tim Kelly (42) TE Joel Stevenson (89) C Mike Oriard (54) LB Jim Wright (40) QB Ken Bonifay (17) By Milt Richman, UPI columnist RG Tom McKinley (79) LB Bob Olson (36) FB Kenny Bounds (49) RT George Kunz (78) LB Larry Schumacher(24) TB Steve Harkey (41) TE Jim Winegardner (96) LH John Gasser (46) EL John Sias (21) Jacques Returns QB Joe’Theismann (7) RH Chuck Zloch (27) TECH DEFENSE FB Ron Dushney (38) S Don Reid (11) LE Steve Foster (91) Today's Sports Parade is written by James F. -

U.S. Lotto Markets

U.S. Lotto Markets By Victor A. Matheson and Kent Grote January 2008 COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FACULTY RESEARCH SERIES, PAPER NO. 08-02* Department of Economics College of the Holy Cross Box 45A Worcester, Massachusetts 01610 (508) 793-3362 (phone) (508) 793-3710 (fax) http://www.holycross.edu/departments/economics/website *All papers in the Holy Cross Working Paper Series should be considered draft versions subject to future revision. Comments and suggestions are welcome. U.S. Lotto Markets Victor A. Matheson† and Kent Grote†† August 2008 Abstract Lotteries as sources of public funding are of particular interest because they combine elements of both public finance and gambling in an often controversial mix. Proponents of lotteries point to the popularity of such games and justify their use because of the voluntary nature of participation rather than the reliance on compulsory taxation. Whether lotteries are efficient or not can have the usual concerns related to public finance and providing support for public spending, but there are also concerns about the efficiency of the market for the lottery products as well, especially if the voluntary participants are not behaving rationally. These concerns can be addressed through an examination of the U.S. experience with lotteries as sources of government revenues. State lotteries in the U.S. are compared to those in Europe to provide context on the use of such funding and the diversity of options available to public officials. While the efficiency of lotteries in raising funds for public programs can be addressed in a number of ways, one method is to consider whether the funds that are raised are supplementing other sources of funding or substituting for them. -

Download Full Book

Vegas at Odds Kraft, James P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kraft, James P. Vegas at Odds: Labor Conflict in a Leisure Economy, 1960–1985. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3451. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3451 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 14:41 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Vegas at Odds studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library Vegas at Odds Labor Confl ict in a Leisure Economy, 1960– 1985 JAMES P. KRAFT The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kraft, James P. Vegas at odds : labor confl ict in a leisure economy, 1960– 1985 / James P. Kraft. p. cm.—(Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9357- 5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9357- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Labor movement— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 2. Labor— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 3. Las Vegas (Nev.)— Economic conditions— 20th century. I. Title. HD8085.L373K73 2009 331.7'6179509793135—dc22 2009007043 A cata log record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Those Restless Little Boats on the Uneasiness of Japanese Power-Boat Gamblers

Course No. 3507/3508 Contemporary Japanese Culture and Society Lecture No. 15 Gambling ギャンブル・賭博 GAMBLING … a national obession. Gambling fascinates, because it is a dramatized model of life. As people make their way through life, they have to make countless decisions, big and small, life-changing and trivial. In gambling, those decisions are reduced to a single type – an attempt to predict the outcome of an event. Real-life decisions often have no clear outcome; few that can clearly be called right or wrong, many that fall in the grey zone where the outcome is unclear, unimportant, or unknown. Gambling decisions have a clear outcome in success or failure: it is a black and white world where the grey of everyday life is left behind. As a simplified and dramatized model of life, gambling fascinates the social scientist as well as the gambler himself. Can the decisions made by the gambler offer us a short-cut to understanding the character of the individual, and perhaps even the collective? Gambling by its nature generates concrete, quantitative data. Do people reveal their inner character through their gambling behavior, or are they different people when gambling? In this paper I will consider these issues in relation to gambling on powerboat races (kyōtei) in Japan. Part 1: Institutional framework Gambling is supposed to be illegal in Japan, under article 23 of the Penal Code, which prescribes up to three years with hard labor for any “habitual gambler,” and three months to five years with hard labor for anyone running a gambling establishment. Gambling is unambiguously defined as both immoral and illegal. -

Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government

Papers on the Local Governance System and its Implementation in Selected Fields in Japan No.16 Japanese Publicly Managed Gaming (Sports Gambling) and Local Government Yoshinori ISHIKAWA Executive director, JKA Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) Except where permitted by the Copyright Law for “personal use” or “quotation” purposes, no part of this booklet may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission. Any quotation from this booklet requires indication of the source. Contact Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) (The International Information Division) Sogo Hanzomon Building 1-7 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 Japan TEL: 03-5213-1724 FAX: 03-5213-1742 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.clair.or.jp/ Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance (COSLOG) National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677 Japan TEL: 03-6439-6333 FAX: 03-6439-6010 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www3.grips.ac.jp/~coslog/ Foreword The Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) and the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) have been working since FY 2005 on a “Project on the overseas dissemination of information on the local governance system of Japan and its operation”. On the basis of the recognition that the dissemination to overseas countries of information on the Japanese local governance system and its operation was insufficient, the objective of this project was defined as the pursuit of comparative studies on local governance by means of compiling in foreign languages materials on the Japanese local governance system and its implementation as well as by accumulating literature and reference materials on local governance in Japan and foreign countries. -

PUBLIC CONSULTATION on PROPOSED AMENDMENTS to LAWS GOVERNING GAMBLING ACTIVITIES 1. the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) Is Seekin

PUBLIC CONSULTATION ON PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO LAWS GOVERNING GAMBLING ACTIVITIES 1. The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) is seeking feedback on proposed amendments to laws governing gambling. Background 2. Singapore adopts a strict but practical approach in its regulation of gambling. It is not practical, nor desirable in fact, to disallow all forms of gambling, as this will drive it underground, and cause more law and order issues. Instead, we license or exempt some gambling activities, with strict safeguards put in place. Our laws governing gambling seek to maintain law and order, and minimise social harm caused by problem gambling. 3. Our approach has delivered good outcomes. First, gambling-related crimes remain low. Casino crimes have contributed to less than 1% of overall crime since the Integrated Resorts started operations in 2010. The number of people arrested for illegal gambling activities has remained stable from 2011 to 2020. Second, problem gambling remains under control. Based on the National Council on Problem Gambling's Gambling Participation Surveys that are conducted every three years, problem and pathological gambling rates have remained relatively stable, at around 1%. 4. To continue to enjoy these good outcomes, we need to make sure that our laws and regulations can address two trends in the gambling landscape. First, advancements in technology. The internet and mobile computing have made gambling products more accessible. People can now gamble anywhere and anytime through portable devices such as smart phones. Online gambling has been on the uptrend. Worldwide revenue from online gambling is projected to almost triple, from US$49 billion in 2018 to US$135 billion in 2027.1 Second, the boundaries between gambling and gaming have blurred. -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring. -

A Friend Or Foe in the New Era of Sports and Gaming Competition?

Wednesday, December 5, 2018 Sports Betting: A Friend or Foe in the New Era of Sports and Gaming Competition? Moderator: Scott Finley: CEO and Managing Director of Scott Finley International Racing Speakers: Scott J. Daruty: Executive Vice President Content & Media, The Stronach Group Bill Knauf: Vice President Business Operations, Monmouth Park Racetrack Dean McKenzie: Director, New Zealand Thoroughbred Racing Inc Sam Swanell: CEO, PointsBet Ms. Wendy Davis: Good. Let's continue on this theme. Let everybody get their coffee and come on back in. Basically, the second section, second session of our sports wagering panels this morning, "Friend or Foe in the New Era of Sports and Gaming Competition". First of all, I'd like to thank our session sponsor, which is Daily Racing Form and the Stronach Group for our beverage break. Leading the discussion for this panel is Scott Finley. He's CEO and managing director of Scott Finley International Racing. His background is in business development, marketing, technology deployment in the horse racing and betting industries. He's owned and managed his own international racing and betting consulting practice since 2002. This certainly makes him uniquely qualified to lead this discussion. I know they've spent a lot of time getting all these comments put together in a logical format here. I just mentioned to Dean he had requested that we have his PowerPoints available for you. If you would like to take them, I will have — there will be copies of those PowerPoints in the back of the room if you'd like to get those on your way out. -

2010 Pioneer Football

C.W. POST PIONEERS C.W.2011 FOOTBALLPOST LONG ISLAND UNIVERSITY Juma McKenley Xavier Brown Xavier Brown Darnel Williams Erik Anderwkavich 22010010 2011PIONEERPI Women’sONE SoccerER Media FFOOTBALLO GuideOTBALL 1 1 C.W. POST PIONEERS TTHISHIS IISS 2011 FOOTBALL CC.W..W. PPOSTOST AATHLETICSTHLETICS 22009-10009-10 QQUICKUICK FFACTS:ACTS: Overall Record: 208-101-4 (.668 winning pct.) Conference Record: 123-46 (.727 winning pct.) • 18 student-athletes were named All-Americans. • 71 student-athletes received All-Conference recognition. • Five programs won their conference championships (men’s cross country, men’s soccer, men’s lacrosse, base ball, women’s lacrosse). • Six programs participated in NCAA Championships. • Men’s Lacrosse repeated as NCAA Champions, capturing its second straight title and third overall in program history. WOMEN’S SPORTS Basketball Cross Country Field Hockey Lacrosse Soccer Softball Swimming Tennis Volleyball MEN’S SPORTS Baseball Basketball Cross Country Football Lacrosse Soccer C.W. POST ATHLETICS MISSION STATEMENT Intercollegiate athletics is a key component to the success of Long Island University. The Intercollegiate Athletics Program at C.W. Post de- velops leadership skills, personal character, discipline and competitiveness in an environment where the foremost goal is academic achieve ment and the successful completion of the University’s academic requirements for graduation. Each student-athlete is a representative of the University and C.W. Post, and will conform to the letter and spirit of all rules and