To Go to Sonny Rollins Interview On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ronnie Scott's Jazz C

GIVE SOMEONE THE GIFT OF JAZZ THIS CHRISTMAS b u l C 6 z 1 0 z 2 a r J e MEMBERSHIP TO b s ’ m t t e c o e c D / S r e e i GO TO: WWW.RONNIESCOTTS.CO.UK b n m e OR CALL: 020 74390747 n v o Europe’s Premier Jazz Club in the heart of Soho, London ‘Hugh Masekela Returns...‘ o N R Cover artist: Hugh Masekela Page 36 Page 01 Artists at a Glance Tues 1st - Thurs 3rd: Steve Cropper Band N Fri 4th: Randy Brecker & Balaio play Randy In Brasil o v Sat 5th: Terence Blanchard E-Collective e Sun 6th Lunch Jazz: Atila - ‘King For A Day’ m b Sun 6th: Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Orchestra e Mon 7th - Sat 12th: Kurt Elling Quintet “The Beautiful Day” r Thurs 10th: Late Late Show Special: Brandee Younger: A Tribute To Alice Coltrane & Dorothy Ashby Sun 13th Lunch Jazz: Salena Jones & The Geoff Eales Quartet Sun 13th: Dean Brown - Rolajafufu The Home Secretary Amber Rudd came up with Mon 14th - Tues 15th : Bettye LaVette Wed 16th - Thurs 17th : Marcus Strickland Twi-Life a wheeze the other day that all companies should Fri 18th - Sat 19th : Charlie Hunter: An Evening With publish how many overseas workers they employ. Sun 20th Lunch Jazz: Charlie Parker On Dial: Presented By Alex Webb I, in my naivety, assumed this was to show how Sun 20th: Oz Noy Mon 21st: Ronnie Scott’s Blues Explosion much we relied upon them in the UK and that a UT Tues 22nd - Wed 23rd: Hugh Masekela SOLD O dumb-ass ban or regulated immigration system An additional side effect of Brexit is that we now Thurs 24th - Sat 26th: Alice Russell would be highly harmful to the economy as a have a low strength pound against the dollar, Sun 27th Lunch Jazz: Pete Horsfall Quartet whole. -

Bbc Music Jazz 4

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10th NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11th NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12th NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13th NOVEMBER MONDAY 14th NOVEMBER JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - SOMERSET BLUES: 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES 00.00 - 00.00 - WITH JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) THE STORY OF ACKER BILK Clarke Peters tells the strory of Acker Bilk, Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Al Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some of his one of Britain’s finest jazz clarinettists. Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. favourite directors. NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE JAZZ JUNCTIONS: JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - 01.00 - OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley's tribute to his hero Dudley Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall in Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo Moore, with material from Jazz FM's 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. archive. GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - 02.00 - GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POND: 02.00 - TRUMPET MASTERS (PT. 2) JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. 1) JAZZ ON FILM (PT. -

This Is Our Music V.2-2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BCU Open Access 20/11/2015 16:38:00 This Is Our Music?: Tradition, community and musical identity in contemporary British jazz Mike Fletcher As we reach the middle of the second decade of the twenty-first century we are also drawing close to the centenary of jazz as a distinct genre of music. Of course, attempting to pinpoint an exact date would be a futile endeavour but nevertheless, what is clear is that jazz has evolved at a remarkable rate during its relatively short lifespan. This evolution, which encompassed many stylistic changes and innovations, was aided in no small part by the rapid technological advances of the twentieth century. Thus, what was initially a relatively localised music has been transformed into a truly global art form. Within a few short decades of the birth of the music, records, radio broadcasts and globe-trotting American jazz performers had already spread the music to a listening audience worldwide, and it was not long after this that musicians began to make attempts to ‘adapt jazz to the social circumstances and musical standards with which they were more familiar’.1 In the intervening decades, subsequent generations of indigenous musicians have formed national lineages that run parallel to those in America, and variations in cultural and social conditions have resulted in a diverse range of performance practices, all of which today fall under the broad heading of jazz. As a result, contemporary musicians and scholars alike are faced with increasing considerations of ownership and authenticity, ultimately being compelled to question whether the term jazz is still applicable to forms of music making that have grown so far away from their historical and geographic origins. -

40 X 40 a Celebration of Print Ronnie Scott's 1959-69: Photography by Freddy Warren

EXHIBITIONS (admission free) Please see page 3 for Christmas & Barbican Library Foyer exhibition: 3 - 31 December 2019 New Year 40 x 40 A Celebration of Print Opening Times Greenwich Printmakers was founded in 1979 with the primary aim of providing a permanent display of members’ work in their own gallery. It is run as a co-operative, staffed and administered by the artists. As well as showing across the UK, they have shown in Germany, Canada, the USA and Moscow. Greenwich Printmakers have also shown in many prestigious exhibitions in the UK, the most notable being at the National Theatre and the Barbican. In their fortieth anniversary year they have shown at the Salvation Army International HQ and Watts Gallery Artists Village near Guildford in Surrey. Their artists are regularly selected for the RE Masters and the National Original Print Exhibition at Bankside Gallery, the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and The Discerning Eye. Barbican Music Library exhibition: 12 October 2019 - 4 January 2020 Ronnie Scott's 1959-69: Photography by Freddy Warren A warm and intimate series of portraits marking the 60th anniversary of London’s legendary jazz club and the publication of a new book. To celebrate the work of Freddy Warren, a selection of photographs is showcased in this exhibition that captures the atmosphere and movement of jazz. His photographs include performance shots and off–stage pictures of Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Duke Ellington, Nina Simone and more. A previously unseen archive of his work also features behind the scene images of Ronnie Scott, personally overseeing the construction of the club's iconic Soho venue. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 19451970

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Society and Culture Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 19451970 Williams, KA http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/4429 10.1558/jazz.v7i1.113 Jazz Research Journal Equinox Publishing All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. [JRJ 7.1 (2013) 113-131] (print) ISSN 1753-8637 doi:10.1558/jazz.v7i1.113 (online) ISSN 1753-8645 Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 1945–1970 Katherine Williams Department of Music, Plymouth University [email protected] Abstract This article explores the ways in which jazz was presented and mediated through venue in post-World War II London. During this period, jazz was presented in a variety of ways in different venues, on four of which I focus: New Orleans-style jazz commonly performed for the same audiences in Rhythm Clubs and in concert halls (as shown by George Webb’s Dixielanders at the Red Barn public house and the King’s Hall); clubs hosting different styles of jazz on different nights of the week that brought in different audiences (such as the 100 Club on Oxford Street); clubs with a fixed stylistic ideology that changed venue, taking a regular fan base and musicians to different locations (such as Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club); and jazz in theatres (such as the Little Theatre Club and Mike West- brook’s compositions for performance in the Mermaid Theatre). -

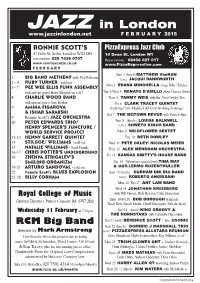

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Ebook / John Mclaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra

RCRGU0FGTS \\ John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra: Score Edition, Score (Paperback) » eBook Joh n McLaugh lin and th e Mah avish nu Orch estra: Score Edition, Score (Paperback) By Professor of Land Studies John McLaughlin Alfred Music, 2007. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra was the most influential band of the 1970s fusion jazz movement. Fresh from turning the jazz world upside down on Miles Davis immortal In a Silent Way, John McLaughlin teamed with Jan Hammer, Rick Laird, Billy Cobham, and Jerry Goodman to form the Mahavishnu Orchestra, an amazing fusion of jazz, blues, rock and Indian music. This book contains John s own miniature scores to 28 classic Mahavishnu songs. Titles: A Lotus on Irish Streams * Awakening * Be Happy * Birds of Fire * Celestial Terrestrial * Commuters * Dawn * Dream * Earth Ship * Eternity s Breath * Faith * Hope * If I Could See * Lila s Dance * Meeting of the Spirits * Miles Beyond * Noonward Race * On the Way Home to Earth * One Word * Open Country Joy * Opus I * Pastoral * Resolution * Sanctuary * Sapphire Bullets of Pure Love * The Dance of Maya * Thousand Island Park * Vital Transformation * You Know, You Know. READ ONLINE [ 1.53 MB ] Reviews It is an amazing ebook i actually have at any time study. We have read and so i am certain that i will likely to read through yet again once again later on. Your way of life period will likely be change when you complete looking at this pdf. -- Cristina Rowe Extremely helpful to all class of individuals. It really is writter in straightforward terms instead of diicult to understand. -

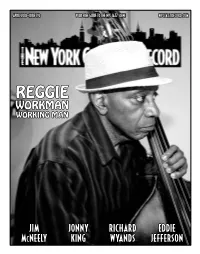

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

ISSUE 22 ° May 2011

Ne w s L E T T e R Editor: Dave Gelly ISSUE 22 ° May 2011 Ready for the Second Round We have now success- packs on the theme ‘The fully completed the devel- Story of British Jazz’, empha- opment phase of the sising the people and places Simon Spillett Talkin’ (and Access Development involved, and also the wider Playin’) Tubby Project for the Heritage social and cultural aspect of A celebration of the Music, Life Lottery Fund bid. Working the times. Some of these are NATIONAL JAZZ ARCHIVE JAZZ NATIONAL and times of the late, great British with Essex Record Office touched on in the Archive’s and Flow Associates, our exhibition at the Barbican jazz legend Tubby Hayes education and outreach Music Library (see below). With John Critchinson (piano), consultants, we have Alec Dankworth (bass) and developed our plans to Clark Tracey (drums) apply for the second NJA Exhibition Saturday 23 July 2011 round – funding of £388,000 opens at Barbican 1.30 - 4.30pm, at Loughton Methodist Church for a three-year delivery Music Library project. Tickets £10 from David Nathan at The Archive’s exhibition the Archive (cheques payable to This will involve building at the Barbican Music Library National Jazz Archive) on what we have so far is set to open on Tuesday 3rd See also Pages 5 & 6 achieved in increasing access May. It presents the people, to our collections during the places, bands and great jazz development phase - con- events, portrayed in rare serving, cataloguing, digitis- photos, posters, books, ing, developing outreach magazines and ephemera facilities, and collaborating from our fast-growing on projects with those who collection. -

Professor Doctor FRIEDRICH GULDA Called to the Waiter, Member to Qualify for the Final Eliminations

DOWN BEAT, august 1966 VIENNESE COOKING written by Willis Conover Professor Doctor FRIEDRICH GULDA called to the waiter, member to qualify for the final eliminations. Then he'd have to "Dry martini!'' The waiter, thinking he said "Drei martini|'' go through it all again. brought three drinks. It's the only time Gulda's wishes have The jurors were altoist Cannonball Adderley, trombonist J. J. ever been unclear or unsatisfied. Johnson, fluegelhornist Art Farmer, pianist Joe Zawinul, The whole city of Vienna, Austria snapped to attention when drummer Mel Lewis and bassist Ron Carter. The jury Gulda, the local Leonard Bernstein decided to run an chairman who wouldn't vote except in a tie, was critic Roman international competition for modern jazz. Waschko. The jury's refreshments were mineral water, king- For patrons he got the Minister of Foreign Affair, the Minister size cokes, and Viennese coffee. For three days that was all of Education, the Lord Mayor of Vienna and the they drank from 9:30 am till early evening. The jury took la Amtsfuhrender fur Kultur, Volksbildung und Schulverwaltung duties seriously. der Bundeshauptstadt Wien. For his committee of honor he A dialog across the screen might go like this. enlisted the diplomatic representatives of 20 countries, the Young lady in the organization (escorting contestant): "Mr. directors of 28 music organizations, and Duke Ellington. For Watschko?" expenses he obtained an estimated $80,000. For contestants Watschko: "Yes?" he got close to 100 young jazz musicians from 19 countries- Young lady: "Candidate No. 14 " some as distant as Uruguay and Brazil. -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz.