FORTY YEARS of REINDEER HERDING in Me MACKENZIE DELTA, N.W.T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region of the Northwest Territories in Canada, to Study the Factors Which

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 031 332 RC 003 530 By-Ervin, A. M. New Northern Townsmen in Inuvik. Canadian Dept. of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa (Ontario). Report No- MDRP -5 Pub Date May 68 Note-30p. Available from-Chief, Northern Science Research Group, Department ofIndianAffairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, Canada EDRS Price MF -$0.25 HC 41.60 Descmptors-*Acculturation, Adult Education, Alcoholism, *American Indians, *Culture Conflict, *Educational Disadvantagement, Employment Qualifications, *Eskimos, Folk Culture, Housing Deficiencies, Relocation, Social Status, Status Need, Summer Programs, Values Identifiers-Canada, Metis A study was conducted in Inuvik, a planned settlement in the Mackenzie Delta region of the Northwest Territories in Canada, to study the factors which work against adaptation among the Indians, Eskimos, and Metis to the "urban milieu" of Inuvik. Field techniques included informal observation and intensive intemews with selected native and white informers. Factors examined were the educational, lob-skill, and housing needs which affect the*natives; thcir bush culture which includes sharing and consumption ethics and a derogatory attitude toward status seeking; and heavy drinking, a predominant problem among the natives. Some recommendations were; (1) an adult education program stressing the value systems of town life should be established; (2) the Trappers Association should be revived to provide equipment arid encouragement to natives more suited to trapping than town life; and (3) a summer's work program should be instituted for teenage native males. A related document is RC 003 532. (RH) New Northern Townsmen in Inuvik \ By A. M. Ervin 4s/ il? 14. ar, >et MDRP 5 .jUL40(4* 4.0. -

Canada. Northern Administration Branch Records 1940-1973

Canada. Northern Administration Branch Records 1940-1973 AN INVENTORY G-1979-003 Prepared by Janice Brum and Lorna Dosso Northwest Territories Archives Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre Government of the Northwest Territories Yellowknife, N.W.T. April 1993 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Administrative History 3 Custodial History 4 Scope and Contents 5 File list 11 100 – Administration 11 200 - Arctic and Eskimo Affairs 19 300 - Engineering Projects 62 400 - Game and Forest Protection 85 500 - Territorial Secretariat 106 600 – Education 188 1000 – General 260 20 - Individual Name Files 269 ---- - [Cooperative Development] 270 Index 272 Appendix A (Original file classification list) 1 Introduction Canada. Northern Administration Branch [text]. - 1949-1973 This accession consists of 34 meters of material, primarily textual created from 1949 to 1973. The records were created by the Northern Administration Branch and its various predecessors as a result of the federal governments activities in administering the Northwest Territories. A small number of photographs were located in the files during processing, however these images have been left in their original files and no attempt has been made to catalogue them. Although temporary file lists had been created in the past, final arrangement and description was completed in 1993. This project was financed in part via the Canadian Council of Archives Backlog Reduction Program. The Project Archivists were Janice Brum and Lorna Dosso, supervised by the Senior Archivist, Ian Moir. During this processing, the collection was reduced from approximately 145 meters to its present 34 meters. The bulk of the records were purely administrative and were culled from the collection. -

Your Big River Journey – Credit Information

Your Big River Journey – Credit Information Fort Smith Header image, aerial photo of Fort Smith; photograph by GNWT. Fort Smith Hudson's Bay Company Ox Carts, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N-1979-058: 0013 Portage with 50 ft scow, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N-1979-058: 0015 Fifty-foot scow shooting a rapid, CREDIT: NWT Archives/C. W. Mathers fonds/N- 1979-058: 0019 Henry Beaver smudging with grandson, Fort Smith; photograph by Tessa Macintosh. Symone Berube pays the water, Fort Smith, video by Michelle Swallow. Mary Shaefer shows respect to the land, Fort Smith, video by ENR. Paddle stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Grand Detour Header image, Grand Detour; photograph by Michelle Swallow. Image of Grand Detour portage, CREDIT: NWT Archives/John (Jack) Russell fonds/N-1979-073: 0100 Image of dogs hauling load up a steep bank near Grand Detour, CREDIT: NWT Archives/John (Jack) Russell fonds/N-1979-073: 0709 Métis sash design proposal; drawing by Lisa Hudson. Lisa Hudson wearing Métis sash; photograph by Lisa Hudson. Métis sash stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Slave River Delta Header image, Slave River Delta, Negal Channel image; photograph by GNWT. How I Respect the Land: Conversations from the South Slave, Rocky Lafferty, Fort Resolution; video by GNWT ENR. Male and female scaup image; photograph by Danica Hogan. Male and female mallards image; photograph by JF Dufour. Slave River Delta bird image; photograph by Gord Beaulieu. Snow geese stamp; illustration by Sadetło Scott. Fort Resolution Header image, aerial photo of Fort Resolution; photograph by GNWT. -

OCTOBER 2017-Final.Pmd

Inuvialuit Regional Corporation October 2017 Ata ... uvva ... from the IRC Board! IRC It was a hot and dry summer here in the ISR! Many were ♦ As part of the Canada 150 celebrations, the Race pleased with their harvest of whales, fish and berries! the Peel canoe race took place June 28 to 30. Fall is definitely in the air with the changing of colours Seventeen teams began paddling from Fort and even some snow. Hope you enjoy reading the IRC McPherson to Aklavik, stopping at the old Knute Board Summary which is mailed to beneficiaries Lang camp for a mandatory rest, before being following every IRC Board meeting. greeted at the finish line. IRC Board Meetings ♦ The North American Indigenous Games in The most recent board meeting was August 22, 23 and Toronto July 16 to 22 celebrated sports and 24 with the next scheduled for November 21, 22, 23 culture. The Ulukhaktok Western Drummers and and 24. Additional meetings will be held by Dancers represented NWT proudly; performing teleconference as required. for the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, Elizabeth Dowdeswell, the closing ceremonies and various Around the ISR venues. ♦ Communities celebrated the 33rd Anniversary of the signing of the IFA with feasts and barbecues. ♦ It was a busy August and September with the IRC, IDC and Inuvik CC co-hosted a lunch arrival of cruise ships in the ISR communities of featuring country foods along with cultural Ulukhaktok, Paulatuk and Tuktoyaktuk, from the entertainment at the Inuvialuit Corporate Centre. Crystal Serenity (1000+ passengers) to Canada C3’s Polar Prince (60 passengers). -

The New Aklavik: Search for the Site Merrill, C

NRC Publications Archive Archives des publications du CNRC The new Aklavik: search for the site Merrill, C. L.; Pihlainen, J. A.; Legget, R. F. This publication could be one of several versions: author’s original, accepted manuscript or the publisher’s version. / La version de cette publication peut être l’une des suivantes : la version prépublication de l’auteur, la version acceptée du manuscrit ou la version de l’éditeur. Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur: Engineering Journal, 43, 1, pp. 52-57, 1960-02-01 NRC Publications Record / Notice d'Archives des publications de CNRC: https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=4c857b6c-bbe3-42fa-ba2e-3ab4a87884f5 https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=4c857b6c-bbe3-42fa-ba2e-3ab4a87884f5 Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB. Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at [email protected]. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information. Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. -

Araneae, Salticidae) in the Westernhemisphere

ARCTIC VOL. 35, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 1982) P. 426-428 Extreme Northern and Southern Distribution Records for Jumping Spiders (Araneae, Salticidae) in the WesternHemisphere BRUCE CUTLER' ABSTRACT. In Alaska and Canada the northern limit of salticid spider distribution corresponds closely to the boreal forest-tundra ecotone. The only occurrence in the polar tundrais at Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada. In South America, Puerto Deseado, Argentine marks the southernmost record. Key words: Salticidae, jumping spider, distribution RGSUM6. En Alaska comme au Canada, la limite nordique de la distribution de la saltique correspond de prescelle de I'Ccotone de la for& borCale et de la toundra. On ne la trouvedans la toundra polaire qu'hTuktoyaktuk, dans les Territoires duNord-Ouest, au Canada. En AmCrique du Sud, Puerto Deseado, en Argentine, marque la limite australe. Mots clts: Salticidts, araignte sauteuse, distribution Traduit pour le journal par Maurice Guibord. comparing the detailed labeldata with the specimens, and INTRODUCTION the map in Ferris (1974), I determined that the specimens The Salticidae are the largest spider family, comprising were all collectedat the ecotone, or in the forest-tundra, over 3000 species, mostly tropical, but with good repre- but not inthe polar tundra proper. Only at Tuktoyaktuk, in sentation in temperate areas. The number of species the northwest of the Northwest Territories, Canada, do decreases rapidly as one approaches polar regions. For salticids exist on the polar tundra. This area was not example, Chickering(1946) notes approximately 230 spe- glaciated duringthe last glacial period, and the specimens cies from Panama, while Richman and Cutler (1977) list may represent a possible relict population(National Atlas 290 species from allof North America northof Mexico (an of Canada, 1974; Ritchie, 1977). -

Environment Canada

MACKENZIE DELTA AND BEAUFORT COAST SPRING BREAKUP NEWSLETTER Report 2017-010 May 25, 2017 at 19:00 UTC Friends of Steven Solomon (Dustin Whalen, Paul Fraser, Don Forbes) Geological Survey of Canada, Bedford Institute of Oceanography [email protected], tel: 902-426-0652 Welcome to Breakup 2017 You may also want to check out the Mackenzie-Beaufort Breakup group on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/groups/1745524288993851/). This year, in addition to sharing the newsletter to our mailing list of >370 addresses, we are posting the newsletters on the CACCON (Circum-Arctic Coastal Communities KnOwledge Network) website. You can find them at https://www.caccon.org/mackenzie-beaufort-break-up-newsletter/ Funding for our current breakup monitoring activity is from the Climate Change Geoscience Program of the Geological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada. Please let us know if you do not wish to receive these reports (contact info above) and we will take you off the list. For those of you living in the north, we welcome any observations of timing of events, extent of flooding, evidence of breakup, or anything out of the ordinary, and we thank you for all of the feedback received so far. For those interested in conditions further south, we recommend that you contact Angus Pippy (Water Survey of Canada) in order to receive his very useful High Water Report: contact Angus at 867-669-4774 or [email protected]. Water level data presented in our newsletters are courtesy of Environment Canada (Water Survey of Canada) and are derived from their real-time hydrometric data website at http://www.wateroffice.ec.gc.ca/index_e.html, which we acknowledge with thanks. -

The Reindeer Botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901–1977

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2012 The Reindeer Botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901–1977 Dathan, Wendy University of Calgary Press Dathan, Patricia Wendy. "The reindeer botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901-1977". Series: Northern Lights Series; 14, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49303 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Part One REINDEER SURVEY / EXPLORATION, 1901–1928 ° 160° 140° 120° 100° 80° 60° 40° 0 R U S S I A Wrangel Island 8 d n I a H l C A R C T I C O C E A N s K I U H e B A r C E ° e 0 e S R E E N L A N D 7 r m G i s D E N M A R K n e l Kotzebue g l S Barrow E E A B E A U F O R T S E A D Little Diomede Nome A Island V I S Devon Island S Unalakleet T Disko Resolute R Island A I Egedesminde T Banks Island Tuktoyaktuk B a Holsteinsborg L A S K A Fairbanks A Aklavik f f U S A i n Victoria I s Island l a n Godthaab d (Nuuk) Seward Norman Iqaluit Wells (Frobisher Bay) Y U K O N ° T E R R I T O R Y 60 O R T H W E S T E R R I T O R I E S HUDSON N T STRAIT Southampton Island UNGAVA NUNAVUT BAY NORTHWEST (after 1999) TERRITORIES (after 1999) H U D S O N B A Y B R I T I S H Churchill C O L U M B I A Fort McMurray Q U É B E C A L B E R T A M A N I T O B A S A S K A T - C H E W A N J A M E S B A Y Jasper Edmonton National 0° Park N T A R I O 5 0 500 1000 O Km Banff National Park Northern North America and Greenland: A. -

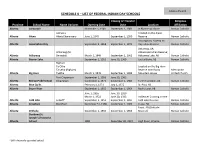

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories 2015

Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories 2015 www.nwtresearch.com This publication is a collaboration between the Aurora Research Institute, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Thank you to all who submitted a summary of research or photographs, and helped make this publication possible. Editors: Jonathon Michel, Jolie Gareis, Kristi Benson, Catarina Owen, Erika Hille Copyright © 2015 ISSN: 1205-3910 Printed in Yellowknife through the Aurora Research Institute Forward Welcome to the 2015 Compendium of Research in the Northwest Territories. I am pleased to present you with this publication, which is the product of an on-going collaboration between the Aurora Research Institute, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. This Compendium is a starting point to find out more information about research taking place in the NWT. In these pages you’ll find summaries of all licensed research projects that were conducted in the territory during the 2015 calendar year. You’ll also find the name and contact information for the lead researcher on each project. If there is a project that interests you, I urge you to contact the researcher to find out more about their work and results. You can also find more information online in the NWT Research Database. This is a publically-available, map- based online resource that can be accessed at http://data.nwtresearch.com/. The Database is continuously updated with new information, and was designed to make information about NWT research more accessible to the people and stakeholders living in our territory. -

Oral History Project Final Report

GWICH'IN TERRITORIAL PARK (CAMPBELL LAKE) ORAL HISTORY PROJECT FINAL REPORT Annie & Nap Norbert at T1thegeh chl' OR Gwl'eekajlchlt Elders: Lucy Adams Hyacinthe Andre Gabe Andre Antoine Andre Victor Allen Pierre Benoit Billy Day Harry Harrison Fred John Mary Kailek Annie Norbert Prepared for Dept. of Economic Development and Tourism (GNWT) Contract No. 312851 By Ingrid D. Kritsch, Gwich'in Social & Cultural Institute December 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................ 1 2. METHODOLOGY Methodology Used ........................................ 3 Elders Interviewed ........................................ 4 3. GWICHY A GWICH'IN TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND USE OF CAMPBELL LAKE ...................................... 10 Place Names . .1 0 Resources and Travel Routes .............................12 4. INUVIALUIT TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND USE OF CAMPBELL LAKE .............................................. 14 Place Names .............................................14 Resources and Travel Routes .............................14 5. PLACE NAMES COLLECTED FOR THE CAMPBELL LAKE AREA ......................................................... 16 Introduction ..............................................16 Gwichya Gwich'in, lnuvialuit and English Place Names ............................................ 17 6. RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................... 45 REFERENCES CITED ........................................... 49 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is the product of many people's efforts. First and -

Elders Antoine Andre Caroline Andre Gabe Andre Hyacinthe Andre Pierre Benoit Joan Nazon Annie Norbert Nap Norbert

GWICHYA GWICH’IN PLACE NAMES IN THE MACKENZIE DELTA, GWICH'IN SETTLEMENT AREA, N.W.T. Ingrid Kritsch & Alestine Andre GWICH'IN SOCIAL AND CULTURAL INSTITUTE Elders Antoine Andre Caroline Andre Gabe Andre Hyacinthe Andre Pierre Benoit Joan Nazon Annie Norbert Nap Norbert 1994 __________________________________________________________________ Copyright c 1994 Gwich'in Social and Cultural Institute Available in Canada from the Gwich'in Social and Cultural Institute, General Delivery, Tsiigehtchic, Northwest Territories, Canada X0E 0B0 Written by: Ingrid Kritsch and Alestine Andre Photo Credits: Ingrid Kritsch ISBN 1‐896337‐00‐7 __________________________________________________________ Dedicated to the Gwichya Gwich'in Elders who worked with us on the Gwichya Gwich'in Place Names Project in 1992, 1993, and 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Acknowledgements 1. INTRODUCTION . .1 2. METHODOLOGY . 7 3. PLACE NAMES . 11 4. SUMMARY . 53 5. RECOMMENDATIONS . 54 References Cited . 55 Appendix A Master Tape List . .56 Appendix B Map of Place Names . 57 Acknowledgements We greatfully acknowledge the financial support of the Beaufort‐Delta Divisional Board of Education; the Gwich'in Tribal Council; and the Secretary of State, Canada and the Department of Education, Culture and Employment, Government of the Northwest Territories. We would like to thank the following Gwichya Gwich'in Elders who shared their information and traditional knowledge about the areas they used in the Mackenzie Delta area. Their willingness, patience, and interest in teaching and passing on this information will preserve this knowledge for future generations. Mahsi' choo! Antoine (Tony) Andre Caroline Andre Gabe Andre Hyacinthe Andre Pierre Benoit Joan Nazon Annie Norbert Nap Norbert We would also like to thank Tommy Wright of Inuvik for sharing his extensive knowledge about the history of the Delta and for clarifying the many questions that arose.