May/June 20002000 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Should Functional Constituency Elections in the Legislative Council Be

Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Liberal Studies Independent Enquiry Study Report Standard Covering Page (for written reports and short written texts of non-written reports starting from 2017) Enquiry Question: Should Functional Constituency elections in the Legislative Council be abolished? Year of Examination: Name of Student: Class/ Group: Class Number: Number of words in the report: 3162 Notes: 1. Written reports should not exceed 4500 words. The reading time for non-written reports should not exceed 20 minutes and the short written texts accompanying non-written reports should not exceed 1000 words. The word count for written reports and the short written texts does not include the covering page, the table of contents, titles, graphs, tables, captions and headings of photos, punctuation marks, footnotes, endnotes, references, bibliography and appendices. 2. Candidates are responsible for counting the number of words in their reports and the short written texts and indicating it accurately on this covering page. 3. If the Independent Enquiry Study Report of a student is selected for review by the School-Based Assessment System, the school should ensure that the student’s name, class/ group and class number have been deleted from the report before submitting it to the Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority. Schools should also ensure that the identities of both the schools and students are not disclosed in the reports. For non-written reports, the identities of the students and schools, including the appearance of the students, should be deleted. Sample 1 Table of Contents A. Problem Definition P.3 B. Relevant Concepts and Knowledge/ Facts/ Data P.5 C. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 18

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 18 November 2010 2357 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 18 November 2010 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. 2358 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 18 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. THE HONOURABLE LEE WING-TAT DR THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. -

The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES The 2004 Legislative Council Elections and Implications for U.S. Policy toward Hong Kong Wednesday, September 15, 2004 Introduction: RICHARD BUSH Director, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies The Brookings Institution Presenter: SONNY LO SHIU-HING Associate Professor of Political Science University of Waterloo Discussant: ELLEN BORK Deputy Director Project for the New American Century [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM A TAPE RECORDING.] THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036 202-797-6307 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. BUSH: [In progress] I've long thought that politically Hong Kong plays a very important role in the Chinese political system because it can be, I think, a test bed, or a place to experiment on different political forums on how to run large Chinese cities in an open, competitive, and accountable way. So how Hong Kong's political development proceeds is very important for some larger and very significant issues for the Chinese political system as a whole, and therefore the debate over democratization in Hong Kong is one that has significance that reaches much beyond the rights and political participation of the people there. The election that occurred last Sunday is a kind of punctuation mark in that larger debate over democratization, and we're very pleased to have two very qualified people to talk to us today. The first is Professor Sonny Lo Shiu-hing, who has just joined the faculty of the University of Waterloo in Canada. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/CA LC Paper No. CB(2)133/12-13 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Constitutional Affairs Minutes of special meeting held on Saturday, 19 May 2012, at 9:00 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Dr Hon Margaret NG Hon CHEUNG Man-kwong Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, SBS, JP Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBM, GBS, JP Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon LEE Wing-tat Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, BBS, JP Dr Hon LAM Tai-fai, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, JP Hon IP Kwok-him, GBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Dr Hon Samson TAM Wai-ho, JP Hon Alan LEONG Kah-kit, SC Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Members : Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH absent Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC - 2 - Hon CHIM Pui-chung Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, BBS Hon WONG Yuk-man Public Officers : Sessions One to Three attending Office of the Chief Executive-elect Mrs Fanny LAW FAN Chiu-fun Head of the Chief Executive-elect's Office Ms Alice LAU Yim Secretary-General of the Chief Executive-elect's Office Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau Mr -

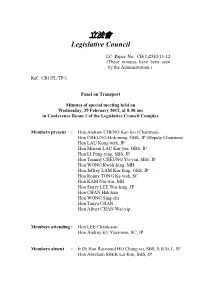

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration )

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(1)2583/11-12 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration ) Ref : CB1/PL/TP/1 Panel on Transport Minutes of special meeting held on Wednesday, 29 February 2012, at 8:30 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo (Chairman) Hon CHEUNG Hok-ming, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon LAU Kong-wah, JP Hon Miriam LAU Kin-yee, GBS, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, SBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, SBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-hing, MH Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon KAM Nai-wai, MH Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan Hon WONG Sing-chi Hon Tanya CHAN Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Members attending : Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Members absent : Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, SBS, S.B.St.J., JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, SBS, JP - 2 - Hon IP Wai-ming, MH Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Public Officers : Agenda item I attending Mr YAU Shing-mu, JP Under Secretary for Transport and Housing Miss Petty LAI Chun-yee Principal Assistant Secretary (Transport) 6 Transport and Housing Bureau Miss Cinderella LAW Fung-ping, JP Assistant Commissioner/Administration & Licensing Transport Department Mr Stephen Harvey VERRALLS Chief Superintendent of Police (Traffic) Hong Kong Police Force Attendance by : Agenda item I invitation Individual Mr Martin OEI Political Commentator Hong Kong Christian Institute Mr Andrew SHUM Wai-nam Programme Secretary (Social Concern) Individual Mr Paul ZIMMERMAN Southern -

Volume 13 No.1 Jan 2019 Produced by Design and Production Services UP

CityU Design and Production Services UP Volume 13 No.1 Jan 2019 produced by The Editorial Board would like to thank Agnes Kwok, Judy Xu as well as members of staff who helped in the preparation of the Newsletter. Dr Peter Chan (Editor in Chief), Ms Laveena Mahtani, Dr He Tianxiang Content Volume 13 No. 1 ∙ Jan 2019 1 MESSAGE FROM DEAN 2 SCHOOL EVENTS 3 RESEARCH CENTRES 4 STUDENT ACHIEVEMENTS 5 STAFF ACHIEVEMENTS Published by School of Law, CityU, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong Designed and printed by City University of Hong Kong Press Please send your comments to [email protected] ©2018 CityU School of Law. All rights reserved. Volume 13 No. 1 ∙ January 2019 1 Message from Dean CityU School of Law is constantly reviewing its initiatives to further Our School has signed enhance the quality of legal education that we have been providing collaborative agreements with for more than thirty years. We have established expertise in Common the Europe-Asia Research Law, Chinese Law and Comparative Law. An emphasis on arbitration Institute of Aix-Marseille and mediation has also remained a crucial fixture. In addition, University, the University Paris we have built a good reputation in a wide range of areas, ranging 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne in France, from commercial law to public law. We have the only commercial and Université de Fribourg in and maritime law centre in Hong Kong promoting research and Switzerland. Selected students providing educational opportunities to scholars, lawyers and business will study at the partner professionals. We also launched the Human Rights Law and Policy universities and obtain two Forum (HRLF) in September last year. -

One Country, Two Legal Systems (Crowley Report)

ONE COUNTRY, TWO LEGAL SYSTEMS? TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................1 A. Overview .....................................................................................................................................3 I. PRESERVING THE RULE OF LAW.............................................................................................4 A. The Rule of Law..........................................................................................................................5 1. General International Standards...............................................................................................5 2. The Sino-British Joint Declaration ..........................................................................................7 B. Implementing International Commitments: Hong Kong and the Basic Law ............................8 C. The Right of Abode Decisions ..................................................................................................10 1. Background ............................................................................................................................10 2. The Court of Final Appeal’s Decisions .................................................................................12 a. Article 158: The Reference Issue......................................................................................12 b. Articles 22 and 24 of the Basic Law..................................................................................15 -

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China's December 2007

Order Code RS22787 January 10, 2008 Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China’s December 2007 Decision Michael F. Martin Analyst in Asian Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Summary The prospects for democratization in Hong Kong became clearer following a decision of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress (NPCSC) on December 29, 2007. The NPCSC’s decision effectively set the year 2017 as the earliest date for the direct election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the year 2020 as the earliest date for the direct election of all members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (Legco). However, ambiguities in the language used by the NPCSC have contributed to differences in interpretation of its decision. According to Hong Kong’s current Chief Executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the decision sets a clear timetable for democracy in Hong Kong. However, representatives of Hong Kong’s “pro- democracy” parties believe the decision includes no solid commitment to democratization in Hong Kong. The NPCSC’s decision also established some guidelines for the process of election reform in Hong Kong, including what can and cannot be altered in the 2012 elections. Since China established the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) on July 1, 1997, there have been questions about when and how the democratization of Hong Kong will take place.1 At present, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is selected by an “Election Committee” of 800 largely appointed people, and its Legislative Council (Legco) consists of 30 members elected by universal suffrage in five geographic districts and 30 members selected by 28 “functional constituencies” representing various important sectors. -

24 May 2002 Mr Simon Ip Shing Hing by POST President Law Society Of

LC Paper No. CB(2)2098/01-02(01) 24 May 2002 Mr Simon Ip Shing Hing BY POST President Law Society of Hong Kong 3/F Wing On House 71 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong Dear Simon, Re: Clause 105 Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill The attached comments have been received from a member of the Law Society on the proposed amendments to section 6 of the Legal Practitioners Ordinance. I should be grateful for your response to the concerns expressed, so that both the comments and your response may be put before the Bills Committee for members’ consideration. By copy of this letter, I am also inviting the Administration's response. With best regards. Yours sincerely, MN/eh Margaret Ng cc: Mr Michael Scott, Department of Justice Clerk, Bills Committee Statute Law (Misc Provisions) Bill Comments on Clause 105, Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill This amendment will give the Law Society power to make rules to regulate/prevent the practitioners (whom the Law Society does not like) from opening a small law firm. The present rule is the Practising Certificate (Solicitors) (Grounds for Refusal) Rules (copy attached), which set out a number of factors to refuse the issue of a practicing certificate. If the amendment is passed, the Law Society Council will have unrestricted wide power to refuse the issue of or impose any conditions on the practicing certificate. This will cause an unfair situation whereby a solicitor can be refused an unconditional practicing certificate for reason that he has done some misconduct (even on a very trivial matters) and for which he has got severe punishment. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)156/06-07 Ref : CB2/PS/4/04 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Subcommittee on Review of Existing Statutory Provisions on Search and Seizure of Journalistic Material Minutes of meeting held on Thursday, 4 May 2006, at 2:30 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon James TO Kun-sun (Chairman) present Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon Margaret NG Hon Howard YOUNG, SBS, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Member : Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC attending Members : Hon Albert HO Chun-yan absent Dr Hon Philip WONG Yu-hong, GBS Hon WONG Yung-kan, JP Hon Daniel LAM Wai-keung, BBS, JP Public Officers : Mrs Apollonia LIU attending Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Miss Rosalind CHEUNG Assistant Secretary for Security Mr Kevin Paul ZERVOS, SC Senior Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions Department of Justice - 2 - Ms Roxana CHENG Senior Assistant Solicitor General Department of Justice Mr Alfred MA Chief Superintendent of Police (Crime Headquarters) (Crime Wing) Ms Bessie HO Principal Investigator/Operations Independent Commission Against Corruption Clerk in : Mrs Sharon TONG attendance Chief Council Secretary (2)1 Staff in : Mr LEE Yu-sung attendance Senior Assistant Legal Adviser 1 Mr Raymond LAM Senior Council Secretary (2)5 Action I. Meeting with the Administration (LC Paper No. CB(2)1858/05-06(01)) Principal Assistant Secretary for Security (PAS(S)) briefed members on the Administration's paper entitled "Review/Appeal Mechanism". 2. Dr LUI Ming-wah asked about the timing and nature of the four cases referred to in paragraph 5 of the Administration's paper. -

香港特別行政區排名名單 the Precedence List of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

二零二一年九月 September 2021 香港特別行政區排名名單 THE PRECEDENCE LIST OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 1. 行政長官 林鄭月娥女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS The Chief Executive The Hon Mrs Carrie LAM CHENG Yuet-ngor, GBM, GBS 2. 終審法院首席法官 張舉能首席法官,大紫荊勳賢 The Chief Justice of the Court of Final The Hon Andrew CHEUNG Kui-nung, Appeal GBM 3. 香港特別行政區前任行政長官(見註一) Former Chief Executives of the HKSAR (See Note 1) 董建華先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon TUNG Chee Hwa, GBM 曾蔭權先生,大紫荊勳賢 The Hon Donald TSANG, GBM 梁振英先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon C Y LEUNG, GBM, GBS, JP 4. 政務司司長 李家超先生,SBS, PDSM, JP The Chief Secretary for Administration The Hon John LEE Ka-chiu, SBS, PDSM, JP 5. 財政司司長 陳茂波先生,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, MH, JP The Financial Secretary The Hon Paul CHAN Mo-po, GBM, GBS, MH, JP 6. 律政司司長 鄭若驊女士,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, SC, JP The Secretary for Justice The Hon Teresa CHENG Yeuk-wah, GBM, GBS, SC, JP 7. 立法會主席 梁君彥議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The President of the Legislative Council The Hon Andrew LEUNG Kwan-yuen, GBM, GBS, JP - 2 - 行政會議非官守議員召集人 陳智思議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Convenor of the Non-official The Hon Bernard Charnwut CHAN, Members of the Executive Council GBM, GBS, JP 其他行政會議成員 Other Members of the Executive Council 史美倫議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Laura CHA SHIH May-lung, GBM, GBS, JP 李國章議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP Prof the Hon Arthur LI Kwok-cheung, GBM, GBS, JP 周松崗議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon CHOW Chung-kong, GBM, GBS, JP 羅范椒芬議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon Mrs Fanny LAW FAN Chiu-fun, GBM, GBS, JP 黃錦星議員,GBS, JP 環境局局長 The Hon WONG Kam-sing, GBS, JP Secretary for the Environment # 林健鋒議員,GBS, JP The Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP 葉國謙議員,大紫荊勳賢,GBS, JP The Hon