Projected Distribution Shifts and Protected Area Coverage of Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution, Natural History and Conservation Status of Two

Bird Conservation International (2008) 18:331–348. ª BirdLife International 2008 doi:10.1017/S0959270908007491 Printed in the United Kingdom Distribution, natural history and conservation status of two endemics of the Bolivian Yungas, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, A. BENNETT HENNESSEY, MICHAEL KESSLER and VI´CTOR H. GARCI´A-SOLI´Z Summary Since their description in the first half of the 20th century by M. A. Carriker, Bolivian Recurvebill Simoxenops striatus and Yungas Antwren Myrmotherula grisea have been regarded as extremely poorly known endemics of the Bolivian Yungas and adjacent humid foothill forests. They are considered ‘Vulnerable’ under the IUCN criteria of small population, predicted population decline (criterion C2a) and, in the case of Bolivian Recurvebill, small extent of occurrence (criteria B1a+b). Here we summarise the information published to date and present extensive new data on the distribution (including the first records for extreme southeast Peru), natural history, population size and conservation status of both species based on field work in the Bolivian Andes over the past 12 years. Both species primarily inhabit the understorey of primary and mid-aged to older regenerating forest and regularly join mixed-species foraging flocks of insectivorous birds. Bolivian Recurvebill has a strong preference for Guadua bamboo, but it is not an obligate bamboo specialist and persists at often much lower densities in forests without Guadua. Yungas Antwren seems to have a preference for dense, structurally complex under- storey, often with Chusquea bamboo. Both species are distributed much more continuously at altitudes of mostly 600–1,500 m, occupy a greater variety of forest types (wet, humid, semi- deciduous forest) and have a much greater population size than previously thought. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Bolivia: the Andes and Chaco Lowlands

BOLIVIA: THE ANDES AND CHACO LOWLANDS TRIP REPORT OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2017 By Eduardo Ormaeche Blue-throated Macaw www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Bolivia, October/November 2017 Bolivia is probably one of the most exciting countries of South America, although one of the less-visited countries by birders due to the remoteness of some birding sites. But with a good birding itinerary and adequate ground logistics it is easy to enjoy the birding and admire the outstanding scenery of this wild country. During our 19-day itinerary we managed to record a list of 505 species, including most of the country and regional endemics expected for this tour. With a list of 22 species of parrots, this is one of the best countries in South America for Psittacidae with species like Blue-throated Macaw and Red-fronted Macaw, both Bolivian endemics. Other interesting species included the flightless Titicaca Grebe, Bolivian Blackbird, Bolivian Earthcreeper, Unicolored Thrush, Red-legged Seriema, Red-faced Guan, Dot-fronted Woodpecker, Olive-crowned Crescentchest, Black-hooded Sunbeam, Giant Hummingbird, White-eared Solitaire, Striated Antthrush, Toco Toucan, Greater Rhea, Brown Tinamou, and Cochabamba Mountain Finch, to name just a few. We started our birding holiday as soon as we arrived at the Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, birding the grassland habitats around the terminal. Despite the time of the day the airport grasslands provided us with an excellent introduction to Bolivian birds, including Red-winged Tinamou, White-bellied Nothura, Campo Flicker, Chopi Blackbird, Chotoy Spinetail, White Woodpecker, and even Greater Rhea, all during our first afternoon. -

Peru: from the Cusco Andes to the Manu

The critically endangered Royal Cinclodes - our bird-of-the-trip (all photos taken on this tour by Pete Morris) PERU: FROM THE CUSCO ANDES TO THE MANU 26 JULY – 12 AUGUST 2017 LEADERS: PETE MORRIS and GUNNAR ENGBLOM This brand new itinerary really was a tour of two halves! For the frst half of the tour we really were up on the roof of the world, exploring the Andes that surround Cusco up to altitudes in excess of 4000m. Cold clear air and fantastic snow-clad peaks were the order of the day here as we went about our task of seeking out a number of scarce, localized and seldom-seen endemics. For the second half of the tour we plunged down off of the mountains and took the long snaking Manu Road, right down to the Amazon basin. Here we traded the mountainous peaks for vistas of forest that stretched as far as the eye could see in one of the planet’s most diverse regions. Here, the temperatures rose in line with our ever growing list of sightings! In all, we amassed a grand total of 537 species of birds, including 36 which provided audio encounters only! As we all know though, it’s not necessarily the shear number of species that counts, but more the quality, and we found many high quality species. New species for the Birdquest life list included Apurimac Spinetail, Vilcabamba Thistletail, Am- pay (still to be described) and Vilcabamba Tapaculos and Apurimac Brushfnch, whilst other montane goodies included the stunning Bearded Mountaineer, White-tufted Sunbeam the critically endangered Royal Cinclodes, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Peru: From the Cusco Andes to The Manu 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com These wonderful Blue-headed Macaws were a brilliant highlight near to Atalaya. -

PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept

Tropical Birding Trip Report PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept. 2015 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour PERU: MANU and MACHU PICCHU th th 29 August – 16 September 2015 Tour Leader: Jose Illanes Andean Cock-of-the-rock near Cock-of-the-rock Lodge! Species highlighted in RED are the ones illustrated with photos in this report. INTRODUCTION Not everyone is fortunate enough to visit Peru; a marvelous country that boasts a huge country bird list, which is second only to Colombia. Unlike our usual set departure, we started out with a daylong extension to Lomas de Lachay first, before starting out on the usual itinerary for the main tour. On this extra day we managed to 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report PERU: Manu and Machu Picchu Aug-Sept. 2015 find many extra birds like Peruvian Thick-knee, Least Seedsnipe, Peruvian Sheartail, Raimondi’s Yellow- Finch and the localized Cactus Canastero. The first site of the main tour was Huacarpay Lake, near the beautiful Andean city of Cusco (accessed after a short flight from Lima). This gave us a few endemic species like Bearded Mountaineer and Rusty-fronted Canastero; along with other less local species like Many-colored Rush-tyrant, Plumbeous Rail, Puna Teal, Andean Negrito and Puna Ibis. The following day we birded along the road towards Manu where we picked up birds like Peruvian Sierra-Finch, Chestnut-breasted Mountain-Finch, Spot-winged Pigeon, and a beautiful Peruvian endemic in the form of Creamy-crested Spinetail. We also saw Yungas Pygmy-Owl, Black-faced Ibis, Hooded and Scarlet-bellied Mountain- Tanagers, Red-crested Cotinga and the gorgeous Grass-green Tanager. -

First Ornithological Inventory and Conservation Assessment for the Yungas Forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia

Bird Conservation International (2005) 15:361–382. BirdLife International 2005 doi:10.1017/S095927090500064X Printed in the United Kingdom First ornithological inventory and conservation assessment for the yungas forests of the Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes, Cochabamba, Bolivia ROSS MACLEOD, STEVEN K. EWING, SEBASTIAN K. HERZOG, ROSALIND BRYCE, KARL L. EVANS and AIDAN MACCORMICK Summary Bolivia holds one of the world’s richest avifaunas, but large areas remain biologically unexplored or unsurveyed. This study carried out the first ornithological inventory of one of the largest of these unexplored areas, the yungas forests of Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes. A total of 339 bird species were recorded including 23 restricted-range, four Near-Threatened, two globally threatened, one new to Bolivia and one that may be new to science. The study extended the known altitudinal ranges of 62 species, 23 by at least 500 m, which represents a substantial increase in our knowledge of species distributions in the yungas, and illustrates how little is known about Bolivia’s avifauna. Species characteristic of, or unique to, three Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs) were found. The Cordilleras Cocapata and Mosetenes are a stronghold for yungas endemics and hold large areas of pristine Bolivian and Peruvian Upper and Lower Yungas habi- tat (EBAs 54 and 55). Human encroachment is starting to threaten the area and priority conser- vation actions, including designation as a protected area and designation as one of Bolivia’s first Important Bird Areas, are recommended. Introduction Bolivia holds the richest avifauna of any landlocked country. With a total of 1,398 species (Hennessey et al. -

The Envira Amazonia Project a Tropical Forest Conservation Project in Acre, Brazil

The Envira Amazonia Project A Tropical Forest Conservation Project in Acre, Brazil Prepared by Brian McFarland from: 853 Main Street East Aurora, New York - 14052 (240) 247-0630 With significant contributions from: James Eaton, TerraCarbon JR Agropecuária e Empreendimentos EIRELI Pedro Freitas, Carbon Securities Ayri Rando, Independent Community Specialist A Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standard Project Implementation Report TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER PAGE .................................................................................................................... Page 4 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………..……………. Page 5 GENERAL SECTION G1. Project Goals, Design and Long-Term Viability …………………………….………. Page 6 A. Project Overview 1. Project Proponents 2. Project’s Climate, Community and Biodiversity Objectives 3. Project Location and Parameters B. Project Design and Boundaries 4. Project Area and Project Zone 5. Stakeholder Identification and Analysis 6. Communities, Community Groups and Other Stakeholders 7. Map Identifying Locations of Communities and Project 8. Project Activities, Outputs, Outcomes and Impacts 9. Project Start Date, Lifetime and GHG Accounting Period C. Risk Management and Long-Term Viability 10. Natural and Human-Induced Risks 11. Enhance Benefits Beyond Project Lifetime 12. Financial Mechanisms Adopted G2. Without-Project Land Use Scenario and Additionality ………………..…………….. Page 52 1. Most Likely Land-Use Scenario 2. Additionality of Project Benefits G3. Stakeholder Engagement ……………………………………………………………. Page 57 A. Access to Information 1. Accessibility of Full Project Documentation 2. Information on Costs, Risks and Benefits 3. Community Explanation of Validation and Verification Process B. Consultation 4. Community Influence on Project Design 5. Consultations Directly with Communities C. Participation in Decision-Making and Implementation 6. Measures to Enable Effective Participation D. Anti-Discrimination 7. Measures to Ensure No Discrimination E. Feedback and Grievance Redress Procedure 8. -

Machu Picchu & Abra Malaga, Peru II 2017

Field Guides Tour Report Machu Picchu & Abra Malaga, Peru II 2017 Aug 3, 2017 to Aug 12, 2017 Jesse Fagan & Cory Gregory For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The view from the west slope of Abra Malaga takes your breath away! Photo by guide Cory Gregory. Saying that the Cusco region of Peru has “a lot to offer” is a bit of an understatement! Besides the intensely rich human history of the Inca and the ruins that still endure, this part of Peru has an impressive avian diversity highlighted by a lengthy list of species found nowhere else on the planet. Our tour to this region, graced with superb weather, some phenomenal birding, and a fun bunch of birders, made this a pleasant trip and one we hope you enjoyed. Although our tour started in Lima, our real birding began after our early-morning flight to Cusco. Carlos and Lucretia (and some hot coca tea) met us at the airport before we headed off to Huacarpay Lake. The lake yielded a wealth of new birds like Puna and Yellow-billed teal, Yellow-billed Pintail, the sneaky Wren-like Rushbird, and the gaudy but secretive Many-colored Rush-Tyrants. We saw some specialties, too, like the Peruvian endemic Rusty- fronted Canastero, the shy Streak-fronted Thornbird, and even a couple of ground-tyrants like Spot-billed and Rufous-naped. The grounds of our hotel in Ollantaytambo yielded even more targets like the fan favorite Bearded Mountaineer, Green-tailed Trainbearer, Golden-billed Saltator, and Black-backed Grosbeak. -

Rediscovery of the Bolivian Recurvebill with Notes on Other Little

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 173 FOSTER, M. S. 1976. Nesting biology of the Long-tailed Manakin. Wilson Bull. 88:400- 420. -. 1987. Delayed maturation, neoteny, and social system differences in two manakins of the genus Chiroxiphia. Evolution 41:547-558. IHWNG, H. VON. 1900. Cat&logo critico-comparative dos ninhos e ovos das Aves do Brazil. Rev. Mus. Paul. 4: 19 l-300. -. 1902. Contribuiqoes para o conhecimento da Omithologia de S. Paulo. Rev. Mus. Paul. 5261-326. LEVEY, D. J. 1988. Spatial and temporal variation in Costa Rican fruit-eating bird abun- dance. Ecol. Monogr. 58:25 l-269. MARINI, M. A. 1989. Sele@o de habitat e socialidade em Antilophia galeata (Aves: Pipri- dae). M.Sc. thesis, Univ. de Brasilia, Brasilia, Brazil. MEYER DE SCHAUENSEE,R. M. 1970. A guide to the birds of South America. Livingston Publ., Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. PRUM, R. 0. 1989. Phylogenetic analysis of the morphological and behavioral evolution of the Neotropical manakins (Aves: Pipridae). Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. RATTER, J. A. 1980. Notes on the vegetation of Fazenda Agua Limpa (Brasilia, DF, Brasil). Royal Bot. Garden, Edinburgh, Scotland. SICK, H. 1967. Courtship behavior in the Manakins (Pipridae); a review. Living Bird 6: 5-22. SKUTCH, A. F. 1949. Life history of the Yellow-thighed Manakin. Auk 66: l-24. -. 1969. Life histories of Central American birds. III. Pac. Coast Avifauna 35:1- 580. SNOW, D. W. 1962. A field study of the Black and White Manakin, Manacus manacus, in Trinidad. Zoologica 47:65-104. WORTHINGTON, A. 1982. Population sizes and breeding rhythms of two species of Man- akins in relation to food supply. -

Seasonality and Elevational Migration in an Andean Bird Community

SEASONALITY AND ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION IN AN ANDEAN BIRD COMMUNITY _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CHRISTOPHER L. MERKORD Dr. John Faaborg, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2010 © Copyright by Christopher L. Merkord 2010 All Rights reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled ELEVATIONAL MIGRATION OF BIRDS ON THE EASTERN SLOPE OF THE ANDES IN SOUTHEASTERN PERU presented by Christopher L. Merkord, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor John Faaborg Professor James Carrel Professor Raymond Semlitsch Professor Frank Thompson Professor Miles Silman For mom and dad… ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was completed with the mentoring, guidance, support, advice, enthusiasm, dedication, and collaboration of a great many people. Each chapter has its own acknowledgments, but here I want to mention the people who helped bring this dissertation together as a whole. First and foremost my parents, for raising me outdoors, hosting an endless stream of squirrels, snakes, lizards, turtles, fish, birds, and other pets, passing on their 20-year old Spacemaster spotting scope, showing me every natural ecosystem within a three day drive, taking me on my first trip to the tropics, putting up with all manner of trouble I’ve gotten myself into while pursuing my dreams, and for offering my their constant love and support. Tony Ortiz, for helping me while away the hours, and for sharing with me his sense of humor. -

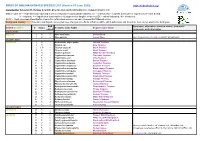

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

PEREGRINE BIRD TOURS BOLIVIA 10 – 30 November 2018 TOUR

PEREGRINE BIRD TOURS BOLIVIA 10 – 30 November 2018 TOUR REPORT LEADERS: Chris Doughty and Sandro Valdez. GROUP MEMBERS: Rebecca Albury, Graham Barwell, Paul Handreck, Elvyne Hogan, Max James and Jann Skinner. This little known and sparsely populated country, has the highest avian diversity of any land-locked country on the planet, the birding was breathtakingly exciting and produced a suite of new and interesting birds, on every day of the tour. We did particularly well with birds of prey, observing a good number of rarely seen species, which included King Vulture, Andean Condor, Swallow-tailed, Slender-billed and Double-toothed Kites, Great Black Hawk, Solitary Eagle and White-rumped and Zone-tailed Hawks. Bolivia is an outstanding destination to observe New World parrots, and we observed a total of 22 separate species of parrots, and all of them were seen particularly well. Five of them were Macaws, including two large and exceedingly rare and endemic species of Macaws, the Blue-throated and the Chestnut-fronted, which we saw splendidly well. Throughout the tour we explored a wide variety of habitats, we birded steamy Amazonian lowland rainforest, savanna grasslands, cactus-studded hillsides, elfin cloud forest and the Altiplano, high alpine plateaus, situated above the tree line, dotted with numerous small lakes. Highlights amongst the 470 species of birds we observed, were many and varied, we saw 13 of the 19 endemic birds of Bolivia and here are just some of the many highlights; Huayco Tinamou, White-bellied Nothura, the flightless Titicaca Grebe, Whistling Heron, Rufescent Tiger Heron, Plumbeous Ibis, Hoatzin, Giant Coot, Sungrebe, Red-legged Seriema, Wilson's Phalarope, Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe, Cliff, Grey-hooded and Andean Parakeets, Tucuman Amazon, Tawny-bellied Screech Owl, Andean Swift and no less than 23 species of dazzling hummingbirds.