A History and Assessment of Jonathan Larson's Rent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Dstprogram-Ticktickboom

SCOTTSDALE DESERT STAGES THEATRE PRESENTS May 7 – 16, 2021 DESERT STAGES THEATRE SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA PRESENTS TICK, TICK...BOOM! Book, Music and Lyrics by Jonathan Larson David Auburn, Script Consultant Vocal Arrangements and Orchestrations by Stephen Oremus TICK, TICK...BOOM! was originally produced off-Broadway in June, 2001 by Victoria Leacock, Robyn Goodman, Dede Harris, Lorie Cowen Levy, Beth Smith Co-Directed by Mark and Lynzee 4man TICK TICK BOOM! is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME TO DST Welcome to Desert Stages Theatre, and thank you for joining us at this performance of Jonathan Larson’s TICK, TICK...BOOM! The talented casts that will perform in this show over the next two weekends include some DST “regulars” - familiar faces that you have seen here before - as well as actors who are brand new to the DST stage. Thank you to co- directors Mark and Lynzee 4man who were the natural choices to co- direct (and music direct and choreograph) a rock musical that represents our first teen/young adult production in more than a year. They have worked tirelessly with an extremely skilled team of actors, designers, and crew members to bring you this beautiful show, and everyone involved has enjoyed the process very much. We continue our COVID-19 safety protocols and enhanced cleaning measures to keep you and our actors safe. In return, we ask that you kindly wear your mask the entire time you are in the theatre, and stay in your assigned seat. -

Jonathan Larson

Famous New Yorker Jonathan Larson As a playwright, Jonathan Larson could not have written a more dramatic climax than the real, tragic climax of his own story, one of the greatest success stories in modern American theater history. Larson was born in White Plains, Westchester County, on February 4, 1960. He sang in his school choir, played tuba in the band, and was a lead actor in his high school theater company. With a scholarship to Adelphi University, he learned musical composition. After earning a Fine Arts degree, Larson had to wait tables, like many a struggling artist, to pay his share of the rent in a poor New York City apartment while honing his craft. In the 1980s and 1990s, Larson worked in nearly every entertainment medium possible. He won early recognition for co-writing the award-winning cabaret show Saved!, but his rock opera Superbia, inspired by The original Broadway Rent poster George Orwell’s novel 1984, was never fully staged in Larson’s lifetime. Scaling down his ambitions, he performed a one-man show called tick, tick … BOOM! in small “Off -Broadway” theaters. In between major projects, Larson composed music for children’s TV shows, videotapes and storybook cassette tapes. In 1989, playwright Billy Aronson invited Larson to compose the music for a rock opera inspired by La Bohème, a classical opera about hard-living struggling artists in 19th century Paris. Aronson wanted to tell a similar story in modern New York City. His idea literally struck Larson close to home. Drawing on his experiences as a struggling musician, as well as many friends’ struggles with the AIDS virus, Larson wanted to do all the writing himself. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Lucas Richman Symphony's THIS WILL BE OUR REPLY to Make West Coast Premiere

West End Off-Broadway United States International Entertainment Log In Los Angeles Los Angeles Sections Shows Chat Boards Jobs Students Video Industry Lucas Richman Symphony's THIS WILL BE Hot Stories BroadwayWorld TV OUR REPLY to Make West Coast Premiere by BWW News Desk Jul. 28, 2019 Tweet Share Reviews: INTO THE WOODS at the Hollywood Bowl GRAMMY award-winning conductor/composer Lucas Richman's three-movement symphony, This Will Be Our Reply will make its West Coast debut on August 17 in Los COME FROM AWAY's Beck Angeles. Conductor Noreen Green will lead the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony in Welcomes Chicago To Th performance of the piece as part of the Friendship & Harmony concert at 8 p.m., Saturday, August 17, at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. EXCLUSIVE: Inside Rehearsal LOS ANGELES SHOWS For INTO THE WOODS at the Symphony: This Will Be Our Reply is inspired by Leonard Bernstein's "An Artist's Hollywood Bowl Choice Response to Violence." After President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Beverly Hills composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein spoke at the United Jewish Appeal of 9/29) PHO CAST Greater New York's annual fundraising event, the twenty-fth "Night of Stars" in New TBT: FIRST DATE Makes Its Firs York. The event became a memorial to President Kennedy. Bernstein's words included On Broadway! (mostly) the remarks, "This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more Photos: Inside Opening DOG DAY beautifully, more devotedly than ever before." Night of INTO THE WOODS at the Hollywood Bowl Summer Upstairs at V Lucas Richman received special permission from the Leonard Bernstein Ofce to 8/12) PHO compose the three-movement symphony inspired by Bernstein's words, which resonate just as much today as they did more than a half-century ago. -

La-Boheme-Study-Guide-Reduced.Pdf

VANCOUVER OPERA PRESENTS LA BOHÈME Giacomo Puccini STUDY GUIDE OPERA IN FOUR ACTS By Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on Henri Murger’s novel Scènes de la Vie de bohème. In Italian with English Surtitles™ CONDUCTOR Judith Yan DIRECTOR Renaud Doucet QUEEN ELIZABETH THEATRE February 14, 16, 19 & 21at 7:30PM | February 24 at 2PM DRESS REHEARSAL Tuesday, February 12 at 7PM OPERA EXPERIENCE Tuesday, February 19 and 21 at 7:30PM EDUCATION LA BOHÈME VANCOUVER OPERA | STUDY GUIDE LA BOHÈME Giacomo Puccini CAST IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE MARCELLO, A PAINTER Phillip Addis RODOLFO, A POET Ji-Min Park COLLINE, A PHILOSOPHER Neil Craighead SCHAUNARD, A MUSICIAN Geoffrey Schellenberg BENOIT, A LANDLORD J. Patrick Raftery MIMI, A SEAMSTRESS France Bellemare PLUM SELLER Wade Nott PARPIGNOL, A TOY SELLER William Grossman MUSETTA, A WOMAN OF THE LATIN QUARTER Sharleen Joynt ALCINDORO, AN ADMIRER OF MUSETTA J. Patrick Raftery CUSTOMS OFFICER Angus Bell CUSTOMS SERGEANT Willy Miles-Grenzberg With the Vancouver Opera Chorus as habitués of the Latin Quarter, students, vendors, soldiers, waiters, and with the Vancouver Opera Orchestra. SCENIC DESIGNER / COSTUME DESIGNER André Barbe CHORUS DIRECTOR/ ASSOCIATE CONDUCTOR Leslie Dala CHILDREN’S CHORUS DIRECTOR / PRINCIPAL RÉPÉTITEUR Kinza Tyrrell LIGHTING DESIGNER Guy Simard WIG DESIGNER Marie Le Bihan MAKEUP DESIGNER Carmen Garcia COSTUME COORDINATOR Parvin Mirhady MUSICAL PREPARATION Tina Chang, Perri Lo* STAGE MANAGER Theresa Tsang ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Peter Lorenz ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGERS Marijka Asbeek Brusse, Michelle Harrison ASSISTANT LIGHTING DESIGNER Sara Smith ENGLISH SURTITLE™ TRANSLATIONS David Edwards Member of the Yulanda M. Faris Young Artist Program* The performance will last approximately 2 hours and 18 minutes. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2002 A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays. Bonny Ball Copenhaver East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Copenhaver, Bonny Ball, "A Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays." (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 632. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/632 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis by Bonny Ball Copenhaver May 2002 Dr. W. Hal Knight, Chair Dr. Jack Branscomb Dr. Nancy Dishner Dr. Russell West Keywords: Gender Roles, Feminism, Modernism, Postmodernism, American Theatre, Robbins, Glaspell, O'Neill, Miller, Williams, Hansbury, Kennedy, Wasserstein, Shange, Wilson, Mamet, Vogel ABSTRACT The Portrayal of Gender and a Description of Gender Roles in Selected American Modern and Postmodern Plays by Bonny Ball Copenhaver The purpose of this study was to describe how gender was portrayed and to determine how gender roles were depicted and defined in a selection of Modern and Postmodern American plays. -

La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Afterscènes Da La Vie De Bohème by Henri Murger

____________________ The Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 395th production La Bohème Opera in Four Acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Italian Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica AfterScènes da la vie de Bohème by Henri Murger David Effron,Conductor Tito Capobianco, Stage Director C. David Higgins, Set Designer Barry Steele, Lighting Designer Sondra Nottingham, Wig and Make-up Designer Vasiliki Tsuova, Chorus Master Lisa Yozviak, Children’s Chorus Master Christian Capocaccia, Italian Diction Coach Words for Music, Supertitle Provider Victor DeRenzi, Supertitle Translator _______________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Ninth Saturday Evening, November Tenth Friday Evening, November Sixteenth Saturday Evening, November Seventeenth Eight O’Clock Two Hundred Eighty-Fourth Program of the 2007-08 Season music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) The four Bohemians: Rodolfo, a poet. Brian Arreola, Jason Wickson Marcello, a painter . Justin Moore, Kenneth Pereira Colline, a philosopher . Max Wier, Miroslaw Witkowski Schaunard, a musician . Adonis Abuyen, Mark Davies Benoit, their landlord . .Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Mimi, a seamstress . Joanna Ruzsała, Jung Nan Yoon Two delivery boys . Nick Palmer, Evan James Snipes Parpignol, a toy vendor . Hong-Teak Lim Musetta, friend of Marcello . Rebecca Fay, Laura Waters Alcindoro, a state councilor . Joseph “Bill” Kloppenburg, Chaz Nailor Customs Guard . Nathan Brown Sergeant . .Cody Medina People of the Latin Quarter Vendors . Korey Gonzalez, Olivia Hairston, Wayne Hu, Kimberly Izzo, David Johnson, Daniel Lentz, William Lockhart, Cody Medina, Abigail Peters, Lauren Pickett, Shelley Ploss, Jerome Sibulo, Kris Simmons Middle Class . Jacqueline Brecheen, Molly Fetherston, Lawrence Galera, Chris Gobles, Jonathan Hilber, Kira McGirr, Justin Merrick, Kevin Necciai, Naomi Ruiz, Jason Thomas Elegant Ladies . -

Angled Parking Spaces Proposed for Prospect St. Prove Inefficient Mayor Mcdermott Says Goodbye, Thanks Westfield Residents Adjus

Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, June 23, 2005 OUR 115th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 25-2005 Periodical – Postage Paid at Westfield, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Andrew Skibitsky Takes Reigns As Mayor From Greg McDermott By MICHAEL POLLACK ber of the staff. My love and admiration here as friends and looked beside it.” Specially Written for The Westfield Leader for you are endless,” Mayor McDermott Speaking on election night Novem- WESTFIELD — Mayor Greg said. “To my four children, thanks for ber 2004 when the two were support- McDermott resigned this Tuesday, keeping up your end of the bargain. I ive of the defeated parking deck pro- after close to eight years as a Westfield know you are in the eye of the public, posal, Councilman Goldman said, public servant. Mayor McDermott and you made us proud.” “We almost became kindred spirits.” ended his tenure prematurely and is “All of us have dreams. I am one of First Ward Councilman Peter moving to Bernardsville, necessitat- the fortunate people to fulfill the Echausse, who wiped away tears as he ing his resignation prior to the end of dream. And it is the powerful sense of finished his speech, said he was “blessed his term on December 31, 2005. honor I still feel from when I first to know” the former mayor. “I wouldn’t Following the mayor’s resignation came on here. I’ve been blessed to be on the dais if it wasn’t for you. -

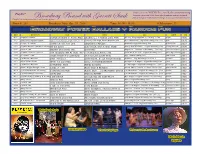

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack Free of Charge at Public Radio Exchange, > Prx.Org > Broadway Bound *Playlist Is Listed by Show (Disc), Not in Order of Play

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed by show (disc), not in order of play. Show #: 261 Broadcast Date: Oct. 29, 2016 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 23 Broadway Power Ballads + Random Fun Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 4:02 Stephen Sondheim Everybody Ought to Have a Maid Stadlen, L.J. + Nathan Lane, Mark A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Angel 1996 4/18/1996 - 1/4/1998. 715 Perf. One 1996 Tony Award: Best Actor - Nathan Lane. CDS Funny 8 1996 1/30/10 10/29/16 7:13 Ahlert/Young; Carmichael/Loesser; Finale: I'm Gonna Sit Right Down...; Two Sleepy People; I've Got My Company: Ken Page, Amelia McQueen, Nell Ain'tForum Misbehavin' - 1996 Revival Original Broadway Broadway Cast Cast-Disc 2 RCA 5/9/1978 - 2/21/1982. 1604 perf. Three 1978 Tony Awards: Best Musical; Best CDS Aint 0:04 10/14/067/7/07 1/17/09 3/27/10 11/26/113/15/14 10/29/16 Fingers Crossed;I Can't give You Anything…; It's a Sin To Linn-Baker, Ernie Sabella 1978 2/12 McHugh/Koehler; D Fields; Mayhew; Tell…;Honeysuckle Rose. Carter, Charlene Woodard, Andre De Shields Featured Actress - Nell Carter; Best Direction.