Memorable Canal Visits Shropshire Union Canal (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beginner's Guide to Boating on Inland Waterways

Ti r A Beginner’s Guide To Boating On Inland Waterways Take to the water with British Waterways and the National Rivers Authority With well over 4,000 km (2,500 miles) of rivers and canals to explore, from the south west of England up to Scotland, our inland waterways offer plenty of variety for both the casual boater and the dedicated enthusiast. If you have ever experienced the pleasures of 'messing about on boats', you will know what a wealth of scenery and heritage inland waterways open up to us, and the unique perspective they provide. Boating is fun and easy. This pack is designed to help you get afloat if you are thinking about buying a boat. Amongst other useful information, it includes details of: Navigation Authorities British Waterways (BW) and the National Rivers Authority (NRA), which is to become part of the new Environment Agency for England and Wales on 1 April 1996, manage most of our navigable rivers and canals. We are responsible for maintaining the waterways and locks, providing services for boaters and we licence and manage boats. There are more than 20 smaller navigation authorities across the country. We have included information on some of these smaller organisations. Licences and Moorings We tell you everything you need to know from, how to apply for a licence to how to find a permanent mooring or simply a place for «* ^ V.’j provide some useful hints on buying a boat, includi r, ...V; 'r 1 builders, loans, insurance and the Boat Safety Sch:: EKVIRONMENT AGENCY Useful addresses A detailed list of useful organisations and contacts :: : n a t io n a l libra ry'& ■ suggested some books we think will help you get t information service Happy boating! s o u t h e r n r e g i o n Guildbourne House, Chatsworth Road, W orthing, West Sussex BN 11 1LD ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 1 Owning a Boat Buying a Boat With such a vast.range of boats available to suit every price range, . -

Report 207 Cover Bleed.Indd

NumberNumber 207 207 DecemberDecember 2014 2014 THE BOAT MUSEUM SOCIETY President: Di Skilbeck MBE Vice-Presidents: Alan Jones, Harry Arnold MBE, Tony Lewery DIRECTORS Chairman: Jeff Fairweather Vice-Chairman: Will Manning Vice-Chairman: Chris Kay Treasurer: Barbara Kay Barbara Catford Lynn Potts Terry Allen Sue Phillips Bob Thomas Cath Turpin Mike Turpin CO-OPTED COMMITTEE MEMBERS Martyn Kerry 8 Newbury Way, Moreton, Wirral. CH46 1PW Ailsa Rutherford 14 Tai Maes, Mold, Flintshire, CH7 1RW EMAIL CONTACTS Jeff Fairweather [email protected] Barbara Catford [email protected] Ailsa Rutherford [email protected] Lynn Potts [email protected] Andy Wood [Re:Port Editor] 34 Langdale Road, Bebington, CH63 3AW T :0151 334 2209 E: [email protected] The Boat Museum Society is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England Number 1028599. Registered Charity Number 501593 On production of a current BMS membership card, members are entitled to free admission to the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester, and the Stoke Bruerne Canal Museum. Visit our website www.boatmuseumsociety.org.uk The National Waterways Museum, Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, CH65 4FW, Telephone: 0151 355 5017 http://canalrivertrust.org.uk/national-waterways-museum Cover: Bunbury Locks [Photo: © Steve Daniels Creative Commons] Number 207 December 2014 Chairman’s Report The Boat Museum Society (BMS) is the successor of the North Western Museum of Inland Navigation (NWMIN), which was the original body of volunteers who founded and operated the Boat Museum at Ellesmere Port which subsequently became the National Waterways Museum (NWM). The principal aim of the BMS is the preservation of the historic boats, artefacts, skills and knowledge associated with waterway life. -

A Walk from Church Minshull

A Walk to Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina photo courtesy of Bernie Stafford Aqueduct Marina, the starting point for this walk, was opened in February 2009. The marina has 147 berths, a shop and a café set in beautiful Cheshire countryside. With comprehensive facilities for moorers, visiting boaters and anyone needing to do, or have done, any work on their boat, the marina is an excellent starting point for exploring the Cheshire canal system. Starting and finishing at Church Minshull Aqueduct Marina, this walk takes in some of the prettiest local countryside as well as the picturesque village of Church Minshull and the Middlewich Branch of the Shropshire Union Canal. Some alternative routes are also included at the end to add variation to the walk which is about five or six miles, depending on the exact route taken. Built to join the Trent and Mersey Canal with the Chester Canal, the Middlewich Branch carried mainly coal, salt and goods to and from the potteries. Built quite late in the canal building era, like so many other canals, this canal wasn’t as successful as predicted. Today, however, it is a very busy canal providing an essential link between the Trent and Mersey Canal at Middlewich and the Llangollen Canal as well as being part of the Four Counties Ring and linking to the popular Cheshire Ring boating route. The Route Leaving the marina, walk to the end of the drive and turn north (right) onto the B5074 Church Minshull road and walk to the canal bridge. Cross the canal and turn down the steps on the right onto the towpath, then walk back under the bridge, with the canal on your left. -

River Slea Including River Slea (Kyme Eau) South Kyme Sleaford

Cruising Map of the River Slea including River Slea (Kyme Eau) South Kyme Sleaford Route 18M3 Map IssueIssue 117 87 Notes 1. The information is believed to be correct at the time of publication but changes are frequently made on the waterways and you should check before relying on this information. 2. We do not update the maps for short term changes such as winter lock closures for maintenance. 3. The information is provides “as is” and the Information Provider excludes all representations, warranties, obligations, and liabilities in relation to the Information to the maximum extent permitted by law. The Information Provider is not liable for any errors or omissions in the Information and shall not be liable for any loss, injury or damage of any kind caused by its use. SSLEALEA 0011 SSLEALEA 0011 This is the September 2021 edition of the map. See www.waterwayroutes.co.uk/updates for updating to the latest monthly issue at a free or discounted price. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right. All other work © Waterway Routes. Licensed for personal use only. Business licences on request. ! PPrivaterivate AAccessccess YYouou mmayay wwalkalk tthehe cconnectingonnecting ppathath bbyy kkindind ppermissionermission ooff tthehe llandowners.andowners. PPleaselease rrespectespect ttheirheir pprivacy.rivacy. ! BBridgeridge RRiveriver SSlealea RRestorationestoration PProposedroposed ! PPaperaper MMillill BBridgeridge PPaperaper MMillill LLockock oror LeasinghamLeasingham MillMill LockLock 1.50m1.50m (4'11")(4'11") RRiveriver SSlealea -

Annual Report and Accounts 2005-06

CONTACT DETAILS WATERWAYS BRITISH Head Office Customer Service Centre Willow Grange, Church Road, Willow Grange, Church Road, Watford WD17 4QA Watford WD17 4QA T 01923 226422 T 01923 201120 ANNUAL REPORT & F 01923 201400 F 01923 201300 PUBLIC BENEFITS [email protected] FROM HISTORIC WATERWAYS BW Scotland Northern Waterways Southern Waterways British Waterways ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Canal House, Willow Grange ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2005/06 Applecross Street, North West Waterways Central Shires Waterways Church Road Glasgow G4 9SP Waterside House, Waterside Drive, Peel’s Wharf, Lichfield Street, Watford T 0141 332 6936 Wigan WN3 5AZ Fazeley, Tamworth B78 3QZ WD17 4QA F 0141 331 1688 T 01942 405700 T 01827 252000 enquiries.scotland@ F 01942 405710 F 01827 288071 britishwaterways.co.uk enquiries.northwest@ enquiries.centralshires@ T +44 1923 201120 britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk F +44 1923 201300 BW London E [email protected] 1 Sheldon Square, Yorkshire Waterways South West Waterways www.britishwaterways.co.uk Paddington Central, Fearns Wharf, Neptune Street, Harbour House, West Quay, www.waterscape.com, your online guide London W2 6TT Leeds LS9 8PB The Docks, Gloucester GL1 2LG to Britain’s canals, rivers and lakes. T 020 7985 7200 T 0113 281 6800 T 01452 318000 F 020 7985 7201 F 0113 281 6886 F 01452 318076 ISBN 0 903218 28 3 enquiries.london@ enquiries.yorkshire@ enquiries.southwest@ Designed by 55 Design Ltd britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk britishwaterways.co.uk Printed by Taylor -

2020 Jul-Aug

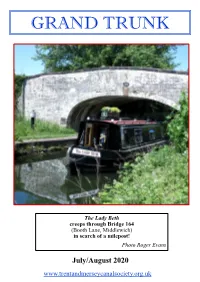

GRAND TRUNK The Lady Beth creeps through Bridge 164 (Booth Lane, Middlewich) in search of a milepost! Photo Roger Evans July/August 2020 www.trentandmerseycanalsociety.org.uk Chairman’s Bit Will July 4th be celebrated as “Independence Day” in England now as well as in the USA??? We have been making a short 1-day cruise each week since they were allowed, but on 4th July we will be heading off for our much-delayed annual “Spring” cruise around the “Four Counties Ring” (and Yes, we have booked Harecastle Tunnel). By the time you read this we will be safely back home plan- ning our next outing (probably the Caldon to see if we fit through Froghall Tunnel). How do I know that we will be safely back home before you read this? Simple, because it is Margaret and I who will be posting it to you … What condition will be find our canal in ? Based on our short local outings, I expect to find the towpath almost invisible from the canal in many places and several bottom lock-gates to be much leakier with locks slower to fill. A couple of weeks of busy boat movements will probably get those gates to swell-up and seal better again, but I suspect that the “invisible” towpaths will take longer to reappear. Never mind, we will enjoy our first week’s cruise regardless and some days we may even forget “Covid-19” still exists. That’s what canal boating is all about. Thank you to the 14 people who returned a Gift-Aid form (physically or on- line) after my appeal in the last issue. -

Four Counties Ring from Stone | UK Canal Boating

UK Canal Boating Telephone : 01395 443545 UK Canal Boating Email : [email protected] Escape with a canal boating holiday! Booking Office : PO Box 57, Budleigh Salterton. Devon. EX9 7ZN. England. Four Counties Ring from Stone Cruise this route from : Stone View the latest version of this pdf Four-Counties-Ring-from-Stone-Cruising-Route.html Cruising Days : 8.00 to 12.00 Cruising Time : 60.00 Total Distance : 110.00 Number of Locks : 93 Number of Tunnels : 2 Number of Aqueducts : 0 From the Shropshire Union Canal through the rolling Cheshire Plains to the Trent & Mersey Canal, the Staffordshire & Worcester Canal and back via the Shropshire Union the Four Counties Ring is one of the more rural Cruising Rings and is best savoured slowly. The four counties that the routes passes through are Cheshire, Staffordshire, Worcestershire and Shropshire. Highlights include the Industrial Canal Heritage of the Stoke-on-Trent potteries region, the wealthy pasturelands of Cheshire, to the stunning remote sandstone cuttings of Shropshire, as well as the Harecastle Tunnel at 2926 yards one of the longest in Britain and reputed to be haunted by a headless corpse whose body was dumped in the Canal. This is an energetic cruise over 7 days, and more leisurely over 10/11 nights Cruising Notes Day 1 The bulk of Stone lies to the east bank. There is a profusion of services and shops in Stone with the High Street being pedestrianized and lying just a short walk from the canal it is very convenient. South of Stone the trees surrounding the canal thin out somewhat opening up views of land that is flatter than a lot that came before it giving far reaching views across endless farmland. -

British Waterways Board General Canal Bye-Laws

BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD GENERAL CANAL BYE-LAWS 1965 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD BYE-LAWS ____________________ for regulation of the canals belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board (other than the canals specified in Bye-law 1) made pursuant to the powers of the British Transport Commission Act, 1954. (N.B. – The sub-headings and marginal notes do not form part of these Bye-laws). Application of Bye-laws Application of 1. These Bye-laws shall apply to every canal or inland navigation in Bye-Laws England and Wales belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board except the following canals: - (a) The Lee and Stort Navigation (b) the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal (c) the River Severn Navigation which are more particularly defined in the Schedule hereto. Provided that where the provisions of any of these Bye-laws are limited by such Bye-law to any particular canal or locality then such Bye-law shall apply only to such canal or locality to which it is so limited. These Bye-laws shall come into operation at the expiration of twenty-eight days after their confirmation by the Minister of Transport as from which date all existing Bye-laws applicable to the canals and inland navigations to which these Bye-laws apply (other than those made under the Explosives Act 1875, and the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act 1928) shall cease to have effect, without prejudice to the validity of anything done thereunder or to any liability incurred in respect of any act or omission before the date of coming into operation of these Bye-laws. -

Message from the Chair

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR At our recent end of season review, we acknowledged 2018 as a year of huge progress for Lyneal Trust with, including the expected Santa Cruise activity, a record of around 1800 people using the Trust’s facilities. This has been achieved by the success of Shropshire Lady’s first full year, Shropshire Maid’s introduction, Shropshire Lass’s refurbishment and improve- ments at Wharf Cottage and The Lyneal Trust’s boats were in use again this grounds. On behalf of all year for the annual Whitchurch Rotary Boat trips. involved with Lyneal Trust, I 24 two-hour trips carried a record 215 passengers including would like to thank the many primary school children, children with a wide range of volunteers, trustees, supporters, neurological and physical disorders and behavioural customers and local community difficulties and residents from care homes. There was much groups who have made a huge positive feedback on the boats, especially The Shropshire contribution this year. Lady. The bright, airy feel and the superb view from a seated position were widely commented on. One child Wishing you all a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. commented "It was the best school trip we've ever had". Costs were covered by 28 local businesses who each Chris Symes (Chair of the sponsored a boat. Rotary are very grateful to them, to the Trust) Whitchurch Waterway's Trust and to Chemistry Farm and of Editor: Gabrielle Pearson course to Lyneal Trust. Sub Editor: Chris Smith Lyneal Trust, Lyneal Wharf, Lyneal, Ellesmere, Shropshire SY12 0LQ. Registered Charity Number 516224 VOLUNTEERS IN ACTION The Lyneal Story (continued) ANGELA BUNCE By 2012, Shropshire Lad was showing its age and a replacement day boat became a priority. -

CHESHIRE OBSERVER 1 August 5 1854 Runcorn POLICE COURT

CHESHIRE OBSERVER 1 August 5 1854 Runcorn POLICE COURT 28TH ULT John Hatton, a boatman, of Winsford, was charged with being drunk and incapable of taking care of himself on the previous night, and was locked up for safety. Discharged with a reprimand. 2 October 7 1854 Runcorn ROBBERY BY A SERVANT Mary Clarke, lately in the service of Mrs Greener, beerhouse keeper, Alcock Street, was, on Wednesday, charged before Philip Whiteway Esq, at the Town Hall, with stealing a small box, containing 15s 6d, the property of her late mistress. The prisoner, on Monday evening, left Mrs Greener's service, and the property in question was missed shortly afterwards. Early on Tuesday morning she was met by Davis, assistant constable, in the company of John Bradshaw, a boatman. She had then only 3 1/2d in her possession, but she subsequently acknowledged that she had taken the box and money, and said she had given the money to a young man. She was committed to trial for the theft, and Bradshaw, the boatman, was committed as a participator in the offence, but was allowed to find bail for his appearance. 3 April 14 1855 Cheshire Assizes BURGLARY William Gaskell, boatman, aged 24, for feloniously breaking into the dwelling house of Thomas Hughes, clerk, on the night of the 8th August last, and stealing therefrom a silver salver and various other articles. Sentenced to 4 years penal servitude. FORGERY Joseph Bennett, boatman, was indicted for forging an acceptance upon a bill of exchange, with intent to defraud Mr Henry Smith, of Stockport, on the 29th of August last; also with uttering it with the same intent. -

Narrowboats Napton

Napton Narrowboats CANAL HOLIDAYS IN ENGLAND AND WALES AN ELITE 4 PASSING THROUGH CROPREDY ON THE OXFORD CANAL Napton Marina Stockton, Southam Warwickshire CV47 8HX Mobile WiFi on Tel: 01926 813644 all boats Internet: www.napton-marina.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] 1 / 17 Napton Narrowboats CRUISING FROM NAPTON MARINA & AUTHERLEY JUNCTION For comprehensive details of cruising routes see our website 2 2 / 17 Excellent instructions that enabled us to feel confident and enjoy our experience. Mr Hartley, Dewsbury PICTURESQUE SCENERY DELIGHTS YOU AROUND EVERY BEND With Napton Narrowboats you can cruise the majority of the English canal system from our bases at Napton on the Oxford Canal or Autherley Junction on the Shropshire Union Canal. You have a wide choice of all the major canal rings and canals, each with their own character and charm. Slow Down... You can slow the pace down a bit and relax from the rat race for a while. Watch the wildlife and enjoy the countryside with long leisurely lunches at a country pub. Journey Through Time... Built over 200 years ago, the canals meander through the countryside, passing near ancient castles, stately homes, historical market towns and cities, and even theme parks. You can stop and visit places like: The Wedgwood Factory, Nantwich, Alton Towers, Banbury, Blenheim Palace or Stratford upon Avon. Bring The Kids... Children love the adventure of a canal holiday. They like to help work the locks and steer the boat (with adult supervision) or pretend they're on a pirate adventure. Needless to say there are always hungry ducks! Napton Narrowboats has been a family run business for 30 Years Do Something New.. -

NCN Route 75 Route 75 Takes in the Cheshire Route from Audlem to Winsford

NCN Route 75 Route 75 takes in the Cheshire route from Audlem to Winsford. Grade National Cycle Network Distance 38km/24mile Time 2-3 hours Start County boundary Nr Audlem Map OS Landranger 118 Terrain Country lanes, public roads, off road tracks Barriers N/A Toilets Public toilets in most towns you pass through Contact www.sustrans.org.uk Route Details Route 75 is unusual as it starts deep in the heart of Shropshire at Market Drayton and links into national Route 5 at Winsford. We will also share part of the route with 70 and 74. Unless you have followed the route from Market Drayton, Audlem may be a suitable starting point. If you want to start at the county boundary though, the road is very narrow with some steep climbs. Before reaching Audlem you may want to check out the famous canal locks between Swanbach and Audlem village. If you do, just divert left at Kinsey Heath and follow this road until you reach the canal. Please push your bikes down past the locks, there are lots of pedestrians and canal users and the path is not that wide. It's also quite steep! Take some time in Audlem it's a beautiful village with a lovely tea shop or two! From Audlem follow the A525 for a short distance. This is an A road though not as busy as some, it still carries some heavy traffic at times. This section is common with the Cheshire Cycleway, Route 70. The landscape is undulating and open and you will head north towards Ravensmoor and Nantwich.