Anticipating Independence, No Premonition of Partition. the Lessons of Bank Branch Expansion on the Indian Subcontinent, 1939 to 1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cra Ratings of Massachusetts Banks, Credit Unions, and Licensed Mortgage Lenders in 2016

CRA RATINGS OF MASSACHUSETTS BANKS, CREDIT UNIONS, AND LICENSED MORTGAGE LENDERS IN 2016 MAHA's Twenty-Sixth Annual Report on How Well Lenders and Regulators Are Meeting Their Obligations Under the Community Reinvestment Act Prepared for the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance 1803 Dorchester Avenue Dorchester MA 02124 mahahome.org by Jim Campen Professor Emeritus of Economics University of Massachusetts/Boston [email protected] January 2017 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF MAJOR FINDINGS Since 1990, state and federal bank regulators have been required to make public their ratings of the performance of individual banks in serving the credit needs of local communities, in accordance with the provisions of the federal Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and its Massachusetts counterpart. And since 1991, the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance (MAHA) has issued annual reports offering a comprehensive listing and analysis of all CRA ratings of Massachusetts banks and credit unions. This is the twenty-sixth report in this annual series. Since 2011 these reports have also included information on the CRA-like ratings of licensed mortgage lenders issued by the state’s Division of Banks in accordance with its CRA for Mortgage Lenders regulation. As defined for this report, there were 153 “Massachusetts banks” as of December 31, 2016. This includes not only 131 banks that have headquarters in the state, but also 22 banks based elsewhere that have one or more branch offices in Massachusetts.1 Table A-1 provides a listing of the 153 Massachusetts -

Banking Awareness Question Bank V2

www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com www.BankExamsToday.com Banking Awareness By Ramandeep Singh Question Bank v2 www.BankExamsToday.com S. NO. Banking AwarenessTOPICS Question Bank v2 PAGE NO. 1. 2. 3. History of Banking 2 - 4 4. Reserve Bank of India 4 - 7 5. NABARD 7 – 10 6. IRDAwww.BankExamsToday.com10 - 12 7. BIS 12 - 15 8. International Organizations 16 - 18 9. National Housing Bank 19 - 21 10. Credit/Debit Cards 21 - 24 11. Fiscal Policy 24 - 27 12. ATM 27 - 30 13. Banking OMBUDSMAN (Part 2) 30 - 33 14. Letter of Credit 33 - 36 15. WTO 36 - 39 16. World Bank 39 - 42 17. Allahabad Bank 42 - 45 18. Syndicate Bank 45 – 48 19. Oriental Bank of Commerce 48 - 51 20. Axis Bank 51 – 54 21. Punjab & Sind Bank 55 – 58 22. Bank of Baroda 58 – 60 23. ICICI Bank 60 – 63 24. PNB 63 – 66 25. United Bank of India 66 – 69 26. Vijaya Bank 69 - 72 27. ICICI Bank 72 – 75 28. Credit/Debit Cards (Part 2) 75 – 78 Canara Bank 78 – 81 Mixed Topics 81 - 121 By Ramandeep Singh Page 2 www.BankExamsToday.com HISTORY OF BANKINGBanking Awareness Question Bank v2 Q1. First Bank established in India was: a) Bank of India b) Bank of Hindustan c) General Bankwww.BankExamsToday.com of India d) None of The Above Q2. Bank of Hindustan was established in ____: a) 1700 b) 1770 c) 1780 d) None of The Above Q3. Which among the following is correct regarding Bank of Hindustan: a) The bank was established at calcutta under European management. -

OCC, Report of the Ombudsman (2005-2006)

Appendix A OCC Formal Enforcement Actions in the Consumer Protection Area 2009: • Florida Capital Bank, N.A., Jacksonville, Florida (formal agreement – March 26, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations. • National Bank of Arkansas, North Little Rock, Arkansas (formal agreement – March 30, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations. • Merchants Bank of California N.A., Carson, California (formal agreement – March 31, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve its information security program and to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations. • Ozark Heritage Bank, N.A., Mountain View, Arkansas (operating agreement – Apr. 10, 2009). We required the bank to adopt and ensure adherence to a written consumer compliance program. • Farmers and Merchants National Bank of Hatton, Hatton, North Dakota (formal agreement – May 11, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations. • Stone County National Bank, Crane, Missouri (formal agreement – June 25, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations and to strengthen internal controls to improve its information security program. • Union National Community Bank, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (formal agreement – Aug. 27, 2009). We required the bank to strengthen internal controls to improve compliance with applicable consumer laws and regulations. 2008: • Crown Bank N.A., Ocean City, New Jersey (consent order – Feb. 19, 2008). We required the bank to pay a civil money penalty of $7,500 for violations of HMDA and its implementing regulation. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

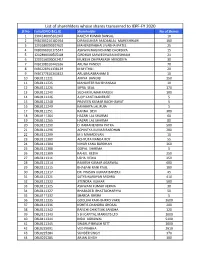

DBL Share Transferred List.Xlsx

List of sharehlders whose shares transerred to IEPF‐FY 2020 Sl No Folio/DPID &CL ID Shareholder No of Shares 1 1304140005162947 RAKESH KUMAR BANSAL 10 2 IN30305210182764 DIPAKKUMAR MADANLAL MAHESHWARI 100 3 1202680000107629 MAHENDRABHAI JIVABHAI PATEL 25 4 IN30066910175547 ASHWIN NAGINCHAND CHORDIYA 15 5 1202890000505108 GIRDHAR SARWESHWAR MESHRAM 21 6 1203150000062419 MUKESH OMPRAKASH NIMODIYA 30 7 IN30198310442636 ARUNA PANDEY 70 8 IN30226911138129 M MYTHILI 20 9 IN30177410343452 ARULRAJABRAHAM D 10 10 DBL0111221 AMIYA BANERJI 250 11 DBL0111225 MAHAVEER RAJ BHANSALI 10 12 DBL0111226 SIPRA SEAL 170 13 DBL0111240 SUDHIR KUMAR PAREEK 100 14 DBL0111246 AJOY KANTI BANERJEE 5 15 DBL0111248 PRAVEEN KUMAR BACHHAWAT 5 16 DBL0111249 KANHAIYA LAL RUIA 5 17 DBL0111251 RANNA DEVI 300 18 DBL0111264 HAZARI LAL SHARMA 60 19 DBL0111265 HAZARI LAL SHARMA 80 20 DBL0111290 D RAMANENDRA PATRA 500 21 DBL0111296 ACHINTYA KUMAR BARDHAN 200 22 DBL0111299 M S MAHADEVAN 10 23 DBL0111300 ACHYUTA NANDA ROY 55 24 DBL0111304 NIHAR KANA BARDHAN 360 25 DBL0111308 GOPAL SHARMA 5 26 DBL0111309 RAHUL KEDIA 250 27 DBL0111311 USHA KEDIA 250 28 DBL0111314 RAMESH KUMAR AGARWAL 600 29 DBL0111315 BHABANI RANI PAUL 100 30 DBL0111317 DR PRASUN KUMAR BANERJI 45 31 DBL0111321 SATYA NARAYAN MISHRA 410 32 DBL0111322 JITENDRA KUMAR 500 33 DBL0111325 ASHWANI KUMAR VERMA 30 34 DBL0111327 BHABADEB BHATTACHARYYA 50 35 DBL0111332 SHARDA KHERA 5 36 DBL0111335 GOOLBAI KAIKHSHRRO VAKIL 3600 37 DBL0111336 KSHITIS CHANDRA GHOSAL 200 38 DBL0111342 RANCHI CHIKITSAK SANGHA 120 39 DBL0111343 S B I CAPITAL MARKETS LTD 1000 40 DBL0111344 INDU AGRAWAL 5400 41 DBL0111345 SWARUP BIKASH SETT 1000 42 DBL0225091 VED PRABHA 2610 43 DBL0225284 SUNDER SINGH 370 44 DBL0225285 ARJAN SINGH 100 45 DBL0225286 SAIN DASS AGGARWAL. -

Customer Attitude on Service Quality of Private Banks in Tiruchirappalli

26326 R.Karthi et al./ Elixir Marketing Mgmt. 73 (2014) 26326-26329 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Marketing Management Elixir Marketing Mgmt. 73 (2014) 26326-26329 Customer Attitude on Service Quality of Private Banks in Tiruchirappalli R.Karthi *, B.Asha Daisy and M.Ganga E.G.S.Pillay Engineering College Nagapattinam, Tamilnadu, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Marketing in today’s world is so difficult for existing players and the new entrants due to Received: 10 June 2014; the fast growing, changes in the customer preference and tastes, rapid growth of Received in revised form: technology, penetration of foreign players in the local market, price sensitiveness of 25 July 2014; customers and quality consciousness of government for attracting, acquiring, retaining Accepted: 9 August 2014; customers in the business. To identify the attitude of the customer in the banking sector, a study has been made in the Tiruchirappalli region among private bank. Keywords © 2014 Elixir All rights reserved. Customer Attitude, Service Quality, Private Banks. Introduction Reserve bank of India (RBI) came in picture in 1935 and Retail banking Industry is growing rapidly in a fast and study became the centre of every other bank taking away all the phase to acquire and retain the customers. To face the global responsibilities and functions of Imperial bank. Between 1969 competition the private banks are taking innumerable steps to and 1980 there was rapid increase in the number of branches of defend their business in order to maximize their potential the private banks. In April 1980, they accounted for nearly 17.5 business. -

Do Bank Mergers, a Panacea for Indian Banking Ailment - an Empirical Study of World’S Experience

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 21, Issue 10. Series. V (October. 2019), PP 01-08 www.iosrjournals.org Do Bank Mergers, A Panacea For Indian Banking Ailment - An Empirical Study Of World’s Experience G.V.L.Narasamamba Corresponding Author: G.V.L.Narasamamba ABSTRACT: In the changed scenario of world, with globalization, the need for strong financial systems in different countries, to compete with their global partners successfully, has become the need of the hour. It’s not an exception for India also. A strong financial system is possible for a country with its strong banking system only. But unfortunately the banking systems of many emerging economies are fragmented in terms of the number and size of institutions, ownership patterns, competitiveness, use of modern technology, and other structural features. Most of the Asian Banks are family owned whereas in Latin America and Central Europe, banks were historically owned by the government. Some commercial banks in emerging economies are at the cutting edge of technology and financial innovation, but many are struggling with management of credit and liquidity risks. Banking crises in many countries have weakened the financial systems. In this context, the natural alternative emerged was to improve the structure and efficiency of the banking industry through consolidation and mergers among other financial sector reforms. In India improvement of operational and distribution efficiency of commercial banks has always been an issue for discussion for the Indian policy makers. Government of India in consultation with RBI has, over the years, appointed several committees to suggest structural changes towards this objective. -

Merger and Acquisitions in the Indian Banking Sector

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 6 2015 ISSN: 2395-7964 SS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH Merger and Acquisitions in the Indian Banking Sector Prof.D. Suryachandra Rao Faculty of Commerce and Management Krishna University Machilipatnam, A.P Dr. M. Venkateswara Rao Principal Kunda College of Technology & Management Vijayawada, A.P., India Abstract The International Banking scenario has shown major changes in the past few years in terms of the Mergers and Acquisitions. Mergers and Acquisition is a useful tool for the growth and expansion in any Industry and the Indian Banking Sector is no exception. It is helpful for the survival of the weak banks by merging into the larger bank. Due to the financial system deregulation, entry of new players and products with advanced technology, globalization of the financial markets, changing customer behaviour, wider services at cheaper rates, shareholder wealth demands etc., have been on rise. This study shows the impact of Mergers and Acquisitions in the Indian Banking sector. For this purpose, a comparison between pre and post merger performance in terms of Operating Profit Margin, Net Profit Margin, Return on Assets, Return on Equity, Earning per Share, Debt Equity Ratio, Dividend Payout Ratio and Market Share Price has been made. In the initial stage, after merging, there may not be a significant improvement due to teething problems but later they may improve upon. Key words: Mergers. Acquisitions, Financial Performance, Ratio, Profitability 76 01.00 Introduction Mergers and Acquisitions is one of the widely used strategies by the banks to strengthen and maintain their position in the market. -

Consolidation in Indian Banking Industry – Need of the Hour

Business Review Volume 3 Issue 2 July-December 2008 Article 8 7-1-2008 Consolidation in Indian banking industry – need of the hour Syed Ahsan Jamil Institute of Productivity and Management, Lucknow, India Bimal Jaiswal University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Namita Nigam Institute of Environment and Management, Lucknow, India Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.iba.edu.pk/businessreview Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. iRepository Citation Jamil, S. A., Jaiswal, B., & Nigam, N. (2008). Consolidation in Indian banking industry – need of the hour. Business Review, 3(2), 1-16. Retrieved from https://ir.iba.edu.pk/businessreview/vol3/iss2/8 This article is brought to you by iRepository for open access under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. For more information, please contact [email protected]. https://ir.iba.edu.pk/businessreview/vol3/iss2/8 Business Review – Volume 3 Number 2 July – December 2008 DISCUSSION Consolidation in Indian Banking Industry- Need of the Hour Syed Ahsan Jamil Institute of Productivity and Management, Lucknow, India Bimal Jaiswal University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Namita Nigam Institute of Environment and Management, Lucknow, India ABSTRACT his study is aimed at trying to unravel the fast and metamorphic changes been Tbrought about within the Indian banking industry. With the government in India clearly specifying that it will liberalize the entry of foreign banks in India by 2009 alarm bells have started ringing for underperforming banks who largely nurtured under government protection and lack of competition. It is now a fight for survival. -

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION at PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK SUPERVISOR SUBMITTED by Dr

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION AT PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK SUPERVISOR SUBMITTED BY Dr. Suhasini Parashar Anuja (Head, Deptt. Of BBA (B&I) Business Administration) 5th Semester Enrollment No: 0051491807 SESSION: 2007 - 2010 MAHARAJA SURAJMAL INSTITUTE (AFFILIATED BY GURU GOBIND SINGH INDRAPRASTHA UNIVERSITY) C-4 JANAK PURI, NEW DELHI-110058. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that project titled ‘Customer satisfaction at PNB ’ is prepared by Anuja is being Submitted for the partial fulfillment of the Master‘s degree in Business Administration Programme at Maharaja Surajmal Institute, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Delhi. He has successfully completed the project under my constant guidance and support. Signature of the Project Guide (Dr, Suhasini Parashar) Anuja BBA 5th sem. PREFACE Summer training is a very important part of an MBA curriculum. It provides an optimistic iconography for ‗Future‘ existence through which students are able to see the real industrial environment which gives an opportunity to relate theory with practice. I undertook two months training programme at Punjab National Bank (Nangloi) and worked on the project ―Customer Satisfaction at PNB ―. This report is the knowledge acquired by me during this period of training. FEATURE OF THIS REPORT: Several features of this report are designed to make it particularly easy for professionals and students to understand the customer‘s perception about the financial products and services offered by the bank. STRUCTURE: An empirical field approach complementing the text is followed EMPIRICAL APPROACH: This report presents highly technical subject matter without complex formulas by using a balance of text and figures. The approximately 20 figures accompanying the text provide a visual and intuitive opportunity for understanding the material. -

Banking – Law & Practice

RELEVANT FOR DECEMBER, 2019 SESSION ONWARDS STUDY MATERIAL PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMME BANKING – LAW & PRACTICE MODULE 3 ELECTIVE PAPER 9.1 i © THE INSTITUTE OF COMPANY SECRETARIES OF INDIA TIMING OF HEADQUARTERS Monday to Friday Office Timings – 9.00 A.M. to 5.30 P.M. Public Dealing Timings Without financial transactions – 9.30 A.M. to 5.00 P.M. With financial transactions – 9.30 A.M. to 4.00 P.M. Phones 011-45341000 Fax 011-24626727 Website www.icsi.edu E-mail [email protected] Laser Typesetting by AArushi Graphics, Prashant Vihar, New Delhi, and Printed at M P Printers/June 2019 ii PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMME BANKING – LAW & PRACTICE In the contemporary perspective, Indian economy is considered as the one of the fastest growing and emerging economies in the world. Contributing to its high growth are many critical sectors including Agriculture, Banking Industry, Capital Market, Money Market, Financial Services and many more. Among all, ‘Banking Sector’ has unarguably been one of the most distinguished sectors of Indian economy. Indeed, the development of any country depends on the economic growth, the country achieves over a period of time. This confirms the very fact that the role of financial sector in shaping fortunes for Indian economy has been even more critical, as India since independence has been equally focussed on other channels of growth too along with resilient industrial sector and the domestic savings in the government instruments. This prompted India to majorly depend on sectors for its dynamic progression. Considering the fact that banking sector plays a significant role in the economic empowerment and global growth of the country, a balanced and vigil regulation on Banking Sector has been always mandated to ensure the transparent run of this sector while avoiding any tantamount of fraud and malpractices injurious to the interest of investors, stakeholders and country as a whole. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoob Rood Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 7*4-3271

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lackingfrom the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a iBrge round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image o f the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a smalt overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding o f the dissertation.