Water of Life Project Kaiwharawhara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report 02126Att

27/01/2002 04/03/2002 Incident Number Date/Time Complaint notification Summary 12818 28/01/2002 14:06:00 Unpleasant odour from nearby abattoir reported from Odour detected during investigation. Not considered Khandallah, Wellington. to be offensive or objectionable . 12820 29/01/2002 10:58:00 Offensive odour from nearby Sewage Treatment Log only. Plant, Seaview, Lower Hutt. 12843 29/01/2002 10:58:00 Sewage odour coming from nearby Wastewater Log only. Treatment Plant, Seaview. 12834 29/01/2002 13:45:00 Discoloration of Tyres Stream, Rangoon Heights, Investigation found sewage discharge had caused Wellington. discoloration. 12835 29/01/2002 14:25:00 Orange coloured discharge on to beach, Houghton Investigation found iron oxide discharged from Bay, Wellington. surface drainage onto the beach. 12862 29/01/2002 15:15:00 Discoloration of Tyres Stream, Rangoon Heights, On investigation sewage discharge had caused Wellington. discoloration. 12853 29/01/2002 18:09:00 Offensive odour from neighbour, Waikanae, Kapiti Log only, as the event had occurred the previous day. Coast. 12836 29/01/2002 18:55:00 Odour from nearby abattoir, Broadmeadows, On investigation no odour detected. Wellington. 12837 29/01/2002 19:30:00 Discoloration of unnamed stream, Whitemans Valley, On investigation discoloration found to be caused by Upper Hutt. vegetation clearance from drainage ditches. 12838 29/01/2002 20:11:00 Odour from nearby abattoir, Broadmeadows, On investigation, no odour detected Wellington. 12839 29/01/2002 20:26:00 Odour from landfill, Porirua. On investigation, no odour detected 12840 29/01/2002 20:26:00 Odour from landfill, Porirua. -

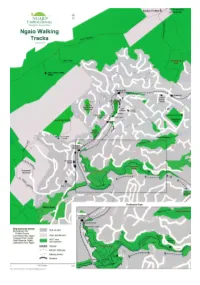

Walking Tracks Running from the Lower Lower the from Running Tracks Walking and Reserves Bush Accessible Many

www.ngaio.org.nz www.metlink.org.nz (Kaukau is a corruption of kaka, the native parrot). native the kaka, of corruption a is (Kaukau Open 1- 4pm Sunday 4pm 1- Open ph 0800 801 700 801 0800 ph and bird snaring was done on the slopes of Mt Kaukau. Kaukau. Mt of slopes the on done was snaring bird and www.teararoa.org.nz 86 Khandallah Road Khandallah 86 Metlink has train and bus timetables and journey planner. journey and timetables bus and train has Metlink in the present Kenya Street - Trelissick Crescent area area Crescent Trelissick - Street Kenya present the in Te Araroa Trail site Trail Araroa Te · · Onslow Historical Society Historical Onslow · to Khandallah. The Kaiwharawhara Pa had gardens gardens had Pa Kaiwharawhara The Khandallah. to Several bus routes connect from Wellington to Ngaio. to Wellington from connect routes bus Several http://wellington.govt.nz route of the present Bridle Track from Winchester Street Street Winchester from Track Bridle present the of route Cummings Park Library, Ngaio Library, Park Cummings · Otari. There was also a track to the north following the the following north the to track a also was There Otari. parks, reserves and heritage trails. trails. heritage and reserves parks, www.tranzmetro.co.nz www.tranzmetro.co.nz www.tracks.org.nz and Makara Pas via various tracks that passed near near passed that tracks various via Pas Makara and and brochures on tracks, walkways, walkways, tracks, on brochures and Downs, Ngaio, Awarua Street, Simla Crescent and Box Hill. Hill. Box and Crescent Simla Street, Awarua Ngaio, Downs, Tracks Tracks · Wellington City Council has maps maps has Council City Wellington · Kaiwharawhara Stream. -

Incident Summary for 08/11/1999 Till 16/01/2000

Attachment 1 to Report 00.41 Page 1 of 15 Incident Summary for 08/11/1999 till 16/01/2000 Complaint Date Time Complaint Details Summary First Response Number (mins) 5047 08/11/1999 Objectionable odour from neighbouring No objectionable odour detected at time of 42 14:00 restaurant, Cuba Mall, Wellington Central. investigation. 5048 09/11/1999 Offensive burning plastic odour. Lyall Bay, No discernible odour detected at the time of 29 08:29 Wellington. investigation. 5050 09/11/1999 Sewage odour possibly coming from the No sewage was present in the Kaiwharawhara 15 09:32 Kaiwharawhara stream, Ngaio Gorge, Stream at the time of investigation. Sewage Wellington. odour in the vacinity of the complainants work premises was sourced to a sewerage interceptor. The local authority was notified of the complaint and are currently taking steps to mitigate the problem. 5068 09/11/1999 Purple paint seen in a side drain, Willis street, Wellington City Council Cityworks notified of 4 12:01 Wellington the complaint. Cityworks to clear up the area. 5056 09/11/1999 Objectionable odour coming from a nearby Under Investigation. No offensive or 30 13:50 restaurant Ghuznee street, Central Wellington objectionable odour detected at the time of investigation 5057 09/11/1999 Welding and plastic odour. Lyall Bay, Logged at complainant's request as officers had 34 15:42 Wellington. already investigated earlier this morning. 5054 09/11/1999 Dead eels in an unnamed stream beside Ruahine Under Investigation 100 17:00 Street, Paraparaumu. 5059 10/11/1999 Sewage odour. Strathmore Park, Wellington. Complainant could not detect any sewage odour 3 18:25 at their property when the officer called. -

Gorge Gazette News About Trelissick Park, the Ngaio Gorge and Streams

Gorge Gazette News about Trelissick Park, the Ngaio Gorge and Streams Abbreviations: WCC Wellington City Council TPG Trelissick Park Group GW Greater Wellington Regional Council DOC Department of Conservation Website www.trelissickpark.org.nz (includes past Gorge Gazettes and Park map) Facebook https://www.facebook.com/TrelissickParkGroup FEBRUARY 2021 An Avian Invasion – Eva Durrant They came in from the north and east forming a flock of over 50 in the centre of Trelissick Park shaking the tree branches into constant movement. This wasn’t a flock of small birds but one of our largest, the kererū. I did not know we had 50 kererū in the area but they put on quite a show recently in one of their annual flocking events. [Eva and Barry Durrant’s house overlooks the lower Kaiwharawhara valley and they delight in witnessing the increasing bird life]. Why? Tawa and karaka trees, probably. They grow everywhere in the lower Kaiwharawhara valley. DOC says that ‘since the extinction of the moa, the kererū and parea are Photo: Bill Hester now the only bird species that are big enough to swallow large fruit, such as those of karaka, miro, tawa and taraire, and disperse the seed over long distances.’ Peter Reimann’s tawa tree above Heke Reserve nearby is laden with more seed than ever seen before. The ice-cream container in the photo, 1/3 full, is only a small sample. They are now planted in a seed tray, optimistically. Good enough to eat? Why Also? The wonderful bird life now in Wellington no doubt mainly comes from the Zealandia ‘halo effect’ and ardent predator control groups throughout the suburbs. -

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This Is Part 1 of a Two Part Trail

Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands. The trail finishes at Ngauranga. Main features of the trail Bridle Track Kaiwharawhara Magazine Crofton Wellington-Manawatu Railway (Johnsonville Line) Wilton House Panels describing the history of the major centres Key Registered as a historic place by the New Zealand Historic Places Trust / Pouhere Taonga Part 1 Listed as a heritage item in the Wellington City District Plan Northern Suburbs Northern Suburbs Heritage Trail Wellington City Around the Kaiwharawhara Basin This is Part 1 of a two part trail. Part 2 is contained in a separate booklet. This part of the trail will take two to three hours to drive. There is some walking involved as well but it is of a generally easy nature. It features the southern suburbs - Kaiwharawhara, Ngaio, Crofton Downs, Wilton and Wadestown - that largely surround and overlook the Kaiwharawhara Stream. Part 2 follows the Old Porirua Road through Ngaio, Khandallah and Johnsonville, Glenside and Tawa with deviations to Ohariu, Grenada Village, Paparangi and Newlands. -

Our 10-Year-Plan Submissions 1124-1372

Our 10‐Year Plan submissions summary 8 to 15 May 2018 ___________________________________________________________________ Submissions 1124 - 1372 No. Name Organisation Page number 1124 Ben 9 1125 Anonymous 12 1126 Anonymous 15 1127 Kayla hunter 18 1128 Steve Whitehouse 21 1129 Anonymous 24 1130 Anonymous 27 1131 Nick Potter 30 1132 Anonymous 33 1133 Ms Leigh Simeona 36 1134 Anonymous 39 1135 Deborah East 42 1136 Anonymous 45 1137 Anonymous 48 1138 Rochelle Emmett 51 1139 Anonymous 54 1140 Sarah Dick 57 1141 Kathy Kemp 60 1142 Hayden 63 1143 Rona 66 1144 Anonymous 69 1145 Andrew Bartlett 72 1146 Joanna Smith 75 1147 Clea Matthews 78 1148 Anonymous 81 1149 Arihia 84 1150 Anonymous 87 1151 Ian Shearer Highland Park Progressive Assn 90 1152 Fiona Roberts 93 1153 Bernadette Ingham 96 1154 Adrian Katz 99 1155 Anonymous 102 1156 Anonymous 105 1157 Christian Williams 108 1158 Anonymous 111 1159 Anonymous 114 1160 Anonymous 117 1161 Anonymous 120 1162 Anonymous 123 1163 Meredith Davis 126 1164 Solinda 129 1165 Anonymous 132 1166 Jack 135 1167 Shane 138 1168 Vaughan Crimmins 141 1169 Anonymous 144 1170 Kris Ericksen 147 1171 Anonymous 150 1172 Anonymous 153 1173 Anonymous 156 1174 Amanda 159 1175 Tom Anderson 162 1176 Adelle Nancekivell 165 1177 Andrew Kensington 168 1178 Laurie‐ann Foon 171 1179 Anonymous 175 1180 Emily 177 1181 Anonymous 180 1182 Anonymous 183 1183 Anonymous 186 1184 Anonymous 189 1185 James Clarke 192 1186 Peter Butson 195 1187 Bronwyn Rendle 198 1188 James Guthrie 201 1189 Carolyn Ann Morgan 204 1190 Tim Kings‐Lynne 207 1191 -

Trelissick Park

1.2 Sector 2 Trelissick Park Trelissick Park is located between the Johnsonville railway line and Ngaio Gorge Road. Most of the park lies on the northern side (true left) of the Kaiwharawhara stream and extends on the eastern side of the Korimako Stream to Crofton Downs. The 20-hectare park forms part of a deep gorge providing a continuous ecological corridor between the harbour and the Outer Green Belt in what is part of the wider Kaiwharawhara catchment. The rounded forms of the upper slopes of the gorge contrast dramatically with the steeper erosion-formed valley sides. Within the park there are a series of quite dramatic bluffs, spurs, steep rock faces and outcrops along with a series of ravine-like side valleys. The park is contiguous with a large area of Railways Corporation land on the true right of the Kaiwharawhara stream. This land has great potential to become part of the ecological corridor but is currently in a degraded state with areas of unstable eroding slopes covered in pest weeds. Trelissick Park is zoned Conservation site under the District Plan and is classified as Scenic Reserve under the Reserves Act 1977. It provides public access from Kaiwharawhara upstream to Waikowhai Street. There are several cross valley links between Wadestown, Ngaio and Crofton Downs. The Northern Walkway between Wellington Botanic Garden and Mt Kaukau and Te Araroa National Walkway also pass through the Park. The valley floor comprises one of Wellington’s largest and most popular off-leash dog exercise areas. The park is closed to mountain bikes under the Open Space Access Plan 2008. -

Strategy 2018-2028

Strategy 2018-2028 He taura whiri kotahi mai anō te kopunga tai no i te pu au From the source to the mouth of the sea all things are joined together as one 1 About this document The Sanctuary to Sea – Kia Mouriora te Kaiwharawhara Strategy 2018-2028 draft has been developed to provide key overarching objectives and a framework for this unique catchment restoration project for the next 10 years. It has been developed by ZEALANDIA in collaboration with the Kaiwharawhara community and key strategic partners. The document is designed to communicate the scope and focus of the Sanctuary to Sea project for community members and strategic partners so that they can both identify how their projects fit with the broader catchment objectives, and to identify new initiatives that can assist the Wellington community in reaching its restoration goals. This strategy will be supported operationally by business planning documents within ZEALANDIA and other strategic partners, and through regular meetings of the Sanctuary to Sea Strategy Group. This strategy sits underneath the ZEALANDIA Te Māra a Tāne Conservation and Restoration Strategy, which highlights the need to look beyond the ZEALANDIA boundary fence to achieve greater things for both nature and people in Wellington and beyond. This project will help achieve multiple ZEALANDIA restoration objectives, including improving fish passage to the sanctuary waterways, and the restoration of the lower lake. The key groups involved in the strategy development include: - ZEALANDIA staff* - Attendees at Sanctuary to Sea community meetings - Greater Wellington Regional Council* - Wellington City Council* - Morphum Environmental Ltd* - Department of Conservation* - Taranaki Whānui* - Wellington Water Ltd* * denotes organisations involved in the Sanctuary to Sea Strategy Group. -

Gorge Gazette News About Trelissick Park, the Ngaio Gorge and Streams (Footbridges Over the Stream Are Numbered from 1 – 6 Going Downstream

Gorge Gazette News about Trelissick Park, the Ngaio Gorge and Streams (Footbridges over the stream are numbered from 1 – 6 going downstream. Abbreviations: WCC Wellington City Council WRA Wadestown Residents’ Association GW Greater Wellington Regional Council VUW Victoria University HPPA Highland Park Progressive Association DOC Department of Conservation TPG Trelissick Park Group F & B Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society NCDRA Ngaio Crofton Downs Residents' Association GG Gorge Gazette Website www.trelissickpark.org.nz (includes past Gorge Gazettes and Park map) Facebook https://www.facebook.com/TrelissickParkGroup MARCH 2018 Matters of Gravity The Park is in a valley, so things fall into it - gravity in action. When 'low-life' humans are involved, this is gravity of the swearing kind. We are forever fishing out rubbish from the Park1. We have pictures of Bill Hester's collections on our Facebook page. WCC kindly remove it from our 'dump' below Trelissick Crescent entrance 3. Kelvin Hastie alerted us to about 15 black plastic rubbish bags chucked down the cliff below Waikowhai Street, near his house. It took three of us nearly two hours to haul these up, using a rope and cradle. In the process, one crashed down to the stream, so we floated it out. Trelissick Crescent is a favourite launch pad. Warrick Fowlie has been scouring the slopes below. Another rope and cradle job. As a novel extension of our 'adopt-a-spot' scheme, Brenton Early adopted all the streams in the Park, to rescue the garbage before it goes out to sea - mostly plastic, we expect. New Inhabitants Peter Reimann was showing new Conservation Volunteers NZ manager Kellie Brenner and her offsider Natalie Jones our problem areas when we spotted a pukeko on railway land near bridge 6. -

Toitū Te Marae a Tāne-Mahuta, Toitū Te Marae a Tangaroa, Toitū Te Tangata

A guide to Restoration Planting Toitū te maraeProtect and strengthen a Tāne the realm of Tāne-Māhuta, god of the forest andRestoration all creatures Planting on land Sites i ISBN number 978-0-947521-18-9 Ihirangi Contents Te whakamahere kaupapa whakatō tipu 5 Ngā rohe kōreporepo wai māori 4 Planning your planting project Freshwater wetlands Ngā tāhuahua, ngā ākau tokatoka 6 Ngā tahataha manga 36 me ngā whīra pātītī Stream sides Sand dunes, rocky shore and turf fields Ngā riu me ngā puketai tuawhenua 41 Ngā tāhuahua 7 Inland basins, valleys and hillsides Sand dunes Ngā kahiwi, ngā pīnakitanga me ngā taumata 48 Ngā tāhuahua me ngā whīra pātītī 10 Ridgelines, upper slopes and hilltops Rocky shore and coastal turf fields Te whakatō tipu whakapaipai ngahere 55 Ngā kūrae me ngā paripari takutai 14 Forest enrichment planting Coastal headlands, cliffs and escarpments Te papa ngahere me ngā momo tipu 58 Ngā puketai me ngā awaawa takutai 18 kei raro iho i te kāuru o te ngahere Coastal hillsides and gullies Forest floor, understorey and sub-canopy species Te ururua mānuka-kānuka 25 Te kāuru o te ngahere me Mānuka-kānuka scrub ngā rākau teitei e tipu tonu ana 61 Canopy and emergent tall trees Ngā wahapū, ngā repo wai tai me ngā rohe 29 kōreporepo wai māori Ngā tipu kaipiki me ngā tipu pipiri 64 Estuaries, saltwater marshes and Climbers and epiphytes freshwater wetlands Kuputaka 66 Ngā nōhanga rohe kōreporepo 30 Glossary Wetland habitats Whakamāoritanga 66 Te whakaora rohe kōreporepo 31 Translation Restoring wetlands He mōhiohio anō 68 Ngā rohe kōrerorepo takutai 32 More information Coastal wetlands Cover tree photo: Tony Stoddard, Kereru Discovery Toitū te marae a Tāne-mahuta, Toitū te marae a Tangaroa, Toitū te tangata. -

The Values and Beliefs Regarding Pet Ownership Around Trelissick Park in Wellington, New Zealand

The Values and Beliefs Regarding Pet Ownership Around Trelissick Park in Wellington, New Zealand Olivia Carson 300306030 Email: [email protected] Abstract With predator-free 2050 on the horizon, urban biodiversity initiatives increase in frequency and so too does the reintroduction of native wildlife into cities across New Zealand. The role that pets, such as cats and dogs, play as predators to these newly introduced natives becomes an issue as human inhabitation and pet ownership grows. The objectives of this study were to investigate the distribution and threat of domestic cats and dogs within an inner-city park and secondly, to survey the community neighbouring this study site regarding their attitudes and beliefs about pet ownership and the threat that domestic cats and dogs pose to native wildlife. Twelve motion-detecting cameras were triggered by cats 30 times during the 30-day study period, and dogs triggered the same cameras 337 times. The online Google forms survey found that the park is highly valued for the role it plays in providing habitat for native wildlife and the open space it provides for the community. Findings show that there is substantial agreement that cats pose a threat to native wildlife. However, this differs for dogs, with more varied results. Education and advocacy on the harmful effects of cats and dogs on native wildlife may alter the behaviour of pet owners who value native biodiversity, but this alone won't be enough to persuade those who appreciate cats and dogs over the proliferation of native fauna. Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge Bill Hester from the Trelissick Park Group for his support and knowledge of the study site, Julian Pilois, Michelle Carson and Curtis Picken for their assistance setting up cameras in the field and helping to distribute flyers. -

Committee Report

Attachment 1 to 03.215 Page 1 of 30 Geoff Skene Manager, Environment Co-ordination Environment Co-ordination Department Report - May 2003 1. Kaiwharawhara Catchment Community Resource Kit (John Holmes) The Community Resource Kit is a joint project of the Wellington City Council and the Greater Wellington Regional Council. It reflects the shared approach that is being taken by the two Councils to managing the Kaiwharawhara Stream. The kit was launched by Councillor Terry McDavitt and WCC Councillor Andy Foster at the Otari-Wilton Bush Information Centre on 12 April. The kit contains information about the stream, its plant and animal life, its geography, and the groups working on its rehabilitation and enhancement. It provides a vision that Greater Wellington, Wellington City Council, the tangata whenua, and others can work towards, and a number of publications and information sheets to guide re-vegetation and management. It contains, for example, an innovative stream pollution “pinwheel” designed by Otari School children while doing the Take Action programme. In many respects, however, the kit is a marker of the point the community and agencies have reached in relation to the Kaiwharawhara stream’s renewal, recording who is working there and what has been achieved. With the Kaiwharawhara set to become one of the first waterways we give greater attention to under the new ten year plan, the kit provides a useful reminder of the contribution that has been made already by Greater Wellington. Some of these initiatives in the last three years