Information 10 Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

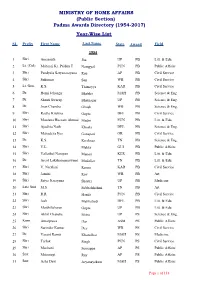

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Analysing Structures of Patriarchy

LESSON 1 ANALYSING STRUCTURES OF PATRIARCHY Patriarchy ----- As A Concept The word patriarchy refers to any form of social power given disproportionately to men. The word patriarchy literally means the rule of the Male or Father. The structure of the patriarchy is always considered the power status of male, authority, control of the male and oppression, domination of the man, suppression, humiliation, sub-ordination and subjugation of the women. Patriarchy originated from Greek word, pater (genitive from patris, showing the root pater- meaning father and arche- meaning rule), is the anthropological term used to define the sociological condition where male members of a society tend to predominates in positions of power, the more likely it is that a male will hold that position. The term patriarchy is also used in systems of ranking male leadership in certain hierarchical churches and ussian orthodox churches. Finally, the term patriarchy is used pejoratively to describe a seemingly immobile and sclerotic political order. The term patriarchy is distinct from patrilineality and patrilocality. Patrilineal defines societies where the derivation of inheritance (financial or otherwise) originates from the father$s line% a society with matrilineal traits such as Judaism, for example, provides, that in order to be considered a Jew, a person must be born of a Jewish mother. Judaism is still considered a patriarchal society. Patrilocal defines a locus of control coming from the father$s geographic/cultural community. Most societies are predominantly patrilineal and patrilocal, but this is not a universal but patriarchal society is characteri)ed by interlocking system of sexual and generational oppression. -

Chapter: 2 Voices of Pioneer Indian Women Memoirists: an Outline

CHAPTER: 2 VOICES OF PIONEER INDIAN WOMEN MEMOIRISTS: AN OUTLINE Who to wed? Who to revere? Couldn’t comprehend the male fear Why to bow? How to conduct? At each corner, obstacles erupt. How to write? When to procreate? What for the world is most appropriate? I ask and get no replies…………………… Moments come, century flies But the quest of female never dies!!!! (Monika Choudhry’s Poem Quest) 2.1 Introduction: Jai Shankar Prassad, the pioneer literary personality of Hindi literature is known for strong portrayals of women. A popular verse from one of his most widely read poems Kamyani (Part: II ‘Lajja’) reads, “नारी! तुम केवल श्र饍धा हो वव�वास-रजत-नग पगतल मᴂ। पीयूष-स्रोत-सी बहा करो जीवन के सुԂदर समतल मᴂ।” Nari! Tum keval shraddha ho, vishwas-rajal-nag-pal-tal mein. Piyush strot si baha karo, Jivan ki sundar samtal mein. [Oh woman! You are honour personified, under the silver mountain of faith flow you, like a river of ambrosia, on this beautiful earth.] The woman is a beautiful creation of God on this beautiful earth. She is a living embodiment of affection, love, compassion, tenderness and so on. In Indian culture and literature, the aesthetic beauty of women represented extraordinarily. Millions of people of the world appreciate Vatsayana’s Kamsutra and Bhartuhari’s Shrungarshatak. Mahakavi Kalidas exceptionally represents the aesthetic beauty of women in his epics. In Meghdoot, the protagonist Yaksha sends messages to his beloved wife by rainy clouds, he narrates aesthetically the beauty of his wife. He appreciates the physical beauty of his wife by these words: तन्वी श्यामा, शिखरिदषणा, प啍वबिम्िोधिोष्टि, मध्यक्षमा, चि啍तहरिनोप्रेक्षना, ननम्ननाभीही, श्रोक्षीभिा, हलसगमाना, स्तोकनमा, स्तनाभया車 etc. -

World Anthology for the Protocol for World Peace

WORLD BIBLIOGRAPHIC INDEX: ALPHABETICAL (I) AND IN ORDER OF ACCESS (II) The collection of texts, from which the materials for the data base of The Protocol for World Peace were abstracted, was begun on January 1, 2000, and the finishing work on the final portion of this effort—the Four Governing Indices (World Table of Contents, World Authors A- Z, World Bibliography, World Archives)—was completed on Christmas Day, 2017. * In this bibliography, every effort has been made to discover for each source its card catalogue identification in the constituent libraries of Cornell University, which appears in each entry as a single-word English short-form of their names—OLIN, ASIA, URIS, AFRICANA, COX, ILR (International Labor Relations) etc.—printed prior to each catalogue number. Very occasionally the source is designated in the RARE collection, referring to the library housed in the Rare Book depository; even more occasionally the source is designated as an “Electronic Resource” (If the source edition actually used is not listed, the nearest English-language edition is listted; if there is no English edition, the closest non-English; if the work is entirely absent, but there is present something else by the author that has been collected, the citation “other stuff” will be seen.) In many cases, these catalogue entries are twinned, and the Cornell reference invariably follows the catalogue entry of the library where the source was originally discovered, thus: [ original citation | Cornell citation ]. * The collection was begun through the auspices of the Interlibrary Loan Department of the Southeast Steuben County Public Library in Corning, New York, and for the first year or so liberal use was made of the various public libraries affiliated in this public library system. -

A Bibliography of Autobiographies

Bibliography of Autobiographies, Memoirs and Reminiscences by Indian authors in English (Unpublished) By Dr. N. Benjamin Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune 411 004 [email protected] People have been writing their own experiences in life since long. But such writings in English in India have been done essentially in the present century. Some of them originally written in the regional languages have also been translated into English. These writings provide an authentic account of all that has been happening around them. They are useful as a source of information for freedom struggle, socio-economic history, business history, functioning of government, etc. They also contain information regarding sports, arts, and so on. The first male-authored autobiography in India was written by the Mughal emperor Babur. Known as Baburnama, it was penned in 1520s. His great grandson, Jahangir, wrote Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri a century later. The third autobiography was written by a non-royal in 1650 - Banarsidas. It was entitled Ardhakatha. Bahina Bai was the first Indian woman to write an autobiography – around in 1700. They have been followed by other writers. Since the subject covered even in a single volume is more than one, they have been listed in an alphabetical order in the following pages. Apart from the autobiographies, memoirs and reminiscences pertaining to their own lives have also been included. Alphabet A: 1. Abbas, Khwaja Ahmad, I am not an island: An experiment in autobiography (New Delhi: Vikas, 1977). 2. Abbasi, Qazi Mohammad Adil, Aspects of politics and society: memoirs of a veteran Congressman (New Delhi, 1981). -

Indian Women: Biographies and Autobiographies

Indian Women: Biographies and Autobiographies (An Annotated Bibliography) Complied by Anju Vyas & Ratna Sharma February 2013 CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES 25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market) New Delhi-110 001 Ph. 91-11-32226930, 322266931 E-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] Website: www.cwds.ac.in/library/library.htm 1 Contents Preface 3-4 List of Libraries (Location Mark) 5 Part-I: Biographies/Autobiographies (Single Entries) 6-42 Indexes 43 Name Index (Personalities) 44-50 Name Index (Authors, Translators…etc) 51-56 Keywords Index 57-62 Geographical Area Index 63-66 Part-II: Biographies/Autobiographies (Multiple Entries) 67-105 Indexes 106 Name Index: (Personalities) 107-108 Name Index (Authors, Translators…etc) 109-118 Keywords Index 119-122 Geographical Area Index 123-125 List of Libraries 126-129 2 Preface A biography/autobiography is a detailed description or account of someone's life. It is defined as “written life of a person”. Biography is a relatively full account of the facts of a person’s life which attempts to set forth his/her character, temperament and milieu, as well as his experiences and activities. Autobiography is a form of biography in which the subject is also the author; it is generally written in the first person and covers most or an important phase of the author’s life. It portrays life in a very aesthetic manner. People in general have a great interest in the lives of great people as well as others, which are notable in some ways. Biography is one of the most popular fields of study providing introduction, inspiration and entertainment. -

Feminism in Modern India the Experience of the Nehru Women (1900-1930)

Feminism in modern India The experience of the Nehru women (1900-1930) Elena Borghi Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 16 October 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Feminism in modern India The experience of the Nehru women (1900-1930) Elena Borghi Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Dirk Moses, European University Institute (Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, European University Institute (Second reader) Prof. Padma Anagol, Cardiff University (External Advisor) Prof. Margrit Pernau, Max Planck Institute for Human Development © Elena Borghi, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author. ABSTRACT The dissertation focuses on a group of women married into the Nehru family who, from the early 1900s, engaged in public social and political work for the cause of their sex, becoming important figures within the north Indian female movement. History has not granted much room to the feminist work they undertook in these decades, preferring to concentrate on their engagement in Gandhian nationalist mobilisations, from the late 1920s. This research instead focuses on the previous years. It investigates, on the one hand, the means Nehru women utilised to enter the public sphere (writing, publishing a Hindi women’s journal, starting local female organisations, joining all-India ones), and the networks within which they situated themselves, on the national and international level. -

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

Reproductive Politics and the Making of Modern India

REPRODUCTIVE POLITICS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN INDIA REPRODUCTIVE POLITICS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN INDIA MYTHELI SREENIVAS university of washington press Seattle Reproductive Politics and the Making of Modern India is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries— and the generous support of The Ohio State University Libraries. Learn more at the TOME website, available at: openmonographs.org. Copyright © 2021 by Mytheli Sreenivas Composed in Minion Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach 25 24 23 22 21 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound in the United States of Amer i ca The digital edition of this book may be downloaded and shared under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 international license (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0). For information about this license, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. This license applies only to content created by the author, not to separately copyrighted material. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact University of Washington Press. university of washington press uwapress . uw . edu In South Asia, print copies of this book are available from Women Unlimited, 7/10, First Floor, Sarvapriya Vihar, New Delhi 110016. library of congress cataloging- in- publication data Names: Sreenivas, Mytheli, author. Title: Reproductive politics and the making of modern India / Mytheli Sreenivas. Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Padma Awards Directory (1954-2007) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Padma Awards Directory (1954-2007) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, May 30, 2007 Page 1 of 124 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt.