Spreading Roots by CORA L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fulham Palace Visitor Leaflet and Site

Welcome to Fulham Palace Pick up our What’s On guide to House and Garden, the find out about upcoming events home of the Bishops of London since AD 704, and We would love /fulhampalacetrust to see your photos! @fulham_palace a longer history stretching @fulhampalace back 6,000 years. Our site includes our historic house Getting here and garden, museum and café; we invite you to explore. Open daily • Free entry Wheelchair and pushchair friendly All ages are welcome to explore our site Drawing Bishop Bishop room café Porteus’s Howley’s library room Bishop Terrick’s p rooms East court Access Ram Chapel Bishop Great hall Sherlock’s room Putney Bridge Putney Exit to Fulham Palace is located on Bishop’s Avenue, just West (Tudor) court o Fulham Palace Road (A219). Visit our website for further information on getting to Fulham Palace including coach access and street parking. West (Tudor) court Museum rooms Accessibility Public areas of Fulham Palace are accessible and Visitor assistance dogs are welcome. Limited accessible parking is available to book. Visit out website for further information. information Shop Fulham Palace Trust Bishop’s Avenue Fulham and site map Main entrance London, SW6 6EA +44 (0)20 7736 3233 Education centre [email protected] Open daily • Free admission * Some rooms may be closed from time Registered charity number 1140088 fulhampalace.org to time for private events and functions Home to a history that never stands still Market barrow Walled garden Buy fresh, organic produce Explore the knot garden, orchard grown in our garden. and bee hives. -

108-114 FULHAM PALACE ROAD Hammersmith, London W6 9PL

CGI of Proposed Development 108-114 FULHAM PALACE ROAD Hammersmith, London W6 9PL West London Development Opportunity 108-114 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 9PL 2 INVESTMENT LOCATION & HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION • Residential led development The site is situated on the west side of Fulham opportunity in the London Borough Palace Road, at the junction of the Fulham Palace Road and Winslow Road, in the London of Hammersmith & Fulham. Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. • 0.09 hectare (0.21 acre). The surrounding area is characterised by a mix of uses; Fulham Palace Road is typified by 3 • Existing, mixed-use building storey buildings with retail at ground floor and comprising retail, office and a mixture of commercial and residential uppers, residential uses. whilst Winslow Road and the surrounding streets predominately comprise 2-3 storey • Proposed new-build development residential terraces. Frank Banfield Park is extending to approximately 3,369 situated directly to the west and Charing Cross Hospital is situated 100m to the south of the sqm (36,250 sq ft) GIA. site. St George’s development known as Fulham • Full planning permission for: Reach is located to the west of Frank Branfield Park with the River Thames beyond. • 32 x private and 2 x intermediate The retail offering on Fulham Palace Road is residential units. largely made up of independent shops, bars and restaurants, whilst a wider range of amenities • 2 x retail units. and retailers is found in central Hammersmith, • 6 basement car parking spaces. located approximately 0.55 km (0.3 miles) to the north of the site. -

The Bishop of London, Colonialism and Transatlantic Slavery

The Bishop of London, colonialism and transatlantic slavery: Research brief for a temporary exhibition, spring 2022 and information to input into permanent displays Introduction Fulham Palace is one of the earliest and most intriguing historic powerhouses situated alongside the Thames and the last one to be fully restored. It dates back to 704AD and for over thirteen centuries was owned by the Bishop of London. The Palace site is of exceptional archaeological interest and has been a scheduled monument since 1976. The buildings are listed as Grade I and II. The 13 acres of botanical gardens, with plant specimens introduced here from all over the world in the late 17th century, are Grade II* listed. Fulham Palace Trust has run the site since 2011. We are restoring it to its former glory so that we can fulfil our vision to engage people of all ages and from all walks of life with the many benefits the Palace and gardens have to offer. Our site-wide interpretation, inspired learning and engagement programmes, and richly-textured exhibitions reveal insights, through the individual stories of the Bishops of London, into over 1,300 years of English history. In 2019 we completed a £3.8m capital project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, to restore and renew the historic house and garden. The Trust opens the Palace and gardens seven days a week free of charge. In 2019/20 we welcomed 340,000 visitors. We manage a museum, café, an award-winning schools programme (engaging over 5,640 pupils annually) and we stage a wide range of cultural events. -

British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777

“So Many Things for His Profit and for His Pleasure”: British and Colonial Naturalists Respond to an Enlightenment Creed, 1727–1777 N MAY OF 1773 the Pennsylvania farmer and naturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) wrote to the son of his old colleague Peter Collinson I(1694–1768), the London-based merchant, botanist, and seed trader who had passed away nearly five years earlier, to communicate his worry over the “extirpation of the native inhabitants” living within American forests.1 Michael Collinson returned Bartram’s letter in July of that same year and was stirred by the “striking and curious” observations made by his deceased father’s friend and trusted natural historian from across the Atlantic. The relative threat to humanity posed by the extinction of species generally remained an unresolved issue in the minds of most eighteenth-century naturalists, but the younger Collinson was evidently troubled by the force of Bartram’s remarks. Your comments “carry Conviction along with them,” he wrote, “and indeed I cannot help thinking but that in the period you mention notwithstanding the amazing Recesses your prodigious Continent affords many of the present Species will become extinct.” Both Bartram and Collinson were anxious about certain changes to the environment engendered by more than a century of vigorous Atlantic trade in the colonies’ indigenous flora and fauna. Collinson 1 The terms botanist and naturalist carry different connotations, but are generally used interchange- ably here. Botanists were essentially those men that used Linnaeus’s classification to characterize plant life. They were part of the growing cadre of professional scientists in the eighteenth century who endeavored to efface irrational forms of natural knowledge, i.e., those grounded in folk traditions rather than empirical data. -

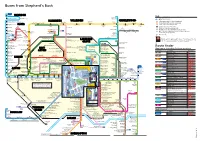

Buses from Sherpherd's Bush

UXBRIDGE HARLESDEN WILLESDEN CRICKLEWOOD HAYES LADBROKE GROVE EAST ACTON EALING ACTON TURNHAM GREEN Buses from Shepherd’s Bush HOUNSLOW BARNES 607 N207 Isleworth Brentford Gunnersbury Uxbridge UXBRIDGE Busch Corner Half Acre 316 Key Uxbridge Civic Centre Uxbridge Park Road Cricklewood 49 Day buses in black Bus Garage WILLESDEN CRICKLEWOOD N207 Night buses in blue HARLESDEN O Connections with London Underground Hillingdon Road The Greenway Harlesden Willesden Cricklewood — Central Middlesex Hospital Jubilee Clock Bus Garage Broadway ChildÕs Hill o Connections with London Overground 260 Hillingdon Lees Road HAYES Craven Park Willesden Cricklewood Golders R Connections with National Rail 228 Harlesden Green Kilburn Green B Connections with river boats South College Park Hayes End M Greenford South Early mornings and evenings only Willesden Junction Brondesbury Perivale Hampstead Chalk Farm G Daytimes only when Wetlands Centre is open Uxbridge 24 hour 31 24 hour 220 service County Court Greenford Park Royal 72 service 283 Swiss Cottage Camden Town L Not served weekday morning and evening peak hours Red Lion Hanger East Acton Lane ASDA Kilburn or Saturday shopping hours ROEHAMPTON Hayes Grapes Industrial Estate Scrubs Lane High Road DormerÕs Mitre Bridge N Limited stop Wells Lane Southall Ruislip Kilburn Park Trinity Road Lady Margaret Park Road s Road Royal Old Oak Common Lane QueenÕs Park The Fairway LADBROKE 95 Scrubs Lane 207 Southall Town Hall North Acton Mitre Way/Wormwood Scrubs 228 Southall Gypsy Corner GROVE Chippenham Road Police -

Office Suite 1 Fulham Palace Bishops Avenue, Fulham, London SW6 6EA Boston Gilmore LLP 020 7603 1616

Office Suite 1 Fulham Palace Bishops Avenue, Fulham, London SW6 6EA Boston Gilmore LLP www.bostongilmore.com 020 7603 1616 Private redecorated office suite Mainly first floor c.1,872 sq ft (174 sq m) approx HOUSE AND GARDEN BACKGROUND The historic house and garden of the Bishop of London since 704, now open to all to discover over 1300 years of British history in the heart of London. For centuries, this Grade I Listed building situated in extensive grounds by the River Thames was the country residence of the Bishops of London. Visitors to Fulham Palace have a wealth of things to see and do from exploring the museum that charts the Palace’s eventful history to having lunch in the Drawing Room restaurant that looks out onto the beautiful gardens. Fulham Palace garden is protected as an important historic landscape. Once enclosed by the longest moat in England, 13 acres remain of the original 36. The surviving layout is mainly 19th century with an earlier Walled Garden and some 18th century landscaping. www.fulhampalace.org LOCATION Fulham Palace and its grounds enjoy a stunning setting alongside Bishops Park on the banks of the River Thames. Bishops Avenue provides vehicular access, which leads to Fulham Palace Road, close to the junction with Fulham High Street and New Kings Road. Alternatively, an attractive riverside walk runs through Bishops Park to Putney Bridge. Putney Bridge Underground Station (District Line) is easily accessible and there are a number of bus routes from Hammersmith and Fulham Broadway. Fulham Palace Road provides convenient access north to Hammersmith Broadway connecting to the M4, and south over the river connecting to the A3/M3. -

“Jogging Along with and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia”

1 Friday, 19 September 2014, 1:30–3:00 p.m.: Panel II: “Leaves” “Jogging Along With and Without James Logan: Early Plant Science in Philadelphia” Joel T. Fry, Bartram's Garden Presented at the ― James Logan and the Networks of Atlantic Culture and Politics, 1699-1751 conference Philadelphia, PA, 18-20 September 2014 Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author These days, John Bartram (1699-1777) and James Logan (1674-1751) are routinely recognized as significant figures in early American science, and particularly botanic science, even if exactly what they accomplished is not so well known. Logan has been described by Brooke Hindle as “undoubtedly the most distinguished scientist in the area” and “It was in botany that James Logan made his greatest contribution to science.” 1 Raymond Stearns echoed, “Logan’s greatest contribution to science was in botany.”2 John Bartram has been repeatedly crowned as the “greatest natural botanist in the world” by Linnaeus no less, since the early 19th century, although tracing the source for that quote and claim can prove difficult.3 Certainly Logan was a great thinker and scholar, along with his significant political and social career in early Pennsylvania. Was Logan a significant botanist—maybe not? John Bartram too may not have been “the greatest natural botanist in the world,” but he was very definitely a unique genius in his own right, and almost certainly by 1750 Bartram was the best informed scientist in the Anglo-American world on the plants of eastern North America. There was a short period of active scientific collaboration in botany between Bartram and Logan, which lasted at most through the years 1736 to 1738. -

Apple Day Festival

Apple day festival Sunday 4 October • 11.00 - 15.00 Please recycle me 1 Crisp Walk, London W6 9DN 020 8237 1020 [email protected] | samsriverside.co.uk Welcome and precautions Welcome to apple day! We have put a number of precautions in place today to follow government guidance on events in light of coronavirus. We ask that you help us by following the measures below, and any guidance given by a member of the Palace team. Please stick to the ‘rule of 6’ when you are on site. Our staff including security team will be checking group sizes and will ask anyone in a group of more than six to leave the site. We will be capping numbers coming onto the site and in the walled garden, so please be patient if you are asked to wait. We ask that if RESTAURANT & BAR you have a picnic please enjoy it on the main lawn or in another area of the botanic garden rather than the walled garden. You will find sanitising stations around the Palace as well as sanitiser on stalls; we ask that you sanitise your hands regularly, patricularly after touching your face, eating and using the facilities. Please follow the 1 metre + rules, keeping a distance from other PROVISIONS & OUTSIDE CATERING visitors and staff, including when you’re queuing. If possible, please pay using card or contactless on the stalls in the garden. Our band will be playing throughout the day, please keep a distance from them and from others listening to them. If you have any concerns or questions please speak to a team member who will be happy to help. -

New Electoral Arrangements for Hammersmith & Fulham Council

New electoral arrangements for Hammersmith & Fulham Council Final Recommendations June 2020 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2020 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Hammersmith & Fulham? 2 Our proposals for Hammersmith & Fulham 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 -

Buses Fom Brook Green, Hammersmith

Buses from Brook Green, Hammersmith Harlesden Cumberland 220 Jubilee Clock Business Park 295 Willesden Junction College Park Scrubs Lane Wormwood Scrubs Ladbroke Grove Sainsbury’s 72 Hammersmith Hospital 283 Ladbroke Grove LADBROKE GROVE Du Cane Road Wood Lane Eagle North Pole Road East Acton East Acton Cambridge Gardens Brunel Road Du Cane Road Du Cane Road Bramley Road EAST ACTON Wood Lane Wood Lane Latimer Road Du Cane Road Bloemfontein Road Wood Lane St. Ann's Road Janet Adegoke Leisure Centre South Africa Road Westway Stoneleigh Place South Africa Road White City Bryony Road Queens Park Rangers F.C. St. Ann's Road BBC TV Centre Wilsham Street Wormholt Road Wood Lane Ariel Way St. Ann's Villas Queensdale Road Uxbridge Road Uxbridge Road Shepherd’s Bush Wood Lane Galloway Road Bloemfontein Road Hammersmith & City Line Uxbridge Road Shepherd’s Bush Central Line Uxbridge Road Uxbridge Road Adelaide Grove Loftus Road Shepherd’s Bush Green SHEPHERD’S BUSH Shepherd’s Bush Road Goldhawk Road The yellow tinted area includes every bus stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from Brook Green, Hammersmith. Main AD stops are shown in the white area outside. OD RO CROMWELL GROVE O D RW E D H A T O NE E R MELROSE GARDENS SID KE LA AD O BLYTHE ROAD R BATOUM G A ARDENS H S U B S ’ DEWHUR School D ST R ROAD E ENA GAR H L DENS P E H STE S RN WS DALE E ROAD M B R C A B R B S OAD R ’ O H OK G D S R R U EE E B N B H P BRO E OK H GR S EEN Shepherd’s Bush Road HAMMERSMITH Hammersmith Library Hammersmith Bus Station Hammersmith Bridge Road Hammersmith Broadway -

Download Our Schools Brochure Here

THAMES EXPLORER TRUST Using the River2020 Thames as an outdoor classroom 2019/20 River Education Programmes www.thames-explorer.org.uk 020 8742 00571 Explore the Thames For details of all our school programmes including the latest news visit our website www.thames-explorer.org.uk We are a charity that raises awareness We provide of the river through a range of • A range of programmes from educational activities. KS1to KS5. For 30 years we have been using the • Activities that support the National River Thames as a valuable, outdoor Curriculum programmes of study in learning tool. Not only are the River science, geography, citizenship, Thames and its tributaries a major history and creative arts. wildlife corridor, but their banks are • Programmes which address the steeped in history making it ideal for National Curriculum objectives in studying a range of subjects. Thousands English and Maths. of people investigated the Thames with • SEND programmes. us last year and took part in one of our • Programmes for pupils not in programmes. mainstream education. • Outreach programmes. • Fieldwork throughout the year led Our programmes by experienced staff. Our programmes are either full or half • Learning resources. day. Full day programmes involve both • Advice on planning a river visit classroom and outdoor work and including pre-site visits. usually take place from 10am to 2.30pm • Inset training. (we can be flexible if the tides allow). Half day courses are 2 hours of field- work with start and finish times being tide dependent. Our programmes take place at different key sites of interest along the tidal Thames where the foreshore is selected to best suit the subject. -

Buses from Harlesden Town Centre

Buses from Harlesden town centre 487 South Harrow N18 continues to Harrow, Wealdstone and Harrow Weald Wembley Park 206 The Paddocks 226 18 The yellow tinted area includes every Golders Green 260 Northolt Park Sudbury & Brent Town Hall Station Parade Harrow Road bus stop up to one-and-a-half miles from Key 266 The Vale Wembley Park Engineers Way Harlesden town centre. Main stops are Olympic Way shown in the white area outside. Brent Cross Shopping Centre Ø— Connections with London Underground Bridgewater Road Whitton Avenue East Great Greenford Road for Sudbury Town Pennine ChildÕs Hill u Connections with London Overground SUDBURY Central Way Brent Park Staples Corner Drive Finchley Road WEMBLEY Hannah Close Tesco BRENT R Connections with National Rail Wembley Central Brent Park PARK Cricklewood Sudbury Town Bus Garage Whitton Avenue East IKEA Anson Road Cricklewood Brentfield Road Burnley Road Hamilton Road The Gladstone Harrow Road Kingfisher Way Aberdeen Road Geary Road Centre Tring Avenue Dollis Hill Kendal Road Anson Road Cricklewood A Brentfield Road Broadway Bridgewater Road Swaminarayan Temple Dudden Hill Lane Cullingworth Road Henson Avenue Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus Harrow Road Chapter Road Flamsted Avenue CHURCH service. The disc !A appears on the top of the bus stop in the Brentfield Road CRICKLEWOOD 1 2 3 Stonebridge Park Gloucester Close END Willesden Dudden Hill Lane Chichele Road 4 5 6 street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). High Road Meyrick Road Willesden High Road Walm Lane