The Arcane World of Cartridge Designations Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firearm Evidence

INDIANAPOLIS-MARION COUNTY FORENSIC SERVICES AGENCY Doctor Dennis J. Nicholas Institute of Forensic Science 40 SOUTH ALABAMA STREET INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46204 PHONE (317) 327-3670 FAX (317) 327-3607 EVIDENCE SUBMISSION GUIDELINE FIREARMS EVIDENCE INTRODUCTION Generally, crimes of violence involve the use of a firearm. The value of firearms and fired ammunition evidence will depend, to a significant degree on the recovery and submission techniques employed at the shooting event or later during autopsy. Trace evidence adhering to surfaces should be collected and submitted to the appropriate agency. This submission guideline is designed to assist you in your laboratory examination request decisions. Any situation not sufficiently explained to your specific needs may be handled on an individual basis by contacting the laboratory at (317) 327-3670 or the Firearms Section Supervisor at (317) 327-3777. A. The following is a list of items most commonly submitted to the Firearms Section for analyses: 1. Firearms 2. Cartridge Cases 3. Cartridges 4. Fired Bullets / Fragments 5. Shotshells 6. Wads 7. Slug / Pellets 8. Victim’s Clothing B. The I-MCFSA Firearms Section can conduct the following analysis: 1. Examination of firearms for function and safety, including test firing in order to obtain test bullets, cartridge cases and shot shells. 2. Comparison of evidence bullets, fired cartridge cases and shot shells to determine if they were or were not fired by the same firearm or the submitted firearm. 3. Examination of fired bullets to potentially determine caliber and possible make and type of firearm involved. 4. Imaging and comparing fired cartridge cases and test shots from firearms to similar exhibits recovered in unsolved crimes utilizing the NIBIN system (see NIBIN Submission Guideline #14). -

Saturday, April 18, 2020

– Large, Grey Eagle/St. Rosa, MN Area – Collectible Tractors and 84 Firearms and Firearms, Collectible Tractors & Equipment Equipment Accessories Sell at 12:00 Noon Lifetime As we are transitioning into retirement, we will sell the following at auction located Collection Collectibles, Shop 1¼ miles north of St. Rosa, MN on County #17 & 35; or being 4 miles north of Melrose, MN on County 13, then 4 miles Equipment, Tools and east on County 17, then ¼ mile north on County 35; or being 1.75 miles south of Grey Eagle, MN on County 33 to the Rock Tavern, Miscellaneous then 4 miles south on County 47 & 35 to home #43311. Follow the Mid-American Auction Co. signs; roads will be plainly marked. Gas Engines, Antique Collectible Tractors & Collectible Items & Farm Equipment 2020 Nice Copper Clad Gas/ Farmall Super Saturday, April 18, Wood Combination C, PTO, Good Kitchen Range, One Metal, Auxiliary Sale Time: 10:30 A.M. Boser’s Lunch Wagon Owner Hydraulics, Sells with Woods 6-Ft. NOTE: The Voits have lived in this area for many years and are well known throughout the community. Don has enjoyed using and Mid-Mount Finishing collecting firearms as well as being an avid hunter and outdoorsman since he was a small boy. Don is also known as a fabricator making Mower, Tractor countless attachments to existing equipment as well as manufacturing many unique new items for customers, friends and neighbors Ser. #122435 1944 John Deere Hand-Crank Styled Model throughout Central Minnesota. After seeing his shop and expertise in many fields, I don’t think there is anything he couldn’t repair Model D Kohler B Tractor, PTO, Cultivator Lift, Good Metal, or make better. -

![219 Zipper [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5970/219-zipper-pdf-425970.webp)

219 Zipper [PDF]

219 ZIPPER .365 12° .253 .506 .422 .252 .063 1.359 1.621 1.938 219 ZIPPER RIFLE: . F.N. Mauser Custom BULLET DIAMETER:. 0.224" BARREL: . 27", 1 in 14" Twist MAXIMUM C.O.L.: . 2.260" CASE: . Remington MAX. CASE LENGTH: . 1.938" PRIMER: . Federal 210 CASE TRIM LENGTH: . 1.928" Winchester introduced the 219 Zipper in 1937, seven years after the Hornet and two years after the powerful 220 Swift. Chambered in the fi rm’s Model 64 lever action varmint version of the famous Model 94, it never delivered the tack-driving accuracy customers demanded and consequently never became widely popular. Winchester discontinued manufacturing the Model 64 after WW II and the 219 Zipper became an orphan in 1961 when Marlin stopped chambering its Model 336 for the cartridge. The Zipper is now completely a handloading proposition since both Remington and Winchester have discontinued producing ammunition. A necked down 25-35 WCF (which can also be formed from 30-30 brass), the 219 Zipper was and is a respectable performer. Top velocities possible for the cartridge are only 100 fps lower than those which can be developed in the 224 Weatherby Varmintmaster. The Hornady 53 grain V-MAX™ or the 55 grain Spire Point are fi ne choices for the 219 Zipper and the cartridge is large enough to propel the wind-bucking 60 grain SP or HP up to an impressive 3300 fps. H 4895 is a very good powder throughout the entire range of available bullet weights and especially with the heavier selections. Hornady 22 caliber V-MAX™ bullets are extra potent in the Zipper. -

Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (Part 1)

NONFERROUSNONFERROUS HEATHEAT TREATING TREATING Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (part 1) Daniel H. Herring – The HERRING GROUP, Inc.; Elmhurst, Ill. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute Inc., also known as SAAMI, is an association of the nation’s leading manufacturers of rearms, ammunition and components. SAAMI is the American National Standards Institute-accredited standards Fig. 1. Firing-pin indent copper crushers developer for the commercial small arms and ammunition industry. SAAMI was for 22-caliber rimfire ammunition founded in 1926 at the request of the federal government and tasked with: creating and (courtesy of Cox Manufacturing and publishing industry standards for safety, interchangeability, reliability and quality; and Kirby & Associates) coordinating technical data to promote safe and responsible rearms use. he story of SAAMI’s rimfire firing-pin indent copper pressures and increased bullet velocities. crusher describes the reinvention of one of the most The primary advantage of rimfire ammunition is low cost, important tools in the ammunition and firearms industry typically one-fourth that of center fire. It is less expensive to T(Fig. 1). This article explains the purpose and operation manufacture a thin-walled casing with an integral-rimmed of the rimfire firing-pin indent copper crusher and how an primer than it is to seat a separate primer in the center of the unusual chain of events almost led to the disappearance of this head of the casing. simple but important technology. The most common rimfire ammunition is the 22LR (22-caliber long rif le). It is considered the most popular round Rimfire Ammunition in the world and is commonly used for target shooting, small- In order to discuss the rimfire copper crusher, we need to take a game hunting, competitive rifle shooting and, to a lesser extent, step back and first explain what rimfire ammunition is and how it works. -

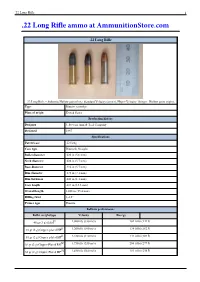

22 Long Rifle Ammo at Ammunitionstore.Com

.22 Long Rifle 1 .22 Long Rifle ammo at AmmunitionStore.com .22 Long Rifle .22 Long Rifle – Subsonic Hollow point (left). Standard Velocity (center), Hyper-Velocity "Stinger" Hollow point (right). Type Rimfire cartridge Place of origin United States Production history Designer J. Stevens Arm & Tool Company Designed 1887 Specifications Parent case .22 Long Case type Rimmed, Straight Bullet diameter .222 in (5.6 mm) Neck diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Base diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Rim diameter .278 in (7.1 mm) Rim thickness .043 in (1.1 mm) Case length .613 in (15.6 mm) Overall length 1.000 in (25.4 mm) Rifling twist 1–16" Primer type Rimfire Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy [] 40 gr (3 g) Solid 1,080 ft/s (330 m/s) 104 ft·lbf (141 J) [] 38 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,260 ft/s (380 m/s) 134 ft·lbf (182 J) [] 31 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) 141 ft·lbf (191 J) [1] 30 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated RN 1,750 ft/s (530 m/s) 204 ft·lbf (277 J) [1] 32 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated HP 1,640 ft/s (500 m/s) 191 ft·lbf (259 J) .22 Long Rifle 2 [][1] Source(s): The .22 Long Rifle rimfire (5.6×15R – metric designation) cartridge is a long established variety of ammunition, and in terms of units sold is still by far the most common in the world today. The cartridge is often referred to simply as .22 LR ("twenty-two-/ˈɛl/-/ˈɑr/") and various rifles, pistols, revolvers, and even some smoothbore shotguns have been manufactured in this caliber. -

Cartridges, Rimfire

SAFETY DATA SHEETPage 1 of 4 Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI, Canadian WHMIS, Australian WorkSafe, Japanese Standard JIS Z 7250:2000, and EU REACH Regulations 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Name: CARTRIDGES – RIMFIRE CAS Number: Mixture – Metal Alloy Synonyms: Rimfire Brands: Super-X, Supreme, Varmint HV, Varmint HE, Defender, USA Brand, Hyper Speed, Dynapoint, M22, 222,333, 525, 555, T-22, Wildcat, Expediter, Silhouette, Super Speed, Aussie Ammo, Subsonic, Power-Point, Xpert, M-22 Subsonic, Super-X Subsonic, Super Suppressed, Varmit X Lead- Free, Varmint LF Polymer Tip NTX, X22LRHLF-22LR Tin 26 grn.HP, X22Mhlf-22WMR Tin Core JHP, USA Game & Target, Universal. Rimfire Bullet Names: Polymer Tip, VMax, XTP, Jacketed Hollow Point, JHP, FMJ, Dynapoint, DP, Lead Round Nose, LRN, LRN Copper Plated, LRN Black Copper Plated, LRN Lubaloy Plated, Lead Hollow Point, LHP, LHP Copper Plated, Power-Point, PP, PP Copper Plated, Fragmenting Hollow Point, FHP, FHP Copper Plated, Lead Shot, CB, T-22. Rimfire Calibers: 17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (17 HMR), 17 Winchester Super Magnum (17 WSM), 22 Long (22L), 22 Long Rifle (22LR), 22 Short (22S), 22 Winchester Rimfire (22WRF), 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (22WMR), 22 Mag. Rimfire Proof Loads Product Use: Rimfire Rifle and Pistol Loaded Ammunition U.N. Number: UN 0012 U.N. Dangerous Goods Explosive, 1.4S Class Manufacturer/Responsible Olin Winchester, LLC Party: Manufacturers’ Address: 600 Powder Mill Road, East Alton, IL 62024 www.winchester.com Emergency Telephone US/Canada: 1-800-424-9300 Number: Outside US/Canada: 703-527-3887 SDS Control Group: 618-258-3507 (Technical Information Only) Olin SDS No.: 00051.0001 Issue Date: 6/1/15 Revision Date: 02/28/2019 Revision No.: 5 2. -

Firearms Evidence Collection Procedures

FIREARMS EVIDENCE COLLECTION PROCEDURES INTRODUCTION: Firearms evidence is usually encountered in crimes against persons such as homicide, assault and robbery; but may also be found in other crimes such as burglary, rape, and narcotics violations. While comparisons of bullets and cartridge cases to specific firearms are the most common examinations requested, other examinations are possible such as: distance determinations based on powder residue or shot spread; examination of firearms for functioning or modification; sequence of shots fired and trajectories; list of possible weapons used; serial number restoration and ownership tracing. Evidence of firing or handling a firearm may be detected through the analysis of gunshot residue collected from a persons hands or other body surfaces. (see PEB 15 12/90). EVIDENCE FIREARMS-HANDLING AND SAFETY: The location and condition of firearms and related evidence at a crime scene should be diagramed and photographed before recovering and securing. Although physical evidence is important, safety must be the first consideration. Each situation should be evaluated before deciding to unload an evidence firearm. (Caution, treat a firearm at all times as if it were loaded). If the weapon is a type that can be safely transported in a loaded condition, this can be done. However, depending on the circumstances it may be unnecessary or unwise to transport a loaded firearm. It should then be unloaded, with care taken to preserve all types of possible evidence. This evidence includes fingerprints, blood, hair or fibers, cylinder "halos", and debris in the barrel and/or cylinder. The weapon should be handled on those areas least likely to retain latent fingerprints such as knurled or checkered areas. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,695.260 B2 Kramer (45) Date of Patent: Apr

USOO8695260B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,695.260 B2 Kramer (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 15, 2014 (54) CARTRIDGES AND MODIFICATIONS FOR 3,898.933 A 8, 1975 Castera et al. M16/AR15 RFLE 4,057,003 A * 1 1/1977 Atchisson ....................... 89,138 4,440,062 A * 4, 1984 McQueen ....................... 89/128 5,033,386 A 7/1991 Vatsvog (76) Inventor: Lawrence S. Kramer, Mount 5,351,598 A * 10/1994 Schuetz .......................... 89.185 Charleston, NV (US) 5,463,959 A 1 1/1995 Kramer 5.499,569 A 3, 1996 Schuetz (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,520,019 A 5/1996 Schuetz patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,987,797 A 1 1/1999 Dustin U.S.C. 154(b) by 120 days 6,293,203 B1 9/2001 Alexander et al. M YW- y yS. 6,609,319 B1 8/2003 Olson 21) Appl. N 12A867,366 6,625,916 B1* 9/2003 Dionne ............................. 42/16 (21) Appl. No.: 9 (Continued) (22) PCT Filed: Feb. 13, 2009 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2O09/034096 Chastain, R. “Hornady's New Ammo Loadings for 2007. A Mixture S371 (c)(1), of New and Old Cartridges' about.com: hunting and shooting Apr. 5, (2), (4) Date: Aug. 12, 2010 2007 online, retrieved on Oct. 14, 2009. Retrieved from the Internet <URL:http://hunting...about.com/od/ammo?a (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2009/137132 newhdyammo2007.htm>. PCT Pub. Date: Nov. 12, 2009 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data US 2011 FOOO5383 A1 Jan. -

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law April 2016 Contents 1. An overview – frequently asked questions on firearms licensing .......................................... 3 2. Definition and classification of firearms and ammunition ...................................................... 6 3. Prohibited weapons and ammunition .................................................................................. 17 4. Expanding ammunition ........................................................................................................ 27 5. Restrictions on the possession, handling and distribution of firearms and ammunition .... 29 6. Exemptions from the requirement to hold a certificate ....................................................... 36 7. Young persons ..................................................................................................................... 47 8. Antique firearms ................................................................................................................... 53 9. Historic handguns ................................................................................................................ 56 10. Firearm certificate procedure ............................................................................................... 69 11. Shotgun certificate procedure ............................................................................................. 84 12. Assessing suitability ............................................................................................................ -

338 Lapua Magnum Brass Comparative Assessments Copyright 2017 Illinois Reloading Lab Accuracy Escalates with the Refinem

338 Lapua Magnum Brass Comparative Assessments Copyright 2017 Illinois Reloading Lab Accuracy escalates with the refinement of CNC Machining and the extreme tolerances we see in today’s rifle actions, barrels and stocks resulting in tight little groups where it matters most - at the target. Last month we released our 6.5 Creedmoor report - and the groups from the range session were simply astounding! This month we release our next report on the “Big Daddy” of true long range rifle calibers, the 338 Lapua Magnum. The term “Long Range” is relative and means something different to each rifleman. I suspect this is due to the distance at which they hunt and practice. For example, if your local rifle range has a 100 yard maximum and you’re hunting the deep thick woods of the east coast, 300 yards might be your definition of long range. But the desert southwest rifleman who has access to a 1000 yard range and can hunt deer well beyond 400 yards, 1000 yards may be long range to them. For this review, let’s agree to the following: Short Range is 0-600 yards, Medium Range is 600- 1000 yards and true Long Range is 1000 yards and beyond. And when I refer to the 338 Lapua in this report – I mean 338 Lapua Magnum Most rifles in the magnum class (300 Win Mag, 7mm Rem Mag, etc.) are designed to provide the velocity needed to reach out beyond 1000 yards and reliably impact targets with enough energy to perform the desired task. The 338 Lapua is in many ways and extension of the “Long Range” tool set, only this time it’s designed to live and perform at ranges few cartridges are even capable of: one mile and beyond. -

Introduction to 9Mm Luger Cartridges

Introduction to Collecting the 9mm Parabellum (Luger) Cartridge Lewis Curtis [email protected] In the November 1958 American Rifleman, Charles Yust had a three page article on the 9mm Parabellum cartridge which illustrated 27 headstamps and listed 110 headstamp codes, many of which never appeared on a 9mm Parabellum cartridge. I was fascinated by the variety of headstamps and loads and began accu- mulating 9mm Para cartridges at the tender age of 17, and have documented over 9000 different variations. Nobody, to my knowledge has a collection approaching 9000 9mm cartridges. A very good collection that doesn’t include date variations would be about 1000 specimens, and a truly outstanding collection would number over 2500. Note that there are over 1500 different headstamps documented. If a collection includes dates, then it could be expected to be two or three times this size. Origin of the 9mm Parabellum Cartridge The 9mm Parabellum cartridge was originally developed by George Luger, at the German company D W M (DWM). In early 1902, George Luger, through the Vickers Limited offered a 9mm version of his pistol to the Small Arms Committee. In mid-1903, three Luger prototype pistols in 9mm were delivered to the US Army for testing at Springfield Arsenal. These are the first pistols known to be chambered for the 9mm Parabellum cartridge. An additional 50 pistols in 9mm, along with 25,000 rounds of ammunition, were provided the US Army for testing in April 1904. The first evidence of German military interest in a 9mm version of the Luger was in March 1904. -

ATF Guidebook - Importation & Verification of Firearms, Ammunition, and Implements of War

U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives ATF Guidebook - Importation & Verification of Firearms, Ammunition, and Implements of War Contents 2 • • This publication was prepared by the Firearms and Explosives Imports Branch (FEIB), Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) to assist Importers and other Firearms Industry Members in identifying firearms, ammunition, and defense articles that may be imported into the United States and to further clarify and facilitate the import process. The FEIB Guidebook was developed to provide guidance in the importation process through the proper recognition and correct use of required forms, regulatory policies, and prescribed import procedures. This guide presents a comprehensive overview of the importation process and provides both relevant and definitive explanations of procedural functions by outlining the existing imports controls including the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), the National Firearms Act (NFA) and the Gun Control Act (GCA). If there are any additional questions or further information is needed, please contact the Firearms and Explosives Imports Branch at (304) 616-4550. Select a category to proceed. Select the down arrow to expand the category. Select the same arrow to collapse the category. • How To Use This Guidebook • General Overview • Policies & Procedures ◦ Policies & Procedures Overview Contents 3 ◦ Import Requirements for Firearms & Ammunition ◦ ATF 4590 – Factoring Criteria for Weapons ◦ Restricted Importation ◦ Conditional