Expert Report of Dr. Allan J. Lichtman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Pre-Session Report

P R E - S E S S I O N R E P O R T 2 0 2 1 2021 PRE-SESSION REPORT Leading up to session, the First Amendment Foundation has analyzed legislation affecting your right of access to government proceedings and records. We are tracking more than 90 bills with open government and First Amendment implications. Many bills are repeats – from the exemption for records relating to the university and college president searches to the home address exemption for lawmakers – while some bills are specifically related to COVID-19. We have highlighted ten bills of particular interest. Additionally, we have included a brief summary of the other measures we are watching, organized by category. BILLS BY CATEGORIES This report was finalized on Wednesday, February 24th, Agriculture and does not include any bills filed by legislators after Court Records Criminal Justice & Law that date. We will continue to update our tracking lists Enforcement and weekly reports to include newly filed bills and keep Education you updated each Friday afternoon. Examinations & Investigations Bills FAF supports are in green, while bills FAF opposes Financial Information are in red. Otherwise, FAF has not taken a position on Health the legislation. An asterisk indicates FAF has suggested Home Addresses Personal Information or will suggest an amendment to narrow the scope of Public Meetings the exemption. Public Records Public Safety Voter Information Open Government Sunset Review P R E - S E S S I O N R E P O R T 2 0 2 1 LEGISLATION FAF SUPPORTS HB 913 Requests for Public Records/SB 400 Public Records Lawrence McClure (R-Plant City), Ray Rodrigues (R-Fort Myers) Prohibits an agency from filing a declaratory action against a person seeking public records to determine whether the records are exempt or confidential. -

2018 QUALIFIED CANDIDATES Florida Senate

2018 QUALIFIED CANDIDATES Florida Senate Senate District 2 Senate District 18 George Gainer (REP), incumbent Janet Cruz (DEM) Mary Gibson (DEM) Dana Young (REP), incumbent Senate District 4 Senate District 20 Aaron Bean (REP), incumbent Joy Gibson (DEM) Billee Bussard (DEM) John Houman (REP) Carlos Slay (REP) Tom Lee (REP), incumbent Joanna Tavares (LPF) Kathy Lewis (DEM) Senate District 6 Senate District 22 Audrey Gibson (DEM), incumbent Bob Doyel (DEM) Ricardo Rangel (DEM) Senate District 8 Kelli Stargel (REP), incumbent Kayser Enneking (DEM) Charles Goston (NPA) Senate District 23 (Special Election) Olysha Magruder (DEM) Faith Olivia Babis (DEM) Keith Perry (REP), incumbent Joe Gruters (REP) Senate District 10 Senate District 24 Michael Cottrell (DEM) Jeff Brandes (REP), incumbent Wilton Simpson (REP), incumbent Carrie Pilon (DEM) Senate District 12 Senate District 25 (Special Election) Dennis Baxley (REP), incumbent Gayle Harrell (REP) Keasha Gray (WRI) Belinda Keiser (REP) Gary McKechnie (DEM) Robert Levy (DEM) Senate District 14 Senate District 26 Dorothy Hukill (REP), incumbent Ben Albritton (REP) Melissa Martin (DEM) Catherine Price (DEM) Senate District 16 Senate District 28 Ed Hooper (REP) Annisa Karim (DEM) Leo Karruli (REP) Kathleen Passidomo (REP), incumbent Amanda Murphy (DEM) 1 2018 QUALIFIED CANDIDATES Senate District 30 Senate District 36 Rubin Anderson (DEM) Manny Diaz Jr (REP) Bobby Powell Jr (DEM), incumbent David Perez (DEM) Josh Santos (WRI) Julian Santos (DEM) Senate District 32 Senate District 38 Lauren Book (DEM), -

Primer on Anti-Immigrant Movement

October 15, 2015 Dear friends and colleagues, Anti-immigrant extremists are again pushing the GOP -- and the country -- toward zero- immigration policies. Their current standard-bearer, GOP presidential primary candidate Donald Trump, derives his immigration policy prescriptions almost verbatim from those posited by groups such as FAIR, CIS, Numbers USA and others like them. They have consistently opposed and undermined reasonable attempts to reform immigration policy. They will keep doing it, whether or not Mr. Trump captures the GOP presidential nomination. We believe that it’s in the best interest of immigration reformers, corporate America and the country to step up efforts to expose the nativist groups’ influence on policy formation, on the media, on the political process and on the government. Sunshine is, after all, the best disinfectant. It is especially important that the larger public know about the links these groups have to population control groups, in particular to proponents of eugenics. Only by exposing them can the process of marginalizing and ultimately defeating them take root. We hope that the enclosed report will deepen understanding of the politics of immigration reform and galvanize anew commitments to an inclusive, fair-minded and welcoming America. Feel free to share widely: we welcome your ideas, critique and suggestions. Rick Swartz ([email protected]) and Jocelyn McCalla ([email protected]) FROM KNOW-NOTHINGS1 TO KKK TO TANTON TO TRUMP PRIMER ON THE ANTI-IMMIGRANT FORCES DETERMINED TO HIJACK AMERICAN POLITICS By Rick Swartz and Jocelyn McCalla2 October 15, 2015 Anti-immigrant extremists are again pushing the GOP -- and the country -- towards zero- immigration policies. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions the Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions January 2019

January 2019 The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions The Department of Injustice Under Jeff Sessions January 2019 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 VOTING RIGHTS 2 IMMIGRANTS' RIGHTS 3 CRIMINAL JUSTICE 6 DISABILITIES 9 HEALTH CARE 10 RELIGIOUS LIBERTY 10 LGBT RIGHTS 10 CRIMINALIZATION OF POVERTY 11 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 12 WORKERS' RIGHTS 12 FREE PRESS AND PROTEST RIGHTS 12 PRIVACY RIGHTS 13 SEPARATION OF POWERS 15 POLITICIZED ANALYSIS AND PERSONNEL 15 INTRODUCTION Jeff Sessions' tenure at the Department of Justice was a national disgrace. As attorney general, he was entrusted to enforce federal laws — including civil rights laws — and secure equal justice for all. Instead, Sessions systematically undermined our civil rights and liberties, dismantled legal protections for the vulnerable and persecuted, and politicized the Justice Department's powers in ways that threaten American democracy. When President Donald Trump and his political appointees elsewhere in his administration tried to do the same, often in violation of the Constitution, Sessions' Justice Department went into overdrive manufacturing legal and factual justifications on their behalf and defending the unjust actions in court. Sessions was aided by Trump-approved appointees who often overruled career attorneys and staffers committed to a high level of neutral professionalism. Under Sessions' political leadership, these Trump appointees have inflicted significant damage in the past two years. Together they have threatened the First Amendment rights of the press and protesters, targeted the communities Trump disfavors through discriminatory policies and tactics, attacked the ability of ordinary citizens to vote and change their elected government, vindictively retaliated against perceived political opponents, and thwarted congressional oversight of the Justice Department's activities. -

Office Incumbent Challenger Party Contributions Loans In

2020 P7 Campaign Finance Report Cumulative Totals through August 13, 2020 Office Incumbent Challenger Party Contributions Loans In-Kinds Expenditures Cash on Hand SD01 Douglas Broxson REP $ 249,678.63 $ - $ 520.67 $ 70,664.68 $ 179,013.95 SD01 Karen Butler DEM $ 7,223.63 $ 1,114.45 $ - $ 2,790.50 $ 5,547.58 SD03 Loranne Ausley DEM $ 429,425.81 $ - $ 297,101.61 $ 106,672.93 $ 322,752.88 Benjamin Alexander Thaddeus Jon SD03 REP Horbowy $ 3,246.03 $ - $ - $ 1,835.20 $ 1,410.83 SD03 Marva Harris Preston REP $ 84,893.20 $ - $ 81,120.00 $ 28,083.50 $ 56,809.70 $ SD05 Melina Barratt DEM $ 5,273.81 $ - $ - $ 4,151.39 $ 1,122.42 SD05 Jennifer Bradley REP $ 506,295.00 $ - $ 3,607.70 $ 348,027.36 $ 158,267.64 SD05 Jason Holifield REP $ 15,143.30 $ 80,000.00 $ 1,110.16 $ 100,115.98 $ (4,972.68) SD07 Travis Hutson REP $ 239,855.60 $ - $ 520.67 $ 99,549.33 $ 140,306.27 SD07 Richard Dembinsky WRI $ - $ - $ - $ - $ - SD07 Heather Hunter DEM $ 7,223.20 $ - $ 46.85 $ 3,012.31 $ 4,210.89 SD09 Rick Ashby DEM $ 708.00 $ 3,092.74 $ - $ 1,557.53 $ 2,243.21 SD09 Jason Brodeur REP $ 743,635.31 $ - $ 342,495.81 $ 502,147.23 $ 241,488.08 SD09 Alexis Carter DEM $ 31,556.20 $ 5,000.00 $ - $ 12,058.73 $ 24,497.47 SD09 H. Alexander Duncan DEM $ 7,855.50 $ - $ 64.00 $ 5,320.26 $ 2,535.24 SD09 Jestine Iannotti # NPA SD09 Guerdy Remy DEM $ 7,914.00 $ 5,800.00 $ 2,753.38 $ 12,217.36 $ 1,496.64 SD09 Patricia Sigman DEM $ 242,965.60 $ - $ 202,073.54 $ 193,356.75 $ 49,608.85 SD11 Randolph Bracy DEM $ 116,701.51 $ - $ 170.79 $ 103,898.21 $ 12,803.30 SD11 Joshua E. -

NEW MEMBERS of the SENATE 1968-Present (By District, with Prior Service: *House, **Senate)

NEW MEMBERS OF THE SENATE 1968-Present (By District, With Prior Service: *House, **Senate) According to Article III, Section 15(a) of the Constitution of the State of Florida, Senators shall be elected for terms of 4 years. This followed the 1968 Special Session held for the revision of the Constitution. Organization Session, 1968 Total Membership=48, New Members=11 6th * W. E. Bishop (D) 15th * C. Welborn Daniel (D) 7th Bob Saunders (D) 17th * John L. Ducker (R) 10th * Dan Scarborough (D) 27th Alan Trask (D) 11th C. W. “Bill” Beaufort (D) 45th * Kenneth M. Myers (D) 13th J. H. Williams (D) 14th * Frederick B. Karl (D) Regular Session, 1969 Total Membership=48, New Members=0 Regular Session, 1970 Total Membership=48, New Members=1 24th David H. McClain (R) Organization Session, 1970 Total Membership=48, New Members=9 2nd W. D. Childers (D) 33rd Philip D. “Phil” Lewis (D) 8th * Lew Brantley (D) 34th Tom Johnson (R) 9th * Lynwood Arnold (D) 43rd * Gerald A. Lewis (D) 19th * John T. Ware (R) 48th * Robert Graham (D) 28th * Bob Brannen (D) Regular Session, 1972 Total Membership=48, New Members=1 28th Curtis Peterson (D) The 1972 election followed legislative reapportionment, where the membership changed from 48 members to 40 members; even numbered districts elected to 2-year terms, odd-numbered districts elected to 4-year terms. Organization Session, 1972 Redistricting Total Membership=40, New Members=16 2nd James A. Johnston (D) 26th * Russell E. Sykes (R) 9th Bruce A. Smathers (D) 32nd * William G. Zinkil, Sr., (D) 10th * William M. -

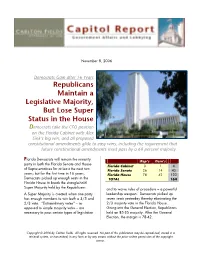

Capitol Report November 8, 2006

N ovem ber 8, 2006 Dem ocrats Gain after 16 Years Republicans M aintain a Legislative M ajority, But Lose Super Status in the House Dem ocrats take the CFO position on the Florida Cabinet with Alex Sink’s bi win! and all proposed constit"tional am endm ents lide to eas# wins! incl"din the re$"irem ent that f"t"re constit"tional am endm ents m "st pass b# a 6% percent m a&orit#' lorida D em ocrats w ill rem ain the m inority F Rep’s D em ’s party in both the Florida Senate and H ouse Florida Cabinet + # 4 of epresentatives for at least the ne!t tw o Florida Senate 26 #4 40 years" but for the first tim e in #6 years, Florida H ouse 38 42 #20 D em ocrats pic$ed up enou%h seats in the TO TA L 1 6 4 Florida H ouse to brea$ the stran%le&hold Super ' a(ority held by the epublicans) and to w aive rules of procedure 1 a pow erful * Super ' a(ority is created w hen one party leadership w eapon) D em ocrats pic$ed up has enou%h m em bers to w in both a +,- and seven seats yesterday thereby elim inatin% the 2,+ vote) ./!traordinary votes0 1 as 2,+ m a(ority vote in the Florida H ouse) opposed to sim ple m a(ority votes && are 2 oin% into the 2 eneral /lection, epublicans necessary to pass certain types of le%islation held an 8-&+- m a(ority) * fter the 2 eneral /lection, the m ar%in is 38&42) Copyright © 2006 by Carlton Fields. -

August 11, 2021 Dear Chairman Mcdaniel: We Are Proud to Present

August 11, 2021 Dear Chairman McDaniel: We are proud to present to you the Report of the Temporary Committee on Election Integrity (“Committee”). We are both honored that you entrusted us to lead this crucial initiative. Over the past six months, the Committee and subcommittees met regularly to review our election processes and the Republican Party’s role within them. We consulted numerous experts, tasked committee members with obtaining feedback from their states, conducted independent research, and deliberated over countless hours to develop this report. We hope our work on the Committee adds another chapter in our proud record as America’s party of voting rights and trustworthy elections. The Committee’s work can be broken down into three main functions. One, we wanted to learn from the past, so a post-mortem of the 2020 election was needed to ensure we could digest the unprecedented challenges and changes to strategize for the future. Two, we studied best policies and practices for election administration in order to make sound recommendations for state legislatures and policymakers. Third, we studied and made recommendations for the RNC’s and state parties’ role in protecting and promoting election transparency and voter integrity. We also want to ensure we recognize properly the work of the 24 Committee members who gave countless hours of their time and who made this report possible. We particularly want to thank our subcommittee chairs Jane Brady, Mark Kahrs, Debra Lamm, and Jason Thompson for their hard work drilling down into key topics. The subcommittees’ work provides a treasure trove of useful and valuable information that the RNC can utilize moving forward. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference Raise Their Hands in Solidarity with Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Protesters

Annual Report 2019-20 Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference raise their hands in solidarity with Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters The principles espoused by The Steamboat Institute are: Limited taxation and fiscal responsibility • Limited government • Free market capitalism Individual rights and responsibilities • Strong national defense Contents INTRODUCTION EMERGING LEADERS COUNCIL About the Steamboat Institute 2 Meet Our Emerging Leaders 18 Letter from the Chairman 3 MEDIA COVERAGE AND OUTREACH AND EVENTS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT Campus Liberty Tour 4 Media Coverage 20 Freedom Conferences and Film Festival 8 Social Media Analytics 21 Additional Outreach 10 FINANCIALS TONY BLANKLEY FELLOWSHIP 2019-20 Revenue & Expenses 22 FOR PUBLIC POLICY & AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM FUNDING About the Tony Blankley Fellowship 11 2019 and 2020 Fellows 12 Funding Sources 23 Past Fellows 14 MEET OUR PEOPLE COURAGE IN EDUCATION AWARD Board of Directors 24 Recipients 16 National Advisory Board 24 Our Team 24 The Steamboat Institute 2019-20 Annual Report – 1 – About The Steamboat Institute Here at the Steamboat Institute, we are Defenders of Freedom When we started The Steamboat Institute in 2008, it was and Advocates of Liberty. We are admirers of the bravery out of genuine concern for the future of our country. We take and rugged individualism that has made this country great. seriously the concept that freedom is never more than one We are admirers of the greatness and wisdom that resides generation away from extinction. in every individual. We understand that this is a great nation because of its people, not because of its government. The Steamboat Institute has succeeded beyond anything Like Thomas Jefferson, we would rather be, “exposed to we could have imagined when we started in 2008. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami.