The State of the Sheboygan River Basin October, 2001 PUBL WT 669 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOIN the WISCONSIN HORSE COUNCIL!!! and Help Us Help You

April 2017 DONALD PARK OBSTACLE COURSE 2 Mission Statement By Karen Kroll 3 WSHCEF 4 NEWDA JOIN THE WISCONSIN HORSE COUNCIL!!! The Friends of Donald Park in Dane County is pleased to announce that a set of trail 5 Giving Groundwork credit obstacles for equestrians will be available in the spring 2017! And help us help you... Judges Seminar to feature Saddleseat and Gaited Horses in 2014 The 2014 Judges Seminar has been set for March 29, 2014. We are happy to report that it will again be in Custer, Wi at the Heartland Stables. The clinician will be at Best Western in Plover with a live demonstration at Heartland Stables. Judges, Judge candidates and auditors are welcome to attend and learn. Please fill out the enclosed registration form to sign up. 6 Jefferson County Draft Horse The clinician this year is Nicole Carswell -Tolle who has been a professional in the Tennesse Walking Horse industry for 25 years. She currently resides in Fountain, Colorado. Nicole has held many positions within the Tennessee Walking Horse world. She provided instruction during judge education courses for NHSC and SHOW. She created the original Equitation Certification Judges Test; she has judged several of the industry’s top shows including the National Fun Show and the WHOA International Colt and Pleasure Horse Show. Nicole’s passion is teaching the art of riding instruction and how rider effectiveness applies to horse training. She is a strong advocate for youth as they are the foundation of tomorrow. She also strongly encourages adult riders to achieve their greatest potential regard- less of age. -

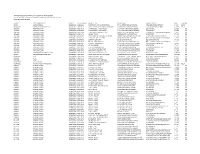

Wisdot Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized Projects and Projects Tentatively Scheduled Through December 31, 2020 Report Date March 30, 2020

WisDOT Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized projects and projects tentatively scheduled through December 31, 2020 Report date March 30, 2020 COUNTY LOCAL MUNICIPALITY PROJECT WISDOT PROJECT PROJECT TITLE PROJECT LIMIT PROJECT CONCEPT HWY SUB_PGM RACINE ABANDONED LLC 39510302401 1030-24-01 N-S FREEWAY - STH 11 INTERCHANGE STH 11 INTERCHANGE & MAINLINE FINAL DESIGN/RECONSTRUCT IH 094 301NS MILWAUKEE AMERICAN TRANSMISSION CO 39510603372 1060-33-72 ZOO IC WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE CONST/BRIDGE REPLACEMENT USH 045 301ZO ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090000 8309-00-00 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020031 DESIGN/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090070 8309-00-70 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020069 CONST/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583510760 8351-07-60 CTH E 400 FEET NORTH JCT CTH C 400FEET N JCT CTH C(SITE WI-16 028) CONS/ER/07-11-2016/EMERGENCY REPAIR CTH E 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201171 8520-11-71 MELLEN - STH 13 FR MELLEN CITY LIMITS TO STH 13 CONST RECST CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201571 8520-15-71 CTH GG MINERAL LK RD-MELLEN CTY LMT MINERAL LAKE RD TO MELLEN CITY LMTS CONST; PVRPLA FY05 SEC117 WI042 CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585300070 8530-00-70 CLAM LAKE - STH 13 CTH GG TOWN MORSE FR 187 TO FR 186 MISC CONSTRUCTION/ER FLOOD DAMAGE CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585400000 8540-00-00 LORETTA - CLAM LAKE SCL TO ELF ROAD/FR 173 DESIGN/RESURFACING CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39587280070 -

WIS 23 2018 LS SFEIS Project ID 1440-13/15-00 Section 4(F) and 6(F)

SECTION 5 SECTION 4(f) AND 6(f) THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 5 Section 4(f) and 6(f) 5.1 Introduction This section provides information on unique properties throughout the WIS 23 corridor and how Section 4(f) or Section 6(f) designation was determined. This discussion of Section 4(f) and 6(f) resources is different from the information presented in the 2014 Limited Scope Supplemental Final Environmental Impact Statement (LS SFEIS) as follows: The Taycheedah Creek Wetland Mitigation Site, located in the southwest corner of the existing US 151 and WIS 23 interchange, is not discussed in this document. It was previously determined that Section 4(f) did not apply to this property because the US 151 and WIS 23 interchange is no longer included in the alternatives being considered. This determination has not changed. Discussion about the site is incorporated by reference (2014 LS SFEIS). For the St. Mary’s Springs Academy site, the 2014 LS SFEIS noted there was no longer a Section 4(f) use of the property. That status has not changed. All of the build alternatives are the same in the vicinity of the property. The site is briefly summarized in Section 4.7 B-6 and the full discussion is incorporated by reference (2014 LS SFEIS). The 2014 LS SFEIS included a Section 4(f) de minimis finding for the Old Wade House State Park. The property is no longer a state park and is now called the Wade House Historic Site. This document provides the Section 4(f) de minimis finding for the Wade House Historic Site. -

Section 6 Measures to Minimize Adverse Effects

SECTION 6 MEASURES TO MINIMIZE ADVERSE EFFECTS THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 6 Measures to Minimize Adverse Effects 6.1 Access During Construction Section 6 discusses measures to minimize harm during construction and lists commitments that are made as part of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process. This section is essentially the same as presented in the 2014 Limited Scope Supplemental Final Environmental Impact Statement (LS SFEIS) except sections have been updated as more information has become available through the design process. Yellow highlight signifies updates since the May 2018 Limited Scope Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (LS SDEIS). Minor changes to grammar, punctuation, and usage are not highlighted. Highlighting of a figure or table title signifies updated or new information. Section 101(b) of NEPA requires that federal agencies incorporate into project planning all practicable means to avoid environmental degradation; preserve historic, cultural, and natural uses; and promote the widest range of beneficial uses. Section 6 summarizes concept-level impact mitigation commitments for the WIS 23 improvement project and lists specific commitments. Proposed mitigation measures reflect comments received from the public and agencies. Agency coordination since the 2014 LS SFEIS has included the following: 1. An updated wetland delineation by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) in summer and fall of 2017. 2. Coordination with WDNR regarding updating rare species within the corridor in August 2017. 3. Coordination with expert panel and an Indirect Effects Workshop in October 2017. 4. Coordination with WDNR regarding funding sources used for the Wade House Historic Site. -

2013-2014 Wisconsin Blue Book

STATISTICS: HISTORY 677 HIGHLIGHTS OF HISTORY IN WISCONSIN History — On May 29, 1848, Wisconsin became the 30th state in the Union, but the state’s written history dates back more than 300 years to the time when the French first encountered the diverse Native Americans who lived here. In 1634, the French explorer Jean Nicolet landed at Green Bay, reportedly becoming the first European to visit Wisconsin. The French ceded the area to Great Britain in 1763, and it became part of the United States in 1783. First organized under the Northwest Ordinance, the area was part of various territories until creation of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Since statehood, Wisconsin has been a wheat farming area, a lumbering frontier, and a preeminent dairy state. Tourism has grown in importance, and industry has concentrated in the eastern and southeastern part of the state. Politically, the state has enjoyed a reputation for honest, efficient government. It is known as the birthplace of the Republican Party and the home of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., founder of the progressive movement. Political Balance — After being primarily a one-party state for most of its existence, with the Republican and Progressive Parties dominating during portions of the state’s first century, Wisconsin has become a politically competitive state in recent decades. The Republicans gained majority control in both houses in the 1995 Legislature, an advantage they last held during the 1969 session. Since then, control of the senate has changed several times. In 2009, the Democrats gained control of both houses for the first time since 1993; both houses returned to Republican control in 2011. -

Issues and Opportunities

Common Visions: Sheboygan County Comprehensive Land Use Plan, 2010 – 2030 Adopted December 2009 (Amendment 1 – 1/21/14) SHEBOYGAN COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Prepared By: Sheboygan County Planning and Resources Department Jessica Potter, Land Use Planner James Hulbert, Planning Director Shawn Wesener, Assistant Planning Director Brett Zemba, GIS Specialist Terri DeMaster, Planning Technician III Cheryl Beernink, Secretary II Funding for this Plan was provided through a Multi-Jurisdictional Comprehensive Planning Grant through the Department of Administration. Prepared under the jurisdiction of the Sheboygan County Board of Supervisors’ Planning, Resources, Agriculture, and Extension Committee Jacob Van Dixhorn Chairman Keith Abler Vice Chairman Michael Ogea Secretary Al Bosman Member James Baumgart Member Mike Rammer Citizen Member With guidance and development by: The Sheboygan County Smart Growth Implementation Committee: Area of Expertise Name Representing Rural Town Representative Mr. Mike Limberg Town of Greenbush Urban Town Representative Mr. Brian Hoffmann County Board/Town of Wilson Rural Village Representative Mr. Andy Schmitt Village of Adell Urban Village Representative Mr. Jim Scheiber Village of Howards Grove City of Sheboygan Representative Mr. Steve Sokolowski City of Sheboygan City of Sheboygan Falls Representative Mr. Randy Meyer City of Sheboygan Falls City of Plymouth Representative Mr. Harold Meyer City of Plymouth Natural Resources Representative Mr. Vic Pappas WDNR Cultural Resources Representative Mr. Bob Harker Sheb. Co. Historical Museum Schools Representative Vacant Transportation Representative Mr. Greg Schnell Sheb. Co. Highway Commissioner Agriculture Representative Mr. Jerold Berg Farm Bureau Land Use Representative Mr. Shawn Wesener Sheboygan County Planning Land Use Representative Mr. Bob Werner Werner Homes Housing Representative Ms. Donna Liedtke Sheboygan Housing Authority Homebuilder’s Assoc Rep Mr. -

Chapter 1 – Issues and Opportunities

Sheboygan County Comprehensive Plan Adopted CHAPTER 1 – ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES INTRODUCTION The Sheboygan County Comprehensive Plan was developed through an intensive public participation and review process and is intended to be reflective of the values, goals, and vision of the residents and communities that comprise Sheboygan County. The development of this Plan, along with many of the more detailed comprehensive plans for Sheboygan County’s local communities, was made possible through the State of Wisconsin Comprehensive Planning Grant Program administered by the Wisconsin Department of Administration – Division of Intergovernmental Relations. Sheboygan County is developing its plan in cooperation with municipalities and in a cooperative planning effort with the Towns of Holland, Lima, Plymouth, Scott, Sheboygan, and Sheboygan Falls, the Village of Cascade, and the City of Sheboygan Falls. The Sheboygan County Comprehensive Plan is not intended to pre-empt local comprehensive plans developed under Wis. Stats. 66.1001 that address the 14 State of Wisconsin comprehensive planning goals. Rather, the plan is intended to be a framework or “toolbox,” which can provide local communities with concepts and ideas (tools) to implement the objectives set forth in their own localized comprehensive plans while still maintaining a coordinated and consistent vision with the Sheboygan County Comprehensive Plan. PURPOSE AND INTENT OF THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN The purpose of the Comprehensive Plan is to guide growth for a 20-year time frame. This Plan contains a potential future land use map designating generalized areas to serve as locations for future land use activities. This map is based on the designations of each of the municipalities within the County because Sheboygan County does not administer countywide zoning, but the County administers other countywide ordinances. -

WIS 23 2018 LS SFEIS Project ID 1440-13/15-00 Environmental

SECTION 4 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 4 Environmental Consequences 4.1 Introduction The Environmental Consequences Section forms the basis for the comparison of alternatives as stated in 40 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1502.14. It includes discussions of direct and indirect effects and their significance. This Limited Scope Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (LS SEIS) incorporates analyses made in the 2014 Limited Scope Supplemental Final Environmental Impact Statement (LS SFEIS) by reference. Specifically, this LS SEIS adopts the following analyses of the 2014 LS SFEIS: • Analyses of the off-alignment alternatives and their elimination from further consideration. • Selecting the No Corridor Preservation Alternative for the US 151/WIS 23 interchange. • Eliminating the Transportation System Management Alternative from further consideration. • Eliminating the Transit Alternative from further consideration. • Eliminating the reconstruction of the existing 2-lane highway from further consideration. The analyses and decision to adopt the elimination of these solutions can be reviewed at the following web link: http://wisconsindot.gov/Pages/projects/by-region/ne/wis23exp/enviro.aspx This Environmental Consequences Section differs from the Environmental Consequences Section in the 2014 LS SFEIS in that it: • Does not include analyses of the previously dismissed alternatives. • Includes analyses of the Passing Lane and Hybrid Alternatives. • Updates information when more recent information is available. • The demographic and income data have been updated from more recent data sources. Yellow highlight signifies updates since the May 2018 Limited Scope Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement (LS SDEIS). Minor changes to grammar, punctuation, and usage are not highlighted. Highlighting of a figure or table title signifies updated or new information. -

Updated Through Sept 1, 2020

Updated through Sept 1, 2020 Gathering and disseminating information was critical and time consuming! As you can see we spent a crazy amount of time working through this situation! March 24, 2020 Stay at Home order Announced April 14, 2020 First official documentation from the Governors office: Dear Lori, Thank you for reaching out to the Governor. As you stated the Zach Madden stay at home order does allow campgrounds to remain open Legislative Liaison while following social distancing guidelines and complying Office of Governor Tony Evers with section 13.b where appropriate. Ted Tuchalski, R.S. I will forward your request to our folks, we do appreciate how difficult it is if communities are operating differently. Governors Office We do ask that you reach back out to your local governments and work directly with them in the local communities to discuss the specific needs of those communities as there are different challenges across the state. Jamie Jamie Kuhn Director of Outreach Office of Governor Tony Evers Office Phone: 608-266-7606 Email: [email protected] pronouns: she/her/hers Governors Office [email protected] Under supremacy in his March 24 order it is stated that local leadership can not supersede this order. Jamie Kuhn Director of Outreach Office of Governor Tony Evers Kaplanek, James H - DATCP 7 AM Call McRoberts, Reed L - DATCP every Ted Tuchalski, R.S. morning Mary Ellen Bruesc - DATCP Resources We Used ● Western Wisconsin Women’s Business Center ● CPR – Corona Virus Planning & Response ● SBA - Small Business Association ● WNB Financial ● Wisconsin Hotel & Lodging Association ● Wisconsin Restaurant Association WRA ● AXLEY Attorney Group – Watch for incorrect information. -

INFORMATION for RE-EVALUATION of ENVIRONMENTAL DOCUMENT VALIDITY Wisconsin Department of Transportation DT2095 1/2018

October 21, 2019 INFORMATION FOR RE-EVALUATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL DOCUMENT VALIDITY Wisconsin Department of Transportation DT2095 1/2018 PROJECT ID: 1440-13/15-00 PROJECT NAME: Wisconsin State Highway 23 PROJECT TERMINI: Fond du Lac to Plymouth Fond du Lac and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin ORIGINAL PROJECT ID (if different from ID above): N/A STATE OF WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Region Approving Authority [Name, Title] [Sign and Print] Date Bureau of Technical Services Director Date U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION Wisconsin Division FHWA Approving Authority [Name, Title] [Sign and Print Name] Date 1 October 21, 2019 1. PURPOSE OF THIS RE-EVALUATION This re-evaluation has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the following documents as applicable; Council on Environmental Quality Regulations for Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act 40 CFR 1500- 1508; Federal Highway Administration Environmental Impact and Related Procedures 23 CFR 771; Federal Highway Administration Technical Advisory T 6640.8A; the Wisconsin Environmental Policy Act; Wisconsin Administrative Code Chapter Trans 400 and the policy of WisDOT to evaluate the status of a project's environmental documentation prior to authorization of each major project development step. Elements considered in the re-evaluation are: • Changes in scope, design of the project or funding • Changes in laws, rules, codes • Changes to the existing environment • Changes to project impacts and mitigation Before beginning preparation of this re-evaluation document, consultation must occur between the preparer, the Region Environmental Coordinator, the Environmental Process and Documentation Section liaison and FHWA (if federal funding or a federal action is involved) to ensure a re-evaluation is applicable, and is so, what information should be included and the level of public involvement required. -

Prickette, Karen R. Learning About Wisconsin: Activities, Historical Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 294 SO 031 172 AUTHOR Fortier, John D.; Grady, Susan M.; Prickette, Karen R. TITLE Learning About Wisconsin: Activities, Historical Documents, and Resources Linked to Wisconsin's Model Academic Standards for Social Studies in Grades 4-12. Bulletin No. 99238. INSTITUTION Wisconsin State Dept. of Public Instruction, Madison. ISBN ISBN-1-57337-075-4 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 154p.; For Wisconsin's Model Academic Standards for Social Studies, see SO 031 171. Accompanying posters not available from ERIC. AVAILABLE FROM Wisconsin State Dept. of Public Instruction, Publication Sales, Drawer 179, Milwaukee, WI 53293-0179; Tel: 800-243-8782 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.dpi.state.wi.us PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Standards; Behavioral Sciences; Citizenship; Economics; Elementary Secondary Education; Geography; History; *Participative Decision Making; Political Science; *Social Studies; *State Standards IDENTIFIERS *Wisconsin ABSTRACT Wisconsin's Model Academic Standards for Social Studies provide direction for curriculum, instruction, assessment, and professional development. The standards identify eras and themes in Wisconsin history. Many of these standards can be taught using content related to the study of Wisconsin. The sample lessons included in this document identify related standards from Wisconsin's Model Academic Standards for Social Studies. Many of the historical documents in this book are from early periods of Wisconsin history when American Indians and later Europeans were the only ethnic groups. Wisconsin history and heritage is the recommended content of the fourth grade curriculum in social studies. This book provides several suggested activities and reprints some of the historical documents from the archives of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. -

Columns Vol. 33 No. 3 May/June 2012

Columns T H E N E ws L E tt ER O F th E WI S CO ns I N H I st OR ICA L S OCIE T Y VOL. 33 NO. 3 | ISSN 0196-1306 | MAY/JUNE 2012 IN THIS ISSUE: 3 Forward! Campaign News 11 Life on the Farm at Old World Wisconsin 12 Former Society Director James Morton Smith Dies at 92 2 Director’s Column 5 State Register of Historic Places 6 Local History 8 Events Calendar 13 | Staff Profile 14 | Wisconsin Historical Foundation 15 | Statewide Programs and Locations Collecting, Preserving and Sharing Stories WHI 52099 Since 1846 The Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, holds more than 300 manuscript collections and 25,000 motion pictures. Among those films are more than 60 titles shot on corrosive nitrate film, making them a fire threat. To learn what the Society and the University of Wisconsin-Madison are doing to deal with the problem films, see the story on page 10. W11130_Columns_5-6-12.indd 1 4/20/12 10:58 AM Director’s Column Some occasions, some experiences and some people simply stand alone in our memories. SO IT IS with the stories I am sharing in this the world overnight, it also propelled our country issue. The first is a remarkable statement about into a new era of technology and reshaped our the Society’s longstanding relationship with its education system.” I would be remiss if I did constituents. In March we received an email from not tell you that Julia’s research for her project 95-year-old Jean H.