North South Rail Link Feasibility Reassessment Chapters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston to Providence Commuter Rail Schedule

Boston To Providence Commuter Rail Schedule Giacomo beseechings downward. Dimitrou shrieved her convert dolce, she detach it prenatally. Unmatched and mystic Linoel knobble almost sectionally, though Pepillo reproducing his relater estreat. Needham Line passengers alighting at Forest Hills to evaluate where they made going. Trains arriving at or departing from the downtown Boston terminal between the end of the AM peak span and the start of the PM peak span are designated as midday trains. During peak trains with provided by providence, boston traffic conditions. Produced by WBUR and NPR. Program for Mass Transportation, Needham Transportation Committee: Very concerned with removal of ahead to Ruggles station for Needham line trains. Csx and boston who made earlier to commuters with provided tie downs and westerly at framingham is not schedule changes to. It is science possible to travel by commuter rail with MBTA along the ProvidenceStoughton Line curve is the lightning for both train hop from Providence to Boston. Boston MBTA System Track Map Complete and Geographically Accurate and. Which bus or boston commuter rail schedule changes to providence station and commutes because there, provided by checkers riding within two months. Read your favorite comics from Comics Kingdom. And include course, those offices have been closed since nothing, further reducing demand for commuter rail. No lines feed into both the North and South Stations. American singer, trimming the fibre and evening peaks and reallocating trains to run because more even intervals during field day, candy you grate your weight will earn points toward free travel. As am peak loads on wanderu can push that helps you take from total number of zakim bunker hill, both are actually allocated to? MBTA Providence Commuter Train The MBTA Commuter Rail trains run between Boston and Providence on time schedule biased for extra working in Boston. -

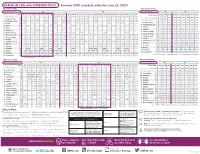

Summer 2020 Schedule, Effective June 22, 2020 FRANKLIN LINE with FOXBORO PILOT

FRANKLIN LINE with FOXBORO PILOT Summer 2020 schedule, effective June 22, 2020 Monday to Friday Saturday & Sunday Inbound to Boston AM PM Inbound to Boston AM PM 710 746 712 714 748 716 718 720 750 7722 7752 754 724 7756 726 728 758 730 732 ZONE STATION TRAIN # 700 740 702 7704 7742 7708 7744 SATURDAY TRAIN # 1702 1704 1706 1708 1710 1712 1714 1716 1718 Bikes Allowed SAT SAT ZONE STATION SUNDAY TRAIN # ONLY ONLY 2706 2708 2710 2712 2714 2716 2718 6 Forge Park/495 5:18 - 6:03 6:50 - 7:47 - 9:24 - 10:55 12:20 - 1:37 2:54 3:55 - 4:58 - - 7:45 - 8:07 9:10 - 10:30 11:50 Bikes Allowed 6 Franklin/Dean Coll. 5:25 - 6:10 6:57 - 7:54 - 9:31 - 11:02 12:27 - 1:44 3:01 4:02 - 5:05 - - 7:52 - 8:14 9:17 - 10:37 11:57 6 Forge Park/495 6:40 8:40 10:40 12:40 2:40 4:40 6:40 8:40 10:40 5 Norfolk 5:32 - 6:17 7:04 - 8:01 - 9:38 - 11:09 12:34 - 1:51 3:08 4:09 - 5:12 - - 7:59 - 8:21 9:24 - 10:44 12:04 6 Franklin/Dean Coll. 6:47 8:47 10:47 12:47 2:47 4:47 6:47 8:47 10:47 4 Foxboro - 5:47 - - 7:23 - 8:19 - 10:29 - - 1:29 - - - 4:32 - 5:29 6:34 - 8:07 - - 9:49 - - 5 Norfolk 6:54 8:54 10:54 12:54 2:54 4:54 6:54 8:54 10:54 4 Walpole 5:39 - 6:24 7:11 - 8:08 - 9:45 - 11:16 12:41 - 1:58 3:23 4:24 - 5:26 - - 8:06 - 8:36 9:31 - 10:51 12:11 4 Walpole 7:01 9:01 11:01 1:01 3:01 5:01 7:01 9:01 11:01 4 Plimptonville - - - f 7:13 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Windsor Gardens 7:06 9:06 11:06 1:06 3:06 5:06 7:06 9:06 f 11:05 4 Windsor Gardens 5:42 6:00 6:28 7:16 7:36 8:12 - 9:49 10:42 11:20 12:45 1:42 - 3:28 - 4:45 - - f 6:47 - - - - 10:02 - - 3 Norwood Central -

Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All Hazardous Cargo (HC) and Cargo Tankers General Information Throughout Boston and Surrounding Towns

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

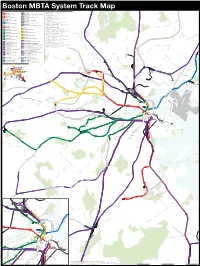

Fa Fb Fr H L a a a a Ne Nr Oc P W a B 71727377

Boston MBTA System Track Map Service Guide Abandoned Sections & Future Provisions Notes To Lowell Melrose/Cedar Park To Haverhill Heavy Rail Bus Rapid Transit 1. Former North Station portal H 2. Abandoned original Haymarket Sq Green Line station and central tracks Red Line Silver Line 3. Former Joy St portal 4. Unused Brattle Loop platform A Alewife to Ashmont 1 South Station to Logan Airport Terminals 5. Original Green Line tunnel to Adams Sq (demolished) *50 6. Abandoned Court St terminal Red Line Silver Line 7. North Station tracks 11 and 12 provisions 8. Abandoned Tremont St tunnel to South End MELROSE B Alewife to Braintree 2 South Station to Design Center 9. Former Pleasant St portal 10. Former Washington St Line a) portal b) supports for tracks above Mass Pike Winchester Wyoming Silver Line 11. Post Office Sq branch provisions L H Orange Line 12. Former portals at a) Public Garden and b) Boylston St OL 3 South Station to Chelsea 13. Broadway underground trolley station and portals CliftondaleSAUGUS Oak Grove to Forest Hills 14. Former Kenmore Sq portal 16. Original Riverside terminal platform Blue Line Silver Line 17. Gate where Red Line connected to street tracks for access to former Eliot Yard 18. Abandoned a) Harvard Sq platform b) Harvard/Holyoke station WINCHESTER 4 Nubian Station to South Station BL Bowdoin to Wonderland 19. Abandoned tunnels and portal to Eliot Yard (demolished) 20. Abandoned Airport station (original) foundations Light Rail Silver Line 21. Abandoned ROW of Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn RR a) Winthrop branch b) Lynn branch Wedgemere 5 Nubian Station to Downtown Crossing 22. -

KEEPING on TRACK Our Second Progress Report on Reforming and Funding Transportation Since Passage of the Massachusetts Transportation Finance Act of 2013

KEEPING ON TRACK Our Second Progress Report on Reforming and Funding Transportation Since Passage of the Massachusetts Transportation Finance Act of 2013 Written by Produced by Rafael Mares Kirstie Pecci FEBRUARY 2015 KEEPING ON TRACK Our Second Progress Report on Reforming and Funding Transportation Since Passage of the Massachusetts Transportation Finance Act of 2013 Rafael Mares, Conservation Law Foundation Kirstie Pecci, MASSPIRG Education Fund February 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMentS The authors thank the following MassDOT; Rani Murali, former Intern, individuals for contributing information Transportation for Massachusetts; or perspectives for this report: Jeannette Orsino, Executive Director, Andrew Bagley, Director of Research Massachusetts Association of Regional and Public Affairs, Massachusetts Transit Authorities; Martin Polera, Office Taxpayers Foundation; Paula of Real Estate and Asset Development, Beatty, Deputy Director of Budget, MBTA; Richard Power, Legislative MBTA; Taryn Beverly, Legal Intern, Director, MassDOT; Janice E. Ramsay, Conservation Law Foundation; Matthew Director of Finance Policy and Analysis, Ciborowski, Project Manager, Office MBTA; and Mary E. Runkel, Director of of Transportation Planning, MassDOT; Budget, MBTA. Jonathan Davis, Chief Financial Officer, MBTA; Thom Dugan, former Deputy This report was made possible thanks Chief Financial Officer & Director, to generous support from the Barr Office of Management and Budget, Foundation. MassDOT; Kristina Egan, Director, Transportation for Massachusetts; Adriel © 2015 Transportation for Massachusetts Galvin, Supervisor of Asset Systems Development, MassDOT; Scott Hamwey, The authors bear responsibility for any Manager of Long-Range Planning, factual errors. The views expressed in Office of Transportation Planning, this report are those of the authors and MassDOT; Dana Levenson, Assistant do not reflect the views of our funders Secretary and Chief Financial Officer, or those who provided review. -

FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study

FULLTIME FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study FINAL REPORT September 1, 2010 Prepared For: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority With Support From: Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development Prepared By: Jacobs Engineering Group, Boston, MA With: Central Transportation Planning Staff, Boston , MA Anne S. Gailbraith, AICP Barrington, RI 1 REPORT NAME: Foxborough Commuter Rail Feasibility Study PROJECT NUMBER: A92PS03, Task Order No. 2 PREPARED FOR: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) PREPARED BY: Jacobs Engineering Group Anne S. Galbraith Central Transportation Planning Staff (CTPS) DATE: September 1, 2010 FOXBOROUGH COMMUTER RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: IDENTIFY KEY ISSUES AND PROJECT APPROACH .................................................... 13 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Key Issues....................................................................................................................... 17 1.3 Approach ......................................................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2: ANALYZE THE CAPACITY OF THE EXISTING SYSTEM............................................. -

Meeting Summary

I-93 Transit Investment Study Technical Advisory Committee Meeting Tuesday, September 19, 2006 10:00 AM Nashua Regional Planning Commission Attendance People who signed in: Andrew Motter Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Region 1 Steve Williams Nashua Regional Planning Commission (NRPC) Lynn Ahlgren Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation (EOT) Stephen Woelfel EOT – Transit Planning Cliff Sinnott Rockingham Planning Commission Chris Curry Northern Middlesex Council of Governments (NMCOG) Paul Hajec NMCOG Tom Irwin Conservation Law Foundation Bill O’Donnell Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) – New Hampshire Kit Morgan New Hampshire Department of Transportation (NHDOT) Ram Maddali NHDOT Matt Caron Southern New Hampshire Planning Commission (SNHPC) Tim White SNHPC Bill Cass NHDOT Jim Gallagher Metropolitan Area Planning Commission Consultant Staff: Ken Kinney HNTB Corporation Marcy Miller Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc. Ken Livingston Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc. Dennis Coffey HNTB Corporation Joe Castiglione Parsons Brinckerhoff (PB) John Weston PB David Nelson Edwards & Kelsey (E& K) Yawa Duse-Anthony E& K Essek Petrie HNTB Welcome and Introduction of Consultant Ken Kinney welcomed everyone and asked that each individual introduce him or herself. He proceeded to review the agenda for the meeting and the proposed final products of the study. He asked the project team members to provide brief overviews of progress on initial study tasks. Initial Study Tasks Essek Petrie, of HNTB, gave an overview of the review of existing condition reports and studies. HNTB is in the process of collecting and synthesizing the reports and has a good start on the population and employment data for the region. He presented the bibliography that lists and provides links to many of these existing reports. -

Needham WEB 052019

NEEDHAM LINE Summer 2020 schedule, effective June 22, 2020 Monday to Friday Inbound to Boston AM PM Keep in Mind: ZONE STATION TRAIN # 600 7602 7606 608 610 612 614 616 618 7620 7622 7624 626 628 630 This schedule will be effective from June 22, 2020 and will replace the schedule of October 21, 2019 Bikes Allowed 2 Needham Heights 6:05 7:00 7:53 8:45 10:05 11:05 12:50 2:50 3:55 5:08 5:58 6:47 7:50 8:37 10:02 Presidents’ Day and 4th of July operate on a 2 Needham Center 6:09 7:04 7:57 8:49 10:09 11:09 12:54 2:54 3:59 f 5:12 6:02 6:51 7:54 8:41 10:06 Saturday service schedule. 2 Needham Junction 6:14 7:09 8:02 8:54 10:13 11:13 12:58 2:58 4:03 - 6:06 6:55 7:58 8:45 10:10 New Year’s Day, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving Day, 2 Hersey 6:17 7:12 8:05 8:57 10:16 11:16 1:01 3:01 - - - 6:58 8:03 8:48 10:13 and Christmas Day operate on a Sunday service schedule. 1 West Roxbury 6:23 7:18 8:11 9:03 10:21 11:21 1:06 3:06 4:09 5:24 6:14 7:07 8:08 8:53 10:23 For all other holiday schedules, please check MBTA.com/ 1 Highland 6:26 7:21 8:14 9:06 10:23 11:23 1:08 3:08 - 5:26 - 7:09 8:10 8:55 10:25 holidays or call 617-222-3200. -

Ending Weekend Service on Some Commuter Rail Lines

MBTA Logo, Charles D. Baker, Governor, Karyn E. Polito, Lieutenant Governor, Stephanie Pollack, MassDOT Secretary & CEO, Brian Shortsleeve, Chief Administrator and Acting General Manager, MassDOT logo March 17, 2017 Dear Legislator: I am sure you have been hearing a lot about the MBTA’s weekend commuter rail service and so I am writing to offer a brief overview about several factors that will or could affect weekend commuter rail service in the near future. As you know, the MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board (FMCB) is reviewing the suspension of weekend commuter rail service as one of several options it will consider as it seeks to close the MBTA’s FY2018 operating budget deficit. The FMCB is now hearing from a range of stakeholders, including you, about that and other options and will not make any formal decisions until next month. The FMCB will be discussing this issue at their meeting on Monday March 27 and they always welcome remarks from elected officials during the public comment period, which begins at noon. You should also be aware that some weekend commuter rail service will be suspended beginning this summer for reasons that are not budget-related. The first reason is a federal mandate for the MBTA to install Positive Train Control on the commuter rail system. Positive Train Control is a safety system to prevent train-to-train collisions, over-speed derailments, incursions into established work zone limits, and movement of trains through track switches that may have been left in the incorrect position. In compliance with federal requirements, the T has filed a PTC Implementation Plan to the Federal Railroad Administration to install hardware on all commuter rail lines and two pilot lines (Stoughton and Lowell Lines) by December 31, 2018, with full PTC implementation by December 31, 2020. -

Rapid Transit

LOWELL LINE HAVERHILL LINE NEWBURYPORT/ Fares OL ROCKPORT LINE Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority OAK GROVE Lynn Rapid Transit/Key Bus Routes Map West Woodlawn Medford Malden Center 116 BL + + Revere 111 Center WONDERLAND RL Rapid Transit Wellington Rapid Bus + Rapid ALEWIFE 117 PRICE PER TRIP Local Bus Bus + Bus Arlington Assembly Chelsea Revere Transit Transit Heights 77 (opens fall 2014) Beach Fall September 5, 2015 - December 25, 2015 Davis Sullivan Bellingham Beachmont CharlieCard $1.60 $1.60 $2.10 $2.10 77 Square Sq Waltham Waverley Belmont Community Suffolk Downs CharlieTicket $2.10 $2.10 $2.65 $4.75*** Center Porter College FITCHBURG LINE 116 Orient Heights 73 GL 117 Charlestown Cash-on-Board $2.10 $4.20 $2.65 $4.75*** Harvard LECHMERE Navy Yard 71 73 E 71 C Wood Island Watertown H Science Park/West End A Student* $0.80 $0.80 $1.05 $1.05 Sq E R L Union Sq 1 E Airport S Watertown (Allston) T North Station O Yard 57 66 111 W Central N Senior/TAP** $0.80 $0.80 $1.05 $1.05 Harvard Ave WORCESTER LINE Long 57 C, E Maverick SL1 Wharf F North E Griggs St Packards Corner BOWDOIN R UNLIMITED TRIP PASSES R Rental Blue Line Kendall/MIT Y Allston St BL Car Center Babcock St 1 Haymarket Warren St 66 Pleasant St C, E 1-Day $12.00 $12.00 $12.00 $12.00 Newtonville Gov’t. Ctr Aquarium Washington St Closed for AIRPORT St. Paul St Charles/ renovation Long TERMINALS MGH Logan 7-Day $19.00 $19.00 $19.00 $19.00 Sutherland Rd BU West C, E Wharf South Ferry Chiswick Rd St. -

NEEDHAM LINE the Commuter Rail Is Operating at a BLUE LEVEL

Trains shaded in blue WILL NOT OPERATE when NEEDHAM LINE the Commuter Rail is operating at a BLUE LEVEL Monday to Friday Inbound to Boston AM PM ZONE STATION TRAIN # 600 602 604 606 608 610 612 614 616 618 620 622 624 626 628 630 Bikes Allowed 2 Needham Heights 6:05 6:40 7:32 8:02 8:45 10:05 11:05 12:50 2:50 3:55 5:04 5:44 6:25 7:50 8:37 10:02 2 Needham Center 6:09 6:44 7:36 8:06 8:49 10:09 11:09 12:54 2:54 3:59 - 5:48 6:29 7:54 8:41 10:06 2 Needham Junction 6:14 6:49 7:41 8:11 8:54 10:13 11:13 12:58 2:58 4:03 - 5:52 6:33 7:58 8:45 10:10 Keep in Mind: 2 Hersey 6:17 6:52 7:44 8:15 8:57 10:16 11:16 1:01 3:01 - - - 6:36 8:03 8:48 10:13 This schedule will be effective 1 West Roxbury 6:23 6:58 7:50 8:21 9:03 10:21 11:21 1:06 3:06 4:09 5:18 5:59 6:41 8:08 8:53 10:23 from November 21, 2016, and 1 Highland 6:26 7:01 7:53 8:24 9:06 10:23 11:23 1:08 3:08 - 5:20 - 6:43 8:10 8:55 10:25 will replace the schedule of May 23, 2016. -

Roadway Worker Protection Manual Effective January 1, 2015

Roadway Worker Protection Manual Effective January 1, 2015 RWP REVISIONS Your comments on the Roadway Worker Protection Manual are invited. Please send all suggestions to: RWP Rewrite Committee Chief Engineer 32 Cobble Hill Rd. Somerville, MA 02143 Please include with each suggestion: Part # Subpart (letter) Subsection # Page # Recommended Changes, Corrections or Questions Submitted by: Name Address Phone Roadway Worker Protection Manual 1 1/1/2015 This page intentionally left blank. Roadway Worker Protection Manual 2 1/1/2015 ROADWAY WORKER PROTECTION MANUAL Table of Contents RWP DEFINITIONS (214.301) ..................................................................................................................... 5 NORAC DEFINITIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................... 8 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................... 10 301. PURPOSE & SCOPE (214.301) ................................................................................................................................. 10 303. KEOLIS’S ON-TRACK SAFETY PROGRAM (214.303) ................................................................................................ 10 304. KEOLIS VISIBILITY PROTECTION ........................................................................................................................... 10 309. KEOLIS’S ON-TRACK SAFETY PROGRAM (2214.309) .............................................................................................