Hello Please Find the Attached Hearing Submission Regards Mary Sparrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kaiapoi Street Map

Kaiapoi Street Map www.northcanterbury.co.nz www.visitwaimakariri.co.nz 5 19 To Woodend, Kaikoura and Picton North To Rangiora T S S M A I L L I W 2 D R E 62 D I S M A C 29 54 E V A 64 E To Pines, O H and Kairaki 52 U T 39 45 4 57 44 10 7 63 46 47 30 8 32 59 9 38 33 24 65 11 37 66 48 18 16 23 61 26 20 17 27 25 49 13 58 14 12 28 21 51 15 22 31 41 56 50 55 3 1 35 Sponsored by 36 JIM BRYDEN RESERVE LICENSED AGENT REAA 2008 To Christchurch Harcourts Twiss-Keir Realty Ltd. 6 MREINZ Licensed Agent REAA 2008. Phone: 03 327 5379 Email: [email protected] Web: www.twisskeir.co.nz 40 60 © Copyright Enterprise North Canterbury 2016 For information and bookings contact Kaiapoi i-SITE Visitor Centre Kaiapoi Street and Information Index Phone 03 327 3134 Adams Street C5 Cressy Ave F3 Lees Rd A5 Sneyd St F2 Accommodation Attractions Adderley Tce E2 Cridland St E4 Lower Camside Rd B4 Sovereign Bvd C5 1 H3 Blue Skies Holiday & Conference Park 32 F4 Kaiapoi Historic Railway Station Akaroa St G3 Cumberland Pl H2 Magnate Dr C5 Stark Pl D5 2 C4 Grenmora B & B 55 Old North Rd 33 F4 Kaiapoi Museum And Art Gallery Aldersgate St G2 Dale St D4 Magnolia Bvd D5 Sterling Cres C5 3 H3 Kaiapoi on Williams Motel 35 H3 National Scout Museum Alexander Ln F3 Davie St F4 Main Drain Rd D1 Stone St H4 64 F6 Kairaki Beach Cottage 36 H5 Woodford Glen Speedway Allison Cres D5 Dawson Douglas Pl G4 Main North Rd I3 Storer St F1 4 F3 Morichele B & B Alpine Ln F3 Day Pl F5 Mansfield Dr G3 Sutherland Dr C6 5 A5 Pine Acres Holiday Park & Motels Recreation Ansel Pl D5 Doubledays -

Two Into One – Compiled by Jean D.Turvey

Two Into One – compiled by Jean D.Turvey Page 1 Two Into One – compiled by Jean D.Turvey Page 2 Two Into One – compiled by Jean D.Turvey Published by Kaiapoi Co-operating Parish 53 Fuller Street Kaiapoi Email - [email protected] ISBN 0-476-00222-2 ©Copyright Kaiapoi Co-operating Parish, February 2004 Printed by Wickliffe Print 482 Moorhouse Avenue Christchurch PREFACE This is a story of three parishes - one Methodist, one Presbyterian, and one Co- operating - worshiping and witnessing in Kaiapoi in three different centuries. It starts with pioneer settlers in a small village half a world away from their homes. It ends - at least this part of the story does - in a burgeoning satellite town. Letters and news originally took months to arrive. Now they are as instant as emails and television. However, through the dramatic changes of the last 150 years runs the common thread of faith. This is a story which needs to be read twice. The first time, read what Jean Turvey has written. In any history there are those people who stand out because of their leadership, strong personalities, or eccentricities. Ministers loom large, simply because they are involved in most aspects of parish life. Buildings feature, because they provide a focal point for congregational life. The second reading of this history is more difficult. You need to read between the lines, to focus on what is not written. The unrecorded history of these three parishes is just as vital as the narration of obvious events and personalities. It consists of people whose names are unknown, but who worshipped faithfully and gave life to these local churches. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

2686··· THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 99 !UI,ITARY AREA No. 10 (CHRISTCHURCH)-oontiooed. MILITARY AREA No. 10 (CHRISTCHURCH)-contiooecl. 632787 Baxter, Alan Clifford, apprentice carpenter, 57 Ayers St., 633651 Billings, Edwin Cleve, brass-finisher, 43 Ryan St. Rangiora, North Canterbury. 562855 Bilton, Claud Hamilton, tramway motorman, 110 Charles St., 632802 Baxter, Colin James, farm hand, Waddington, Darfield Linwood. R.M.D. 584929 Binnie, Fredrick George, surfaceman, Ohoka. 494916 Baxter, John Walter, motor-driver, 220 Everton Rd., 460055 Binnie, James, shepherd, "Rocky Point," Hakataramea. Brighton. 599480 Binnie, Joha, fitter (N.Z.R,}, 71 Wainui St., Riccarton. 494956 Baylis, Ernest Henry, club steward, 42 Mersey St. 559354 Binning, Herbert Geoffrey, millwright, 24 Stenness Ave., 632012 Baylis, Gordon Francis, service-station attendant, Irwell. Spreydon. R.D., Leeston. 562861 Birchfield., Samuel Matthew, dairy-farmer, 52 Cooper's Rd., 606927 Baynon, Harold Edward, farmer, R.M.D., Lo burn, Rangiora. Shirley. 466654 Beach, Roland Alfred Benjamin, clerk, 75 Otipua Rd., 559330 Bird, Norman Frederick Wales, ganger (N.Z.R.), 21 Horatio Timaru. St. 530811 Beal, Frederick Mark, farmer, East Eyreton. 574074 Birdling, Harley Albert, shepherd, Poranui Post-office. 504942 Beale, Erle Leicester, brewery employee, 106 Randolph 610034 Birdling, Huia William, traffic officer, 70 Cleveland St., St., Woolston. · Shirley. 472302 Beard, Albert George, police constable, 180 Brougham St., 517153 Bishell, Ira Francis, general labourer, Horsley Downs, Sydenham. Hawarden. 551259 Bearman, Wilfrid James, painter, 37 Birdwood Ave., 562868 Bishell, Victor David, farmer, Medbury, Hawarden. Beckenham. 559602 Bishop, George Blackmore, farm labourer, Dorie R.D., 520002 Bearne, Frederick Vaughan, carriage-builder, 66 Birdwood Rakaia. Ave. 558551 Bishop, Henry, dairy-farmer, 21 Veitch's Rd., Papanui. -

Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan

Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan Incorporating s42A Recommendations 19 Feb 2012 Note: Grey text to be dealt with at a future hearing (This page is intentionally blank) This is the approved Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan, by the Canterbury Regional Council The Common Seal of the Canterbury Regional Council was fixed in the presence of: Bill Bayfield Chief Executive Canterbury Regional Council Dame Margaret Bazley Chair Canterbury Regional Council 24 Edward Street, Lincoln 75 Church Street P O Box 345 P O Box 550 Christchurch Timaru Phone (03) 365 3828 Phone (03) 688 9060 Fax (03) 365 3194 Fax (03) 688 9067 (This page is intentionally blank) Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan Incorporating s42A Recommendations KARANGA Haere mai rā Ngā maunga, ngā awa, ngā waka ki runga i te kaupapa whakahirahira nei Te tiakitanga o te whenua, o te wai ki uta ki tai Tuia te pakiaka o te rangi ki te whenua Tuia ngā aho te Tiriti Tuia i runga, Tuia i raro Tuia ngā herenga tangata Ka rongo te po, ka rongo te ao Tēnei mātou ngā Poupou o Rokohouia, ngā Hua o tōna whata-kai E mihi maioha atu nei ki a koutou o te rohe nei e Nau mai, haere mai, tauti mai ra e. 19 February 2013 i Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan Incorporating s42A Recommendations (This page is intentionally blank) ii 19 February 2013 Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan Incorporating s42A Recommendations TAUPARAPARA Wāhia te awa Puta i tua, Puta i waho Ko te pakiaka o te rākau o maire nuku, o maire raki, o maire o te māra whenua e -

RACE RESULTS Group 1 (Year 1 and 2) Girls Results

2015 Canterbury Primary and Intermediate School Championships Sunday 23 August 2015 RACE RESULTS Group 1 (Year 1 and 2) Girls Results BIB NAME SCHOOL RED BLUE AGG TIME PLACE NUMBER 15 Katie Chinn Somerfield School 31.22 28.74 59.96 1 7 Poppy Freeman Hororata School 31.66 31.21 62.87 2 16 Stella Valantine St Albans Primary School 45.47 42.39 87.86 3 14 Chlara Wieberneit Selwyn House School 47.50 41.98 89.48 4 9 Jasmine Ginnever Ohoka School 39.72 40.03 - DQ / OK 10 Gracie Haigh Ohoka School 39.88 36.84 - DQ / OK 19 Joy Chiles Springfield School 28.32 26.93 - DQ / OK Group 1 (Year 1 and 2) Boys Results BIB NAME SCHOOL RED BLUE AGG TIME PLACE NUMBER 40 Sam Moffatt Ohoka School 28.81 27.16 55.97 1 2 Gus Spillane Elmwood Normal School 34.84 31.26 66.10 2 12 Max Downes Redcliffs School 36.91 31.92 68.83 3 8 Baxter Olson North Loburn School 36.81 36.47 73.28 4 4 James Hunter Elmwood Normal School 62.44 55.05 117.49 5 3 Toby-withdrawn Brown Elmwood Normal School 0.00 0.00 - DQ / DQ 5 Jackson Douglas Fendalton School 37.47 33.88 - OK / DQ 6 Sam Hardy Glentunnel School 0.00 48.74 - DNF / OK 11 Ollie Tinkler Redcliffs School 46.41 47.31 - OK / DQ 13 Luca Cable Redcliffs School 38.00 35.31 - OK / DQ 17 Hayden Reed The Cathedral Grammar School 0.00 52.82 - FALL / OK 18 Baxter Bretherton West Eyreton School 0.00 47.72 - DQ / OK Well Done Everyone! Page | 1 2015 Canterbury Primary and Intermediate School Championships Sunday 23 August 2015 RACE RESULTS Group 2 (Year 3 and 4) Girls Results BIB NAME SCHOOL RED BLUE AGG TIME PLACE NUMBER 66 Henrietta Evatt -

Introduction Getting There Places to Fish Methods Regulations

3 .Cam River 10. Okana River (Little River) The Cam supports reasonable populations of brown trout in The Okana River contains populations of brown trout and can the one to four pound size range. Access is available at the provide good fishing, especially in spring. Public access is available Tuahiwi end of Bramleys Road, from Youngs Road which leads off to the lower reaches of the Okana through the gate on the right Introduction Lineside Road between Kaiapoi and Rangiora and from the Lower hand side of the road opposite the Little River Hotel. Christchurch City and its surrounds are blessed with a wealth of Camside Road bridge on the north-western side of Kaiapoi. places to fish for trout and salmon. While these may not always have the same catch rates as high country waters, they offer a 11. Lake Forsyth quick and convenient break from the stress of city life. These 4. Styx River Lake Forsyth fishes best in spring, especially if the lake has recently waters are also popular with visitors to Christchurch who do not Another small stream which fishes best in spring and autumn, been opened to the sea. One of the best places is where the Akaroa have the time to fish further afield. especially at dusk. The best access sites are off Spencerville Road, Highway first comes close to the lake just after the Birdlings Flat Lower Styx Road and Kainga Road. turn-off. Getting There 5. Kaiapoi River 12. Kaituna River All of the places described in this brochure lie within a forty The Kaiapoi River experiences good runs of salmon and is one of The area just above the confluence with Lake Ellesmere offers the five minute drive of Christchurch City. -

Oxford-Ohoka Community Board

From: Thea Kunkel To: Mailroom Mailbox Subject: Plan Change 7 to the LWRP Submission Date: Thursday, 12 September 2019 11:58:28 AM Good Day Please find attached the submission of the Oxford-Ohoka Community Board on the proposed Plan Change 7 to the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan and proposed Plan Change 2 to the Waimakariri River Regional Plan. Thea Kunkel | Governance Team Leader Governance Phone: 0800 965 468 (0800 WMK GOV) .~ WA I MA K AR I R I 0 ts,i waimakariri.govtnz . CUSl~ICT COUNCIL 6 September 2019 To: Environment Canterbury Subject: Plan Change 7 to the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan From: Oxford-Ohoka Community Board Doug Nicholl, Chairperson Contact: Thea Kunkel, Governance Team Leader [email protected] C/- Waimakariri District Council, Private Bag 1005, Rangiora 7440. ______________________________________________________________________________ The Oxford-Ohoka Community Board (the Board) welcomes the opportunity to comment on the proposed Plan Change 7 to the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan. Summary The Oxford-Ohoka Community Board endorses the Waimakariri District Council’s submission (attached) in the matter of the proposed Plan Change 7 to the Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan and proposed Plan Change 2 to the Waimakariri River Regional Plan. The Board however wishes to add the following: 8 Policies Nutrient management The Board is concerned about the reduction threshold for winter grazing from 10ha to 5ha. As Board members are of the opinion that farmers are not going to put their stock into a 5ha property or a number of 5ha properties, as this may jeopardise the health and welfare of their stock. -

Information Booklet

WEST EYRETON SCHOOL INFORMATION BOOKLET CONTENTS • Welcome Letter • Enrolment • The School and its Community • Staff, Board of Trustees and Friends of the School • General Information. • Academic • Other Programmes and Opportunities Available to Children • Health Issues. • Bus Behaviour Policy • West Eyreton Code of Conduct School Mission Statement A strong school TEAM striving for educational excellence. 1 West Eyreton School, Rangiora RD 5 Dear Parents and Caregivers, Welcome to West Eyreton School. We hope your association with the school will be a happy one. The facilities at West Eyreton are superb, and we are proud to continue a tradition of quality education for the children in this district. Country schools have a special, friendly nature, and close relationships develop between teachers, pupils and parents. At West Eyreton these bonds are fostered by the members of the Board of Trustees and the Friends of The School. These people, with the support of the community, organise fundraising and social events, and support the teachers in their efforts to provide enriching programmes for the children. You are very welcome to join these groups and we encourage you come along when social opportunities arise. They are a very successful way of meeting other families. This booklet should provide you with the necessary information about the running of the school. If there is anything further we can help you with, or at any time you are able to provide us with changed information in regards to your children, please do contact us. Thank you, Jillian Gallagher Principal. 2 ENROLMENT When you enrol your child at West Eyreton School you will receive a pack that contains forms and other information. -

Proposed Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan

Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan Volume 1 Prepared under the Resource Management Act 1991 August 2012 Everything is connected 2541 Land and Water Regional Plan Vol 1.indd 1 12/07/12 1:23 PM Cover photo The Rakaia River, one of the region’s braided rivers Credit: Nelson Boustead NIWA 2541 Land and Water Regional Plan Vol 1.indd 2 12/07/12 1:23 PM (this page is intentionally blank) Proposed Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan Errata The following minor errors were identified at a stage where they were unable to be included in the final printed version of the Proposed Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan. To ensure that content of the Proposed Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan is consistent with the Canterbury Regional Council’s intent, this notice should be read in conjunction with the Plan. The following corrections to the Proposed Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan have been identified: 1. Section 1.2.1, Page 1-3, second paragraph, second line – delete “as” and replace with “if”. 2. Rule 5.46, Page 5-13, Condition 3, line 1 – insert “and” after “hectare”. 3. Rule 5.96, Page 5-23, Condition 1, line 1 – delete “or diversion”; insert “activity” after “established” (this page is intentionally blank) Proposed Canterbury Land & Water Regional Plan - Volume 1 KARANGA Haere mai rā Ngā maunga, ngā awa, ngā waka ki runga i te kaupapa whakahirahira nei Te tiakitanga o te whenua, o te wai ki uta ki tai Tuia te pakiaka o te rangi ki te whenua Tuia ngā aho te Tiriti Tuia i runga, Tuia i raro Tuia ngā herenga tangata Ka rongo te po, ka rongo te ao Tēnei mātou ngā Poupou o Rokohouia, ngā Hua o tōna whata-kai E mihi maioha atu nei ki a koutou o te rohe nei e Nau mai, haere mai, tauti mai ra e. -

Draft Canterbury CMS 2013 Vol II: Maps

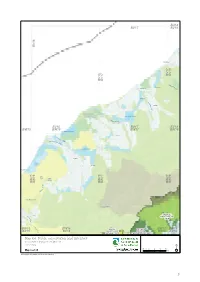

BU18 BV17 BV18 BV16 Donoghues BV17 BV18 BV16 BV17 M ik onu Fergusons i R iv Kakapotahi er Pukekura W a i ta h Waitaha a a R iv e r Lake Ianthe/Matahi W an g anui Rive r BV16 BV17 BV18 BW15 BW16 BW17 BW18 Saltwater Lagoon Herepo W ha ta ro a Ri aitangi ver W taon a R ive r Lake Rotokino Rotokino Ōkārito Lagoon Te Taho Ōkārito The Forks Lake Wahapo BW15 BW16 BW16 BW17 BW17 BW18 r e v i R to ri kā Ō Lake Mapourika Perth River Tatare HAKATERE W ai CONSERVATION h o R PARK i v e r C a l le r y BW15 R BW16 AORAKI TE KAHUI BW17 BW18 iv BX15 e BX16 MOUNT COOK KAUPEKA BX17 BX18 r NATIONAL PARK CONSERVATION PARK Map 6.6 Public conservation land inventory Conservation Management Strategy Canterbury 01 2 4 6 8 Map 6 of 24 Km Conservation unit data is current as of 21/12/2012 51 Public conservation land inventory Canterbury Map table 6.7 Conservation Conservation Unit Name Legal Status Conservation Legal Description Description Unit number Unit Area I35028 Adams Wilderness Area CAWL 7143.0 Wilderness Area - s.20 Conservation Act 1987 - J35001 Rangitata/Rakaia Head Waters Conservation Area CAST 53959.6 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 Priority ecosystem J35002 Rakaia Forest Conservation Area CAST 4891.6 Stewardship Area - s.25 Conservation Act 1987 Priority ecosystem J35007 Marginal Strip - Double Hill CAMSM 19.8 Moveable Marginal Strip - s.24(1) & (2) Conservation Act 1987 - J35009 Local Purpose Reserve Public Utility Lake Stream RALP 0.5 Local Purpose Reserve - s.23 Reserves Act 1977 - K34001 Central Southern Alps Wilberforce Conservation -

Boundaries, Sheet Numbers and Names of Nztopo50 Series 1:50

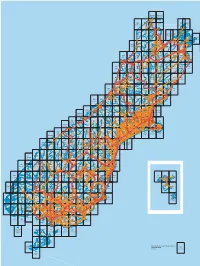

BM24ptBN24 BM25ptBN25 Cape Farewell Farewell Spit Puponga Seaford BN22 BN23 Mangarakau BN24 BN25 BN28 BN29ptBN28 Collingwood Kahurangi Point Paturau River Collingwood Totaranui Port Hardy Cape Stephens Rockville Onekaka Puramahoi Totaranui Waitapu Takaka Motupipi Kotinga Owhata East Takaka BP22 BP23 BP24 Uruwhenua BP25 BP26ptBP27 BP27 BP28 BP29 Marahau Heaphy Beach Gouland Downs Takaka Motueka Pepin Island Croisilles Hill Elaine Te Aumiti Endeavour Inlet Upper Kaiteriteri Takaka Bay (French Pass) Endeavour Riwaka Okiwi Inlet ptBQ30 Brooklyn Bay BP30 Lower Motueka Moutere Port Waitaria Motueka Bay Cape Koamaru Pangatotara Mariri Kenepuru Ngatimoti Kina Head Oparara Tasman Wakapuaka Hira Portage Pokororo Rai Harakeke Valley Karamea Anakiwa Thorpe Mapua Waikawa Kongahu Arapito Nelson HavelockLinkwater Stanley Picton BQ21ptBQ22 BQ22 BQ23 BQ24 Brook BQ25 BQ26 BQ27 BQ28 BQ29 Hope Stoke Kongahu Point Karamea Wangapeka Tapawera Mapua Nelson Rai Valley Havelock Koromiko Waikawa Tapawera Spring Grove Little Saddle Brightwater Para Wai-iti Okaramio Wanganui Wakefield Tadmor Tuamarina Motupiko Belgrove Rapaura Spring Creek Renwick Grovetown Tui Korere Woodbourne Golden Fairhall Seddonville Downs Blenhiem Hillersden Wairau Hector Atapo Valley BR20 BR21 BR22 BR23 BR24 BR25 BR26 BR27 BR28 BR29 Kikiwa Westport BirchfieldGranity Lyell Murchison Kawatiri Tophouse Mount Patriarch Waihopai Blenheim Seddon Seddon Waimangaroa Gowanbridge Lake Cape Grassmere Foulwind Westport Tophouse Sergeants Longford Rotoroa Hill Te Kuha Murchison Ward Tiroroa Berlins Inangahua -

Students Show Water Zone Committee How It's Done!

Enviroschools Canterbury February 2016 Chatterbox Students show water zone committee how it’s done! Students at our annual Enviro-leaders camp enjoyed getting into character for our mock water zone committee meeting ably chaired by a real committee chairperson, Clare McKay from the Waimakariri Water Zone Committee. Students gained insight into the complexities of water management and the different values and perspectives held by different groups. For many, this was the highlight of our camp with teachers impressed at how articulate these future leaders are in expressing their opinion. North Loburn students aka ‘Giga Energy Company’ confidently outlined the benefits of a fictitious hydro dam on the Glentui River as part of a mock water zone committee meeting 2016 Enviroleaders camp at Glentui Kia ora tātou, Thanks to the support of the Christchurch City Council’s Strengthening Communities Fund we are able to again offer facilitation support to CCC Enviroschools. We are excited about reconnecting with you all and are offering a free “Let’s get energised teacher hui on the 3rd March, Debbie from ECAN helps students to identify make sure you register early to secure Sean from Raptor Rescue explains how to your place! protect harrier hawks like Eva invertebrates in the Glentui River We farewell Hilary in the south and welcome Debbie Eddington into her role as Enviroschools Facilitator for South Canterbury. Debbie has a dual role delivering other ECAN education programmes and will know many of you already. We look forward to supporting you