Mining Amid Armed Conflict: Nonferrous Metals Mining in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Id Propuesta Clase Indicacion Comentarios Registro Pais

ALIANZA DEL PACÍFICO LISTADO DE TÉRMINOS Y REGIONALISMOS ARMONIZADOS DE PRODUCTOS Y SERVICIOS ID CLASE INDICACION COMENTARIOS REGISTRO PAIS PROPUESTA 1 2 achiote [pigmento] MEXICO 2 2 axiote [pigmento] MEXICO 3 5 agua de muicle [remedio medicinal] MEXICO 4 5 agua de muitle [remedio medicinal] MEXICO 5 5 té de muicle [remedio medicinal] MEXICO 6 5 té de muitle [remedio medicinal] MEXICO 7 15 ayoyote [instrumento musical] MEXICO 8 15 chapereque [instrumento musical] MEXICO 9 15 chirimía [instrumento musical] MEXICO 10 15 huéhuetl [instrumento musical] MEXICO 11 15 quinta huapanguera [instrumento musical] MEXICO 12 15 salterio [instrumento musical] MEXICO 13 15 teponaztli [instrumento musical] MEXICO 14 15 tochacatl [instrumento musical] MEXICO 15 15 toxacatl [instrumento musical] MEXICO 16 21 chashaku [pala de bambú para té] MEXICO 17 21 comal [utensilio de cocina] MEXICO 18 21 tamalera [olla de cocción] MEXICO 19 21 tejolote [utensilio de cocina] MEXICO 20 21 temolote [utensilio de cocina] MEXICO 21 21 tortilleros [recipientes] MEXICO 23 25 guayaberas [prenda de vestir] MEXICO 24 25 huaraches [sandalias] MEXICO 25 25 huipiles [vestimenta] MEXICO 26 25 jorongo [prenda de vestir] MEXICO 28 25 sarape [prenda de vestir] MEXICO ALIANZA DEL PACÍFICO LISTADO DE TÉRMINOS Y REGIONALISMOS ARMONIZADOS DE PRODUCTOS Y SERVICIOS 29 25 sombrero de charro MEXICO 30 27 petate [esteras de palma] MEXICO 31 29 acocil no vivo [crustáceo de agua dulce] MEXICO 32 29 aguachile [crustáceos preparados] MEXICO 33 29 aporreadillo [alimento a base de carne] MEXICO -

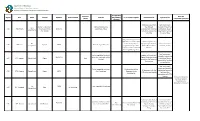

Region OTP Status Location Operator Products Average Sales

Department of Agriculture National Organic Agriculture Program Updates on the Status of Organic Trading Posts (OTPs) Average Sales Operation Other DA Region OTP Status Location Operator Date Launched Products (Day/Weekly/ No. of Farmer-suppliers Catchment Area Type of Buyers period Interventions/Support Monthly) Organic produce from local consumers/ Purok 5, Agro-prod. Heirloom/Native rice, the different inviduals, traders and non - CAR OTP Kalinga Compound, Tabuk PLGU/ FA vegetables, coffee municipalities of Kalinga institutional buyers operational City, Kalinga including Heirloom rice especially for heirloom and coffee rice and coffee Target beneficiary consists 80% of the total household All municipalities of For in the municipality as Apayao especially Luna, local consumers/ CAR OTP- Luna Apayao MLGU Fruits &, vegetables, rice Completion suppliers or buyers. This Pudtol, Flora and Sta. inviduals, traders may also include individuals Marcela from neighbouring areas. local consumers/ Fruits, vegetable, heirloom/ Lagawe as the capital of inviduals, traders and MLGU/ FA native rice, rootcrops, coffee, Ifugao, the project is seen CAR OTP- Lagawe Operational Ifugao daily institutional buyers livestock to cater to the farmers of especially for heirloom the province rice and coffee local consumers/ buyers and targeting Fruits, vegetable, heirloom Produce from all the All barangays with the institutional buyers for CAR OTP- Hingyon Operational Ifugao MLGU rice & rootcrops Barangays of the AOR of the municipality heirloom rice; Municipality partnership with OTP Lagawe Trainings/ Seminars/ Meetings; Market Development/ Promotions Assistance For PLGU Fruits, vegetable & rootcrops CAR OTP- Bangued Abra for launching Completion Organic produce from all local consumers/ vegetable, heirloom/ native the Municipalities such as inviduals, traders and PLGU/ FA Php 141 individuals (47 direct & CAR OTP- Bontoc Operational Mt. -

Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines – Online Appendix

ONLINE APPENDIX Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines Eugenia Go 28 February 2020 A.1. DATA 1. Maritime Trade by Origin and Destination The analysis is limited to a set of agricultural commodities corresponding to 101,159 monthly flows. About 5% of these exhibit highly improbable derived unit values suggesting encoding errors. More formally, provincial retail and farm gate prices are used as upper and lower bounds of unit values to check for outliers. In such cases, more weight is given to the volume record as advised by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), and values were adjusted according to the average unit price of the exports from the port of the nearest available month before and after the outlier observation. 2. Interprovince Land Trade Interprovince land trade flows were derived using Marketing Cost Structure Studies prepared by the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics for a number of products in selected years. These studies identify the main supply and destination provinces for certain commodities. The difference between production and consumption of a supply province is assumed to be the amount available for export to demand provinces. The derivation of imports of a demand province is straightforward when an importing province only has one source province. In cases where a demand province sources from multiple suppliers, such as the case of the National Capital Region (NCR), the supplying provinces are weighted according to the sample proportions in the survey. For example, NCR sources onions from Ilocos Norte, Pangasinan, and Nueva Ecija. Following the sample proportion of traders in each supply province, it is assumed that 26% of NCR imports came from Ilocos Norte, 34% from Pangasinan, and 39% from Nueva Ecija. -

Zambales Nickel Mining Impacts Sustainable Agriculture and Fisheries

ALYANSA TIGIL MINA Zambales nickel mining impacts sustainable agriculture and fisheries Who is the alleged victim(s) (individual(s), community, group, etc.): Farming and fishing communities in Sta Cruz Zambales Who is the alleged perpetrator(s) of the violation: Four large-scale mining companies (extracting nickel) are blamed for the irreversible environmental degradation and destruction in the town of Sta. Cruz, namely: Zambales Diversified Metals Corp. Benguet Corp. Nickel Mines Inc. Eramin Minerals Inc. LNL Archipelago Minerals Inc The nickel mining operations result in water pollution due to nickel laterite. This has seeped in the irrigated water sources and reached 30-nautical miles offshore, affecting both agriculture and fishery sectors. Date, place and detailed description of the circumstances of the incident(s) or the violation: Sta. Cruz is a 1st class municipality with rich arable land that is conjusive for farming. The whole province of Zambales owes its title as “home of the best carabao mango of the world” to its rich land. To date, because of the nickel mining: Sta. Cruz, Zambales is losing 8,000 tons of palay production annually worth Php 200-million (US$5M). It has and estimated loss of Php 20-million (US$ 0.5M) from fish production in three major rivers and at least Php 30-million (or US$0.75M) (each hectare earning a net of Php 300,000.00 annually) loss from fish production in at least 100-hectares of fishpond. As an effect of the nickel laterite reaching offshore, there was also a declined in catch in deep sea fishing. There is also a radical reduction in the production of the best and sweetest carabao mango. -

Volume Xxiii

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME XXIII NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1925 Editor CLARK WISSLER FOREWORD Louis ROBERT SULLIVAN Since this volume is largely the work of the late Louis Robert Sulli- van, a biographical sketch of this able anthropologist, will seem a fitting foreword. Louis Robert Sullivan was born at Houlton, Maine, May 21, 1892. He was educated in the public schools of Houlton and was graduated from Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in 1914. During the following academic year he taught in a high school and on November 24, 1915, he married Bessie Pearl Pathers of Lewiston, Maine. He entered Brown University as a graduate student and was assistant in zoology under Professor H. E. Walters, and in 1916 received the degree of master of arts. From Brown University Mr. Sullivan came to the American Mu- seum of Natural History, as assistant in physical anthropology, and during the first years of his connection with the Museum he laid the foundations for his future work in human biology, by training in general anatomy with Doctor William K. Gregory and Professor George S. Huntington and in general anthropology with Professor Franz Boas. From the very beginning, he showed an aptitude for research and he had not been long at the Museum ere he had published several important papers. These activities were interrupted by our entrance into the World War. Mr. Sullivan was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Section of Anthropology, Surgeon-General's Office in 1918, and while on duty at headquarters asisted in the compilation of the reports on Defects found in Drafted Men and Army Anthropology. -

Philippines Broad Listening Report

LOCAL SYSTEMS PRACTICE (LSP) ACTIVITY LOCAL WORKS PHILIPPINES | BROAD LISTENING TOUR ANALYSIS August 7, 2018 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by the Local Systems Practice consortium. USAID/Philippines Local Works Broad Listening Analysis Prepared by: Rahul Oka, AVSI Jenna White, LINC Rieti Gengo, AVSI Patrick Sommerville, LINC Front cover: Listening Tour in Sto. Tomas. Acknowledgements: The author(s) would like to acknowledge all of our LSP consortium partners for their input throughout the process, participants who took the time to participate in the Broad Listening Tour activities. These contributions are crucial for advancing our mutual efforts towards improved local development in the Philippines. About Local Systems Practice: Local Systems Practice is a USAID-funded activity that directly assists multiple Missions, partners, and constituents to design and adaptively manage systems-based programs in complex environments. The concept has been designed to aid Missions and partners to overcome four specific challenges to effective Local Systems Practice through: a) Listening; b) Engagement; c) Discovery; and d) Adaptation. The Theory of Change underpinning the activity asserts that the application of systems tools to complex local challenges at multiple intervals throughout the program cycle will enhance the sustainability of programming, resulting in better-informed, measurable interventions that complement and reinforce the systems they seek to strengthen. The LSP team is composed of both development practitioners and research institutions to most effectively explore and implement systems thinking approaches with Missions, local partners and other local stakeholders. The activity is led by LINC LLC with five sub-implementers: ANSER, the University of Notre Dame, AVSI, the University of Missouri, and Practical Action. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Downloads/SR324-Atural%20 Disasters%20As%20Threats%20To%20 Peace.Pdf

The Bedan Research Journal (BERJ) publishes empirical, theoretical, and policy-oriented researches on various field of studies such as arts, business, economics, humanities, health, law, management, politics, psychology, sociology, theology, and technology for the advancement of knowledge and promote the common good of humanity and society towards a sustainable future. BERJ is a double-blind peer-reviewed multidisciplinary international journal published once a year, in April, both online and printed versions. Copyright © 2020 by San Beda University All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without written permission from the copyright owner ISSN: 1656-4049 Published by San Beda University 638 Mendiola St., San Miguel, Manila, Philippines Tel No.: 735-6011 local 1384 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sanbeda.edu.ph Editorial Board Divina M. Edralin Editor-in-Chief San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Nomar M. Alviar Managing Editor San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Ricky C. Salapong Editorial Assistant San Beda University, Manila, Philippines International Advisory Board Oscar G. Bulaong, Jr. Ateneo Graduate School of Business, Makati City, Philippines Christian Bryan S. Bustamante San Beda University, Manila, Philippines Li Choy Chong University of St. Gallen, Switzerland Maria Luisa Chua Delayco Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Brian C. Gozun De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Raymund B. Habaradas De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines Ricardo A. Lim Asian Institute of Management, Makati City, Philippines Aloysius Ma. A. Maranan, OSB San Beda University, Manila, Philippines John A. -

Important Traits of the Basilan Chicken: an Indigenous Chicken of Mindanao, Philippines

Important Traits of the Basilan Chicken: an Indigenous Chicken of Mindanao, Philippines Henry Rivero1, Leo Johncel Sancebutche2, Mary Grace Tambis3, Iris Neville Bulay-Og4, Dorothy Liz June Baay5, Ian Carlmichael Perez6, Jenissi Ederango7, and Neil Mar Castro8 MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology, Philippines [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], 7 8 [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - This paper introduces the Basilan chicken, as assumed ecotype of the Asil of Pakistan and India, and widely distributed throughout Southeast Asia and in Mindanao, as an important breed for future consideration for livestock studies. The biological characteristics of the indigenous chicken have been noted and compared among four geographically distant groups within a small regional setting. A collection of representative chickens putatively of the same Basilan stocks from four provinces was established. The question whether the pure Basilan stock distributed in the entire island of Mindanao originated from the Basilan Island was answered by cluster analysis of the ten external phenotypic characters. The relatedness based on presence and absence of the tested phenotypes of the Basilan chickens from four geographically distant provinces of Surigao (in Eastern Mindanao), Agusan (in the CARAGA region), Lanao (in Northern Mindanao), and Basilan (in Western Mindanao), was examined for comparison including the hepatic, gonad, and hematologic -

DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” As of 22 December 2020, 6PM

DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” as of 22 December 2020, 6PM Situation Overview On 18 December 2020, Tropical Depression “VICKY” entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) and made its first landfall in the municipality of Banganga, Davao Oriental at around 2PM. On 19 December 2020, Tropical Depression “VICKY” made another landfall in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan and remained a tropical depression while exiting the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) on 20 December 2020. Source: DOST-PAGASA Severe Weather Bulletin I. Status of Affected Families / Persons A total of 31,408 families or 130,855 persons were affected in 290 barangays in Regions VII, VIII, XI and Caraga (see Table 1). Table 1. Number of Affected Families / Persons NUMBER OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY Barangays Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 290 31,408 130,855 REGION VII 32 618 2,510 Bohol 3 15 60 Candijay 3 15 60 Cebu 15 441 1,812 Argao 1 15 45 Boljoon 2 13 44 Compostela 2 54 221 Dalaguete 1 2 8 Danao City 1 150 600 Dumanjug 1 20 140 Lapu-Lapu City (Opon) 4 163 662 Sibonga 3 24 92 Negros Oriental 14 162 638 Bais City 3 33 125 Dumaguete City (capital) 6 92 365 City of Tanjay 5 37 148 REGION VIII 2 12 38 Leyte 2 12 38 MacArthur 1 10 34 Mahaplag 1 2 4 REGION XI 22 608 2,818 Davao de Oro 13 294 1,268 Compostela 2 10 37 Mawab 1 7 20 Monkayo 3 72 360 Montevista 1 13 65 Nabunturan (capital) 4 152 546 Pantukan 2 40 240 Davao del Norte 8 310 1,530 Asuncion (Saug) 6 238 1,180 Kapalong 1 12 50 New Corella 1 60 300 Davao Oriental 1 4 20 Cateel 1 4 20 CARAGA 234 30,170 125,489 Page 1 of 9 | DSWD DROMIC Report #5 on Tropical Depression “VICKY” as of 22 December 2020, 6PM NUMBER OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY Barangays Families Persons Agusan del Norte 30 1,443 6,525 Butuan City (capital) 16 852 4,066 City of Cabadbaran 9 462 2,007 Jabonga 2 38 119 Las Nieves 1 10 50 Remedios T. -

PHL-OCHA-R11 Profile-A3

Philippines: Region XI (Davao) Profile Region XI (Davao) is located in the southeastern POPULATION POVERTY portion of the island of Mindanao surrounding the Davao Gulf. Source: PSA 2010 Census Source: PSA 2016 It is bordered to the north by the provinces of Surigao del Sur, 5 6 43 1,162 Region XI population Region XI households 2.39M Poverty incidence among population (%) Agusan del Sur, and Bukidnon, on the east by the Philippine PROVINCES CITIES MUNICIPALITIES BARANGAYS Sea, and on the west by the Central Mindanao provinces. 4.89 1.18 48.9% 60% million million 40% 30.7% Female 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 9 4 30.6% 31.4% + 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 9 4 - Population statistics trend - - - - - - - - - - 20% - - 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 6 6 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 22.0% Male 0 2006 2009 2012 2015 51.1% 4.89M 4.47M 2015 Census 2010 Census 2.50M % Poverty incidence 0 - 14 15 - 26 27 - 39 40 - 56 57 - 84 DAVAO DEL NORTE NATURAL DISASTERS HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Nabunturan 4,300 Source: OCD/NDRRMC Conditional cash transfer Source: DSWD 117 Number of disaster beneficiaries (children) incidents per year 562,200 272,024 Tagum Affected population 451,700 31 (in thousands) 21 21 24 427,500 219,637 Notable incidents Typhoon 209,688 COMPOSTELA 300,500 Girls Flooding 290,158 232,085 119,200 VALLEY 147,666 248 No affected population 217,764 107,200 2 94 27 due to tropical cyclones in 2015 and 2016 DAVAO ORIENTAL 152,871 Boys Davao City 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 Mati DAVAO DEL SUR NUTRITION WATER AND SANITATION HEALTH Source: FNRI 2012 Source: PSA 2010 -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love.