Organizing the Orals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

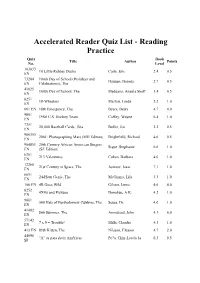

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Objects in Tom Stoppard's Arcadia

Cercles 22 (2012) ANIMAL, VEGETABLE OR MINERAL? OBJECTS IN TOM STOPPARD’S ARCADIA SUSAN BLATTÈS Université Stendhal—Grenoble 3 The simplicity of the single set in Arcadia1 with its rather austere furniture, bare floor and uncurtained windows has been pointed out by critics, notably in comparison with some of Stoppard’s earlier work. This relatively timeless set provides, on one level, an unchanging backdrop for the play’s multiple complexities in terms of plot, ideas and temporal structure. However we should not conclude that the set plays a secondary role in the play since the mysteries at the centre of the plot can only be solved here and with this particular group of characters. Furthermore, I would like to suggest that the on-stage objects play a similarly vital role by gradually transforming our first impressions and contributing to the multi-layered meaning of the play. In his study on the theatre from a phenomenological perspective, Bert O. States writes: “Theater is the medium, par excellence, that consumes the real in its realest forms […] Its permanent spectacle is the parade of objects and processes in transit from environment to imagery” [STATES 1985 : 40]. This paper will look at some of the parading or paraded objects in Arcadia. The objects are many and various, as can be seen in the list provided in the Samuel French acting edition (along with lists of lighting and sound effects). We will see that there are not only many different objects, but also that each object can be called upon to assume different functions at different moments, hence the rather playful question in the title of this paper (an allusion to the popular game “Twenty Questions” in which the identity of an object has to be guessed), suggesting we consider the objects as a kind of challenge to the spectator, who is set the task of identifying and interpreting them. -

Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep March 2003 3-28-2003 Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: March 28, 2003" (2003). March. 14. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2003_mar/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2003 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in March by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Thll the troth March28,2003 + FRIDAY and don't be afraid. • VO LUME 87 . NUMBER 123 THE DA ILYEASTERN NEWS . COM THE DAILY Four for 400 Eastern baseball team has four chances this weekend to earn head coach Jim EASTERN NEWS <:rlh....,,t n his 400th career Student fees may be hiked • Fees may raise $70 next semester By Avian Carrasquillo STUDENT GOVERNMENT ED ITOR If approved students can expect to pay an extra $70.55 in fees per semester. The Student Senate Thition and Fee Review Committee met Thursday to make its final vote on student fees for next year. Following the committee's approval, the fee proposals must be approved by the Student Senate, vice president for student affairs, the President's Council and Eastern's Board of Trustees. The largest increase of the fees will come in the network fee, which will increase to $48 per semester to fund a 10-year network improvement project. The project, which could break ground as early as this summer would upgrade the campus infra structure for network upgrades, which will Tom Akers, head coach of Eastern's track and field team, watches high jumpers during practice Thursday afternoon. -

1 Introduction It Is My Goal in This Paper to Offer a Strategy For

Three Archetypes for the Clarification Christopher Yorke Of Utopian Theorizing University of Glasgow Introduction It is my goal in this paper to offer a strategy for translating universal statements about utopia into particular statements. This is accomplished by drawing out their implicit, temporally embedded, points of reference. Universal statements of the kind I find troublesome are those of the form ‘Utopia is x’, where ‘x’ can be anything from ‘the receding horizon’ to ‘the nation of the virtuous’. To such statements, I want to put the questions: ‘Which utopias?’; ‘In what sense?’; and ‘When was that, is that, or will that be, the case for utopias?’ Through an exploration of these lines of questioning, I arrive at three archetypes of utopian theorizing which serve to provide the answers: namely, utopian historicism, utopian presentism, and utopian futurism. The employment of these archetypes temporally grounds statements about utopia in the past, present, or future, and thus forces discussion of discrete particulars instead of abstract universals with no meaningful referents. Given the vague manner in which the term ‘utopia’ is employed in discourse—whether academic or non-academic—confusion frequently, and rightly, ensues. There are various possible sources for this confusion, the first of which is the sheer volume and wide variety of socio-political schemes that have been regarded as utopian, by utopian theorists, historians, or authors of fiction. Bibliographers of utopian literature (such as Lyman Tower Sargent) face the onerous task of sorting out those visions of other worlds that belong in the utopian canon from those that do not. However, utopian bibliographies generally err on the side of inclusiveness, and a sufficient range and number of utopias remain in the realm of discourse to make the practice of distinguishing a utopia from a non-utopia (or even a dystopia) challenging at best and baffling at worst. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture PLANTAE, ANIMALIA, FUNGI: TRANSFORMATIONS OF NATURAL HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN ART A Dissertation in Art History by Alissa Walls Mazow © 2009 Alissa Walls Mazow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The Dissertation of Alissa Walls Mazow was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Richard M. Doyle Professor of English, Science, Technology and Society, and Information Science and Technology Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the ways that five contemporary artists—Mark Dion (b. 1961), Fred Tomaselli (b. 1956), Walton Ford (b. 1960), Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and Cy Twombly (b. 1928)—have adopted the visual traditions and theoretical formulations of historical natural history to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture” and begin new dialogues about emerging paradigms, wherein plants, animals and fungi engage in ecologically-conscious dialogues. Using motifs such as curiosity cabinets and systems of taxonomy, these artists demonstrate a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history. For these practitioners natural history operates within the realm of history, memory and mythology, inspiring them to make works that examine a scientific paradigm long thought to be obsolete. This study, which itself takes on the form of a curiosity cabinet, identifies three points of consonance among these artists. -

History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats Timothy Ruppert

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2008 "Is Not the Past All Shadow?": History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats Timothy Ruppert Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ruppert, T. (2008). "Is Not the Past All Shadow?": History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1132 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Timothy Ruppert March 2008 Copyright by Timothy Ruppert 2008 “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS By Timothy Ruppert Approved March 25, 2008 _____________________________ _____________________________ Daniel P. Watkins, Ph.D. Jean E. Hunter , Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of History (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) _____________________________ _____________________________ Albert C. Labriola, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (Committee Member) (Chair, Department of English) _____________________________ Albert C. Labriola, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of English iii ABSTRACT “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS By Timothy Ruppert March 2008 Dissertation Supervised by Professor Daniel P. -

Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature

Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature Text: Thomas Le Blanc Research: Svenja Partheil and Verena Knorpp Translation: Klaudia Seibel Phantastische Bibliothek Wetzlar Special thanks to the authors Karl-Ulrich Burgdorf and Friedhelm Schneidewind for the kind permission to publish and translate their two short stories Imprint Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature German original: Vol. 24 of the Hessen-Nanotech series by the Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Compiled and written by Thomas Le Blanc Svenja Partheil, Verena Knorpp (research) Phantastische Bibliothek Wetzlar Turmstrasse 20 35578 Wetzlar, Germany Edited by Sebastian Hummel, Ulrike Niedner-Kalthoff (Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen) Dr. David Eckensberger, Nicole Holderbaum (Hessen Trade & Invest GmbH, Hessen-Nanotech) Editor For NANORA, the Nano Regions Alliance: Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring 75 65185 Wiesbaden, Germany Phone: +49 (0) 611 815 2471 Fax: +49 (0) 611 815 49 2471 www.wirtschaft.hessen.de The editor is not responsible for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of this information nor for observing the individual rights of third parties. The views and opinions rendered herein do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editor. © Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring 75 65185 Wiesbaden, Germany wirtschaft.hessen.de All rights reserved. No part of this brochure may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

Promoting Paradise: Utopianism And

New Zealand Journal of History, 42, 1 (2008) Promoting Paradise UTOPIANISM AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NEW ZEALAND, 1870–1930 A NUMBER OF COMMENTATORS have identified a correlation between aspects of utopianism and New Zealand’s past. Miles Fairburn, for example, has emphasized the power of an arcadian myth in nineteenth-century New Zealand.1 James Belich entitled the second volume of his history of New Zealand Paradise Reforged.2 And Lucy Sargisson and Lyman Tower Sargent’s work on intentional communities (or communes) argued that New Zealand ‘has a special place in the history of utopianism’.3 As Sargisson and Sargent note, though, there has not been any extended discussion of the association between utopianism and New Zealand’s national identity. Fairburn’s work comes closest, but the ‘governing category’ of his landmark study was ‘the colony’s social organisation’ rather than arcadian myths.4 Furthermore, Fairburn’s work stops in the 1890s, ignores ideal visions of cities and towns, disregards utopian fiction, and does not take into account ‘race’ and politics and the impact which these had on images of arcadia. While ‘race’ and politics are central to Belich’s work his study remains first and foremost a general history. The use of the descriptor ‘paradise’, like his term ‘recolonization’ (which is used to signify New Zealand’s apparent return to the British imperial fold), works primarily as ‘a heuristic device … to give pattern’.5 Belich also overlooks utopian and science fiction (SF) literature, focuses on the printed word and skips over ‘booster’ sources, namely those civic and commercial publications produced locally to promote settlement and investment. -

Composting Arcadia Stories from Pākehā Women “Of the Land” in Wairarapa, Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca L Ream

Composting arcadia Stories from Pākehā women “of the land” in Wairarapa, Aotearoa New Zealand by Rebecca L Ream A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2020) Abstract I suggest that this thesis is a compost pile from Wairarapa that slowly turns over harmful but potentially fertile tales of arcadia. I narrate this thesis drawing on the fleshly stories of ten Pākehā (colonial settler) women “of the land’ and the ethico-onto-epistemology of Donna Haraway’s compost making. Composting is Haraway’s (2016) latest feminist call to trouble and queer the self-contained secular humanism of Western1 modernity. Uprooting the Western separation of ‘nature’ from culture, Haraway’s philosophy provides an earthly foundation in which to compost arcadia. Arcadia is an antique ‘nature’ myth that has been enmeshed in the process of Western world making from Classical Greece to the European ‘Age of Discovery’. Arcadia was used by the British to colonise Aotearoa New Zealand2 in the nineteenth century. As a Pākehā, I have been compelled to explore this myth because of the way it has seeped into transcendent understandings of land for descendants of colonial settlers like myself. Commonly known as a rural paradise, arcadia was a strategy for ‘normalising’ and ‘naturalising’ European occupancy in New Zealand (Evans, 2007; Fairburn, 1989). British arcadianism arrived on the shores of New Zealand, Victorian and romantic. Therefore, in this thesis I posit that through both settler and romantic ideals, Pākehā continue to use arcadianism to relate to land. -

Over 150 Show up to Demand MTA Board Oppose Payroll

WEEK OF MARCH 9, 2009 www.hvbizjournal.com Published Weekly Volume 19, Number 10 Single Copy 75¢ is LIVE! Over 150 show up to demand MTA Banking, Finance and The Stimulus Pages 15-24 Board oppose payroll tax Hudson Valley BUSINESS JOURNAL March 9, 2009 -25 BY DYLAN SKRILOFF Inside story A proposed 0.333% payroll tax on business- As we begin this quadricentennial year of celebrating Henry Hudson’s exploration of the Hudson River, Samuel de Champlain’s exploration of Lake Champlain and the bicentennial of Robert Fulton’s successful steamboat run on the Hudson, we thought it might be fun to take a look at the economic history behind these events. The series is a synopsis of a forthcoming book I’m working on on the subject. PARTSEVEN es in a twelve-county region to help the Railroads and the growth of New York BY DEBBIE KWIATOSKI Corning, a wealthy Albany industrialist Watch out for mold According to the 1820 census, there built the who first line.. In 1831, his com- Key Dates for Railroad were 1.4 million people living in New pany had the first regularly scheduled rail Development in Page 26 York State. By 1900, there were 11 mil- service, running 11 miles between Albany New York State lion. The biggest contributing factor to the and Schenectady on the Mohawk and state’s phenomenal growth spurt in the Hudson Rail Road. The line linked the 1831 – First successful railroad line 19th century was, perhaps, a similar Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, making it Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) bridge begins regular service between Albany growth spurt in the role played by an convenient and even more cost-effective and Schenectady invention that was a mere curiosity in to move goods between the Midwest and 1850 – First Telegraph line set along 1830: The steam locomotive. -

The Eden Project – Gardens, Utopia and Heterotopia

Heterotopian Studies The Eden Project – gardens, utopia and heterotopia To reference this essay: Johnson, P. (2012) ‘The Eden Project – gardens, utopia and heterotopia’ Heterotopian Studies [http://www.heterotopiastudies.com] Gardens and utopia Utopias have ‘frequently invoked the special and resonant spaces of gardens, just as gardens have often been utopian in impulse, design and meaning’ (Hunt, 1987: 114): The garden provides an image of the world, a space of simulation for paradise-like conditions, a place of otherness where dreams are realised in an expression of a better world. (Meyer, 2003: 131) The garden features strongly in Thomas More’s original account of utopia. The conversations that form the basis of the book take place in a garden in Antwerp (1965: 17); the narrative suggests that the founder of utopia must have had a ‘special interest’ in gardening; and the inhabitants of utopia are said to be particularly fond of their gardens (53). Bloch goes so far as to suggest that in More’s utopia, ‘life is a garden’ (1986a: 475). Mosser and Teyssot assert that ‘nostalgia for the Garden of Eden has provided garden designers throughout history with a model of perfection to aspire to’ (1990: 12). Elsewhere, Mosser claims that garden enthusiasts seem ‘devoted to creating the impossible’ (1990: 278). Bauman asserts that gardeners ‘tend to be the most ardent producers of utopias’ (2005: 4). A recent exhibition at the National Art Museum of China (2008) entitled ‘Garden Utopia’ articulates the traditional perspective of a Chinese garden as a space for ‘contemplation, a borderland between reality and fantasy to escape the trappings of the modern world and reconnect humanity with nature’.