'Court' of Last Resort a Study of Constitutional Clemency for Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

Current Affairs Monthly Capsule and Quiz May 2018

Current Affairs Monthly Capsule and Quiz May 2018 1 WiFiStudy.com brief and impressive handing over of troops ceremony. Lt Col Irwan Ibrahim, Commanding officer World Immunization Week: 24 April- 30 April of the 1st Royal Ranger Regiment of 2018 Malaysian Army welcomed the Indian World Immunization contingent and wished the Indian and Week 2018 is celebrated Malaysian troops for a successful and from April 24 to April 30. mutually beneficial joint exercise. Immunization is First phase of the two week long joint considered to be military exercise begin with the formal one of the most cost-effective and successful handing over of the Regimental Flag to the plans in the health industry. Malaysian Army signifying merging of the World Immunization Week aims at two contingents under one Commander. highlighting the collective effort which is needed to ensure that every person gets protection from diseases which can be World Asthma Day 2018: 1 May World Asthma Day is an annual event organized by prevented from vaccines. the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) to Theme for the year 2018 is “Protected improve asthma awareness and care around the Together, Vaccines Work”. world. World Asthma Day takes place on the first International Buddhist Conference concluded in Tuesday of May. First World Asthma Day Lumbini was held in 1998. International Buddhist Conference concluded in The theme for the year 2018 is “Never too Lumbini, Nepal, which is the birth place of Gautama early, never too late. It’s always the right Buddha. time to address airways disease”. It was organised as part of 2562nd Buddha Jayanti celebrations. -

IJSA December 2008

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS NOVEMBER 2008 Volume 18 No. 2 Published By: The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246 University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, Alberta CANADA ISSN 1481-5435 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.yahoogroups.com/group/IntJSA INTERNATIONAL JOURNA L OF SIKH AFFAIRS Editorial Board Founded by: Dr Harjinder Singh Dilgeer Editorial Advisors Dr S S Dhami, MD Dr B S Samagh Dr Surjit Singh Prof Gurtej Singh, IAS Dr R S Dhadli New York, USA Ottawa, CANADA Williamsville, NY Chandigarh Troy, USA J S Dhillon “Arshi” M S Randhawa Usman Khalid Dr Sukhjit Kaur Gill Gurmit Singh Khalsa MALAYSIA Ft. Lauderdale, FL Editor, LISA Journal Chandigarh AUSTRALIA Dr Sukhpreet Singh Udhoke PUNJAB Managing Editor and Acting Editor in Chief: Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246, University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA E-mail:<[email protected]> NOTE: Views presented by the authors in their contributions in the journal are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor in Chief, the Editorial Advisors, or the publisher. SUBCRIPTION: US$75.00 per anum plus 6% GST plus postage and handling (by surface mail) for institutions and multiple users. Personal copies: US$25.00 plus &% GST plus postage and handling (surface mail). Orders for the current and forthcoming issues may be placed with the Sikh Educational Trust, Box 60246, Univ of AB Postal Outlet, EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA. E-mail: [email protected] The Sikh Leaders, Freedom Fighters and Intellectuals To bring an end to tyranny it is a must to punish the terrorist -Baba (General) Banda Singh Bahadar Sikhs have only two options: slavery of the Hindus or struggle for their lost sovereignty and freedom -Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS, MP, MLA and National Professor of Sikhism I am not afraid of physical death; moral death is death in reality Saint-soldier Jarnail Singh Khalsa Martyrdom is our orn a m e n t -Bhai Awtar Singh Brahma (General) We do not fear the terrorist Hindu regime. -

INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE V O L U M E X X V

Price Re. 1/- INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE v o l u m e X X V. No. 3 May–June 2011 diverse: Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh, Gilgit-Baltistan A Troubled Eden and what is now Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. It is BOOK RELEASE: A Tangled Web: in this genesis, perhaps, that the seeds of the current Jammu & Kashmir, IIC Quarterly, co-published with unrest lie. And the key to peace in this volatile HarperCollins India Limited, 2011 region is in an understanding of this diversity. Edited by Ira Pande The essays here familiarize the reader with the Released by Dr. Karan Singh, May 5 conflicting views on history, politics and autonomy pertaining to the region, and examine the various The launch of the special issue of the IIC Quarterly political, cultural, economic and social issues at play. is an annual rite when its double Winter-Spring issue Also included are features that voice the concerns of is released before a distinguished gathering. Speaking ordinary men and women who have borne the brunt Launch of IIC Quarterly, A Tangled Web: Jammu & Kashmir on the occasion, Dr. Karan Singh, Chairman of the of decades of unrest; as well as commentaries on the Editorial Board, gave an emotional account of his beauty, art and food typical of the area; and photo personal attachment to this troubled area and set features that capture its ethereal and unique essence. the tone for a discussion by Shri Salman Haidar and The essays, by a wide selection of analysts and Madhu Kishwar as they traced the journey of this politicians, academics and artists, try to make jinxed paradise. -

Starred Articles

GKCA Update st th 1 to 30 June Starred Articles 05 CII announces 10-point plan for economic revival June Economy > GDP India The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) voiced its concern over the stagnant state of the Indian economy and in a bid to rescue her, has unveiled a 10-point agenda for its revival. The remedies include fast-tracking the implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST) and easing of FDI (foreign direct investment) regulations in aviation and other sectors. Addressing a press conference on 5th June 2012, CII President, Adi B. Godrej, said that the primary concern for the nation was its GDP growth rate which was a mere 5.37 per cent in the last quarter was lowest in nine years. Some of the important reform to improve GDP growth as suggested by him are - early introduction of GST, the Government and the RBI inclusion of a strong monetary stimulus, correcting the current account deficit by encouraging exports and containing imports, arresting rupee slide, reducing subsidies, implementing financial sector reforms and removing bottlenecks in infrastructure growth. 06 Venus Transits between Sun and Earth June World > Space Planet Venus passed directly between the Sun and Earth on 6 June 2012, an astronomical rarity that sky watchers were eager to witness. Such a transit will not occur until 2117. The Transit of Venus, as it is called, appeared like a small dot on the Sun's elaborate circumference. This transit, which bookended a 2004-2012 pair, began at 6:09 p.m. EDT (2209 GMT) and lasted for six hours and 40 minutes. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS

Sabrang Elections 2004: FACTSHEETS Scamnama: The unending saga of NDA’s scams – Armsgate, Coffinsgate, Customscam, Stockscam, Telecom, Pumpscam… Scandalsheet 2: Armsgate (Tehelka) __________________________________________________________________ ‘Zero tolerance of corruption’. -- Prime Minister Vajpayee’s call to the nation On October 16, 1999. __________________________________________________________________ March 13, 2001: · Tehelka.com breaks a story that stuns the nation and the world. Tehelka investigators had captured on spy camera the president of the BJP, Bangaru Laxman, the Samata Party president, Jaya Jaitly (described as the ‘Second Defence Minister’ by one of the middlemen interviewed on videotape), and several top Defence Ministry officials accepting money, or showing willingness to accept money for defence deals. · This they had managed to do through a sting operation named Operation West End, posing as representatives of a fictitious UK based arms manufacturing firm. · Tehelka claims it paid out Rs. 10,80,000 in bribes to a cast of 34 characters. · Among the shots forming part of the four-and-a-half hour documentary are those of Bangaru Laxman accepting one lakh and asking for the promised five lakhs in dollars! He did not deny accepting the money. Bangaru Laxman resigns as BJP president. · Even before screening of the tapes at a press conference at a leading hotel here was over, the issue rocked both Houses of Parliament forcing their adjournment with the opposition demanding an immediate government statement on the issue. · The Union government says it is prepared for an inquiry into the tehelka.com expose of the alleged involvement of top politicians and government officials in corrupt defence deals. At an emergency Union Cabinet meeting George Fernandes reportedly offers to resign but the offer is rejected by the Prime Minister. -

Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr

Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate All India Federation of Tax Practitioners Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate – Remembering the Legend - A Tribute Regd. Office : 215, Rewa Chambers, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai - 400 020. All India Federation Tel.: 022-2200 6342 / 63 / 4970 6343 of Tax Practitioners E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.aiftponline.org Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate Centenary Celebration of Padma Vibhushan Late Dr. N. A. Palkhivala Senior Advocate – Remembering the Legend - A Tribute Regd. Office : 215, Rewa Chambers, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai - 400 020. All India Federation Tel.: 022-2200 6342 / 63 / 4970 6343 of Tax Practitioners E-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.aiftponline.org | i | | Palkhivala – Tribute | © All India Federation of Tax Practitioners 1st Edition : January 2021 DISCLAIMER Disclaimer The contents of this publication are solely for educational purposes. It does not constitute professional advice or formal documentation. While due care and sincere efforts has been made in preparing this digest to avoid errors or omissions, the existence of mistakes and omissions not ruled out. Any mistake. error or discrepancy may be brought to the notice. Neither the members of the research team, editorial team nor the All India Federation of Tax Practitioners (AIFTP) accepts any liabilities. No part of this publication should be distributed or copied for commercial use, without express written permission from the AIFTP. All disputes are subject to Mumbai Jurisdiction. Published by Dr. K. Shivaram, Senior Advocate for All India Federation of Tax Practitioners, 215, Rewa Chambers, 2nd Floor, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai–400 020. -

From Sampurna Swaraj to Sampurna Azadi: the Unfinished Agenda

From Sampurna Swaraj NANl A. PALKHIVALA to Sampurna Azadi: MEMORIAL TRUST The Unfinished Agenda We hardly need to introduce you to the life and work of the late Nani A. Palkhivala. He was a legend in his lifetime. An outstanding jurist, an authority on Constitutional and Taxation laws, the late Nani Palkhivala’s contribution to these fields and to several others such as economics, diplomacy and philosophy, C. K. Prahalad are of lasting value for the country. He was a passionate democrat and patriot, and above all, he Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Professor, was a great human being. Ross School of Business, The University of Michigan, USA Friends and admirers of Nani Palkhivala decided to perpetuate his memory through the creation of a public charitable trust to promote and foster the causes and concerns that were close to his heart. Therefore, the Nani A. Palkhivala Memorial Trust was set up in 2004. The Seventh Nani A. Palkhivala The main objects of the Trust are the promotion, Memorial Lecture support and advancement of the causes that Nani January 2010 Palkhivala ceaselessly espoused, such as democratic institutions, personal and civil liberties and rights enshrined in the Constitution, a society governed by just, fair and equitable laws and the institutions that oversee them, the primacy of liberal economic thinking for national development and preservation of India’s priceless heritage in all its aspects. The Trust is registered under the Bombay Public Trusts Act, 1950. The Trustees are: Y.H. Malegam (Chairman), F.K. Kavarana, Bansi S. Mehta, Deepak S. Parekh, H. -

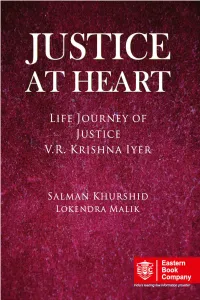

Justice at Heart Life Journey of Justice V.R

Justice at Heart Life Journey of Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer General Editor Abhinandan Malik BA, LL B (Hons) (NALSAR), LL M (Univ. of Toronto) Justice at Heart Life Journey of Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer Salman Khurshid BA (Hons) Delhi, MA (Oxon), BCL Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India & Former Union Minister of Law & Justice and External Affairs Dr Lokendra Malik LL B, LL M, Ph D, LL D (NLS Bangalore) Advocate, Supreme Court of India with a Foreword by P.P. R ao Senior Advocate Supreme Court of India Eastern Book Company Lucknow EASTERN BOOK COMPANY Website: www.ebc.co.in, E-mail: [email protected] Lucknow (H.O.): 34, Lalbagh, Lucknow-226 001 Phones: +91–522–4033600 (30 lines), Fax: +91–522–4033633 New Delhi: 5–B, Atma Ram House, 5th Floor 1, Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi-110 001 Phones: +91–11–45752323, +91–9871197119, Fax: +91–11–41504440 Delhi: 1267, Kashmere Gate, Old Hindu College Building, Delhi-110 006 Phones: +91–11–23917616, +91–9313080904, Fax: +91–11–23921656 Bangalore: 25/1, Anand Nivas, 3rd Cross, 6th Main, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560 009, Phone: +91–80–41225368 Allahabad: Manav Law House, Near Prithvi Garden Opp. Dr. Chandra’s Eye Clinic, Elgin Road, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211 001 Phones: +91–532–2560710, 2422023, Fax: +91–532–2623584 Ahmedabad: Satyamev Complex-1, Ground Floor, Shop No. 7 Opp. High Court Gate No. 2 (Golden Jubilee Gate) Sarkhej — Gandhinagar Highway Road, Sola, Ahmedabad-380 060 Phones: +91–532–2560710, 2422023, Fax: +91–532–2623584 Nagpur: F–9, Girish Heights, Near LIC Square, Kamptee Road, Nagpur-440 001 Phones: +91–712–6607650, +91–7028924969 www.facebook.com/easternbookcompany www.twiter.com/ebcindia Shop online at: www.ebcwebstore.com First Edition, 2016 ` 595.00 [Paperback] All rights reserved. -

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of SIKH AFFAIRS NOVEMBER 2009 Volume 19 No. 2

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS NOVEMBER 2009 Volume 19 No. 2 Published By: The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246 University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, Alberta T6G 2S5 CANADA E-mail: <[email protected]> http://www.yahoogroups.com/group/IntJSA ISSN 1481-5435 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIKH AFFAIRS Editorial Board ADVISORS Dr S S Dhami, MD Dr B S Samagh Dr Surjit Singh Prof Gurtej Singh, IAS Usman Khalid New York, USA Ottawa, CANADA Williamsville, NY Chandigarh Editor, J LISA, U K J S Dhillon “Arshi” M S Randhawa Dr Sukhjit Kaur Gill Gurmit Singh Khalsa MALAYSIA Ft. Lauderdale, FL CA Chandigarh AUSTRALIA Managing Editor and Editor in Chief: Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon The Sikh Educational Trust Box 60246, University of Alberta Postal Outlet EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA E-mail:<[email protected]> NOTE: Views presented by the authors in their contributions in the journal are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Editor in Chief, the Editorial Advisors, or the publisher. SUBCRIPTION: US$85.00 per anum plus 5% GST plus postage and handling (by surface mail) for institutions and multiple users. Personal copies: US$30.00 plus & 5% GST plus postage and handling (surface mail). Orders for the current and forthcoming issues may be placed with the Sikh Educational Trust, Box 60246, Univ of AB Postal Outlet, EDMONTON, AB T6G 2S5 CANADA. E-mail: [email protected] The Sikh Leaders, Freedom Fighters and Intellectuals To bring an end to tyranny it is a must to punish the terrorist -Baba (General) Banda Singh Bahadar Sikhs have only two options: slavery of the Hindus or struggle for their lost sovereignty and freedom -Sirdar Kapur Singh, ICS, MP, MLA and National Professor of Sikhism I am not afraid of physical death; moral death is death in reality Saint-soldier Jarnail Singh Khalsa Martyrdom is our ornament -Bhai Awtar Singh Brahma (General) We do not fear the terrorist Hindu regime.