SCQ10302 02 Henderson 198..219

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

8 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 a B C D a B

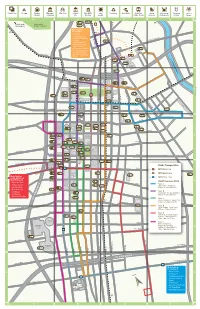

Public Plaza Art Spot Farmers Museum/ Bike Path Cultural Eco-LEED Solar Recycling Best Walks Light Rail Green Vegetarian Historical Special Market Institution Site Building Energy Public Transit Business Natural Cafe Feature Garden A B C D 7 3 Main St. Griffith Park/ Elysian Park/ Observatory Dodger Stadium 1 Metro Gold Line to Pasadena • Cornfield • Arroyo Seco Park • Debs Park-Audubon Broadway Society 8 Cesar Chavez Ave. 1 • Lummis House & 1 Drought Resistant Demo. Garden • Sycamore Grove Park 3 • S. Pasadena Library MTA • Art Center Campus Sunset Blvd. • Castle Green Central Park 3 Los Angeles River Union 6 Station 101 F R E E W AY 13 LADWP 1 Temple St. 12 12 10 9 8 Temple St. 2 2 San Pedro St. Broadway Main St. Spring St. 11 Los Angeles St. Grand Ave. Grand Hope St. 10 Figueroa St. Figueroa 1 11 9 3 3 Hill St. 1st St. 4 10 Alameda St. 1st St. Central Ave. Sci-Arc Olive St. Olive 7 1 2nd St. 2nd St. 6 5 8 6 2 3rd St. 4 3rd St. Flower St. Flower 4 3 2 W. 3rd St. 6 5 11 4 1 8 4th St. 4th St. 3 3 3 2 7 3 1 5 5th St. 1 5 12 5th St. 8 2 1 7 6 5 2 W. 6th St. 3 6th St. 3 7 6th St. 10 6 3 5 6 4 Wilshire Blvd. 9 14 Public Transportation 7th St. MTA Red Line 6 4 3 7 MTA Gold Line 7th St. 2 2 Metro Red Line to Mid-Wilshire & 5 MTA Blue Line North Hollywood 4 8th St. -

Imagine Pershing Square: Experiments in Cinematic Urban Design

Imagine Pershing Square: Experiments in Cinematic Urban Design By John Moody Bachelor of Arts in Film and Video Pacific University Forest Grove, Oregon (2007) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2016 © 2016 John Moody. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author_________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning (May 19, 2016) Certified by _____________________________________________________________ Anne Whiston Spirn, Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by______________________________________________________________ Associate Professor P. Christopher Zegras Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning 1 2 Imagine Pershing Square: Experiments in Cinematic Urban Design By John Moody Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 19, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment ofThesis the Requirements Supervisor: Anne for the Whiston Degree Spirn of Master in City Planning Title: Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning ABSTRACT Each person experiences urban space through the shifting narratives of his or her own cultural, economic and environmental perceptions. Yet within dominant urban design paradigms, many of these per- ceptions never make it into the public meeting, nor onto the abstract maps and renderings that planners and - designers frequently employ. This thesis seeks to show that cinematic practice, or the production of subjec tive, immersive film narratives, can incorporate highly differentiated perceptions into the design process. -

Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Quarter Research Team Building Site Name City Spring 2000 Winter 1996 Alesco Art Deco Architecture Winter 1996 Dameron Paul Revere Williams Winter 1996 Deffis-Whittaker Art Direction Winter 1996 Ekstrom William Morris Winter 1996 Kapoor Old Saddleback Mountain Winter 1996 Schaeffer Japanese Gardens Winter 1996 Shelton Bernard Maybeck Summer 1995 Stambaugh Preservation Movement Summer 1994 Anguiano Zig-Zag Architecture Summer 1994 Nix The California Bungalow Winter 1994 Ruiz Julia Morgan Summer 1993 Myers Frank Lloyd Wright & Michael Graves Summer 1993 Wallace Golden Age of Theatres in America Fall 1991 Spring 2001 Merendino Ramona Convent Alhambra Spring/Sum.2011 Anderson & Hinkley Pacific Electric Company Alta Dena Summer 1995 Guesnon Sam Maloof : a man of Alta Loma wood Winter 2014 Depew & Moulina Carnegie Library Anaheim 241 S. Anaheim Blvd. Winter 2010 Ta & Webster Kraemer Building Anaheim 201 E. Center Street Winter 2006 Giacomello & Kott Kraemer Building Anaheim Winter 2002 Corallo & Golish 1950’s Post-Modern Anaheim “Googie” Architecture of Anaheim and the Anaheim Convention Center’ Arena Building Winter 1999 Drymon Hatfield House Anaheim Summer 1994 Cadorniga St. Catherine’s Miltary Anaheim School Winter 1993 Ishihara Ferdinand Backs House Anaheim Winter 2001 Brewsaugh Santa Anita Park Arcadia Fall 1998 Garcia Santa Anita Depot Arcadia Summer 1995 Eccles Arrowhead Springs Spa Arrowhead Spring 2000 Dang Tuna Club Avalon Winter 1998 Daniels Catalina Casino Avalon Winter 1998 Lear Old State Capitol Benicia Winter -

“Ready for Its Close Up, Mr. Demille”

Hollywood Heritage is a non- profit organization dedicated to preservation of the historic built environment in Hollywood and to education about the early film industry and the role its pioneers played in shaping Summer 2012 www.hollywoodheritage.org Volume 31, Number 2 Hollywood’s history. The Barn “Ready For Its Close Up, Mr. DeMille” n 2011, with the upcoming centennial an- Hollywood Heritage $5,000 and Paramount cluded that there was some lead paint present niversaries of Paramount Pictures and the Pictures matched that and more, giving in a few locations. filming by Cecil B. DeMille of Hollywood’s $10,000. These two gifts resulted in available Michael Roy of Citadel recommended Ifirst full-length feature film, funding of $15,000 for the project. American Technologies Inc. (“ADT”) to do The Squaw Man, Hollywood Heritage recognized that the The project began with the engagement of the required lead abatement work. ADT, a Lasky-DeMille Barn (“Barn”), home of the Historic Resources Group (“HRG”) to con- firm that was also used by Paramount, gave a Hollywood Heritage Museum, was in need of a duct a paint study of the Barn to determine the discounted proposal to do the work. This in- face lift. An interior upgrade of the archive area Barn’s original colors. After gathering paint cluded a low level power wash of the building had recently been completed with a donation samples from the building and examining re- to prepare it for painting. A 40-foot “Knuckle from the Cecil B. DeMille Foundation, but search gathered by Hollywood Heritage, HRG Boom” was needed for the work, which was ac- there was more to be done. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No.CF No. Adopted Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) & 535 N. Main St 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 Cesar Chavez Av 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill8/6/1962 Dismantled 05/1969; Relocated to Hill Street Between 3rd St. & 4th St. in 1996 5 The Salt Box (Former Site of) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 Relocated to (Now Hope Street) Heritage Square in 1969; Destroyed by Fire 10/09/1969 6 Bradbury Building 216-224 W. 3rd Street 9/21/1962 300-310 S. Broadway 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock 72-77 Patrician Way 11/16/1962 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road Eagle Rock View Drive North Figueroa (Terminus) 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E. 107th Street 16 Saint Joseph's Church (site of) 1200-1210 S. -

LACEA Alive July2003 10.Qxd

4 May 2005 I City Employees Club of Los Angeles, Alive! w ww.cityemployeesclub.com Some Past L.A. Mayors Made History, Notoriety Comes ith the anticipation of the General Election May 17, it seemed appropriate to give by Hynda Rudd, Wthumbnail sketches of some of the mayors in the history of the City of Los Angeles. City Archivist (Retired), Each mayor has brought his own character to the office, but due to space limitation only a Alive! and Club Member few of the distinguished can be profiled here. Meredith Snyder’s second term, 1900-02, continued to revolve around water and elec- tricity. The Third Street Tunnel that col- lapsed in 1900, and was rebuilt, was bored through Bunker Hill from Hill street to Hope, making the Hill more accessible to business activity. During his third term from 1903-04, the 1889 City charter was amend- ed. The Civil Service Commission (precur- sor to the Personnel Department) was estab- lished. Snyder ran again in 1905, but was defeat- ed by the Republican Los Angeles Times retaliation due to a 1904 political disagree- Stephen Clark Foster Prudent Beaudry (1874-76) Cameron Erskine Thom ment with the newspaper. He remained (1854-55, 1856) Mr. Beaudry was a French Canadian from (1882-84) involved in civic activities for the next 15 years. Then in 1919, “Pinky/Pinkie” returned Mr. Foster was not the composer. Mayor Montreal. He served on the City Council Cameron E. Thom was a Southern gentle- for his fourth term as mayor. His appeal to Foster was an 1840 Yale graduate who came prior to being mayor. -

Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913, Containing the Reminiscences of Harris Newmark

Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913, containing the reminiscences of Harris Newmark. Edited by Maurice H. Newmark; Marco R. Newmark HARRIS NEWMARK AET. LXXIX SIXTY YEARS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 1853-1913 CONTAINING THE REMINISCENCES OF HARRIS NEWMARK EDITED BY MAURICE H. NEWMARK MARCO R. NEWMARK Every generation enjoys the use of a vast hoard bequeathed to it by antiquity, and transmits that hoard, augmented by fresh acquisitions, to future ages. In these pursuits, therefore, the first speculators lie under great disadvantages, and, even when they fail, are entitled to praise.— MACAULAY. WITH 150 ILLUSTRATIONS Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913, containing the reminiscences of Harris Newmark. Edited by Maurice H. Newmark; Marco R. Newmark http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.023 NEW YORK THE KNICKERBOCKER PRESS 1916 Copyright, 1916 BY M. H. and M. R. NEWMARK v TO THE MEMORY OF MY WIFE v In Memoriam At the hour of high twelve on April the fourth, 1916, the sun shone into a room where lay the temporal abode, for eighty-one years and more, of the spirit of Harris Newmark. On his face still lingered that look of peace which betokens a life worthily used and gently relinquished. Many were the duties allotted him in his pilgrimage splendidly did he accomplish them! Providence permitted him the completion of his final task—a labor of love—but denied him the privilege of seeing it given to the community of his adoption. To him and to her, by whose side he sleeps, may it be both monument and epitaph. Thy will be done! M. -

S Los Angeles and Disneyland/Orange County

California’s Los Angeles and Disneyland/Orange County Los Angeles and Orange County – Images by Lee Foster by Lee Foster No California urban scene surpasses Los Angeles and Orange County when sheer enthusiasm and brash exuberance are at issue. The Los Angeles region is a scene of worlds within worlds, ranging from the sun and surf worshippers at Venice Beach to the robust Little Saigon enclave of Vietnamese ex-patriots in Westminster, Orange County. Los Angeles, or LA as it is commonly called, boasts an unusual diversity of cultures and lifestyles within its neighborhoods. It is a melange of movie sets, oil wells, neon strips, sprawling suburbs, and broad boulevards. Wilshire Boulevard winds through Beverly Hills, home of movie stars and the site of eclectic boutiques. Hollywood and Sunset Boulevards pulsate in a neon glow, with nightclubs, bars, and restaurants. The lush, sprawling campus of UCLA lies in Westwood, a community with a college town feeling. Venice Beach is famous for its promenade where muscle builders, volleyball players, inline skaters, and strollers come to enjoy the sun and each other. Downtown, the Civic Center and futuristic ARCO plaza area blooms with skyscrapers. Little Tokyo and Chinatown are only minutes away. All these elements make LA special. Steady sunshine and a salubrious climate lend a relaxed flavor to the otherwise fast- paced life on the freeways. Weather is mild, even in winter, and the 14 inches of annual rainfall occurs mostly from November to March. A tinge of smog and the threat of congestion are the down side of life in LA. -

Las Angelitas Del Pueblo Newsletter— Spring 2013 El Pueblo De Los Angeles Historical Monument

Las Angelitas del Pueblo Newsletter— Spring 2013 El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument www.lasangelitas.org IN THIS ISSUE El Pueblo News 1 Events 2 Chinatown 3 Tour Angel News & 4 Notes Recent Stats NEWS AT EL PUEBLO Suellen Cheng announced that the Sepulveda House has re-opened. Entry is from Olvera Street next to the Tropical America exhibit. Docents may want to mention all the museums available at El Pueblo: Avila House, Chinese-American Museum, Historic Firehouse, Historic Placita Church, Siqueiros Interpretive Center and La Plaza de Cultura y Artes. The Italian Hall is finally being refurbished and brought up to code standards as the result of a $1,000,000 grant. Work will include a new roof, new floors and other work to be finished on the interior of the building. It will be open to the public some time in 2014. The most exciting news concerns the Merced Theatre. Los Angeles public access TV station, L.A. City View Channel 35, will establish its headquarters in the building with a central studio and office space. Improvements will include: First Floor Studio, Second Floor Theatre, Third Floor office space. Funding for the project comes from Public Education & Governmental Access fund. All litigation concerning the use of Pico House has been cleared up. El Pueblo would like to lease out office space on the second and third floors when the restrooms are repaired. First floor will remain available for art shows, meetings and party gatherings. Bike Nation is establishing a kiosk on Alameda Street where bicyclists can rent, ride and return bikes for a fee . -

My Seventy Years in California, 1857-1927, by J.A. Graves

My seventy years in California, 1857-1927, by J.A. Graves MY SEVENTY YEARS IN CALIFORNIA J. A. GRAVES MY SEVENTY YEARS IN CALIFORNIA 1857-1927 By J. A. GRAVES President Farmers & Merchants National Bank of Los Angeles Los Angeles The TIMES-MIRROR Press 1927 COPYRIGHT, 1927 BY J. A. GRAVES My seventy years in California, 1857-1927, by J.A. Graves http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.095 LOVINGLY DEDICATED TO MY WIFE ALICE H. GRAVES PREFACE Time flies so swiftly, that I can hardly realize so many years have elapsed since I, a child five years of age, passed through the Golden Gate, to become a resident of California. I have always enjoyed reading of the experiences of California pioneers, who came here either before or after I did. The thought came to me, that possibly other people would enjoy an account of the experiences of my seventy years in the State, during which I participated in the occurrences of a very interesting period of the State's development. As, during all of my life, to think has been to act, this is the only excuse or apology I can offer for this book. J. A. GRAVES. ix CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I FAMILY HISTORY. MARYSVILLE IN 1857. COL. JIM HOWARTH 3 II MARYSVILLE BAR IN 1857. JUDGE STEPHEN J. FIELD ITS LEADER. GEN. GEO. N. ROWE. PLACERVILLE BAR AN ABLE ONE 13 III FARMING IN EARLY DAYS IN CALIFORNIA. HOW WE LIVED. DEMOCRATIC CELEBRATION AT MARYSVILLE DURING THE LINCOLN-MCCLELLAN CAMPAIGN 25 IV SPORT WITH GREYHOUNDS. MY FIRST AND LAST POKER GAME 36 V MOVING FROM MARYSVILLE TO SAN MATEO COUNTY 39 VI HOW WE LIVED IN SAN MATEO COUNTY 43 VII BEGINNING OF MY EDUCATION 46 VIII REV. -

Los Angeles Et Ses Environs

77 Index Les numéros de page en gras renvoient aux cartes. A Bug’s Land, A (Anaheim) 46 Burbank (San Fernando Valley) 40 Adamson House (Malibu) 28 achats 76 Adventureland (Disneyland Park) 44 hébergement 61 Aéroports Bob Hope Airport (Burbank) 5 John Wayne Airport (Orange County) 5 C Long Beach Municipal Airport (Long Beach) 5 Cabrillo Marine Aquarium (San Pedro) 32 Los Angeles International Airport (Los Angeles) 4 California African American Museum (Los Ahmanson Theatre (Los Angeles) 15 Angeles) 17 American Cinematheque (Hollywood) 19 California Plaza (Los Angeles) 15 Anaheim (Orange County) 43 California Science Center (Los Angeles) 17 achats 76 Capitol Records Tower (Hollywood) 19 hébergement 62 Casino (Catalina Island) 36 sorties 74 Catalina Island Conservancy (Catalina Island) 36 Angel’s Flight Railway (Los Angeles) 15 Catalina Island Aquarium of the Pacific (Long Beach) 34 (Long Beach et ses environs) 34, 35 Arcade Lane (Pasadena) 37 achats 76 Autry National Center of the American West hébergement 58, 60 (Los Feliz) 22 Celebrate! A Street Party (Anaheim) 44 Avalon (Catalina Island) 35, 36 Central Library (Los Angeles) 16 Avila Adobe (Los Angeles) 11 City Hall (Los Angeles) 14 City Hall (Pasadena) 37 B Civic Center (Los Angeles) 14 Colorado Boulevard (Pasadena) 37 Baignade Conservancy House (Catalina Island) 36 Los Angeles et ses environs 47 Craft and Folk Art Museum (Wilshire) 26 Bel Air (Westside) 27 Critter Country (Disneyland Park) 44 hébergement 55 Culver City Art District (Culver City) 28 restaurants 67 Culver City (Westside)