Esg Disclosure in Comparative Perspective: Optimizing Private Ordering in Public Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of the Recognized Foreign Exchanges Relative to the Reporting Requirement (3Rd December 2007)

List of the recognized foreign exchanges relative to the reporting requirement (3rd December 2007) Art. 15 para. 2 SESTA determines that securities dealers must report all the infor- mation necessary to ensure a transparent market (reporting requirement). In Art. 2 following SESTO-SFBC the appropriate implementing regulations are determined. Exceptions of the reporting requirement are recorded in Art. 4 SESTO-SFBC. Art. 4 letter a SESTO-SFBC determines that the securities dealer shall not be obliged to report transactions abroad in foreign securities admitted for trading on a Swiss stock exchange, provided that they are conducted on a foreign stock exchange recognized by Switzerland. According to established practice relative to the release of the reporting require- ment, recognized exchanges are the exchanges that are united in the World Fed- eration of Exchanges and/or the Federation of European Stock Exchanges (FESE). All foreign exchanges that are authorized by the Swiss Federal Banking Commis- sion in accordance with Art. 14 SESTO are also recognized exchanges concerning this matter, even they are neither member of the World Federation of Exchanges nor of the FESE. As an exception to this rule, besides the Deutsche Börse AG (member of World Federation of Exchanges) also the remaining German (regional) exchanges are recognized in this context. Name Location AMERICAN STOCK EXCHANGE New York, USA AMMAN STOCK EXCHANGE Amman, JORDAN ATHENS EXCHANGE Athens, GREECE AUSTRALIAN STOCK EXCHANGE Sydney, AUSTRALIA BAYERISCHE BÖRSE Munich, GERMANY BERMUDA STOCK EXCHANGE Hamilton, BERMUDA BOLSA DE COMERCIO DE BUENOS AIRES Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA BOLSA DE COMERCIO DE SANTIAGO Santiago, CHILE BOLSA DE VALORES DE COLOMBIA Bogota, COLOMBIA BOLSA DE VALORES DE LIMA Lima, PERU BOLSA DE VALORES DO SAO PAULO Sao Paulo, BRAZIL Name Location BOLSA MEXICANA DE VALORES Mexico, MEXICO BOLSAS Y MERCADOS ESPANOLES Barcelona, Bilbao, Madrid, Valencia, SPAIN BOMBAY STOCK EXCHANGE LTD. -

South Africa and Namibia

SOUTH AFRICA AND NAMIBIA SOUTH AFRICA $881.61 Bn $200.29 Bn Equity Market Debt Market 372 125 136% 260% 59% Capitalization Capitalization Number of Number of Domestic Total Equity Debt Market listed issuers Equity Market Market Cap/ Cap/GDP companies (bonds) Cap/GDP GDP 91,716,796,484 $2,127.21 Bn Equity Market Share Volume Traded Debt Market Total Nominal Traded NAMIBIA $138.37 Bn* $2.72 Bn 17% 953%* 19% Equity Market Debt Market 44* 10 Domestic Total Equity Domestic Capitalization Capitalization Number of Number of Equity Market Market Cap/ Debt Market listed issuers Cap/GDP GDP Cap/GDP companies (bonds) 193,100,874 41,296,398 Equity Market Share Volume Traded Debt Market Instrument Volume Traded *Includes dual-listings and ETFs. CFA Institute Research Foundation | 1 SOUTH AFRICA AND NAMIBIA • 1881: Kimberley Royal 1880s Stock Exchange established • 1886: Gold discovered on the reef • 1895: Durban Roodepoort • 1887: Johannesburg Stock 1890s Deep listed on the JSE Exchange (JSE) established • 1897: South African Breweries (SAB) listed on the JSE • 1901: Cape Town stock exchange established 1900s • 1904: Namibian Stock Exchange (NSX) founded 1910s • 1910: NSX closed • 1947: Stock Exchanges 1940s Control Act was passed in SA • 1963: JSE joins World 1960s Federation of Exchanges • 1990: Namibian independence from South Africa • 1992: NSX established (second time); First • 2000: JSE moves to corporate bond (SAB) issued 1990s Sandton; First ETF listed on in South Africa the JSE • 1996: Open outcry trading • 2001: FTSE agreement with ceases -

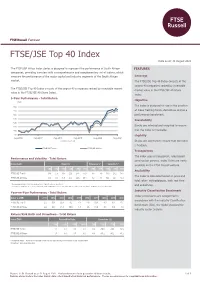

FTSE/JSE Top 40 Index

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE/JSE Top 40 Index Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE/JSE Africa Index Series is designed to represent the performance of South African FEATURES companies, providing investors with a comprehensive and complementary set of indices, which measure the performance of the major capital and industry segments of the South African Coverage market. The FTSE/JSE Top 40 Index consists of the largest 40 companies ranked by investable The FTSE/JSE Top 40 Index consists of the largest 40 companies ranked by investable market market value in the FTSE/JSE All-Share value in the FTSE/JSE All-Share Index. Index. 5-Year Performance - Total Return Objective The index is designed for use in the creation of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a performance benchmark. Investability Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure that the index is investable. Liquidity Stocks are screened to ensure that the index is tradable. Transparency The index uses a transparent, rules-based Performance and Volatility - Total Return construction process. Index Rules are freely Index (ZAR) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** available on the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE/JSE Top 40 -0.6 2.5 14.5 22.6 27.8 53.0 8.5 8.9 17.3 23.2 15.5 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE/JSE All Share -0.1 4.0 15.9 25.2 26.6 49.1 8.2 8.3 16.4 22.5 15.2 total return methodologies, both real time * Compound annual returns measured over 3 and 5 years respectively and end-of-day. -

Purple-Group-Annual-Report-2016

2Awards and Highlights 1 Purple Philosophy 2 Chairman’s Letter 4 Chief Executive Officer’s Letter 5 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 6 12Ethical Leadership 38Directors’ Responsibility 86 Notice of Annual General Meeting 86 and Corporate Citizenship 12 for Financial Reporting 38 Shareholder Rights 90 Summary Governance Results 19 Group Secretary’s Report 39 Brief Curriculum Vitae of Our People 20 Directors’ Report 40 Directors Standing for Re-election 90 Our Leadership Report of the Audit Committee 42 Form of Proxy 91 Executive Team Management Team 22 Report of the Independent Auditor 43 Notes to the Form of Proxy 92 Board Members 24 Consolidated Statement Corporate Information 93 of Profit or Loss 44 Your Thoughts Our Team 26 Consolidated Statement of 94 Other Comprehensive Income 45 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 46 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 47 Consolidated Statement 28 of Cash Flows 48 Navigate the Markets 28 Notes to the Consolidated Annual Our Brands – Emperor 30 Financial Statements 49 Our Brands – EasyEquities 32 Shareholder Analysis 85 Our Brands – GT247.com 34 Our Brands – GT Private Broking 36 INVESTING AND TRADING SOLUTIONS FOR EVERYONE First World Trader (FWT) t/a Emperor Asset Management Proprietary First World Trader Nominees Proprietary GT247.com Limited (EAM) Limited (FWTN) Non-discretionary Category I FAIS licence, Discretionary Category II FAIS licence, which Approved by the FSB to operate and hold which provides FWT the ability to conduct provides EAM the ability to conduct an clients’ assets in the name of the nominee. an intermediary and advisory service on intermediary investment management service STRATE approval to hold equity securities on derivatives, shares, money market, retail on derivatives, shares, money market and behalf of clients. -

Wealth Management | Global After the Storm Covid 19 Has Permanently Changed the Way Wealth Managers Deliver Advice and Serve Their Clients

M BLUEPAPER Wealth Management | Global After the Storm Covid 19 has permanently changed the way Wealth Managers deliver advice and serve their clients. To drive outperformance over the next 5+ years, firms should double down on technology investments, strategically cut costs, build differentiated product offerings and consider inorganic opportunities. Oliver Wyman is a global leader in management consulting. For more information, visit www.oliverwyman.com. Oliver Wyman is not authorized or regulated by the PRA or the FCA and is not providing investment advice. Oliver Wyman authors are not research analysts and are neither FCA nor FINRA registered. Oliver Wyman authors have only contributed their expertise on business strategy within the report. Oliver Wyman’s views are clearly delineated. The securities and valuation sections of this report are the work of Morgan Stanley only and not Oliver Wyman. For disclosures specifically pertaining to Oliver Wyman, please see the Disclosure Section located at the end of this report. Morgan Stanley does and seeks to do business with companies covered in Morgan Stanley Research. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of Morgan Stanley Research. Investors should consider Morgan Stanley Research as only a single factor in making their investment decision. M BLUEPAPER Authors MORGAN STANLEY OLIVER WYMAN Betsy L. Graseck, CFA1 Kai Upadek EQUITY ANALYST PARTNER +1 212 761 8473 +44 20 7852 7657 [email protected] [email protected] Magdalena L Stoklosa, CFA2 Christian Edelmann EQUITY ANALYST PARTNER +44 20 7425 3933 +44 20 7852 7557 [email protected] [email protected] Nick Lord3 Bradley Kellum EQUITY ANALYST PARTNER +65 6834 6746 +1 646 364 8425 [email protected] [email protected] Michael J. -

Naspers Limited

NASPERS LIMITED (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) (Registration number 1925/001431/06) JSE share code: NPN ISIN: ZAE000015889 LSE code: NPSN ISIN: US6315121003 (Naspers or the Company) Posting of circular and notice of general meeting Naspers N Shareholders and A Shareholders (Shareholders) are referred to the announcements made by the Company on: (i) 25 March 2019 in relation to the Company's intention to form a new global consumer internet group, comprising the Naspers group's international internet assets (Proposed Transaction). These assets will be held by Myriad International Holdings N.V. (previously referred to as NewCo and to be renamed Prosus N.V.), an existing subsidiary of Naspers incorporated in accordance with Dutch laws (Prosus). The Prosus N Ordinary Shares are proposed to be admitted to listing and trading on Euronext Amsterdam and, as a secondary, inward listing on the Main Board of the JSE (ii) 29 May 2019 in relation to the posting of a circular (Original Circular) and notice of a general meeting of Shareholders pertaining to the Proposed Transaction, and (iii) 21 June 2019 pertaining to the withdrawal of the notice convening such general meeting of Shareholders and the cancellation of the general meeting as a result of an administrative error. Shareholders are hereby advised that a revised circular (Circular), containing the new timetable for the Proposed Transaction has been posted to Shareholders today, Friday 19 July 2019. The Circular includes a notice convening a new general meeting of Shareholders (General Meeting) to be held on Friday 23 August 2019, immediately following the annual general meeting of the Company to be held at 11:15 on Friday 23 August 2019 at the Daisy Room, second floor, Cape Town International Convention Centre 2, corner of Heerengracht and Rua Bartholomeu Dias, Foreshore, Cape Town, South Africa at which Shareholders will be requested to consider, and if deemed fit, pass the Resolution required to be adopted to implement the Proposed Transaction. -

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange Nicky Newton-King: Deputy CEO

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange Nicky Newton-King: Deputy CEO www.jse.co.za www.jse.co.za Copyright© JSE Limited 2009 1 A bit of history – where we were www.jse.co.za 2 A bit of history – where we are www.jse.co.za 3 The exchange value chain – vertical and horizontal integration… Front line regulator LISTING TRADING Equity Commodity Interest Rate Equities Derivatives Derivatives Products CLEARING SETTLEMENT Data Products www.jse.co.za 4 The JSE today • Front line regulator − Of primary and secondary markets • Listing, Trading, Clearing and Surveillance across 4 Markets − Equities Main Board and AltX − Equity Derivatives – SSF, index derivatives, currency futures, can-do options to name a few − Commodity Derivatives – maize, wheat, soya, sunflowers, and CME-referenced corn, crude oil, gold, and platinum − Interest Rate Products • Clearing and risk management services • Settlement − Own just under 45% of Strate − Guarantee of central order book equity trades • Data sales • Back office technology • Self-regulatory organisation and listed company www.jse.co.za − JSE regulated by FSB www.jse.co.za 5 The JSE today • World class standards − South Africa ranked first for securities market regulation according to the WEF Global Competitiveness Report 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 − Long term member of World Federation of Exchanges • Regulatory framework − Securities Services Act to be replaced by the Financial Markets Bill − Role of FSB, NT and SARB • Governance and auditing standards − King Reports − Listings requirements • World class technology • -

List of Approved Bodies (For Consultation) ASIC ‘Regulated (I.E

List of approved bodies (for consultation) ASIC ‘regulated (i.e. recognised) financial ASIC ‘relevant financial markets’ Clearing house/Recognised Investment markets’ exchanges ASX Clear (Futures) Pty Limited BATS Options BME Clearing ASX Clear Pty Limited Borsa Istanbul Cantor Clearinghouse, L.P ASX Limited Boston Options Exchange Cassa di Compensazione e Garanzia S.p.A (CCG) CCP Austria Abwicklungsstelle für Athens Exchange Derivatives Market BSE Limited (Bombay Stock Exchange) Börsengeschäfte GmbH (CCP .A) Athens Exchange Clearing House (Athex Clear) Bursa Malaysia - Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Central Depository (Pte) Limited BM&FBOVESPA CEGH Gas Exchange of Vienna Stock Exchange Clearing Corporation Bourse de Montreal Chicago Climate Futures Exchange CME Clearing Europe Ltd Budapesti Értéktozsde (Budapest Stock Exchange) Chicago Mercantile Exchange CME Inc. CBOE Futures Exchange China Financial Futures Exchange Eurex Clearing AG Chicago Board of Trade Dalian Commodities Exchange European Central Counterparty N.V Chicago Board Options Exchange Dubai Gold & Commodities Exchange European Commodity Clearing CME Direct Dubai Mercantile Exchange HKFE Clearing Corporation Limited CME Globex EDGX Exchange, Inc Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited The Commodity Exchange, operated by Electronic Liquidity Exchange operated by ELX Commodity Exchange, Inc. (US) Futures LP ICAP Securities and Derivatives Exchange Limited Eurex Deutschland EPEX Spot SE ICE Clear Credit LLC Euronext Paris MATIF (Marché à Terme International de France) European Climate Exchange ICE Clear Europe Limited Euronext Paris MONEP (Marche des Options Negociables de Paris) European Energy Exchange ICE Clear Netherlands B.V. Hong Kong Futures Exchange Limited European Exchange ICE Clear Singapore ICE Futures Canada Hong Kong Exchange & Clearing Ltd ICE Clear US, Inc 1 ASIC ‘regulated (i.e. -

Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Cc: New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) London Stock Exchange (LSE) JSE Limited (JSE)

15 September 2020 To: Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) cc: New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) London Stock Exchange (LSE) JSE Limited (JSE) Notice of 2021 Interim Dividend Dates The proposed dates1 for the 2021 Interim Dividend of BHP Group Limited and BHP Group Plc are set out below. BHP’s Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) will operate in respect of the 2021 Interim Dividend. Full terms and conditions of the DRP and details about how to participate can be found at bhp.com. 2021 Interim Dividend Half Yearly Results Announcement and Dividend Determination 16 February 2021 Announcement of currency conversion into RAND 26 February 2021 Last day to trade cum dividend on JSE 2 March 2021 Ex-Dividend Date (JSE) 3 March 2021 Ex-Dividend Date (ASX, LSE and NYSE2) 4 March 2021 Record Date 5 March 2021 DRP and Currency Election date (including announcement of currency 8 March 2021 conversion ASX and LSE) Payment Date 23 March 2021 DRP Allocation Date (ASX and LSE) within ten business days after the 6 April 2021 payment date DRP Allocation Date (JSE), subject to the purchase of shares by the 6 April 2021 Transfer Secretaries in the open market, CSDP accounts credited/updated on or about3 BHP Group Plc shareholders registered on the South African section of the register will not be able to dematerialise or rematerialise their shareholdings between the dates of 3 March 2021 and 5 March 2021 (inclusive), nor will transfers between the UK register and the South African register be permitted between the dates of 26 February 2021 and 5 March 2021 (inclusive). -

Jseefficiency and Share Price Reaction to Forced

JSE EFFICIENCY AND SHARE PRICE REACTION TO FORCED FINANCIAL RESTATEMENTS Shaun Watson# Jacobus Rossouw+ University of the Free State University of the Free State [email protected] [email protected] February 2012 Abstract This study uses an event study methodology to empirically examine share price reaction to financial restatement announcements resulting from investigations or recommendations by the GAAP Monitoring Panel and tests, in semi-strong form, the efficiency of the Johannesburg Securities Exchange (JSE). The results indicate that companies making such financial restatement announcements experience significant negative standardised abnormal returns ten days before and five days subsequent to the announcement. As evidenced by the significant negative standardised abnormal returns, it would appear that the announcements convey new information to the market. Although the lack of consecutive negative standardised abnormal returns around the announcement date would suggest that the JSE is efficient in semi-strong form, the five-day time lag between the announcement date and the significant negative standardised abnormal return supports the rejection of semi-strong form efficiency of the JSE. Keywords JSE efficiency, restatement of financial statements, event study, abnormal returns, GAAP Monitoring Panel _________________________________ #Mr Shaun Watson is senior lecturer at the Centre of Accounting, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. +Prof Cobus Rossouw is associate professor at the Centre of Accounting, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences | JEF | October 2012 5(2), pp. 417-436 417 JSE EFFICIENCY AND SHARE PRICE REACTION TO FORCED FINANCIAL RESTATEMENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) posits that share prices in an efficient market will at any time fully reflect all available information. -

Capital Allocation Policy

Capital Allocation Policy 30 November 2020 Irongate Group Sydney Level 13, 95 Pitt Street NSW 2000 Melbourne +61 2 7906 2000 irongategroup.com.au Brisbane 1. ABOUT THIS POLICY 1.1 Policy statement The purpose of this Policy is to set out a procedure to ensure a fair and equitable allocation of Acquisitions amongst the Group. The Fund is listed on JSE and ASX. As such, this Policy must comply with the requirements of both the JSE and ASX. Where the requirement of one exchange is more stringent than the requirement of another exchange, compliance with the more stringent requirement is required. If it is not possible to comply with both the JSE LR and the ASX LR, the RE must comply with the rule or requirement of the Main Trading Exchange at the relevant time. 1.2 Defined terms Acquisition An acquisition opportunity for consideration by a Group member, including: • whole or partial interests in an asset; • whole or partial interests a Portfolio; • on-market assets/Portfolio opportunities; and • off-market assets/Portfolio opportunities, but does not include the following activity: • M&A activity involving a listed entity or an operating business; • properties adjoining an asset already owned by a Group member where that Group member is interested in acquiring the property; • situations where a vendor will not transact with an individual Group member, whereby it will be excluded from participating; and • Group member asset sales, unless the selling Group member(s) decides otherwise Act Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ASX ASX Limited or Australian -

Operating and Financial Results for the Six Months Ended 30 June 2021

Ope r at ing an d financi al r es ult s For t he six mont hs ended 30 June 2018 JOHANNESBURG, 26 August 2021: Sibanye Stillwater Limited (Sibanye-Stillwater or the Group) (JSE: SSW and NYSE: SBSW) is pleased to report operating results and condensed consolidated interim financial statements for the six months ended 30 June 2021. SALIENT FEATURES FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2021 • Profit attributable to shareholders of R24.8bn (US$1.7bn) • Record Adjusted Free Cash Flow (AFCF) of R17.3bn (US$1.2bn) – a 59% increase from R10.9bn (US$655m) for H1 2020 • Interim dividend of ~R8.5bn (US$565m) – 292 SA cps (77.21 US cents per ADR). Annualised dividend yield of 10% * • Continued capital allocation discipline − Borrowings (excl. non-recourse)** reduced by R12.2bn (US$508m) to R15.9bn (US$1.1bn) at the end of H1 2021 (vs H1 2020) − Further R5.0bn (US$354m) reduction from corporate bond buyback on 2 August 2021 − Share buyback program (5% of issued share capital) returning ~R9.6bn (US$700m) surplus cash to shareholders, once completed, will further enhance shareholder returns * Based on the closing share price of R59.66 at 30 June 2021 ** Refer note 10.2 (footnote 1) of the condensed consolidated interim financial statements US dollar SA rand Six months ended Six months ended Jun 2020 Dec 2020 Jun 2021 KEY STATISTICS Jun 2021 Dec 2020 Jun 2020 UNITED STATES (US) OPERATIONS PGM underground operations1,2 297,740 305,327 298,301 oz 2E PGM production2 kg 9,278 9,497 9,261 1,837 1,970 2,286 US$/2Eoz Average basket price R/2Eoz 33,261 32,026 30,621