Lnformanon to USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1967 to 2017 CANADA TRANSFORMED

FALL / WINTER 2017 1967 to 2017 CANADA TRANSFORMED RANDY BOSWELL DOMINIQUE CLÉMENT VICTOR RABINOVITCH KEN MCGOOGAN NELSON WISEMAN JACK BUMSTED VERONICA STRONG-BOAG JEAN-PHILIPPE WARREN JACK JEDWAB TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 INTRODUCTION MILESTONES, LEGACIES AND A HALF-CENTURY OF CHANGE Randy Boswell 7 HOW CANADIAN BOOMERS SPIRITED THE SIXTIES INTO THE 21ST CENTURY Ken McGoogan 11 “SHE NAMED IT CANADA BECAUSE THAT’S WHAT IT WAS CALLED”: LANGUAGE AND JUSTICE IN CANADA 2017+ Veronica Strong-Boag 15 CANADA’S RIGHTS CULTURE: FIFTY YEARS LATER Dominique Clément 20 AN EVER-CHANGING FACE AND IDENTITY Nelson Wiseman 24 AN UNEXPECTED CANADA Jean-Philippe Warren 28 50 YEARS OF CANADIAN CULTURE: THE ROOTS OF OUR MODEL AND THE BIG, NEW THREAT Victor Rabinovitch 33 HAS THE COUNTRY REALLY CHANGED ALL THAT MUCH IN THE PAST 50 YEARS? Jack Bumsted 36 VIVE LE QUÉBEC LIBRE @ 50: THE RISE AND DECLINE OF QUÉBEC’S INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENT, 1967-2017 Jack Jedwab CANADIAN ISSUES IS PUBLISHED BY ASSOCIATION FOR CANADIAN STUDIES BOARD OF DIRECTORS Canadian Issues is a quarterly publication of the Association Elected November 3, 2017 for Canadian Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. Canadian CELINE COOPER Montréal, Québec, Chairperson of the Board of Directors, Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by Columnist at the Montréal Gazette, PhD Candidate, the ACS is published in both French and English. All other OISE/University of Toronto articles are published in the language in which they are written. Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors THE HONOURABLE HERBERT MARX and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the ACS. -

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity

Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity by Megan De Roover A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Megan De Roover, December, 2012 ABSTRACT Internalizing Borderlands: the Performance of Borderlands Identity Megan De Roover Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Professor Martha Nandorfy In order to establish a working understanding of borders, the critical conversation must be conscious of how the border is being used politically, theoretically, and socially. This thesis focuses on the border as forcibly ensuring the performance of identity as individuals, within the context of borderlands, become embodiments of the border, and their performance of identity is created by the influence of external borders that become internalized. The internalized border can be read both as infection, a problematic divide needing to be removed, as well as an opportunity for bridging, crossing that divide. I bring together Charles Bowden (Blue Desert), Monique Mojica (Princess Pocahontas and the Blue Spots), Leslie Marmon Silko (Ceremony, Almanac of the Dead), and Guillermo Verdecchia (Fronteras Americanas) in order to develop a comprehensive analysis of the border and border identity development. In these texts, individuals are forced to negotiate their sense of self according to pre-existing cultural and social expectations on either side of the border, performing identity according to how they want to be socially perceived. The result can often be read as a fragmentation of identity, a discrepancy between how the individual feels and how they are read. I examine how identity performance occurs within the context of the border, brought on by violence and exemplified through the division between the spirit world and the material world, the manipulation of costuming and uniforms, and the body. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Susan Swan: Michael Crummey's Fictional Truth

Susan Swan: Michael Crummey’s fictional truth $6.50 Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2019 DAVID M. MALONE A Bridge Too Far Why Canada has been reluctant to engage with China ALSO IN THIS ISSUE CAROL GOAR on solutions to homelessness MURRAY BREWSTER on the photographers of war PLUS Brian Stewart, Suanne Kelman & Judy Fong Bates Publications Mail Agreement #40032362. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. PO Box 8, Station K, Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 New from University of Toronto Press “Illuminating and interesting, this collection is a much- needed contribution to the study of Canadian women in medicine today.” –Allyn Walsh McMaster University “Provides remarkable insight “Robyn Lee critiques prevailing “Emilia Nielsen impressively draws into how public policy is made, discourses to provide a thought- on, and enters in dialogue with, a contested, and evolves when there provoking and timely discussion wide range of recent scholarship are multiple layers of authority in a surrounding cultural politics.” addressing illness narratives and federation like Canada.” challenging mainstream breast – Rhonda M. Shaw cancer culture.” –Robert Schertzer Victoria University of Wellington University of Toronto Scarborough –Stella Bolaki University of Kent utorontopress.com Literary Review of Canada 340 King Street East, 2nd Floor Toronto, ON M5A 1K8 email: [email protected] Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/ support Vol. 27, No. 1 • January/February 2019 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Murray Campbell (interim) Kyle Wyatt (incoming) [email protected] 3 The Tools of Engagement 21 Being on Fire ART DIRECTOR Kyle Wyatt, Incoming Editor-in-Chief A poem Rachel Tennenhouse Nicholas Bradley ASSISTANT EDITOR 4 Invisible Canadians Elaine Anselmi How can you live decades with someone 22 In the Company of War POETRY EDITOR and know nothing about him? Portraits from behind the lens of Moira MacDougall Finding Mr. -

Fall 2019 Catalogue

—Ordering Information— For more information, or for further promotional materials, please contact: Daniel Wells | Publisher Biblioasis Email: [email protected] 1686 Ottawa Street, Suite 100 Windsor, ON Casey Plett | Publicity N8Y 1R1 Canada Email: [email protected] Orders: Vanessa Stauffer |Sales & Marketing www.biblioasis.com [email protected] Email: [email protected] on twitter: @biblioasis Phone: 519-915-3930 Distribution: University of Toronto Press 5201 Dufferin Street, Toronto, ON, M3H 5T8 Toll-free phone: 800-565-9533 / Fax: 800-221-9985 email: [email protected] Sales Representation: Ampersand Inc. Head office/Ontario Evette Sintichakis Pavan Ranu Suite 213, 321 Carlaw Avenue Ext. 121 Phone: 604-448-7165 Toronto, ON, M4M 2S1 [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 416-703-0666 Toll-free: 866-736-5620 Jenny Enriquez Fax: 416-703-4745 Ext. 126 Vancouver Island Toll-free: 866-849-3819 [email protected] Dani Farmer www.ampersandinc.ca Phone: 04-4481768 [email protected] Saffron Beckwith British Columbia/Alberta/Yukon/Nunavut Ext. 124 2440 Viking Way [email protected] Richmond, BC V6V 1N2 Alberta, Manitoba & Saskatchewan/NWT Phone: 604-448-7111 Jessica Price Morgen Young Toll-free: 800-561-8583 604-448-7170 Ext. 128 Fax: 604-448-7118 [email protected] [email protected] Toll-free Fax: 888-323-7118 Laureen Cusack Ali Hewitt Quebec/Atlantic Provinces Ext. 120 Phone: 604-448-7166 Jenny Enriquez [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 416-703-0666 Ext. 126 Toll Free 866-736-5620 Vanessa Di Gregoro Dani Farmer Fax: 416-703-4745 Ext. 122 Phone: 604-448-7168 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Laura MacDonald Jessica Price Ext. -

Chinatown Children During World War Two in the Jade Peony a Journal

Chinatown Children during World War Two in The Jade Peony Zhen Liu Shandong University (China) [email protected] A Journal of Canadian Literary and Cultural Studies ISSN 2254-1179 VOL. 7 (2018) pp. 25-35 • ARTICLES 6ƮƛƦƢƭƭƞƝ $ƜƜƞƩƭƞƝ 29/05/2017 26/01/2018 .ƞƲưƨƫƝƬ Asian Canadian literature; Chinese Canadian literature; Canadian literature $ƛƬƭƫƚƜƭ In The Jade Peony (1995) Wayson Choy captured vividly the lives of three children growing up in Vancouver’s Chinatown during the 1930s and 1940s when the Depression and the Second World War constituted the social backdrop. In the article, I argue that the Chinatown residents exemplify WKHW\SHRIYXOQHUDELOLW\GH¿QHGE\-XGLWK%XWOHUDVXSDJDLQVWQHVVDQGHVSHFDLOO\WKHFKLOGUHQ LQWKHQRYHOVXIIHUIURPDJUHDWHUYXOQHUDELOLW\DVWKH\DUHFDXJKWXSLQWKHFURVV¿UHRIERWKVLGHV *URZLQJXSLQWZRFRQÀLFWLQJFXOWXUHVDQGUHVWULFWHGWRWKHOLPLQDOFXOWXUDODQGSK\VLFDOVSDFHWKH children are disorientated and confused as if stranded in no man’s land. More importantly, in their serious struggles, the children show great resilience and devise their own strategies, such as for ming alliance with others, to survive and gain more space in spite of the many restraints imposed on them. 5ƞƬƮƦƞƧ En The Jade Peony (1995) Wayson Choy captura vívidamente las vidas de tres niños que crecen en el Chinatown de Vancouver durante las décadas de 1930 y 1940, con la Gran Depresión y la Segunda Guerra Mundial como telón de fondo social. En el artículo, argumento que los residentes HQ&KLQDWRZQHMHPSOL¿FDQHOWLSRGHYXOQHUDELOLGDGGH¿QLGDSRU-XGLWK%XWOHUFRPR³XSDJDLQVW ness”(2) y especialmente, que los niños en la novela sufren una gran vulnerabilidad al estar atra pados en medio del fuego cruzado mantenido por ambos sectores. Ya que crecen en dos culturas HQFRQÀLFWR\UHVWULQJLGDVDOHVSDFLROLPLQDOFXOWXUDO\ItVLFRORVQLxRVHVWiQGHVRULHQWDGRV\FRQ fundidos como si hubieran sido abandonados en tierra de nadie. -

![THE I]NTVERSITY of MANITOBA COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Beyond](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5884/the-i-ntversity-of-manitoba-copyright-permission-beyond-925884.webp)

THE I]NTVERSITY of MANITOBA COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Beyond

THE I]NTVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACTJLTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ¿súgJ COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Beyond Limits: Cultural Identity in Contemporary Canadian Fiction BY Alain Régnier A ThesislPracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree MASTER OFARTS Alain Régnier A 2007 Permission has been granted to the University of Manitoba Libraries to lend a copy of this thesis/practicum, to Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to lend a copy of this thesis/practicum, and to LAC's agent (UMlÆroQuest) to microfilm, sell copies and to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. Beyond Limits: Cultural Identity in Contemporary Canadian Fiction by Alain Régnier A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba O July, 2007 Abstract This thesis deals with the fictional works All That Matters by Wayson Choy, Monkey Beach by Eden Robinson and L'immense fatigue des pierres by Régine Robin, and the manner in which the authors of these texts have approached the issue of cultural identity from their particular vanfage point in Canadian society. Drawing significantly on the thoughts of Homi K. Bhabha and Judith Butler, the study explores the problem of cultural liminality and hybridity, and how identities come to be formed under such conditions. -

Diasporic Space in Wayson Choy's All That Matters1

Postcolonial Text, Vol 6, No 3 (2011) “His Paper Family Knew Their Place”: Diasporic Space in Wayson Choy’s All That Matters1 Alena Chercover University of Victoria I. Arrested Bodies: Diasporic Matters on the West Coast On the morning of August 13, 2010, a cargo ship called the MV Sun Sea pulled into Esquimalt Harbour on the southern tip of Vancouver Island. The ship had left Thailand ninety days earlier, filled with 493 Sri Lankan Tamils seeking refuge in North America. However, its arrival on Canada’s west coast followed weeks of government and media rhetoric announcing the pending invasion of the Canadian border by terrorists and human smugglers (Burgmann). Canadian border guards met and quickly relayed the migrants to awaiting cells at various detention centres in the lower mainland, while government officials declared the detainment of Tamil migrants necessary for public safety until their papers could be fully analyzed (“Tamil Migrants”). Dominating media coverage, the “processing” of paper identities began to eclipse the incarcerated bodies of Tamil migrants and, two months after their arrival on Canadian shores, more than 450 of the refugee claimants remained in a state of indefinite detention. Contrary to celebratory discourses of diasporic mobility in which, as James Clifford writes in his seminal 1994 essay, “separate places become effectively a single community” (303), the movement of bodies across geopolitical borders and within hostland communities remains fraught in the current transnational moment. Bodies marked by race and gender, as well as those lacking the material means of migration, risk becoming entangled in the legislative, systemic, social, and ultimately concrete barriers inscribed by both the host nation and the diaspora itself: for some, diasporic mobility simultaneously (and paradoxically) begets diasporic bondage. -

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave

Guillermo Verdecchia Theatre Artist / Teacher 46 Carus Ave. Toronto, ON M6G 2A4 (416) 516 9574 [email protected] [email protected] Education M.A University of Guelph, School of English and Theatre Studies, August 2005 Thesis: Staging Memory, Constructing Canadian Latinidad (Supervisor: Ric Knowles) Recipient Governor-General's Gold Medal for Academic Achievement Ryerson Theatre School Acting Program 1980-82 Languages English, Spanish, French Theatre (selected) DIRECTING Two Birds, One Stone 2017 by Rimah Jabr and Natasha Greenblatt. Theatre Centre, Riser Project, Toronto The Thirst of Hearts 2015 by Thomas McKechnie Soulpepper, Theatre, Toronto The Art of Building a Bunker 2013 -15 by Adam Lazarus and Guillermo Verdecchia Summerworks Theatre Festival, Factory Theatre, Revolver Fest (Vancouver) Once Five Years Pass by Federico Garcia Lorca. National Theatre School. Montreal 2012 Ali and Ali: The Deportation Hearings 2010 by Marcus Youssef, Guillermo Verdecchia, and Camyar Chai Vancouver East Cultural Centre, Factory Theatre Toronto Guillermo Verdecchia 2 A Taste of Empire 2010 by Jovanni Sy, Cahoots Theatre Rice Boy 2009 by Sunil Kuruvilla, Stratford Festival, Stratford. The Five Vengeances 2006 by Jovanni Sy, Humber College, Toronto. The Caucasian Chalk Circle 2006 by Bertolt Brecht, Ryerson Theatre School, Toronto. Romeo and Juliet 2004 by William Shakespeare, Lorraine Kimsa Theatre for Young People, Toronto. The Adventures of Ali & Ali and the aXes of Evil 2003-07 by Youssef, Verdecchia, and Chai. Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton, Victoria, Seattle. Cahoots Theatre Projects 1999 – 2004 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. Responsible for artistic planning and activities for company dedicated to development and production of new plays representative of Canada's cultural diversity. -

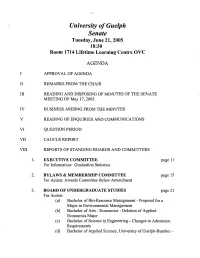

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

The Black Drum Deaf Culture Centre Adam Pottle

THE BLACK DRUM DEAF CULTURE CENTRE ADAM POTTLE ApproximatE Running time: 1 HouR 30 minutEs INcLudes interviews before the performancE and During intermissIoN. A NOTE FROM JOANNE CRIPPS A NOTE FROM MIRA ZUCKERMANN With our focus on oppression, we forget First of all, I would like to thank the DEAF to celebrate Deaf Life. We celebrate Deaf CULTURE CENTRE for bringing me on as Life through sign language, culture and Director of The Black Drum, thereby giving arts. The Black Drum is a full exploration me the opportunity to work with a new and and celebration of our Deaf Canadian exciting international project. The project experience through our unique artistic is a completely new way of approaching practices finally brought together into one musical theatre, and it made me wonder exceptional large scale signed musical. - what do Deaf people define as music? All Almost never do we see Deaf productions Deaf people have music within them, but it that are Deaf led for a fully Deaf authentic is not based on sound. It is based on sight, innovative artistic experience in Canada. and more importantly, sign language. As We can celebrate sign language and Deaf we say - “my hands are my language, my generated arts by Deaf performers for all eyes are my ears”. I gladly accepted the audiences to enjoy together. We hope you invitation to come to Toronto, embarking have a fascinating adventure that you will on an exciting and challenging project that not easily forget and that sets the stage for I hope you all enjoy! more Deaf-led productions. -

Manor Park Chronicle Jan 2019

The voice of the community for 70 years • January 2019 • Vol. 70, No. 3 Arundel Ave., fall 1947: A sea of mud and construction in Manor Park Village. Photo: Newton (Ottawa Journal) Getting to Manor Park: A city bus plows through the mud of St. Laurent Blvd. Photo: Archives, City of Ottawa A Publishing Milestone: 70 years and counting! January 1949 – January 2019 By Sharleen Tattersfield steadily expanding ‘village’, can lend a helping hand in spaced, frame houses that were sion to use the garage Manor Park was a community making Manor Park one vulnerable to the spread of fire: portion of the tempo- This January 2019 issue of of homes still under construc- of the finest villages in our “Three brigades were or- rary school [in General the Manor Park Chronicle tion; muddy, unpaved roads; country.” ganized consisting of ten Mann’s stables, where St. marks the 70th publishing an- no sidewalks, street signs or men each. All individuals Columba Church is today) niversary of our community lights; no mail or bus service, The first page of the Janu- approached were will- as a fire hall. The Manor newspaper. The first issue, and a temporary school. ary 1949 Chronicle featured a ing to assume responsi- Park Ratepayers Associa- Volume 1, # 1 (a news sheet) report by the executive of the bilities. Representatives tion Executive is provid- was produced in January The inaugural issue Manor Park Ratepayers Asso- of the Committee met ing financial assistance.” 1949 and “edited by J. Wil- That inaugural issue was a ciation on much-needed com- with the Gloucester Twp.