An Introductory Guide to Vibraphone: Four Idiomatic Practices and a Survey of Pedagogical Material and Solo Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Documents and Settings\Jeff Snyder.WITOLD\My Documents

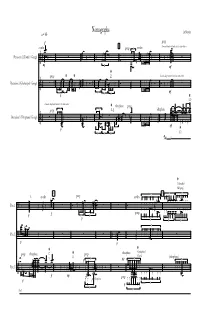

Nomographs q = 66 Jeff Snyder gongs 5 crotalesf gongs crotales diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters 5 Percussion 1 (Crotales / Gongs) 5 P F D diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters gongs _ Percussion 2 (Glockenspiel / Gongs) 3 3 5 5 5 F p G diamond-shaped noteheads indicate rattan beaters 5 vibraphone gongs gongs 3 D, A_ vibraphone Percussion 3 (Vibraphone / Gongs) 5 F p 5 5 5 E A (crotales) A# (gong) 10 7 15 7 7 l.v. crotales gongs crotales Perc.1 gongs 5 5 f p p 7 7 7 7 Perc.2 p p A (vibraphone) gongs vibraphone C gongs vibraphone G E (gong) (vibraphone) 5 7 7 p pp Perc.3 gongs f P vibraphone p 7 p 5 (Ped.) p 7 2 (rattan on both side (damp all) A (crotales) 20 5 5 3 and center of gong) gongs 3 Perc.1 3 3 f (rattan on both side (l.v.) C# and center of gong) 3 3 3 3 3 3 Perc.2 vibraphone D (vibraphone) F vibraphone (damp all) 3 D# (gong) gong vibraphone C# gongs (vibraphone) Perc.3 3 3 5 5 gongs 3 5 25 crotales 5 30 B (rattan on side) (all) gongs 3 Perc.1 5 (rattan on both side 5 5 gongs 5 p 5 5 5 f (rattan on side) and center of gong) (all) -

74TH SEASON of CONCERTS April 24, 2016 • National Gallery of Art PROGRAM

74TH SEASON OF CONCERTS april 24, 2016 • national gallery of art PROGRAM 3:30 • West Building, West Garden Court Inscape Richard Scerbo, conductor Toru Takemitsu (1930 – 1996) Rain Spell Asha Srinivasan (b. 1980) Svara-Lila John Harbison (b. 1938) Mirabai Songs It’s True, I Went to the Market All I Was Doing Was Breathing Why Mira Can’t Go Back to Her Old House Where Did You Go? The Clouds Don’t Go, Don’t Go Monica Soto-Gil, mezzo soprano Intermission Chen Yi (b. 1953) Wu Yu Praying for Rain Shifan Gong-and-Drum Toru Takemitsu Archipelago S. 2 • National Gallery of Art The Musicians Founded in 2004 by artistic director Richard Scerbo, Inscape Chamber Orchestra is pushing the boundaries of classical music in riveting performances that reach across genres and generations and transcend the confines of the traditional concert experience. With its flexible roster and unique brand of programming, this Grammy-nominated group of high-energy master musicians has quickly established itself as one of the premier performing ensembles in the Washington, DC, region and beyond. Inscape has worked with emerging American composers and has a commitment to presenting concerts featuring the music of our time. Since its inception, the group has commissioned and premiered over twenty new works. Its members regularly perform with the National, Baltimore, Philadel- phia, Virginia, Richmond, and Delaware symphonies and the Washington Opera Orchestra; they are members of the Washington service bands. Inscape’s roots can be traced to the University of Maryland School of Music, when Scerbo and other music students collaborated at the Clarice Smith Center as the Philharmonia Ensemble. -

The 2021 Ohio Governor's Youth Art Exhibition

SPONSORS • AMACO/ Brent • Art Academy of Cincinnati • Ashland University • Blick Art Materials • Bowling Green State University, School of Art • Buckeye Ceramic Supply • Cleveland Institute of Art • College for Creative Studies - Detroit, MI • Columbus Clay Company • Columbus College of Art and Design • Kansas City Art Institute (KCAI) - Kansas City, MO • Kendall College of Art and Design of Ferris State University - Grand Rapids, MI • Laguna College of Art and Design - Laguna Beach, CA • Mansfield Art Center • Mayco Colors • Maryland Institute, College of Art - Baltimore, MD • McConnell Arts Center of Worthington • Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design (MIAD) • The Modern College of Design - Kettering, OH • Mount St. Joseph University - Cincinnati, OH • Myers School of Art, The University of Akron • Ohio Art Education Association • Ohio Ceramic Supply • Ohio Designer Craftsmen • Ohio Northern University - Ada, OH • Ohio State Fair Youth Arts Exhibition • Ohio University, School of Art + Design - Athens, OH • Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) • School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) • School of Visual Arts (SVA) - New York, NY • Support for Talented Students, Inc. (STS) • University of Dayton Online Exhibition Opens • University of St. Francis, School of Creative Arts - Ft. Wayne, IN Sunday April 25, 2021 • University of Toledo Department of Art at www.govart.org • Wright State University - Dayton, OH • The Governor of the State of Ohio • The Ohio Department of Education 2021 Top 25 Award of Excellence The 2021 Ohio Governor’s Youth Art Exhibition April 25 through May 21, 2021 Virtual Exhibition and Awards are available for viewing at www.govart.org The Exhibition • is a non-profit organization established in 1970 to promote the arts and to reward the youth of Ohio for their achievements in the visual arts. -

Contemporary Music Ensemble

Suffolk County Community College • Music Department • Ammerman Campus Presents Contemporary Music Ensemble Spring Concert May 12, 2001 7:30 pm Islip Arts Building, Shea Theatre Contemporary Music Ensemble William Ryan, Director ________________________________________________ Premonition (1997) Phil Kline for many boomboxes (b. 1953) Vanessa Bonet Malachy Gately Lauren Kohler Jamie Carrillo David Greenberg Anne McInerney Lisa Casal Duane Haynes Corin Misiano Chris Ciccone Ryan Himpler Michelle Orabona Mike Clark William Jantz Rachel Rodgers Anne Dekenipp Colin Kasprowicz Gerry Rulon-Maxwell Virginia Dimiceli Andrew Keegan Michael Sarling Jason Dobranski Melanie Scalice Jessica Drozd Pete Stumme Joe Fogarazzo Naomi Volkel New York Counterpoint (1985) Steve Reich for clarinet and tape (b. 1936) Joseph Iannetto, clarinet Evan Ziporyn, recorded clarinets Elvis Everywhere (1987) Michael Daugherty for string quartet and tape (b. 1954) Lisa Casal, violin Malachy Gately, violin Vanessa Bonet, viola Jason Dobranski, cello A Change of Hearts (2001) Phil Kline for chamber ensemble and boomboxes (b. 1953) World Premiere Commissioned by the SCCC Contemporary Music Ensemble Melanie Scalice, flute Joseph Iannetto, clarinet Lauren Kohler, clarinet David Greenberg, trumpet Lisa Casal, violin Malachy Gately, violin Vanessa Bonet, viola Jamie Carrillo, viola Jason Dobranski, cello Colin Kasprowicz, keyboard Rachel Rodgers, electric bass Joe Fogarazzo, electric guitar Gerry Rulon-Maxwell, guitar Program Notes Premonition was written as a fanfare for the Bang On A Can Festival’s 10th Birthday Party. It is scored for an imaginary orchestra of 1000 strings or, (let’s get this right,) a real orchestra of 1000 virtual (computer- midi) strings. -Phil Kline New York Counterpoint is one of a series of works for soloist accompanied by pre-recorded layers of themselves. -

The PAS Educators' Companion

The PAS Educators’ Companion A Helpful Resource of the PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Volume VIII Fall 2020 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 EDUCATORS’ COMPANION THE PAS EDUCATORS’ COMPANION PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE ARTICLE AUTHORS DAVE GERHART YAMAHA CORPORATION OF AMERICA ERIK FORST MESSIAH UNIVERSITY JOSHUA KNIGHT MISSOURI WESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY MATHEW BLACK CARMEL HIGH SCHOOL MATT MOORE V.R. EATON HIGH SCHOOL MICHAEL HUESTIS PROSPER HIGH SCHOOL SCOTT BROWN DICKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL AND WALTON HIGH SCHOOL STEVE GRAVES LEXINGTON JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL JESSICA WILLIAMS ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY EMILY TANNERT PATTERSON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS How to reach the Percussive Arts Society: VOICE 317.974.4488 FAX 317.974.4499 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB www.pas.org HOURS Monday–Friday, 9 A.M.–5 P.M. EST PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM 3 by Dr. Dave Gerhart CONSISTENCY MATTERS: Developing a Shared Vernacular for Beginning 6 Percussion and Wind Students in a Heterogeneous Classroom by Dr. Erik M. Forst PERFECT PART ASSIGNMENTS - ACHIEVING THE IMPOSSIBLE 10 by Dr. Joshua J. Knight TOOLS TO KEEP STUDENTS INTRIGUED AND MOTIVATED WHILE PRACTICING 15 FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS by Matthew Black BEGINNER MALLET READING: DEVELOPING A CURRICULUM THAT COVERS 17 THE BASES by Matt Moore ACCESSORIES 26 by Michael Huestis ISOLATING SKILL SETS, TECHNIQUES, AND CONCEPTS WITH 30 BEGINNING PERCUSSION by Scott Brown INCORPORATING PERCUSSION FUNDAMENTALS IN FULL BAND REHEARSAL 33 by Steve Graves YOUR YOUNG PERCUSSIONISTS CRAVE ATTENTION: Advice and Tips on 39 Instructing Young Percussionists by Jessica Williams TEN TIPS FOR FABULOUS SNARE DRUM FUNDAMENTALS 46 by Emily Tannert Patterson ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 49 2 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATORS’ COMPANION BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM by Dr. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

![1867-12-18, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5874/1867-12-18-p-315874.webp)

1867-12-18, [P ]

Home and Other Itema. Saw, you and Doc. make a good team Mews and Item*. i take part in it Ole Bull, the world- 'fh* Dlckriu. | Those irreverent lads who called names W. \V. Bornartl, of<j<ranper,Minn., call Jhc limes. The Commonwealth Ins. Co. is a new and Both Houses will ndjonrn on the ?0th renowned Norwegian violinist, arrived in New York 1ms fairly Out-Bostoned Bos after a certain "bald head"' of old, deserv* Hotel Loo£*l ed to see as last week on liis wny east.— 1 THERE IS A NKWLY FINISHED llOTlt A# | strong institution established in Decorah.1 iirst., until the 6th of January One J New York last week, en route for Chicago, ton in the Dickens excitement. The sale ed their untimely end, because nt thnt time When he returns we will say he is a pret of tickets for the Dickens readings com no panacea had been discovered to restore X.I 3VI E 8PRINO8, McOHEOUK, DEC. 18, 1867 Is that young and thriving city to be the week ago the street cars of New York was where he is expected to arrive some time ty good man, if he will permit it. We are menced at Steinwav Ilall at nine o'clock the human Iiair upon the bald spots. But Oi* nit McOreook Rahwit, INHtMy. Insurance center of the whole west? Suo blockaded with snow The Chicago Dai-1 this week The commissioner of pen- this morning, and lon^ before the hour a now, Ring's Vegetable Ambrosia is known •ltvar? trliid to *te the Chesterfield Mer- That wants to be sold lor eauh or exchanged for a' . -

Shadow of the Sun for Large Orchestra

Shadow of the Sun for Large Orchestra A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Department of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Hojin Lee M.F.A. University of California, Irvine November 2019 Committee Chair: Douglas Knehans, D.M.A. Abstract It was a quite astonishing moment of watching total solar eclipse in 2017. Two opposite universal images have been merged and passed by each other. It was exciting to watch and inspired me to write a piece about that image ii All rights are reserved by Hojin Lee, 2018 iii Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents iv Cover page 1 Program note 2 Instrumentation 3 Shadow of the Sun 4 Bibliography 86 iv The Shadow of the Sun (2018) Hojin Lee Program Note It was a quite astonishing moment of watching total solar eclipse in 2017. Two opposite universal images have been merged and passed by each other. It was very exciting to watch and inspired me to write a piece about that image. Instrumentation Flute 1 Flute 2 (Doubling Piccolo 2) Flute 3 (Doubling Piccolo 1) Oboe 1 Oboe2 English Horn Eb Clarinet Bb Clarinet 1 Bb Clarinet 2 Bass Clarinet Bassoon 1 Bassoon 2 Contra Bassoon 6 French Horns 4 Trumpets 2 Trombones 1 Bass Trombone 1 Tuba Timpani : 32” 28” 25” 21” 4 Percussions: Percussion 1: Glockenspiel, Vibraphone, Crotales (Two Octaves) Percussion 2: Xylophone, Triangle, Marimba, Suspended Cymbals Percussion 3: Triangle, Vibraphone, -

An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition

Illuminating Silent Voices: An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition by Darrell Irwin Thompson A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Mark Sunkett, Chair Bliss Little Kay Norton James DeMars Jeffrey Bush ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2012 ABSTRACT Illuminating Silent Voices: An African-American Contribution to the Percussion Literature in the Western Art Music Tradition will discuss how Raymond Ridley's original composition, FyrStar (2009), is comparable to other pre-existing percussion works in the literature. Selected compositions for comparison included Darius Milhaud's Concerto for Marimba, Vibraphone and Orchestra, Op. 278 (1949); David Friedman's and Dave Samuels's Carousel (1985); Raymond Helble's Duo Concertante for Vibraphone and Marimba, Op. 54 (2009); Tera de Marez Oyens's Octopus: for Bass Clarinet and one Percussionist (marimba/vibraphone) (1982). In the course of this document, the author will discuss the uniqueness of FyrStar's instrumentation of nine single reed instruments--E-flat clarinet, B-flat clarinet, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, B-flat contrabass clarinet, B-flat soprano saxophone, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, and B-flat baritone saxophone, juxtaposing this unique instrumentation to the symbolic relationship between the ensemble, marimba, and vibraphone. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I first want to thank God, for guiding my thoughts, hands, and feet. I am grateful, for the support, understanding, and guidance I have received from my parents. I also want to thank my grandmother, sister, brother, and to the rest of my family for being one of the best support groups anyone could have. -

José Lerma B

José Lerma b. 1971, Seville, Spain Lives and works in Chicago, IL, and San Juan, Puerto Rico EDUCATION 2003 CORE Residency Program, Glassell School, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX 2003 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME Fortaleza 302 Residency Program, San Juan, Puerto Rico 2002 MFA, MA, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 1995 University of Wisconsin Law School, Madison, WI 1994 BA, Political Science, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA COLLECTIONS Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY Saatchi Collection, London, UK Museum of Fine Arts Houston, TX Milwaukee Art Museum, WI Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, WI Arario Collection, Seoul, South Korea Aby Rosen, New York, NY Phillip Isles, New York, NY Dakkis Joannou, Athens, Greece Fidelity Investments, NY Colección VAC, Valencia, Spain A. De la Cruz Collection, Puerto Rico Phillara Collection, Düsseldorf, Germany Colección Berezdivin, Santurce, Puerto Rico Colección Cesar y Mima Reyes, San Juan, Puerto Rico SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 José Lerma, Galería Leyendecker, Islas Canarias, Spain 2018 José Lerma – Io e Io, Diablo Rosso, Panama City, Republic of Panama 2017 Nunquam Prandium Liberum, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL The Last Upper, Brand New Gallery, Milan, Italy 2016 José Lerma: La Venida Cansa Sin Ti, Kemper Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, San Juan, Puerto Rico Huevolution, Halsey McKay Gallery, East Hampton, NY Josh Reames & Jose Lerma, Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 2014 La Bella Crisis, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, -

Thesis- Pedagogical Concepts for Marching Percussion

PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS 1 Running head: PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS FOR MARCHING PERCUSSION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC EDUCATION: STUDIO PEDAGOGY EMPHASIS THOMAS JOHN FORD UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-STEVENS POINT MAY, 2019 PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS 2 Abstract This document serves as a guide for recent music education graduates who are put in the position of having to teach marching percussion to students who have joined the marching band, specifically in the drumline. To have a well-rounded understanding of the drumline, teachers will need to know the instruments of the drumline, and the associated sticks and mallets. This document also discusses pedagogical concepts for all of the instruments, including playing techniques required to achieve a balanced sound throughout the ensemble, and how to properly care for marching percussion equipment. Keywords: marching percussion, drumline, battery, snare drums, tenor drums, bass drums, crash cymbals PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS 3 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 5 List of Figures 8 Introduction 9 Chapter I: Marching Percussion Equipment 12 Snare Drums 12 Tenor Drums 14 Bass Drums 16 Crash Cymbals 17 Other Equipment 18 Chapter II: Pedagogical Concepts for Marching Percussion 21 Posture 21 Playing Positions 21 Grips and General Playing Techniques 25 Stroke Types and Dynamics 31 The Exercise and Technical Development Program 32 Timing Strategies 37 Chapter III: Marching Percussion Care and Maintenance 39 Changing and Replacing Heads 39 Repairing Broken and Loose Drum Equipment 40 Cymbal Straps 42 Cleaning and Storing Equipment 43 PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS 4 Conclusion 45 References 46 Appendix A 49 PEDAGOGICAL CONCEPTS 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are so many people who I want and am obligated to thank for helping me in this whole process of graduate school and writing my thesis.