Clinical Outcomes of Socket Preservation Using Bovine-Derived

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socket Preservation: Allograft Vs. Alloplast

ytology & f C H i o s l t a o n l o r g u y o J Sezavar, et al., J Cytol Histol 2015, S3:1 Journal of Cytology & Histology DOI: 10.4172/2157-7099.S3-009 ISSN: 2157-7099 Research Article Open Access Socket Preservation: Allograft vs. Alloplast Mehdi Sezavar1, Behnam Bohlouli1, Mohammad Hosein Kalantar Motamedi1*, Jahanfar Jahanbani2 and Masoud Shah Hosseini3 1OMFS Department, Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tehran Dental branch, IR Iran 2Department of pathology, Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tehran Dental branch, IR Iran 3Dental student, Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tehran Dental branch, IR Iran *Corresponding author: Motamedi MHK, OMFS Department, Azad University of Medical Sciences, Tehran Dental branch, Iran, Tel: 98- 9121937154; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Apr 09, 2015, Acc date: Apr 21, 2015, Pub date: Apr 23, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Sezavar M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Background: The volume shrinkage of the alveolar ridge might be minimized by the ridge preservation stages and applied biomaterials, after tooth extraction. Objectives: The aim of this study is to compare alloplastic with allograft in terms of preservation and bone regeneration of the alveolar ridge after tooth extraction. Materials and Methods: This study clinically assessed this issue via the Split Mouth method which assessed 10 dental sockets filled with alloplasts and 9 others with allografts postextraction. The effectiveness of each material was clinically and histologically processed. -

Ridge Preservation in a Case of Severe Periodontitis

CONTINUING EDUCATION Ridge preservation in a case of severe periodontitis Drs. Roberto Rossi, Ulf Nannmark, Andrea Pilloni, and Nino Squadrito, CDT, demonstrate how to preserve and condition the soft tissue with a combined approach eriodontal disease is often responsible for Pthe loss of attachment around teeth and Educational aims and objectives therefore a major cause of ridge deficiency This article aims to present a case of advanced periodontitis treated with implants and after the teeth are extracted. The world has a ridge preservation technique to help preserve and improve the soft tissue. become more and more aware of esthetics in dentistry, and any procedure aimed to Expected outcomes Implant Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions on page XX to preserve the hard and soft tissue becomes earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will useful to satisfy the needs of increasingly demonstrate the reader can: demanding patients. • Identify a technique for approaching implant treatment in severe periodontitis This article will present a case of in order to minimize the collapse of the soft and hard tissue and thus try to preserve the natural esthetics. advanced periodontitis treated with a ridge • Review the biology of tooth extractions, wound healing, and residual ridge modeling. preservation technique and later planned • See how this technique with the materials used limited contour changes after tooth extraction and and finalized with the use of guided implant preserved facial keratinized gingiva. surgery, immediate loading, and thus, soft • Realize the differences in the pattern of bone resorption in periodontitis and non-periodontitis subjects. -

Problem Solvers 31 Socket Grafting Synonyms: Socket Preservation, Grafting, Socket Grafting, Augmentation

Problem Solvers 31 Socket Grafting Synonyms: socket preservation, grafting, socket grafting, augmentation. Twenty million teeth are removed each year in the United States. The ability to replace this missing tooth with dental implants has never been more predictable if attention is paid to preserving the existing bone around the tooth socket. This procedure is called socket grafting or socket preservation. Tooth loss can be very traumatic. Millions of people lose a tooth and are never told about the bad things that happen if the tooth is lost. In the first six months after a tooth is pulled a person can lose 40% of the remaining bone height and 60% of the bone width where the tooth was. This can lead to severe difficulties cosmetically and functionally when trying to restore the missing tooth with a dental implant. When teeth are lost the teeth on each side of the space can drift into the space. This can change someone’s bite and lead to further shifting and fracture of the surrounding teeth. The next problem is super‐eruption. This is when the tooth directly opposite of the pulled tooth will move into the space left by this extraction. This can lead to painful biting on your own skin or uneven bites, which can result in fracture. As well, if there is super‐eruption, then there is not enough space left to replace the missing tooth with a bridge or an implant. This can mean that the tooth that has super‐ erupted must have a crown to shorten the tooth, or orthodontics to intrude or put the tooth back into its normal position. -

Socket Preservation Techniques

CLINICAL Simple & Predictable Socket Preservation Techniques All Dentists Can Implement Regardless of Extraction or Grafting Experience by Timothy Kosinski, DDS, MAGD Affiliate Adjunct Clinical Professor, University of Detroit Mercy School of Dentistry “Simple” socket grafting following an atraumatic extraction has become an integral part of general dental treatment and hether you are grafting or should be offered to our patients to prevent bone resorption. not already in your practice, Following extraction of a non restorable tooth, the remaining socket heals from the apex toward the crest. When nothing is Wthis article will demonstrate placed into the socket at the time of the extraction, the soft a simple socket preservation technique tissue infiltration at the crest often results in facial and crestal all dentists can easily implement as a bone loss. This will often impede ideal dental implant placement in the future or will require more invasive grafting procedures service offering following an atraumatic in the future which is a secondary surgery for the patient that extraction. This provides a great service could have been prevented. Maxillary posterior tooth roots hold to your patients and allows for your graft up the sinus floor like a tent pole holding up a circus tent. When the tent poles are removed, the tent will collapse. The same procedures to be more profitable – as occurs in the maxillary sinus area. When roots are removed the well as predictable. Regardless of your sinus may collapse unless maintained with grafting materials. extraction and grafting experience, Therefore, socket grafting of extraction sites should by utilizing the techniques outlined become a routine procedure for the dentist - even if you just through this clinical case, I am confident start with and offer the simple socket preservation techniques outlined in this article. -

The Preservation of Alveolar Bone Ridge During Tooth Extraction Marius Kubilius, Ricardas Kubilius, Alvydas Gleiznys

REVIEWS SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES Stomatologija, Baltic Dental and Maxillofacial Journal, 14: 3-11, 2012 The preservation of alveolar bone ridge during tooth extraction Marius Kubilius, Ricardas Kubilius, Alvydas Gleiznys SUMMARY Objectives. The aims were to overview healing of extraction socket, recommendations for atraumatic tooth extraction, possibilities of post extraction socket bone and soft tissues preservation, augmentation. Materials and Methods. A search was done in Pubmed on key words in English from 1962 to December 2011. Additionally, last decades different scientifi c publications, books from ref- erence list were assessed for appropriate review if relevant. Results and conclusions. There was made intraalveolar and extraalveolar postextractional socket healing overview. There was established the importance and effectiveness of atraumatic tooth extraction and subsequent postextractional socket augmentation in limited hard and soft tissue defects. There are many different methods, techniques, periods, materials in regard to the review. It is diffi cult to compare the data and to give the priority to one. Key words: tooth extraction, grafting, socket, healing, ridge preservation. INTRODUCTION Nowadays tooth extraction becomes more im- portunity to get acknowledge with summarized con- portant in complex odontological treatment. Three temporary scientifi c publication results, methodologies dimensional bones’ and soft tissue parameters infl u- and practical recommendations in preserving alveolar ence further treatment plan, results and long time crest in tooth extraction (validity for atraumatic tooth prognosis. Tooth extraction inevitably has infl uence extraction, operative methods, protection of alveolus in bone resorption and changes in gingival contours. after extractions, feasible post extraction fi llers and Further treatment may become more complex in using complications, alternative treatment). -

A String of Pearls

Comprehensive Oral Rehabilitation & Esthetic Dentistry presents A String of Pearls Jeffrey S. Rouse, DDS William J. Robbins, DDS, MA [email protected] [email protected] 210.828.3334 210.341.4409 coredentistry.com © 2007 CORE Dentistry SUBJECTS: “The Gummy Smile” 1. Upper Lip Short/Hyperactive Lip Dentoalveolar Extrusion 1. Upper Lip - Short Behavior Modification Orthodontic Intrusion - Short - Hyperactive Surgery Functional Crown Lengthening - Hyperactive 2. Short Clinical Crown Botox? Full Mouth Rehabilitation 2. Short Clinical Crown - Normal Variation Vertical Maxillary Excess - Normal Variation - Incisal Wear Altered Passive Eruption Maxillary Le Forte 1 Impaction - Incisal Wear - Altered Passive Eruption Esthetic Crown Lengthening - Altered Passive Eruption 3. Dentoalveolar Extrusion Sulcular Incision 3. Dentoalveolar Extrusion 4. Vertical Maxillary Excess Internal Bevel Gingivectomy 4. Vertical Maxillary Excess 5. Combination 5. Combination Differential Diagnosis 1. Short or Hyperactive Upper Lip 3. Dentoalveolar Extrusion - Normal length: Young Female 20-22mm - Diagnosis: Concave gingival line Young Male 22-24 mm - Normal Activity: 6-8mm 4. Vertical Maxillary Excess - Diagnosis: Lower 1/3 of face is 2. Short Clinical Crown due to Altered Passive Eruption longer than middle 1/3 - Diagnosis: Short tooth and cannot feel CEJ in sulcus SUBJECTS: CORE Esthetic Evaluation Photography: Print, Slide, and Digital Dental-Facial Midline Determining the Incisal Edge Position of the Centrals Diagnostic Records: Centrals Exposed in Repose Posterior Occlusal Plane Facebow Distal Extent of the Smile Tooth Length and Width DentoFacial Analyser Buccal Corridors CEJs Located Centric Relation Registration Incisal Edges to Lower Lip Incisal Wear Face Height Gingival Architecture Tooth Alignment and Color Incisal Edge Position Upper Lip Line Spacing Overlap, and Diastema Lip Length Angle of Incisal Plane- Maxillary and Mandibular Lip Mobility Incisal edge position based on esthetics, phonetics, 4. -

Orthodontic Socket Preservation (O.S.P.) Massimo D’Aversa1*, Dr

Oral Health and Care Research Article ISSN: 2399-9640 Orthodontic Socket Preservation (O.S.P.) Massimo D’Aversa1*, Dr. ssa Monica Macrì2 and Felice Festa2 1Dental Surgery, Private practice in oral surgery and orthodontics Via Guazzatore 4 60027 Osimo, Italy 2Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Medicine “G. D’Annunzio” Chieti Pescara, Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Orali e Biotecnologie Via dei Vestini 31, 66100 Chieti Scalo, Italy Introduction Socket preservation has shown to be a very valuable adjunct procedure in implant dentistry. Preserving labial cortical bone during tooth extraction is mandatory to obtain a wider alveolar bone leading to a long-term stability of dental implants [1-8]. Several dental malocclusions, regardless of the improvement of orthodontic therapy in the last years, can still benefit from dental extractions. Severe crowding, thin periodontal tissues and dental protrusion are common conditions that can lead to teeth extractions for orthodontic treatment success [9-11]. (Figure 1) Oral surgery standard extraction procedures have always advocated Figure 2. Labial position of teeth in the alveolar bone from CBCT scans and from human that, due to the labial position of the dentition in the alveolar bone, any skulls. Labial cortical bone is always less represented compared to the lingual or palatal tooth should be extracted following a pathway towards the thin buccal bone cortical bone, because lingual or palatal cortical bone is always wider The purpose of this paper is to show how a modified extraction and harder to allow root dislocation during an extraction procedure technique focused in preserving the alveolar socket can improve [9]. (Figure 2) tooth movement during space closure and can result in a healthier Dislocation, iatrogenic disruption or removal of the labial cortical periodontum at the end of the treatment. -

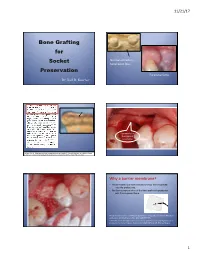

Bone Grafting for Socket Preservation

11/21/17 Bone Grafting for Normal extraction Socket facial bone loss. Preservation Excessive force. Dr. Karl R. Koerner Commonly the thickness of facial bone. Hussain, A. et al. Ridge preservation comparing a nonresorbable PTFE membrane to a resorbable collagen membrane: a clinical and histologic study in humans. Implant Dentistry. 25(1):128-134, 2016. Why a barrier membrane? • Prevent epithelium and connective tissue from migrating into the grafted site, • Facilitating repopulation of the bone graft with progenitor cells from adjacent bone. Retzepi M and Donos N. Guided bone regeneration: Biological principle and therapeutic applications. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010:21(6):567-576. Greenstein, et al. Utilization of d-PTFE barriers for post-extraction bone regeneration in preparation for dental implants. Compendium 2015:36(7), pp.465-472. July/August. 1 11/21/17 How long does it take a bone How can socket grafts fail?? graft to not need • Bone graft material comes out. protection any more… – No membrane. – Inadequate membrane. to not need a barrier – Closure opens up after surgery. membrane any more… – Membrane lost from patient non-compliance. • Stays in but is contaminated and does not to become “osteoid”? become “osteoid”. Stays particulate. • Disappears or loses volume from lack of nutrients, inadequate blood supply. Minimum 3-4 weeks. The problem. Part of the solution. 1. 2 week post-op. Too many choices for socket grafts? • BioGide, Ossix Plus • BioGide, Ossix Plus, • Cytoplast (PTFE) • BioXclude other collagens… • Epiguide • Cytoplast (PTFE) 1 month post-op. • Laminar bone • Osteogen Plugs • BioXclude If nearly closed (within 3-4 mm) • Epiguide can use collagen membrane. -

Autologous Tooth Graft After Endodontical Treated Used for Socket Preservation: a Multicenter Clinical Study

applied sciences Article Autologous Tooth Graft after Endodontical Treated Used for Socket Preservation: A Multicenter Clinical Study Elio Minetti 1,2,* , Andrea Palermo 1,3,4, Franco Ferrante 4 , Johannes H. Schmitz 2, Henry Kim Lung Ho 5, Simon Ng. Dih Hann 5,6, Edoardo Giacometti 7,8, Ugo Gambardella 9, Marcello Contessi 10, Martin Celko 9,11, Andrea Ballini 12 , Carmen Mortellaro 13, Paolo Trisi 14 and Filiberto Mastrangelo 13,15,* 1 University of Bari Aldo Moro, 70121 Bari, Italy; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Private Practice, 20100 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 3 College of Medicine and Dentistry Birmingham, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK 4 Private Practice, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] 5 Private practice, Singapore 238863; [email protected] (H.K.L.H.); [email protected] (S.N.D.H.) 6 University of Naples Federico II, 80100 Naples, Italy 7 Visiting Professor University of Genoa, 16126 Genova, Italy; [email protected] 8 Private Practice, 10121 Turin, Italy 9 Private Practice, 50002 Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic; [email protected] (U.G.); [email protected] (M.C.) 10 Private Practice, 34121 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] 11 Olomouc University, 77147 Olomouc, Czech Republic 12 School of Medicine, University of Bari, 70121 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 13 School of Dentistry, University of Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] 14 Private Practice - Biomaterial Clinical and Histological Research Association; [email protected] 15 Clinical and Experimental Medicine Dept. School of Dentistry University of Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.M.); fi[email protected] or fi[email protected] (F.M.) Received: 22 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 10 December 2019 Abstract: The aim of the study was to evaluate the tooth extracted use as autologous tooth graft after endodontic root canal therapies used for socket preservation. -

Tooth Extraction—An Opportunity for Site Preservation

IMPLANT DENTISTRY Tooth Extraction—An Opportunity for Site Preservation or a patient, the loss of a tooth flat basilar bone.9-11 induces not only emotional Alveolar bone survives only in the Ftrauma but also physical presence of dentition. The existence deformity. Removal spurs bone of intact teeth in a partially edentu- resorption, which increases over lous ridge defies or at least delays the time. As the soft-tissue drape follows sort of severe loss reported above Michael Sonick, DMD the osseous contour, such remodel- because the bone remains to support Director of Sonick Seminars ing may result in a depressed mucos- them; this is the concept fundamental Private Practice 8 Periodontics and Implant Dentistry al profile, especially if a thin biotype to the use of overdentures. Despite Fairfield, Connecticut exists. This becomes a possible visu- adjacent teeth, some level of resorp- Phone: 203.254.2006 al concern. Immediately after extrac- tion occurs after the removal of 1 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.sonickdmd.com tion, the socket walls undergo inter- tooth, depending on a host of factors. nal and external turnover, resulting These influencing variables include: Board Member Contemporary Esthetics in crestal bone loss as well as hori- • Anatomy. A thicker, wider ridge zontal reduction. Buccolingual loss tends to resorb less, possibly overall exceeds that in the vertical because of higher vascularity. As it direction, though both occur. Several is typically thinner, the buccal wall investigations report horizontal and diminishes more than the lingual vertical deficits of 3.0 mm to 6.0 mm 2 to 4 months after tooth removal. -

Consent for Extraction/Socket Preservation Bone Grafting

7384 S. Alton Way, Suite 101, Centennial, CO 80112 │ p 303.721.1173 │ f 303.721.1179 │ www.denver-perio.com Consent for extraction/socket preservation bone grafting Recommended Treatment: Heather Richardson DMD MS has recommended that a tooth or several teeth be extracted (pulled). Local anesthetic will be administered as part of doing the extraction. Bone grafting will be done to preserve the bone contour. Principal Risks and Complications: Complications that may result from surgery could involve the surgery procedure, bone regenerative materials, drugs, or anesthetics. These complications include, but are not limited to post-surgical infection, bleeding, swelling, pain, facial bruising, jaw joint pain or muscle spasm, sinus infection, cracking or bruising of the corners of the mouth, restricted ability to open the mouth for several days or weeks, impact on speech, allergic reactions, accidental swallowing of foreign matter, and transient (on rarest of occasions permanent) increased tooth looseness, tooth sensitivity to hot, cold, sweet or acidic foods, and transient (on rare occasions permanent) numbness of the jaw, lip, tongue, chin or gums. A dry socket can cause pain for about a week. Extracted teeth that are not replaced may lead to the other teeth moving or drifting, creating spaces between the remaining teeth and making it difficult to impossible to replace them or straighten them later. The exact duration of any complication cannot be determined, and they may be irreversible Alternatives to suggested Treatment: 1. No extraction(s). 2. Extraction without grafting Necessary Follow-up Care and Self-Care: It is important for me to continue to see my regular dentist for routine dental care and to get the missing tooth/teeth replaced as recommended. -

Alveolar Socket Preservation with Demineralised Bovine Bone Mineral and a Collagen Matrix

J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2017 Aug;47(4):194-210 https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2017.47.4.194 pISSN 2093-2278·eISSN 2093-2286 Research Article Alveolar socket preservation with demineralised bovine bone mineral and a collagen matrix Carlo Maiorana 1, Pier Paolo Poli 1,*, Matteo Deflorian 2, Tiziano Testori 2, Federico Mandelli 3, Heiner Nagursky 4, Raffaele Vinci 3 1Implant Center for Edentulism and Jawbone Atrophies, Maxillofacial Surgery and Odontostomatology Unit, IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Foundation, University of Milan, Milan, Italy 2Section of Implant Dentistry and Oral Rehabilitation, Department of Biomedical, Surgical and Dental Sciences, Dental Clinic, IRCCS Galeazzi Orthopedic Institute, University of Milan, Milan, Italy 3Dental School, Vita-Salute University and Department of Dentistry, IRCCS San Raffaele Hospital, Milan, Italy 4Medical Center, University of Freiburg Institute for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, Freiburg, Germany Received: May 16, 2017 ABSTRACT Accepted: Jul 10, 2017 *Correspondence: Purpose: The aim of the present study was to evaluate the healing of post-extraction sockets Pier Paolo Poli following alveolar ridge preservation clinically, radiologically, and histologically. Implant Center for Edentulism and Jawbone Methods: Overall, 7 extraction sockets in 7 patients were grafted with demineralised bovine Atrophies, Maxillofacial Surgery and bone mineral and covered with a porcine-derived non-crosslinked collagen matrix (CM). Soft Odontostomatology Unit, IRCCS Cà Granda tissue healing was clinically evaluated on the basis of a specific healing index. Horizontal and Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Foundation, vertical ridge dimensional changes were assessed clinically and radiographically at baseline University of Milan, Via della Commenda 10, Milan 20122, Italy. and 6 months after implant placement.