Assessing Abuse of Dominance in the Platform Economy: a Case Study of App Stores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

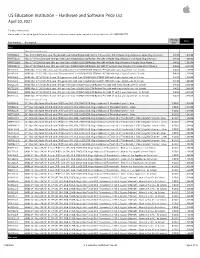

Apple US Education Price List

US Education Institution – Hardware and Software Price List April 30, 2021 For More Information: Please refer to the online Apple Store for Education Institutions: www.apple.com/education/pricelists or call 1-800-800-2775. Pricing Price Part Number Description Date iMac iMac with Intel processor MHK03LL/A iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel Iris Plus Graphics 640 w/Apple Magic Keyboard, Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,049.00 MXWT2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5300 w/Apple Magic Keyboard and Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,699.00 MXWU2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.3GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/512GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5300 w/Apple Magic Keyboard & Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,899.00 MXWV2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.8GHz 8-core 10th-gen Intel Core i7/8GB/512GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5500 XT w/Apple Magic Keyboard & Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 2,099.00 BR332LL/A BNDL iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-generation Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel IPG 640 with 3-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,168.00 BR342LL/A BNDL iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-generation Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel IPG 640 with 4-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,218.00 BR2P2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-generation Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/RP 5300 with 3-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,818.00 BR2S2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-generation Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/RP 5300 with 4-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,868.00 BR2Q2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.3GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/512GB -

Legal-Process Guidelines for Law Enforcement

Legal Process Guidelines Government & Law Enforcement within the United States These guidelines are provided for use by government and law enforcement agencies within the United States when seeking information from Apple Inc. (“Apple”) about customers of Apple’s devices, products and services. Apple will update these Guidelines as necessary. All other requests for information regarding Apple customers, including customer questions about information disclosure, should be directed to https://www.apple.com/privacy/contact/. These Guidelines do not apply to requests made by government and law enforcement agencies outside the United States to Apple’s relevant local entities. For government and law enforcement information requests, Apple complies with the laws pertaining to global entities that control our data and we provide details as legally required. For all requests from government and law enforcement agencies within the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act 1986, as amended), Apple will only provide content in response to a search issued upon a showing of probable cause, or customer consent. All requests from government and law enforcement agencies outside of the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined below in Emergency Requests), must comply with applicable laws, including the United States Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA). A request under a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty or the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (“CLOUD Act”) is in compliance with ECPA. Apple will provide customer content, as it exists in the customer’s account, only in response to such legally valid process. -

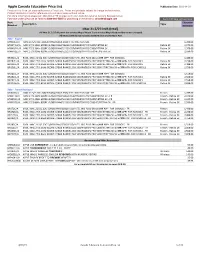

Eppplist-2021-04-20 EN.Xls

Apple Canada Education Price List Publication Date: 2021-04-20 Prices on this Price List supersede previous Price Lists. Prices and products subject to change without notice. Product descriptions are for reference only and can change without notice. For More Information please call 1800-800-2775 to speak with your Apple Educational Account Representative. Purchase Orders (PO) can be faxed to 1800-903-5285 for processing or e-mailed to: [email protected] Current Pricing, per unit cost Part Education Description Type Number Institution iMac 21.5/27-inch (Intel) All iMac 21.5/27 ship with the wireless Magic Mouse 2 and wireless Magic Keyboard (no numeric keypad). All iMacs listed do not include a CD/DVD drive and Firewire Port. iMac - English MHK03LL/A IMAC 21.5/2.3DC i5/8GB RAM/256GB SSD/INTEL IRIS PLUS 640 1,289.00 MXWT2LL/A IMAC 27/3.1GHz 6CORE i5/8GB RAM/256GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5300/RETINA 5K Retina 5K 2,079.00 MXWU2LL/A IMAC 27/3.3GHz 6CORE i5/8GB RAM/512GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5300/RETINA 5K Retina 5K 2,329.00 MXWV2LL/A IMAC 27/3.8GHz 8CORE i7/8GB RAM/512GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5500 XT/RETINA 5K Retina 5K 2,599.00 BR352LL/A BNDL IMAC 21.5/2.3DC i5/8GB RAM/256GB SSD/INTEL IRIS PLUS 640 w/3YR APP+ FOR SCHOOLS 1,448.00 BR2B2LL/A BNDL IMAC 27/3.1GHz 6CORE i5/8GB RAM/256GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5300/RETINA 5K w/3YR APP+ FOR SCHOOLS Retina 5K 2,238.00 BR2C2LL/A BNDL IMAC 27/3.3GHz 6CORE i5/8GB RAM/512GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5300/RETINA 5K w/3YR APP+ FOR SCHOOLS Retina 5K 2,488.00 BR2D2LL/A BNDL IMAC 27/3.8GHz 8CORE i7/8GB RAM/512GB SSD/RADEON PRO 5500 XT/RETINA 5K -

Set up Your Airtag Using Your Iphone, Ipad, Or Ipod Touch – Apple Support

Skip to content Manuals+ User Manuals Simplified. Home » Support » Set up your AirTag using your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch – Apple Support Set up your AirTag using your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch – Apple Support Contents [ hide 1 Set up your AirTag using your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch 1.1 What you need 1.2 Set up your AirTag 1.3 Change the name of your AirTag 1.4 If you can’t set up your AirTag 1.5 Learn more about using your AirTag with Find My 1.5.1 Related Manuals Set up your AirTag using your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch With AirTag, you can keep track of everyday items like your keys or a backpack. Learn how to set up your AirTag with your iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch. What you need An iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch with iOS 14.5 or iPadOS 14.5 or later and two-factor authentication turned on. Find My turned on. Bluetooth turned on. A strong Wi-Fi or cellular connection. Location Services turned on: Go to Settings > Privacy > Location Services. To be able to use Precision Finding and to see the most accurate location for your AirTag, turn on Location Access for Find My. Go to Settings > Privacy > Location Services, then scroll down and tap Find My. Check While Using the App or While Using the App or Widgets. Then turn on Precise Location. If you have a Managed Apple ID, you can’t set up an AirTag. Set up your AirTag 1. Make sure that your device is ready for setup. -

Legal Process Guidelines Government & Law Enforcement Outside the United States

Legal Process Guidelines Government & Law Enforcement outside the United States These guidelines are provided for use by government and law enforcement agencies outside of the United States when seeking information from Apple entities in the relevant region or country about customers of Apple’s devices, products and services. Apple will update these Guidelines as necessary. In these Guidelines, Apple shall mean the relevant entity responsible for customer information in a particular region or country. Apple, as a global company, has a number of legal entities in different jurisdictions which are responsible for the personal information which they collect and which is processed on their behalf by Apple Inc. For example, point of sale information in Apple’s retail entities outside the United States is controlled by Apple’s individual retail entities in each country. Apple Online Store and Apple Media Services related personal information may also be controlled by legal entities outside the United States as reflected in the terms of each service within a specific jurisdiction. Typically Apple’s legal entities outside the United States in Australia, Canada, Ireland and Japan are responsible for customer data related to Apple services within their respective regions. All other requests for information regarding Apple customers, including customer questions about information disclosure, should be directed to https://www.apple.com/privacy/contact/. These Guidelines do not apply to United States government and law enforcement requests made to Apple Inc. For government and law enforcement information requests, Apple complies with the laws pertaining to global entities that control our data and we provide details as legally required. -

Apple-Range Latest.Pdf

Computers and Technology 2021 September Computers Prices are subject to change without notice. MacBook Air 13.3-inch MacBook Pro 13.3-inch 8-core CPU | 7-core GPU | 16-core Neural Engine 2.0GHz quad-core 10th Gen i5 TurboBoost to 3.8GHz 8GB of unified memory 16GB 3733MHz LPDDR4X memory Retina dispay with True Tone Intel Iris Plus Graphics 2560-by-1600 resolution Retina display with True Tone 2x Thunderbolt/USB 4 ports 2560-by-1600 resolution Force Touch trackpad 4x Thunderbolt 3 USB-C ports Backlit Magic Keyboard + Touch ID Touch Bar and Touch ID WiFi 6 (802.11ax) + Bluetooth 5.0 Magic Keyboard Upto 18 hours battery Silent / fanless design NEW 256GB SSD storage $ 1,749.00 512GB SSD storage $ 3,099.00 MGN63X/A Space Grey MWP42X/A Space Grey SCHOOL MGN93X/A Silver MWP72X/A Silver EIT / TECH BACK TO FAVOURITES MGND3X/A Gold UNIVERSITY 512GB SSD storage $ 2,149.00 1TB SSD storage $ 3,449.00 MGN73X/A Space Grey MWP52X/A Space Grey Custom build options: MGNA3X/A Silver Custom build options: MWP82X/A Silver RAM: 16GB SSD: 512GB, 1TB, 2TB MGNE3X/A Gold RAM: 16GB or 32GB CPU: 2.0GHz 4-core 10th Gen i5 Turbo to 3.8GHz SSD: 1TB or 2TB or 4TB CPU:: 2.3GHz 4-core 10th Gen i7 Turbo to 4.1GHz MacBook Pro 13.3-inch MacBook Pro 16-inch 8-core CPU | 8-core GPU | 16-core Neural Engine 8GB of unified memory 16-inch 6-Core i7 (Intel) Retina dispay with True Tone 2.6GHz 6-core 9th Gen i7 TurboBoost to 4.5GHz 2560-by-1600 resolution 16GB 2666MHz DDR4 memory 2x Thunderbolt/USB 4 ports 512GB PCIe based flash storage Force Touch trackpad Radeon Pro 5300M - 4GB -

Printout 2106.Pages

June 2021 Vol. XL, No 6 printoutKeystone MacCentral Macintosh Users Group www.keystonemac.com Keystone MacCentral June Program June 15, 2021 06:30 PM Join our Zoom Meeting The link is provided on our email. We have virtual meetings via Zoom on the third Tuesday of each month. Emails will be sent out prior to each meeting. Just follow the directions/invitations each month on our email — that is, just click on the link. Page 1 Contents June Meeting .......................................................................................................... 1 Board of Directors Apple’s AirTag Promises to Help You Find Your Keys President By Julio Ojeda-Zapata ............................................................................ 3 - 5 Linda J Cober Apple Releases iOS 14.5, iPadOS 14.5, macOS 11.3, watchOS 7.4, and tvOS 14.5 By Adam Engst & Josh Centers ............................... 5 - 10 Recorder Standard Ebooks Makes Classic Texts Beautiful By Joh Centers ... 11 - 13 Wendy Adams Prevent Apple’s Updated Podcasts App from Eating Your Storage By Josh Centers .......................................................... 13 - 16 Treasurer Tim Sullivan Program Director Keystone MacCentral is a not-for-profit group of Macintosh enthusiasts who Dennis McMahon generally meet the third Tuesday of every month to exchange information, participate in question-and-answer sessions, view product demonstrations, and Membership Chair obtain resource materials that will help them get the most out of their computer systems. Meetings are free and open to the public. The Keystone MacCentral printout is Eric Adams the official newsletter of Keystone MacCentral and an independent publication not affiliated or otherwise associated with or sponsored or sanctioned by any for-profit Correspondence Secretary organization, including Apple Inc. Copyright © 2021, Keystone MacCentral, 310 Somerset Drive, Shiresmanstown, PA 17011. -

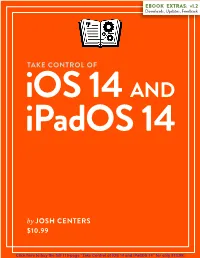

Take Control of Ios 14 and Ipados 14 (1.2) SAMPLE

EBOOK EXTRAS: v1.2 Downloads, Updates, Feedback TAKE CONTROL OF iOS 14 AND iPadOS 14 by JOSH CENTERS $10.99 Click here to buy the full 115-page “Take Control of iOS 14 and iPadOS 14” for only $10.99! Table of Contents Read Me First ............................................................... 6 Updates and More ............................................................. 6 Basics .............................................................................. 7 Touch and Hold ................................................................. 7 What’s New in Version 1.2 .................................................. 7 What Was New in Version 1.1 ............................................. 7 Introduction ................................................................ 9 iOS 14 and iPadOS 14 Quick Start .............................. 10 An iOS Crash Course .................................................. 12 Navigate the Lock Screen ................................................. 12 Access Control Center ...................................................... 14 Manage Apps on the Home Screen ..................................... 15 Switch Apps and Multitask ................................................ 17 Share from Apps ............................................................. 19 Use Siri .......................................................................... 21 Search ........................................................................... 21 Features Added Since 14.0 ........................................ 23 AirTag -

Airtags Reading Comprehension

AirTags eslflow.com Read the article and answer the questions. How much time do you waste looking for things around your house? Maybe help is here. The AirTag is a device that you can use with your iPhone. It lets you find things in your house, like your keys or your wallet. It’s so accurate that it can tell you exactly where your keys are, even if they are far away. It can tell you where to go to find them. I decided to give it a test. I used it to find my car key, a wallet and my car. It uses Bluetooth to communicate with your iPhone or iPad. The AirTag works with iPhones that are new or old. To find an item, you open the Find My app, select an item and tap Find. From there, the app will form a connection with the AirTag. The app combines data gathered with the phone’s camera, sensors and ultrawideband chip to direct you to the tag. First, I asked my son to hide an AirTag attached to my car key somewhere in our house. Apple's Find My app showed me an arrow pointing to a bed, and I touched a button to make the AirTag play a sound. After looking under the bed, I found the AirTag and key. It took about 90 seconds. The most difficult experiment was an AirTag hidden inside a wallet. My app pointed toward a wardrobe, but it couldn’t tell me which jacket the tag was inside. After removing four jackets from the wardrobe, I finally found the correct jacket with the AirTag. -

NCT Personal Tracker Safety Guide 1.0 Endtab.Org

VERSION 1.0 E NDTAB.ORG NONCONSENSUAL TRACKING & PERSONAL TRACKERS a victim resource guide GUIDE OVERVIEW Nonconsensual tracking (NCT) is defined as "the monitoring of a I person's location without their consent." The proliferation of 1.26 IN. personal tracking devices (AirTags, I I Tiles, etc.) has created new NCT risks for victims of gender-based violence, stalking and trafficking. This guide provides information APPLE AIRTAG and tools to address and prevent NCT situations where personal tracking devices are involved. PERSONAL TRACKERS The Problem: Companies like Apple and Tile are flooding the market with small, inexpensive and highly effective tracking devices that can be secretly placed in a victim's bag, clothing or vehicle to nonconsensually track them anywhere they go. It is now critical that communities, schools and organizations working with victim populations understand this threat and how to address it. Version 1.0 Details: Cost: $29. Battery life: 1 year. APPLE How they track: A billion+ Apple devices form a tracking network to locate AirTags AIRTAGS anywhere in the world. Nearby AirTags are 1 located using bluetooth. Learn more here. NCT Alerts: Apple device owners should receive a security alert within 24-hours of an unknown AirTag tracking them (unless it is also near the AirTag owner's device). Android users will not receive an alert. Regardless, the AirTag itself should also emit a sound alert. Learn more here. AM I BEING TRACKED?? UNLIKELY IF: POSSIBLE IF: LIKELY IF: 1) You do not cohabitate 1) You do cohabitate with or 1) You received an with or see the suspected see the suspected party AirTag alert or party every 24 hrs and every 24 hrs and 2) You haven't received an 2) You haven't received an 2) Heard an AirTag AirTag alert (iPhone only) or AirTag alert (iPhone only) or beeping. -

Apple US Education Price List

US Education Institution – Hardware and Software Price List August 12, 2021 For More Information: Please refer to the online Apple Store for Education Institutions: www.apple.com/education/pricelists or call 1-800-800-2775. Pricing Price Part Number Description Date iMac iMac with Intel processor MHK03LL/A iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel Iris Plus Graphics 640 w/Apple Magic Keyboard, Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,049.00 MXWT2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5300 w/Apple Magic Keyboard and Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,699.00 MXWU2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.3GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/512GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5300 w/Apple Magic Keyboard & Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 1,899.00 MXWV2LL/A iMac 27" 5K/3.8GHz 8-core 10th-gen Intel Core i7/8GB/512GB SSD/Radeon Pro 5500 XT w/Apple Magic Keyboard & Apple Magic Mouse 2 8/4/20 2,099.00 BR332LL/A BNDL iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-generation Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel IPG 640 with 3-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,168.00 BR342LL/A BNDL iMac 21.5"/2.3GHz dual-core 7th-generation Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/Intel IPG 640 with 4-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,218.00 BR2P2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-generation Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/RP 5300 with 3-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,818.00 BR2S2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.1GHz 6-core 10th-generation Intel Core i5/8GB/256GB SSD/RP 5300 with 4-year AppleCare+ for Schools 8/4/20 1,868.00 BR2Q2LL/A BNDL iMac 27" 5K/3.3GHz 6-core 10th-gen Intel Core i5/8GB/512GB -

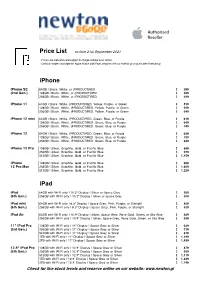

Full Apple Price List (Pdf)

Price List as from 21st September 2021 - Prices are indicative and subject to change without prior notice - Cellular models available for Apple Watch and iPads, enquire with our staff for pricing at [email protected] iPhone iPhone SE 64GB | Black, White, or (PRODUCT)RED £ 359 (2nd Gen.) 128GB | Black, White, or (PRODUCT)RED £ 399 256GB | Black, White, or (PRODUCT)RED £ 499 iPhone 11 64GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Yellow, Purple, or Green £ 519 128GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Yellow, Purple, or Green £ 559 256GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Yellow, Purple, or Green £ 649 iPhone 12 mini 64GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 619 128GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 649 256GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 749 iPhone 12 64GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 699 128GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 729 256GB | Black, White, (PRODUCT)RED, Green, Blue, or Purple £ 829 iPhone 12 Pro 128GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 889 256GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 979 512GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 1,159 iPhone 128GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 959 12 Pro Max 256GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 1,059 512GB | Silver, Graphite, Gold, or Pacific Blue £ 1,229 iPad iPad 64GB with Wi-Fi only | 10.2" Display | Silver or Space Grey £ 269 (9th Gen.) 256GB with Wi-Fi only | 10.2" Display | Silver or Space Grey £ 389 iPad mini 64GB with Wi-Fi only | 8.3" Display |