Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prunus Maackii

Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Species: Prunus maackii Amur Chokecherry, Manchurian Chokecherry Cultivar Information * See specific cultivar notes on next page. Ornamental Characteristics Size: Tree > 30 feet Height: 35 to 45' tall, 25 to 35' wide Leaves: Deciduous Shape: Young trees are pyramidal, rounded and dense at maturity Ornamental Other: full sun Environmental Characteristics Light: Full sun Hardy To Zone: 3a Soil Ph: Can tolerate acid to alkaline soil (pH 5.0 to 8.0) Environmental Other: full sun Insect Disease aphids, scale, borers Bare Root Transplanting Any Other Native to Manchuria and Korea Moisture Tolerance 1 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Occasionally saturated Consistently moist, Occasional periods of Prolonged periods of or very wet soil well-drained soil dry soil dry soil 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 2 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Cultivars for Prunus maackii Showing 1-3 of 3 items. Cultivar Name Notes Amber Beauty 'Amber Beauty'- Forms a uniform tree with slightly ascending branches Goldspur 'Goldspur' (a.k.a.'Jefspur') - dwarf, multi-stemmed, narrowly upright and columnar growth habit; resistant to black knot; grows to 15' tall x 10' wide; Goldrush 'Goldrush' (a.k.a. 'Jefree') - upright growth habit; resistant to black rot; improved resistance to frost cracking; grows to 25' tall x 16' wide 3 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Photos Prunus maackii - Bark Prunus maackii - Bark 4 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Bark Prunus maackii - Leaves 5 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit Prunus maackii - Leaves 6 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit Prunus maackii - Habit 7 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus maackii - Habit 8. -

Four Master Teachers Who Fostered American Turn-Of-The-(20<Sup>TH

MYCOTAXON ISSN (print) 0093-4666 (online) 2154-8889 Mycotaxon, Ltd. ©2021 January–March 2021—Volume 136, pp. 1–58 https://doi.org/10.5248/136.1 Four master teachers who fostered American turn-of-the-(20TH)-century mycology and plant pathology Ronald H. Petersen Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37919-1100 Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract—The Morrill Act of 1862 afforded the US states the opportunity to found state colleges with agriculture as part of their mission—the so-called “land-grant colleges.” The Hatch Act of 1887 gave the same opportunity for agricultural experiment stations as functions of the land-grant colleges, and the “third Morrill Act” (the Smith-Lever Act) of 1914 added an extension dimension to the experiment stations. Overall, the end of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th was a time for growing appreciation for, and growth of institutional education in the natural sciences, especially botany and its specialties, mycology, and phytopathology. This paper outlines a particular genealogy of mycologists and plant pathologists representative of this era. Professor Albert Nelson Prentiss, first of Michigan State then of Cornell, Professor William Russel Dudley of Cornell and Stanford, Professor Mason Blanchard Thomas of Wabash College, and Professor Herbert Hice Whetzel of Cornell Plant Pathology were major players in the scenario. The supporting cast, the students selected, trained, and guided by these men, was legion, a few of whom are briefly traced here. Key words—“New Botany,” European influence, agrarian roots Chapter 1. Introduction When Dr. Lexemual R. -

Nursery Price List

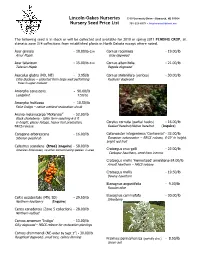

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Phylogenetic Inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) Using Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear Ribosomal ITS Sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T

Journal of Systematics and Evolution 46 (3): 322–332 (2008) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1002.2008.08050 (formerly Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica) http://www.plantsystematics.com Phylogenetic inferences in Prunus (Rosaceae) using chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences 1Jun WEN* 2Scott T. BERGGREN 3Chung-Hee LEE 4Stefanie ICKERT-BOND 5Ting-Shuang YI 6Ki-Oug YOO 7Lei XIE 8Joey SHAW 9Dan POTTER 1(Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, MRC 166, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA) 2(Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA) 3(Korean National Arboretum, 51-7 Jikdongni Soheur-eup Pocheon-si Gyeonggi-do, 487-821, Korea) 4(UA Museum of the North and Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-6960, USA) 5(Key Laboratory of Plant Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650204, China) 6(Division of Life Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 200-701, Korea) 7(State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) 8(Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, TN 37403-2598, USA) 9(Department of Plant Sciences, MS 2, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA) Abstract Sequences of the chloroplast ndhF gene and the nuclear ribosomal ITS regions are employed to recon- struct the phylogeny of Prunus (Rosaceae), and evaluate the classification schemes of this genus. The two data sets are congruent in that the genera Prunus s.l. and Maddenia form a monophyletic group, with Maddenia nested within Prunus. -

North Dakota Tree Selector Amur Chokecherry

NORTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY North Dakota Tree Selector Amur Chokecherry General Scientific Name: Prunus Description maackii Prunus maackii, commonly called Manchurian cherry, Amur cherry Family: Roseaceae (Rose) or Amur chokecherry, is a graceful ornamental flowering cherry tree Hardiness: Zone 3 that typically grows 20-30’ tall with a dense, broad-rounded crown. It is native to Manchuria, Siberia and Korea. It is perhaps most Leaves: Deciduous noted for its attractive, exfoliating golden brown to russet Plant type: Tree bark. Fragrant flowers appear in late spring and are followed by black fruits. Growth Preferences Rate: N/A Light: Full sun Mature height: 25-45’ Water: Medium Longevity: Short Soil: Average well drained soils Power Line: No Comments Ornamental An excellent tree for lawns or as a street tree. It can be used Flowers: White to cream individually or in a grouping of multiple species. Amur chokecherry fruits are excellent for wildlife and birds while the tree serves as a Fruit: Black cherry-like nesting site for songbirds. It is a short lived tree with an expected Fall Color: Yellow lifespan of 25-30 years. Credits: Tree Selector Website, https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/trees/handbook/th-3-13.pdf www.ag.ndsu.edu/tree-selector NDSU does not discriminate in its programs and activities on the basis of age, color, gender expression/identity, genetic inf ormation, marital status, national origin, participation in lawful off-campus activity, physical or mental disability, pregnancy, public assistance status, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, spousal relationship to curr ent employee, or vete ran status, as applicable. -

George P. Clinton

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MKMOIRS VOLUME XX SIXTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF GEORGE PERKINS CLINTON 1867-1937 BY CHARLES THOM AND E. M. EAST PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1938 GEORGE PERKINS CLINTON CHRONOLOGY 1867. Born May 7, at Polo, Illinois. 1886. Graduated, Polo High School. 1890. B.S., University of Illinois. Assistant Botanist, Agricultural Experiment Station, and Assistant in Botany in the Uni- versity of Illinois. 1894. M.S. in Botany. 1900. Graduate Student in Botany, Harvard. 1901. M.S., Harvard. 1902. D.Sc, Harvard. 1902. Botanist. Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station at New Haven, July 1, 1902. 1902-1925. Botanist, State Board of Agriculture (Connecticut). 1903-1927. Chairman, Committee on Fungous Diseases of Connecticut Pomological Society. 1904. Agent and Expert, Office of Experiment Stations, U. S. Department of Agriculture, studying coffee diseases in Puerto Rico. 1906-1907. Studied fungous diseases of the brown-tail moth at Harvard, Iyo6. Continued the study in Japan, 1907. 1908. Agent, Bureau of Entomology, U. S. Department of Agri- culture, to prevent the spread of moths. 1909. Collaborator, to seek parasites of the Gypsy moth in Japan. 1915-1927. Lecturer in Forest Pathology, Yale. 1916. Collaborator, Plant Disease Survey, U. S. Department of Agriculture. 1926-1929. Research Associate in Botany, Yale. 1937. Died, August 13th at New Haven, Connecticut. GEORGE PERKINS CLINTON* 1867-1937 BY CHARLES THOM AND E. M. EAST George Perkins Clinton was horn in Polo, Illinois, May 7, 1867. He was known to his fellows as Botanist of the Con- necticut Agricultural Experiment Station, a post which he held for thirty-five years. -

Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830S-1860S)

Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Hung, Kuang-Chi. 2013. Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray's Citation Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:20:57 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11181178 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) A dissertation presented by Kuang-Chi Hung to The Department of the History of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts July 2013 © 2013–Kuang-Chi Hung All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Janet E. Browne Kuang-Chi Hung Finding Patterns in Nature: Asa Gray’s Plant Geography and Collecting Networks (1830s-1860s) Abstract It is well known that American botanist Asa Gray’s 1859 paper on the floristic similarities between Japan and the United States was among the earliest applications of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory in plant geography. Commonly known as Gray’s “disjunction thesis,” Gray's diagnosis of that previously inexplicable pattern not only provoked his famous debate with Louis Agassiz but also secured his role as the foremost advocate of Darwin and Darwinism in the United States. -

Seed Stratification Treatments for Two Hardy Cherry Species

Tree Planter's Notes, Vol. 37, No. 3 (1986) Summer 1986/35 Seed Stratification Treatments for Two Hardy Cherry Species Greg Morgenson Assistant nurseryman, Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries, Bismark, ND The seed-propagated selection Information regarding seed Seed of Mongolian cherry (Prunus 'Scarlet' Mongolian cherry (figs. 1 propagation of these two species is fruticosa Pallas) germinated best after and 2) has recently been released limited. Initial late fall nursery seedings 30 days of warm plus 90 days of cold by the USDA Soil Conservation resulted in minimal germination the stratification. Amur chokecherry Service for conservation purposes in following spring but in satisfactory (Prunus maackii Rupr.) was best after the Northern Plains (4). germination the second spring after 30 days of warm plus 60 days of cold Prunus maackii is placed in the planting. stratification. Longer stratification subgenus Padus. It ranges from Seed of Prunus species require a periods resulted in germination during Manchuria to Korea and is rated as period of after-ripening to aid in storage. Tree Planters' Notes zone II in hardiness (3). It is a overcoming embryo dormancy (2). 37(3):3538; 1986. nonsuckering tree that grows to 15 Several species require a warm meters in height. Its leaves are dull stratification period followed by cold green. The dark purple fruits are borne stratification. It was believed that P. in racemes and are utilized by wildlife. fruticosa and P. maackii might benefit The genus Prunus contains many Amur chokecherry is often planted as from this. Researchers at the Morden native and introduced species that are an ornamental because of its Manitoba Experimental Farm found that hardy in the Northern Plains and are copper-colored, flaking bark, but it germination of P. -

An Albertan Plant Journal

An Albertan Plant Journal By Traci Berg Disclaimer *My plant journal lists over 70 species that are commonly used in landscaping and gardening in Calgary, Alberta, which is listed by Natural Resources Canada as a 4a zone as of 2010. These plants were documented over several plant walks at the University of Calgary and at Eagle Lake Nurseries in September and October of 2018. My plant journal is by no means exclusive; there are plenty of native and non-native species that are thriving in Southern Alberta, and are not listed here. This journal is simply meant to serve as both a personal study tool and reference guide for selecting plants for landscaping. * All sketches and imagery in this plant journal are © Tessellate: Craft and Cultivations by Traci Berg and may not be used without the artist’s permission. Thank you, enjoy! Table of Contents Adoxaceae Family 1 Viburnum lantana “Wayfaring Tree” 1 Viburnum trilobum “High Bush Cranberry” 1 Anacardiaceae Family 2 Rhus typhina x ‘Bailtiger’ “Tiger Eyes Sumac” 2 Asparagaceae Family 3 Polygonatum odoratum “Solomon’s Seal” 3 Hosta x ‘June’ “June Hosta” 3 Betulaceae Family 4 Betula papyrifera ‘Clump’ “Clumping White/Paper Birch” 4 Betula pendula “Weeping Birch” 4 Berberidaceae Family 5 Berberis thunbergii “Japanese Barberry” 5 Caprifoliaceae Family 5 Symphoricarpos albus “Snowberry” 5 Cornaceae Family 6 Cornus alba “Ivory Halo/Silver Leaf Dogwood” 6 Cornus stolonifera/sericea “Red Osier Dogwood” 6 Cupressaceae Family 7 Juniperus communis “Common Juniper” 7 Juniperus horizontalis “Creeping/Horizontal Juniper” 7 Juniperus sabina “Savin Juniper” 8 Thuja occidentalis “White Cedar” 8 Elaegnaceae Family 9 Shepherdia canadensis “Russet Buffaloberry” 9 Elaeagnus commutata “Wolf Willow/Silverberry” 9 Fabaceae Family 10 Caragana arborscens “Weeping Caragana” 10 Caragana pygmea “Pygmy Caragana” 10 Fagaceae Family 11 Quercus macrocarpa “Bur Oak” 11 Grossulariaceae Family 12 Ribes alpinum “Alpine Currant” 12 Hydrangeaceae Family 12 Hydrangea paniculata ‘Grandiflora’ “Pee Gee Hydrangea” 13 Philadelphus sp. -

Interspecific Hybridizations in Ornamental Flowering Cherries

J. AMER.SOC.HORT.SCI. 138(3):198–204. 2013. Interspecific Hybridizations in Ornamental Flowering Cherries Validated by Simple Sequence Repeat Analysis Margaret Pooler1 and Hongmei Ma USDA-ARS, U.S. National Arboretum, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Building 010A, Beltsville, MD 20705 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. simple sequence repeat, molecular markers, plant breeding, Prunus ABSTRACT. Flowering cherries belong to the genus Prunus, consisting primarily of species native to Asia. Despite the popularity of ornamental cherry trees in the landscape, most ornamental Prunus planted in the United States are derived from a limited genetic base of Japanese flowering cherry taxa. Controlled crosses among flowering cherry species carried out over the past 30 years at the U.S. National Arboretum have resulted in the creation of interspecific hybrids among many of these diverse taxa. We used simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers to verify 73 of 84 putative hybrids created from 43 crosses representing 20 parental taxa. All verified hybrids were within the same section (Cerasus or Laurocerasus in the subgenus Cerasus) with no verified hybrids between sections. Ornamental flowering cherry trees are popular plants for pollen parent bloomed before the seed parent, anthers were street, commercial, and residential landscapes. Grown primar- collected from the pollen donor just before flower opening and ily for their spring bloom, flowering cherries have been in the allowed to dehisce in gelatin capsules which were stored in United States since the mid-1850s (Faust and Suranyi, 1997), paper coin envelopes in the refrigerator before use. In most and they gained in popularity after the historic Tidal Basin cases, the seed parent was emasculated before pollination. -

William Trelease

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES W I L L I A M T RELEASE 1857—1945 A Biographical Memoir by L O U I S O T T O KUNKEL Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1961 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. WILLIAM TRELEASE February 22, i8$j-]anuary 1, BY LOUIS OTTO KUNKEL ILLIAM TRELEASE is known as a plant taxonomist but his early Winterest in natural history indicated a preference for other fields. His first papers dealt largely with pollination of plants by in- sects and birds. Other early publications were on bacteria, parasitic fungi, and plant diseases. Some were entirely entomological. His thesis for the Doctor of Science degree at Harvard University was on "Zoogloeae and Related Forms." It probably was the first in this country in the field of bacteriology. But his later and perhaps deeper interests were in taxonomy. It is said that each epoch brings forth leaders to meet the demands of the time. A hundred years ago and for several decades thereafter the vast central and western portions of North America were being settled by pioneers who established homes in the forests and on the prairies. They also built cities but these remained relatively small for many years. Most of the scanty population lived on farms. It is not easy to picture or to comprehend fully the conditions and needs of those years. Americans of that time lived close to nature and were of necessity familiar with their local floras. -

Screening Ornamental Cherry (Prunus) Taxa for Resistance to Infection by Blumeriella Jaapii

HORTSCIENCE 53(2):200–203. 2018. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI12563-17 and likely most effective method for long- term disease management. Disease-resistant taxa have been found for use in sour and Screening Ornamental Cherry sweet cherry breeding programs (Stegmeir et al., 2014; Wharton et al., 2003), and (Prunus) Taxa for Resistance to detached leaf assays have been developed (Wharton et al., 2003). A field screening of Infection by Blumeriella jaapii six popular ornamental cultivars revealed differential resistance in those taxa as well Yonghong Guo (Joshua et al., 2017). The objectives of the Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit, U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. present study were 2-fold: 1) to screen Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 10300 Baltimore a large and diverse base of ornamental flowering cherry germplasm to identify the Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 most resistant taxa for use in landscape Matthew Kramer plantings and in our breeding program, and 2) to verify that our detached leaf assay Statistics Group, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research for this fungus was effective for flowering Service, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 cherry taxa, where whole tree assays are Margaret Pooler1 often impractical. Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit, U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Materials and Methods Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, MD 20705 Plant materials. Sixty-nine diverse acces- sions of ornamental flowering cherries were Additional index words. breeding, flowering cherry, germplasm evaluation, cherry leaf spot selected for testing. These plants were mature Abstract. Ornamental flowering cherry trees are important landscape plants in the trees representing multiple accessions of United States but are susceptible to several serious pests and disease problems.