Legal Issues: Internships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice for Employers, Creating a Successful Internship

Pinkney Hall 410-626-2501 [email protected] AAddvviiccee ffoorr EEmmppllooyyeerrss:: ' CCrreeaattiinngg aa SSuucccceessssffuull IInntteerrnnsshhiipp ' From the intern’s perspective: The key to a successful internship is to have the opportunity to participate in meaningful work assignments that allow the intern to learn more about a career through practice by working closely with a mentor who takes an active interest in providing guidance and supervision. An intern has the specific goal of gaining knowledge, skills, and/or further understanding of a particular industry. From the employer’s perspective: The benefits for the employer are the opportunities to pre-screen and recruit highly qualified and motivated students to meet the company’s needs and provide the organization with fresh ideas and insights. Ideally, an internship strikes a balance between the activities that provide a meaningful learning experience for the intern and the activities that will increase productivity in the organization. Creating a Successful Internship Clearly-Defined, Meaningful Work Assignments • Interns want to be productive and learn new skills. It’s important to clearly define the types of assignments and supervision an intern will have during the internship. This will clarify the expectations of both the intern and the supervisor. • Short-term and long-term assignments help build valuable skills. Long-term assignments will ensure that the intern always has something to do to stay productive (especially during times when a mentor is unavailable). • Interns don’t usually expect to be constantly working on high priority assignments and tasks, but it is nice to provide them with some ownership of a meaningful project. -

Internship Toolkit for Employers

INTERNSHIP TOOLKIT FOR EMPLOYERS NMU CAREER SERVICES Office: 3302.3 C.B. Hedgcock | Mailing: 1401 Presque Isle Ave. Marquette, MI 49855 t: (906) 227-2800 | f: (906) 227-2807 [email protected] | www.nmu.edu/careerservices www.facebook.com/CareerServicesNMU | Twitter: NMUCareerServic Pinterest: www.pinterest.com/NMUCareerServices | Instagram: NMUCareerServices Handshake: https://app.joinhandshake.com Contents Why Choose NMU Interns? .......................................................................................................................... 3 What are Internships? ................................................................................................................................. 4 Internship Overview ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Benefits to Employers ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Internship Experience Criteria............................................................................................................................. 4 NMU Work Experience Types ............................................................................................................................. 4 Liability & Legal Concerns ............................................................................................................................ 5 Paid vs. Unpaid (A Quick Overview Of FLSA) ...................................................................................................... -

Parental Leave Guide Contents

Parental Leave Guide Contents Introduction 3 Statutory Leave in Great Britain 4 Statutory Leave: Key problem areas 5 Enhancing the statute 6 Areas to consider 6 Best Practices: Enhancing the statute 6 Building your Leave Programme 8 Before Leave 8 1.1 Areas to consider 8 1.2 Best Practices: Before Leave 8 During Leave 9 2.1 Areas to consider 9 2.2 Best Practices: During Leave 9 After Leave 10 3.1 Areas to consider 10 3.2 Best Practices: Fostering an inclusive culture after Leave 10 Building a more inclusive future 11 Pitching a new policy 12 Parental Leave Costing Tool 13 Further Resources 13 Portfolio Company Support 13 Authors 14 Contributors 14 Next Steps 14 Introduction The business case for diversity and inclusion is strong and growing Supported by over 25 UK venture capital and technology firms, this stronger: it helps drive innovation, challenge entrenched ways of thinking guide is designed to support VC partners in not only amending or and improve financial performance.1 Yet where diversity builds a workforce introducing their Parental Leave policies but in also guiding policy fit for growth, inclusion drives their retention. Cultures that champion and redevelopment across portfolio companies. The guide offers actionable not condemn the authenticity and individuality of their employees are recommendations, specific considerations for the venture capital industry, more likely to secure the talent needed: a study conducted by McKinsey and advice to help expectant parents pitch an enhanced policy to their in 2020 indicated that from a pool of job-seekers, 39% decided not to employer. -

Paid Internship Program Guidelines Final

STATE OF CALIFORNIA--HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES AGENCY EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENTAL SERVICES 1600 NINTH STREET, Room 320, MS 3-9 SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 TTY (916) 654-2054 (For the Hearing Impaired) (916) 654-1958 July 28, 2016 TO: REGIONAL CENTER EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS SUBJECT: GUIDELINES FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF PAID INTERNSHIP PROGRAM A. PURPOSE Welfare and Institutions Code (WIC) was amended to add section 4870 (enclosed) to encourage competitive integrated employment (CIE) for individuals with developmental disabilities (consumers). CIE is full- or part-time work for which an individual is paid minimum wage or greater in a setting with others who do not have disabilities. Section 4870 authorizes funding to the Department of Developmental Services (Department) for a paid internship program. The purpose of the program is to increase the vocational skills and abilities of consumers who choose, via the Individual Program Plan (IPP) process, to participate in an internship. Goals of this program include the acquisition of experience and skills for future paid employment, or for the internship itself to lead to full- or part-time paid employment in the same job. This correspondence provides guidance for the implementation of the paid internship program. The guidelines were developed as a collaborative effort, with input from various stakeholders, as a result of two statewide meetings and other means. B. IMPLEMENTATION Internships are predicated on the person-centered planning process. Regional centers are responsible for informing consumers and the community about the paid internship program. Guidelines for the paid internship program are as follows: 1. Regional centers should work with service providers to provide outreach to consumers, families, schools, potential employers and any other entities to facilitate the success of the internship program. -

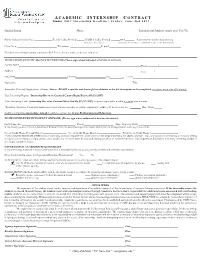

Internship Contract

A C A D E M I C I N T E R N S H I P CO N T R A C T Summer 2 0 1 7 I n t e r n s h i p D e a d l i n e : F r i d a y , June 2nd 2017 Student Intern Major International Student? (circle one) Yes/No Banner Identification No. ________ Total Credits Earned _____ UMW Credits Earned GPA______ Total Semester Credits w/internship______ (Must have 12 or above) (Must have 2.0 or above) (19cr+ will require overload permission) Class Year Telephone E-mail Previous internships completed for credit? Please list site name, semester and year ______________________________________________________________ TO BE COMPLETED BY AGENCY SUPERVISOR (Please sign where indicated at bottom of contract) Agency Name Phone ( ) Address Fax ( ) City/State________________________________________Country_______________________Zip _ E-mail Supervisor Title Internship Title and Description of Duties: (Intern: Attach a specific and thorough list of duties or the job description to be completed; can be no more than 30% clerical) Date Internship Begins: (Internship Hrs to be Counted Cannot Begin Before (05/13/2017) ____________ Date Internship Ends: (Internship Hrs to be Counted Must End By (07/27/2017) or special approval is needed to extend past this date___________ Total Hrs./Semester (must meet minimum requirements for number of credits requested (1 credit = 42 hours at site etc. ) ________ Hrs./Week ______ Students completing internships abroad should also contact the Center For International Education. TO BE COMPLETED BY FACULTY SPONSOR (Please sign where indicated at bottom of contract) Faculty Sponsor Phone Major Granting Credit If the faculty sponsor is from a department different from the department granting credit, chairs from both departments must sign the contract. -

Student Internship Agreement I, the Undersigned Student, Agree To

Student Internship Agreement I, the undersigned student, agree to accept an internship with the agency named below. If I am placed in a paid position, I agree to accept the rate of pay stipulated below. I enter into this internship agreement with the full knowledge that the internship agency has committed considerable time and resources so that I can develop vocational competence through the internship experience. I further agree to comply with the following conditions of the internship: CONDITIONS OF INTERNSHIP Time Off The student intern must be on the job regularly and punctually. He/she has only the privileges allowed other regular employees of the agency. He/she must not ask the employer for or take time off from work for any university requirements without first obtaining the consent of his/her Agency Internship Supervisor. Students will not be allowed to take academic work for credit that conflicts with regularly scheduled work hours. Absence from Work The tasks performed by students in their internships are part of a carefully planned and scheduled program of work. A student’s absence from work necessitates rescheduling and planning of performance expected of him/her. Therefore, in case of sickness or other emergency necessitating a student’s absence from work, the employer should be notified by telephone as early as possible. If an absence will cause the student to miss a full week or more, then his/her University Internship Supervisor should also be notified. Layoff Any student intern who is permanently or temporarily laid off must immediately notify the University Internship Supervisor. -

About Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton

* Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton thanks Laurence A. Shapero of Riddell Williams P.S. for contributing content related to 401(k) plans and other benefits. About Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton LLP Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton LLP is a law firm based in San Diego, California that specializes in the representation of private and public sector employers in discrimination, harassment, wrongful termination, wage & hour, trade secret, and other employment-related claims before state and federal courts and administrative agencies. In addition to litigation, the firm’s attorneys counsel employers on compliance matters, employment transactions, investigations and other day-to-day labor and employment law matters covering all fifty states. Paul, Plevin also has a portfolio of innovative training programs to assist employers with employee training in harassment prevention, investigations, effective management within the law, and other employment-related issues. The firm’s commitment to excellence has been recognized by its clients and peers. California Law Business named Paul, Plevin as one of California's top five defense-side labor and employment boutiques. For several years the firm has been named by Fortune 500 companies as a "Go To" firm for labor and employment law services in Fortune's annual survey of leading corporate legal departments. For more information about Paul, Plevin please contact Managing Partner Fred M. Plevin. Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton LLP 401 B Street . 10th Floor . San Diego, CA 92101 . (619) 237-5200 . www.paulplevin.com The information provided in this document is not legal advice. 2 © 2010 Paul, Plevin, Sullivan & Connaughton LLP TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction...........................................................................................................4 II. -

Statutory Minimum Wage: Notes for Student Employees and Employers

Statutory Minimum Wage does not apply to the following specified student employees under the Minimum Wage Ordinance (Cap. 608): student interns; and work experience students during a period of exempt student employment. Note: ● Unless otherwise specified, the Minimum Wage Ordinance applies to every employee, his employer and the contract of employment under which he is engaged. However, the Minimum Wage Ordinance does not apply to interns/students with no employment relationship with the host organisation or company. ● The exemption from Statutory Minimum Wage does not apply if a work experience student has not agreed with the employer to treat a certain period as a period of exempt student employment. This booklet explains in simple terms the details of exemption for specified student interns and work experience students during a period of exempt student employment under the Minimum Wage Ordinance. The interpretation of the Minimum Wage Ordinance should be based on its original text. The full text of the Ordinance has been uploaded to the Hong Kong e-Legislation of the Department of Justice website (www.elegislation.gov.hk). For details of Statutory Minimum Wage, please refer to the Statutory Minimum Wage: Reference Guidelines for Employers and Employees published by the Labour Department. 1 Kinds of programme enrolled Students Interns & Student Interns Work Experience Students Work Experience Students have to fulfil the following exemption criteria Schedule 1 to the Minimum Wage Ordinance; or for Statutory Minimum Wage. student employees -

Student Evaluation of Internship Experience 1

STUDENT EVALUATION OF INTERNSHIP EXPERIENCE The questions below are intended to help us determine if you gained practical experience, knowledge, and/or skills from your recent internship experience and if you would recommend this internship experience to other students. Name: Semester of Internship: Fall Spring Summer Year: ___________ Organization where you interned: __________________________________________________________ Department: ________________________________________________________________________ City: State: Supervisor: What resources did you use to find your internship? (Check all that apply) Career Services Office/Internship Coordinator Faculty General Internet Sites Family/Friend Previous Employer Other: ________________________________________________________________ Please rate the following questions about your internship using the following scale: 5 = Strongly 4 = Agree 3 = Neutral 2 = Disagree 1 = Strongly NA=Not Agree Disagree applicable • This experience gave me a realistic preview of my 5 43 2 1 N/A field of interest. • As a result of my internship, I have a better understanding of concepts, theories, and skills in my 5 43 2 1 N/A course of study. • I was given adequate training. 5 43 2 1 N/A • I had regular meetings with my supervisor and 5 43 2 1 N/A received constructive, on-going feedback. • I was provided levels of responsibility consistent with my ability and was given additional 5 43 2 1 N/A responsibility as my experience increased. • My supervisor was available and accessible when I 5 43 2 1 N/A had questions/concerns. • The work I performed was challenging and 5 43 2 1 N/A stimulating. • I was treated on the same level as other employees. 5 43 2 1 N/A • I had a good working relationship with my 5 43 2 1 N/A coworkers. -

How to Develop a Successful Internship

How to Develop a Successful Internship Center for Career Development & Community-Based Learning [email protected] 651-450-3683 2500 80th Street E, Inver Grove Heights, MN 55076 So you are thinking about having an intern? Where do you start? Right here. What Is An Internship? An internship is any carefully monitored work or service experience in which a student has intentional learning goals and reflects actively on what she or he is learning throughout the experience. Characteristics include: • Duration of anywhere from a month to two years, but a typical experience usually lasts from three to six months (a semesters length). • Generally a one time experience. • May be part-time or full-time. • May be paid or non-paid. • Internships may be part of an educational program and carefully monitored and evaluated for academic credit, or internships can be part of a learning plan that someone develops individually. • An important element that distinguishes an internship from a short term job or volunteer work is that an intentional "learning agenda" is structured into the experience. • Learning activities common to most internships include learning objectives, observation, reflection, evaluation and assessment. • An effort is made to establish a reasonable balance between the intern's learning goals and the specific work an organization needs done. • Internships promote academic, career and/or personal development. How Do Internships Benefit Employers? • Year round source of highly motivated pre-professionals • Students bring -

Internship Program

Internship Program District Health Department #10 is a nationally accredited health department, serving 10 counties in northern Michigan. Internships are competitive and open to undergraduate and graduate students. Experience Internships are designed for public health undergraduate and graduate students to gain public health experience in a real world setting that will also benefit the DHD#10 jurisdiction. While the internship is unpaid, the experience is invaluable! Our interns work with a staff member who will supervise and mentor them throughout their time with DHD#10. It is important they have a well-rounded experience; interns DHD#10 has offices in Crawford, work in a designated area but also shadow staff in other Kalkaska, Lake, Manistee, Mason, divisions. In addition, interns are responsible for an Mecosta, Missaukee, Newaygo, individual project, completed with oversight by their Oceana, and Wexford counties. supervisor. Availability of internship A wide variety of public health professionals supervise opportunities are based upon interns, including: program areas, office space, and Nurses staff mentors. Social Workers Health Health Educators Department Dietitians Health Planners Staff “This internship Environmental Health Sanitarians has exceeded my Administrators expectations in the best way possible.” Recommendations from past interns “This internship is “I was told from the “The opportunities start that I wouldn’t not what I expected, I’ve had have given just be doing the me the chance to and I’m actually “typical intern” work. have real life incredibly grateful I am getting actual experiences, for that. I have hands on experiences discover new learned so much in many different passions and things about myself and areas and I absolutely about myself, along love it. -

Code of Professional and Ethical Conduct for Student Interns

Code of Professional and Ethical Conduct for Student Interns General Statements While interning at your site, you are representing not just yourself, but the university and your fellow students, both current and future. Whether you do well or not at your site may have implications far beyond your current situation. You are governed by the employer's employment policies, practices, procedures, dress code, and/or standards of conduct. To avoid any misunderstanding, it is recommended that you obtain clarification regarding such matters from your employer when you begin your assignment. Your performance while on assignment as an intern may be measured by your employer's performance measurement process and/or a university-sponsored performance evaluation. You must receive a satisfactory (or better) performance rating for the period of your internship for the internship to be recognized by the university. You must keep both the University’s Center for Career Development and your sponsoring employer apprised, at all times, of your current e-mail address, physical address and telephone number. You understand that permissible work absences include illness or other serious circumstances. Keeping pace with coursework or co-curricular activities are not legitimate excuses. You will be responsible to notify the employer and your campus Internship Coordinator immediately in case of absence. Any changes in your internship status (layoff, cutback in hours, or dismissal) must be reported immediately to your campus Internship Coordinator. If you feel victimized by a work-related incident (e.g. job misrepresentation, unethical activities, sexual harassment, discrimination, etc.), you are to contact your campus Internship Coordinator immediately.