Closure4 Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a Close Reading of Contemporary Graphic Novels

The Language of Narrative Drawing: a close reading of contemporary graphic novels Abstract: The study offers an alternative analytical framework for thinking about the contemporary graphic novel as a dynamic area of visual art practice. Graphic narratives are placed within the broad, open-ended territory of investigative drawing, rather than restricted to a special category of literature, as is more usually the case. The analysis considers how narrative ideas and energies are carried across specific examples of work graphically. Using analogies taken from recent academic debate around translation, aspects of Performance Studies, and, finally, common categories borrowed from linguistic grammar, the discussion identifies subtle varieties of creative processing within a range of drawn stories. The study is practice-based in that the questions that it investigates were first provoked by the activity of drawing. It sustains a dominant interest in practice throughout, pursuing aspects of graphic processing as its primary focus. Chapter 1 applies recent ideas from Translation Studies to graphic narrative, arguing for a more expansive understanding of how process brings about creative evolutions and refines directing ideas. Chapter 2 considers the body as an area of core content for narrative drawing. A consideration of elements of Performance Studies stimulates a reconfiguration of the role of the figure in graphic stories, and selected artists are revisited for the physical qualities of their narrative strategies. Chapter 3 develops the grammatical concept of tense to provide a central analogy for analysing graphic language. The chapter adapts the idea of the graphic „confection‟ to the territory of drawing to offer a fresh system of analysis and a potential new tool for teaching. -

Aesthetics, Taste, and the Mind-Body Problem in American Independent Comics

PAPER TOWER: AESTHETICS, TASTE, AND THE MIND-BODY PROBLEM IN AMERICAN INDEPENDENT COMICS William Timothy Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2014 William Timothy Jones All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Comics studies, as a relatively new field, is still building a canon. However, its criteria for canon-building has been modeled largely after modernist ideas about formal complexity and criteria for disinterested, detached, “objective” aesthetic judgment derived from one of the major philosophical debates in Western thought: the mind-body problem. This thesis analyzes two American independent comics in order to dissect the aspects of a comic work that allow it to be categorized as “art” in the canonical sense. Chris Ware’s Building Stories is a sprawling, Byzantine comic that exhibits characteristically modernist ideas about the subordination of the body to the mind and art’s relationship to mass culture. Rob Schrab’s Scud: The Disposable Assassin provides a counterpoint to Building Stories in its action-heavy stylistic approach, developing ideas about the merging of the mind and the body and the artistic and the commercial. Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a re -evaluation of comics criticism that values the subjective, emotional, and the popular as much as the “objective” areas of formal complexity and logic. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Anna O’Brien, for the original germ of this idea and hours of enlightening conversation and companionship. To Jeremy Wallach and Esther Clinton, whose emphatic response to the paper that eventually became this thesis was instrumental to my belief in the quality of my work. -

English 5070-WA: Comics and Graphic Narratives

1 English 5070-WA: Comics and Graphic Narratives Course Location: RB 3047 Class Times: Friday, 8:30–11:30am Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 1 Instructor Information ................................................................................................................1 Course Description/Overview ...................................................................................................1 Course Objectives and/or Learner Outcomes ........................................................................1 Course Resources .....................................................................................................................2 Required Course Text(s) ................................................................................................................... 2 Course Website(s) (if applicable) ..................................................................................................... 2 Course Schedule ........................................................................................................................2 Assignments and Evaluation ....................................................................................................5 Assignment Policies ........................................................................................................................... 5 Details of Assignments ..................................................................................................................... -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Course Descriptions Spring 2013 (20131)

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH COURSE DESCRIPTIONS SPRING 2013 (20131) Welcome to the Department of English. For spring semester 2013 we offer a rich selection of introductory and upper-division courses in English and American 105 (Creative Writing for Non-Majors) 32820R 2-4:20 W Bendall literature and culture, as well as Creative Writing workshops. Please feel free to talk to Lawrence Green (director of undergraduate studies), Rebecca Woods In this introductory course we will practice writing and examine trends in three (departmental staff adviser), or other English faculty to help you select the menu genres: non-fiction, poetry, and fiction. Students will complete written work in all of courses that is right for you. of these genres. The work will be discussed in a workshop environment in which lively and constructive participation is expected. We will also read and discuss a All Department of English courses are “R” courses, except for the following variety of work by writers from the required texts. Revisions, reading assignments, “D” courses: ENGL 303, 304, 305, 407, 408, 490, & 496. A Department stamp written critiques, and a final portfolio are required. is not required for “R” course registration prior to the beginning of the semester, but is required for “D” course registration. On the first day of classes all courses will be closed—admission is granted only by the instructor’s signature and the 105 (Creative Writing for Non-Majors) 32821R 2-4:20 TH Solomon Department stamp (available in Taper 404). You must then register in person at the Registration office. Introductory workshop in writing poetry, short fiction and nonfiction for love of the written and spoken word. -

Released 4Th January 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS AUG160126

Released 4th January 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS AUG160126 ASTRO BOY OMNIBUS TP VOL 06 AUG160127 NGE SHINJI IKARI RAISING PROJECT OMNIBUS TP VOL 02 NOV160041 RISE OF THE BLACK FLAME #5 (OF 5) SEP160081 WORLD OF TANKS #4 DC COMICS NOV160198 AQUAMAN #14 NOV160199 AQUAMAN #14 VAR ED NOV160208 BATMAN #14 NOV160209 BATMAN #14 VAR ED OCT160300 CATWOMAN TP VOL 06 FINAL JEOPARDY NOV160214 CYBORG #8 NOV160215 CYBORG #8 VAR ED NOV160295 DC COMICS BOMBSHELLS #21 NOV160298 DEATH OF HAWKMAN #4 (OF 6) NOV160353 EVERAFTER FROM THE PAGES OF FABLES #5 NOV160293 FALL AND RISE OF CAPTAIN ATOM #1 (OF 6) NOV160294 FALL AND RISE OF CAPTAIN ATOM #1 (OF 6) VAR ED NOV160307 FLINTSTONES #7 NOV160308 FLINTSTONES #7 VAR ED OCT160307 GRAYSON TP VOL 05 SPYRALS END NOV160228 GREEN ARROW #14 NOV160229 GREEN ARROW #14 VAR ED OCT160293 GREEN ARROW TP VOL 01 LIFE & DEATH OF OLIVER QUEEN (REBIRTH) NOV160232 GREEN LANTERNS #14 NOV160233 GREEN LANTERNS #14 VAR ED NOV160240 HARLEY QUINN #11 NOV160241 HARLEY QUINN #11 VAR ED NOV160299 INJUSTICE GROUND ZERO #3 NOV160179 JUSTICE LEAGUE #12 (JL SS) NOV160180 JUSTICE LEAGUE #12 VAR ED (JL SS) NOV160183 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA THE ATOM REBIRTH #1 NOV160184 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA THE ATOM REBIRTH #1 VAR ED NOV160163 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) NOV160164 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) CONNER VAR ED NOV160165 JUSTICE LEAGUE SUICIDE SQUAD #3 (OF 6) MADUREIRA VAR ED NOV160302 MIDNIGHTER AND APOLLO #4 (OF 6) NOV160248 NIGHTWING #12 NOV160249 NIGHTWING #12 VAR ED NOV160314 SCOOBY DOO WHERE ARE YOU #77 NOV160279 SHADE -

A Triumph of the Comic-Book Novel December 20, 2012 Gabriel Winslow-Yost Font Size: a a a Building Stories by Chris Ware Pantheon, 260 Pp

A Triumph of the Comic-Book Novel December 20, 2012 Gabriel Winslow-Yost Font Size: A A A Building Stories by Chris Ware Pantheon, 260 pp. boxed set, $50.00 Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware Pantheon, 380 pp., $35.00 The ACME Novelty Library #19 by Chris Ware Drawn and Quarterly/ Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 80 pp., $15.95 The ACME Novelty Library #20 by Chris Ware Drawn and Quarterly/ Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 72 pp., $23.95 The ACME Novelty Library Final Report to Shareholders and Saturday Afternoon Rainy Day Fun Book by Chris Ware Pantheon, 108 pp., $27.50 Quimby the Mouse or, Comic Strips, 1990–1991 by Chris Ware Fantagraphics, 69 pp., $14.95 (paper) Detail from a page of Chris Ware’s Building Stories, showing the ‘girl’ in red at bottom left and the ‘married couple’ on the steps of the building. The top and right of the image show the ‘old lady’ who owns the building, both in the present and in her memories of her younger days. In 1988, Gore Vidal predicted that by 2015 “The New York Review of Comic Books will doubtless replace the old NYR.” It was a joke, of course, and a warning (Vidal preferred “book books,” as he called them), but we’re just a couple of years short now, and he wasn’t all wrong. The past decades have seen an unprecedented amount of serious attention paid to comics, and for good reason: they’re better—stranger, subtler, more ambitious—than ever before. -

Cut-Up and Redrawn: Reading Charles Burns' Swipe Files

AUTHOR PREPRINT VERSION Crucifix, Benoît. “Cut-Up and Redrawn: Reading Charles Burns’ Swipe Files.” Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society 1, no. 3 (2017): 309–33. For citation, refer to the post-print version, which can be downloaded here: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/679770 (or request at benoit.crucifix(a)gmail.com) 1 Cut-Up and Redrawn: Reading Charles Burns’s Swipe Files1 Benoît Crucifix One of Charles Burns’s “most prized possessions,” as displayed in Todd Hignite’s In the Studio, is a scrapbook of comic strip clippings put together by his cartoonist-dilettante father.2 The scrapbook contains a collection of comic strips which he used for reference when drawing: it assembles panels and details clipped out from various newspaper comic strips from the 1940s, such as Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, collecting material that could then be copied and imitated (Figure 1). < Insert Figure 1 here > A collage of comics panels, the scrapbook classifies and arranges them according to topic, size, perspective: it is the model definition of a swipe file, a collection of images cut out from other comics that can then be redrawn into the cartoonist’s own work. Burns’s father’s scrapbook is not an odd piece in comics history. Going back to the nineteenth-century, newspaper readers have assembled scrapbooks archiving their favorite comic strips, a tradition of “writing with scissors” in which the pleasures of rereading and sharing favorite strips resulted in the widespread saving and collating of such material.3 For artists, these -

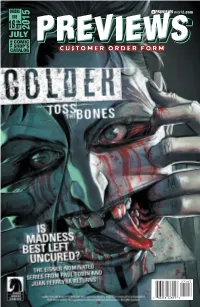

Customer Order Form July

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JULY 2015 JULY COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jul15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 6/4/2015 4:42:12 PM July15 C2 Future Dude.indd 1 6/4/2015 2:33:44 PM COLDER: TEENAGE MUTANT TOSS THE BONES #1 NINJA TURTLES #50 DARK HORSE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN #44 DC COMICS THE PAYBACKS #1 STAR WARS: DARK HORSE COMICS ARTIFACT EDITION HC IDW PUBLISHING TOKYO GHOST #1 IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE SANDMAN: WHITE #1 OVERTURE #6 PLUTONA #1 MARVEL COMICS DC COMICS/VERTIGO IMAGE COMICS July15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 6/4/2015 11:44:21 AM COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Jughead #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed +100 Volume 1 TP/HC l AVATAR PRESS INC Wild’s End: The Enemy Within #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Peanuts: A Tribute to Charles M. Schulz HC l BOOM! STUDIOS Aliens/Vampirella #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Alice Cooper Vs. Chaos #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT FEATURED ITEMS Step Aside Pops: A Hark! A Vagrant Collection HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Usagi Yojimbo: Special Edition SC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Jughead #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Rick & Morty Volume 1 TP l ONI PRESS INC. Crossed +100 Volume 1 TP/HC l AVATAR PRESS INC Doctor Who: The Tenth Doctor Year Two #1 l TITAN COMICS Wild’s End: The Enemy Within #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor Year Two #1 l TITAN COMICS 1 Peanuts: A Tribute to Charles M. -

Released 26Th August

Released 26th August DARK HORSE COMICS JUN150056 CONAN THE AVENGER #17 JUN150013 FIGHT CLUB 2 #4 MAIN MACK CVR JUN150054 HALO ESCALATION #21 JUN150079 HELLBOY IN HELL #7 APR150076 KUROSAGI CORPSE DELIVERY SERVICE OMNIBUS ED TP BOOK 01 JUN150023 MULAN REVELATIONS #3 JUN150015 NEW MGMT #1 MAIN KINDT CVR JUN150021 PASTAWAYS #6 APR150057 SUNDOWNERS TP VOL 02 JUN150022 TOMORROWS #2 APR150043 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LTD ED HC VOL 04 APR150042 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA TP VOL 04 JUN150045 ZODIAC STARFORCE #1 DC COMICS JUN150176 AQUAMAN #43 JUN150241 BATGIRL #43 JUN150249 BATMAN 66 #26 JUN150247 BATMAN ARKHAM KNIGHT GENESIS #1 JUN150182 CYBORG #2 JUN150204 DEATHSTROKE #9 MAY150262 EFFIGY TP VOL 01 IDLE WORSHIP (MR) JUN150188 FLASH #43 MAY150246 GI ZOMBIE A STAR SPANGLED WAR STORY TP JUN150253 GOTHAM BY MIDNIGHT #8 JUN150255 GRAYSON #11 JUN150257 HARLEY QUINN #19 JUN150273 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #9 JUN150203 JLA GODS AND MONSTERS #3 JUN150196 JUSTICE LEAGUE 3001 #3 MAY150242 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK TP VOL 06 LOST IN FOREVER JUN150169 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA #3 JUN150215 PREZ #3 APR150324 SCALPED HC BOOK 02 DELUXE EDITION (MR) JUN150270 SINESTRO #14 JUN150234 SUPERMAN #43 DEC140428 SUPERMAN BATMAN MICHAEL TURNER GALLERY ED HC JUN150221 TEEN TITANS #11 JUN150264 WE ARE ROBIN #3 IDW PUBLISHING JUN150439 ANGRY BIRDS COMICS HC VOL 03 SKY HIGH JUN150446 BEN 10 CLASSICS TP VOL 05 POWERLESS MAY150348 DIRK GENTLYS HOLISTIC DETECTIVE AGENCY #3 JUN150363 DRIVE #1 JUN150431 GHOSTBUSTERS GET REAL #3 JUN150375 GODZILLA IN HELL #2 MAY150423 JOE FRANKENSTEIN HC APR152727 MACHI -

1894-1975 and Building Stories by Ellie Zygmunt a Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduat

Collective Memory in George Sprott: 1894-1975 and Building Stories by Ellie Zygmunt A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts English Memorial University of Newfoundland August 2018 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis examines collective memory in the graphic novels George Sprott: 1894-1975 by Seth and Building Stories by Chris Ware. Seth and Ware illustrate how individual memory is inextricable from collective experiences of history, space, and community by using unconventional publishing formats paired with the visual language of graphic narrative. I argue Seth and Ware also extend the border of collective memory to include the non-fictive space of the reader through multi-media adaptations and collaboration. Seth’s cardboard Dominion models, the chamber oratorio Omnis Temporalis, and Ware’s iPad comic Touch Sensitive create a larger community of memory that extends beyond the page. ii Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the unfailing guidance and patience of Dr. Andrew Loman, and the encouragement of Lars Hedlund. My deepest gratitude for your support of this project. Special thanks to Drawn & Quarterly and Pantheon for permission to include images from George Sprott: 1874-1975 and Building Stories on behalf of Seth (Gregory Gallant) and Chris Ware. iii Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... -

Words and Pictures Along the Line Between Architecture and Comics James Benedict Brown M

The Comic Architect : Words and pictures along the line between architecture and comics James Benedict Brown M. Arch Dissertation Supervised by Dr. Renata Tyszczuk University of Sheffield, October 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sincere thanks to Henk Döll, Ben Katchor and Joost Swarte for giving so much time to be interviewed by this novice interviewer. The executors of the Stephenson Travel Bursary at the University of Sheffield are acknowledged for awarding this project the maximum possible financial support available in 2007 to enable the interviews with Henk Döll, Ben Katchor and Joost Swarte to take place. These interviews are included in their entirety in appendices I, II and III. Dr. Renata Tyszczuk has been a brilliantly stimulating and supportive dissertation tutor, and I would like to thank her for the time, energy and encouragement that she has given to me during this project. The hardback copies of this dissertation were hand bound in Sheffield by Sue Callaghan. For details call (0114) 275 9049. Finally, this dissertation would not be the work that it is were it not for the support and guidance given to me on countless occasions – day and night, in person, by telephone and email – by my closest circle of family, friends and tutors. Thank you MB, RB, SC, RL, BM, RM, SF. CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................... 4 An observation .......................................................................................... 8 Part one: the comic architect .................................................................