Decidedly Uncertain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

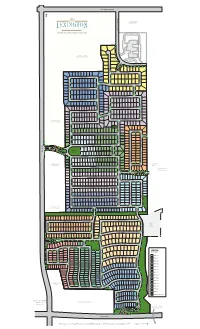

Lexington Phases Mastermap RH HR 3-24-17

ELDORADO PARKWAY MAMMOTH CAVE LANE CAVE MAMMOTH *ZONED FUTURE LIGHT RETAIL MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY MAJESTIC PRINCE CIRCLE MAMMOTH CAVE LANE T IN O P L I A R E N O D ORB DRIVE ARISTIDES DRIVE MACBETH AVENUE MANUEL STREETMANUEL SPOKANE WAY DARK STAR LANE STAR DARK GIACOMO LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDSTONE MANOR GRINDSTONE FUNNY CIDE COURT FUNNY THUNDER GULCH WAY BROKERS TIP LANE MANUEL STREETMANUEL E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND TRAIL LEONATUS LANE LEONATUS PONDER LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTERGREEN DRIVE COIT ROAD COIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD COUNT TURF COUNT DRIVE AMENITY SMARTY JONES STREET CENTER STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD 2 DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY 5 CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 1 Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE FLYING EBONY STREET LIGHT RETAIL Park AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE CONQUISTADOR COURT CONQUISTADOR LUCKY DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY OXBOW AVENUE OXBOW CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 4 WHIRLAWAY DRIVE 9 IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER ROAD C WAR EMBLEM PLACE WAR A N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R I V E 14DUST COMMANDER COURT CIRCLE PASS FORWARD DETERMINE DRIVE SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUIET RD. TIM TAM CIRCLE EASY GOER AVENUE LEGEND PILLORY DRIVE PILLORY BY PHASES HALMA HALMA TRAIL 11 PHASE 1 A PROUD CLAIRON STREET M E MIDDLEGROUND PLACE -

Notice to Licensees

NEVADA GAMING CONTROL BOARD 1919 College Parkway, P.O. Box 8003, Carson City, Nevada 89702 555 E. Washington Avenue, Suite 2600, Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 J. BRIN GIBSON, Chair 3650 S. Pointe Circle, Suite 203, P.O. Box 31109, Laughlin, Nevada 89028 TERRY JOHNSON, Member PHIL KATSAROS, Member 557 W. Silver Street, Suite 207, Elko, Nevada 89801 STEVE SISOLAK 9790 Gateway Drive, Suite 100, Reno, Nevada 89521 Governor 750 Pilot Road, Suite I, Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 NOTICE TO LICENSEES Notice # 2021-35 Issuing Division: Audit DATE: April 28, 2021 TO: All Gaming Licensees and Other Interested Persons FROM: J. Brin Gibson, Chairman SUBJECT: APPROVAL PURSUANT TO REGULATION 22.080 Based on the receipt of multiple applications to the Board under subsection 4 of Nevada Gaming Commission Regulation 22.080, as amended on April 22, 2021, and subject to the conditions set forth in this Industry Notice, the Board grants industry-wide approval to allow licensed race books to use the nationally televised broadcasts on the NBC and NBC Sports Networks to determine winners of or payouts for the following races at Churchill Downs racetrack on April 30, 2021 and May 1, 2021: Date Race Name (Race Number - Stakes Grade) 4/30/21 The Alysheba (Race 6 - Grade II) 4/30/21 The Edgewood (Race 7 - Grade II) 4/30/21 The La Troienne (Race 8 - Grade I) 4/30/21 The Eight Belles (Race 9 - Grade II) 4/30/21 The Twin Spires Turf Sprint (Race 10 - Grade II) 4/30/21 The Longines Kentucky Oaks (Race 11 - Grade I) Date Race Name (Race Number - Stakes Grade) 5/1/21 The Longines Churchill Distaff Turf Mile (Race 6 - Grade II) 5/1/21 The Derby City Distaff (Race 7 - Grade I) 5/1/21 The Pat Day Mile (Race 8 - Grade II) 5/1/21 The American Turf (Race 9 - Grade II) 5/1/21 The Churchill Downs (Race 10 - Grade I) 5/1/21 The Old Forester Bourbon Turf Classic (Race 11 - Grade I) 5/1/21 The Kentucky Derby (Race 12 - Grade I) This approval is subject to the following conditions: 1. -

Santa Anita Derby Santa Anita Derby

Saturday, April 8, 2017 $1,000,000$750,000 SANTA ANITA DERBY SANTA ANITA DERBY EXAGGERATOR Dear Member of the Media: Now in its 82nd year of Thoroughbred racing, Santa Anita is proud to have hosted many of the sport’s greatest moments. Although the names of its historic human and horse heroes may have changed in SANTA ANITA DERBY $1,000,000 Guaranteed (Grade I) the past seven decades of racing, Santa Anita’s prominence in the sport Saturday, April 8, 2017 • Eightieth Running remains constant. Gross Purse: $1,000,000 Winner’s Share: $600,000 This year, Santa Anita will present the 80th edition of the Gr. I, Other Awards: $200,000 second; 120,000 third; $50,000 fourth; $20,000 fifth; $1,000,000 Santa Anita Derby on Saturday, April 8. $10,000 sixth Distance: One and one-eighth miles on the main track The Santa Anita Derby is the premier West Coast steppingstone to Nominations: Early Bird nominations at $500 closed December 26, 2016; the Triple Crown, with 34 Santa Anita Derby starters having won a total Regular nominations close March 25, 2017 by payment of of 40 Triple Crown races. $2,500; Supplementary nominations at $20,000 due at time of entry Track Record: 1:45 4/5, Star Spangled, 5 (Laffit Pincay, Jr., 117, March 24, If you have questions regarding the 2017 Santa Anita Derby, or if 1979, San Bernardino Handicap) you are interested in obtaining credentials, please contact the Publicity Stakes Record: 1:47, Lucky Debonair (Bill Shoemaker, 118, March 6, 1965); Department at your convenience. -

Griffs Cut TV Slate to 13 Games Gollen Farm of Virginia Was

HILLSDALE UPSET Amusements, Pages C-7-9 Features, Page C-12 Music, Page C-10 , Books, Page C-13 Terrdng Wins - Radio, Page C-11 Sundau Ste Sports Garden, Pages C-14-15 C Stretch Duel SIXTEEN PAGES WASHINGTON, D. C„ MARCH 1, 1959 ARCADIA. Call!.. Feb. 38 ¦ played him to win to the tune (AP).—Terrang, a 6-year-old of $193,813. It wagered $4,076.- veteran of racing, captured the 038 on the card. 1145.000 Santa Anita Handicap The Indiana-bred gamester, in a thrilling stretch duel with a 4-year-old, carried 118 3-Length Flamingo today. Victor; the favored Hillsdale pounds, three less than Ter- Troilus As a crowd of 57.000 roared I rang, the third choice in the with excitement. Jockey Bill betting. Boland drove Terrang to vic- It was a photo finish, but it tory and the $97,900 winner’s i was apparent at the finish line net share of the purse for his , that Terrang had beaten the owners, Laurence Pollock and Hoosier favorite. - The margin Roland Bond of was half a length and Royal Texas. Living, Royal Living, from the Llan- . ridden by Manuel Griffs Cut TV Slate to 13 Games gollen Farm of Virginia was . Ycaza, was almost three third. lengths behind in the third spot. nr u hm The time for the mile-and- . mmmm WKMi' , • n winter time one-Quarter clas- | BallyruUah Takes Lead Club Income First Landing sic was 3:00 flat, shy of the * track record of 1.59*, set byr Terrang, always a threat > r*M L Round Table in winning the when pointed for a big stakes, Plunges With ¦ Third Behind raA last year. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

NYCRR Title 9, Executive Subtitle T

Rules and Regulations Chapter I (Division of Horse Racing and Pari-Mutuel Wagering) Subchapter A (Thoroughbred Racing) 9 NYCRR §§ 4000-4082.3 NYCRR Title 9, Executive Subtitle T New York State Gaming Commission Chapter I Division of Horse Racing and Pari-Mutuel Wagering Subchapter A Thoroughbred Racing Article 1 Rules of Racing Part 4000 Article 2 Steeplechases, Hurdle Races and Hunt Meetings Part 4050 Article 3 New York-Bred Thoroughbreds Part 4080 ARTICLE 1 RULES OF RACING Part 4000 General Provisions 4001 Powers and Duties of the Commission 4002 Occupational Licenses 4003 Racing Associations 4004 Transmissions of Information 4005 Association Employees 4006 Racing Employees 4007 Horses 4008 Racing Results 4009 Pari-Mutuel Operation 4010 Pool Calculations 4011 The Daily Double 4012 Possession of Drugs and Drug Testing 4013 [Repealed] 4014 Breeders’ Awards 4020 General Provisions for Race Meetings 4021 Regulations for Race Meeting 4022 The Stewards 4023 Officials of the Meeting 4024 Registration of Horses 4025 Entries, Subscriptions, Declarations and Acceptances for Races 4026 Ownership Rules and Stable Names 4027 Stakes, Subscriptions 4028 Qualifications of Starters 4029 Scale of Weights 4030 Calculating Winnings 1 updated (2/18) Rules and Regulations Chapter I (Division of Horse Racing and Pari-Mutuel Wagering) Subchapter A (Thoroughbred Racing) 9 NYCRR §§ 4000-4082.3 4031 Penalties and Allowances 4032 Apprentice Jockeys and Weight Allowances 4033 Weighing Out 4034 Starting 4035 Rules of the Race 4036 Weighing In 4037 Dead Heats 4038 Claiming Races 4039 Disputes, Objections, Appeals 4040 Restrictions on Jockeys and Stable Employees 4041 Racing Colors and Numbers 4042 Corrupt Practices and Disqualifications of Persons 4043 Drugs Prohibited and Other Prohibitions 4044 Voluntary Exclusion from Racetracks and Restrictions on Telephone Account Wagering 4045 Minimum Penalty Enhancement 4046 Jockey Injury Compensation Fund PART 4000 General Provisions Section 4000.1 Division of rules 4000.2 Powers reserved 4000.3 Definitions 4000.4 [Repealed] § 4000.1. -

Alibhai-GB (By Hyperion-GB, 1938) – Determine (1954) Alydar (By

SIRES Pioneerof the Nile (by Empire Maker, 2006) – American Pharoah (2015) Polish Navy (by Danzig, 1984) – Sea Hero (1993) +Ponder (by Pensive, 1946) – Needles (1956) Alibhai-GB (by Hyperion-GB, 1938) – Determine (1954) Pretendre-GB (by Doutelle-GB, 1963) – Canonero II (1971) Alydar (by Raise a Native, 1975) – Alysheba (1987) & Strike the Gold (1991) Quiet American (by Fappiano, 1986) – Real Quiet (1998) At the Threshold (by Norcliffe-CAN, 1981) – Lil E. Tee (1992) Raise a Native (by Native Dancer, 1961) – Majestic Prince (1969) Australian-GB (by West Australian-GB, 1858) – Baden-Baden (1877) Reform (by Leamington-GB, 1871) – Azra (1892) Birdstone (by Grindstone, 2001) – Mine That Bird (2009) +Reigh Count (by Sunreigh-GB, 1925) – Count Fleet (1943) Black Toney (by Peter Pan, 1911) – Black Gold (1924) & Brokers Tip (1933) Royal Coinage (by Eight Thirty, 1952) – Venetian Way (1960) Blenheim II-GB (by Blandford-IRE, 1927) – Whirlaway (1941) & Jet Pilot (1947) Royal Gem II-AUS (by Dhoti-GB, 1942) – Dark Star (1953) Bob Miles (by Pat Malloy, 1881) – Manuel (1899) @Runnymede (by Voter-GB, 1908) – Morvich (1922) Bodemeister (by Empire Maker, 2009) – Always Dreaming (2017) Saggy (by Swing and Sway, 1945) – Carry Back (1961) Bold Bidder (by Bold Ruler, 1962) – Cannonade (1974) & Spectacular Bid (1979) Scat Daddy (by Johannesburg, 2004) – Justify (2018) Bold Commander (by Bold Ruler, 1960) – Dust Commander (1970) Sea King-GB (by Persimmon-GB, 1905) – Paul Jones (1920) Bold Reasoning (by Boldnesian, 1968) – Seattle Slew (1977) +Seattle Slew (by Bold Reasoning, 1974) – Swale (1984) Bold Ruler (by Nasrullah-GB, 1954) – Seattle Slew (1973) Silver Buck (by Buckpasser, 1978) – Silver Charm (1997) +Bold Venture (by St. -

Soring-Bookiet-March-2014.Pdf

5/2015 Table of Contents Executive Summary 2 Factsheet 6 Visual Summary 8 Endorsements for the Prevent All Soring Tactics (PAST) Act 33 AAEP White Paper 36 AVMA-AAEP Joint Statement on Action Devices and Performance Packages 43 Useful Contacts 44 Additional Information 45 1 WHAT IT IS AND WHY IT’S DONE During the late 1940s and 1950s Tennessee Walking Horses surged in popularity with the general public, and those with an exaggerated gait proved to be particularly attractive. Some horses that were “lite shod” could achieve such a gait with extensive training; however, as the “big lick” caught judges’ fancy, trainers started using other practices to enhance movement. Weighted shoes, stacked pads, and weighted chains began to appear, and the methods quickly became more aggressive—heavier weights and chains, objects (e.g., tacks) placed against the sole of the hoof to induce pain, and the application of caustic substances on the pastern or coronary band to induce pain when those areas were rubbed with chain or roller bracelets. These aggressive practices are called “soring” and the result is a horse that snatches its forelimbs off the ground to alleviate pain, and brings its hind limbs under itself as far as possible to reduce weight on the forelimbs. HOW IT'S DONE Chemical agents (e.g., kerosene, diesel or croton oil, hand cleaners, WD 40, oil of mustard, cinnamon oil, other caustic substances) are applied to the pastern and coronary band region. Then bracelet-like chains or rollers (“action devices”) are attached around the front of the pastern to rub against the skin and exacerbate the pain caused by the caustic agents. -

RUNNING STYLE at Quarter Mile Decidedly 1962 9 9 ¼ Carry Back 1961 11 18

RUNNING STYLE At Quarter Mile Decidedly 1962 9 9 ¼ Carry Back 1961 11 18 Venetian Way 1960 4 3 ½ Wire-To-Wire Kentucky Derby Winners : Horse Year Call Lengths Tomy Lee 1959 2 1 ½ American Pharoah 2015 3 1 Tim Tam 1958 8 11 This listing represents 22 Kentucky Derby California Chrome 2014 3 2 Iron Liege 1957 3 1 ½ winners that have led at each point of call during the Orb 2013 16 10 Needles 1956 16 15 race. Points of call for the Kentucky Derby are a I’ll Have Another 2012 6 4 ¼ quarter-mile, half-mile, three-quarter-mile, mile, Swaps 1955 1 1 Animal Kingdom 2011 12 6 Determine 1954 3 4 ½ stretch and finish. Super Saver 2010 6 5 ½ From 1875 to 1959 a start call was given for Dark Star 1953 1 1 ½ Mine That Bird 2009 19 21 Hill Gail 1952 2 2 the race, but was discontinued in 1960. The quarter- Big Brown 2008 4 1 ½ Count Turf 1951 11 7 ¼ mile then replaced the start as the first point of call. Street Sense 2007 18 15 Middleground 1950 5 6 Barbaro 2006 5 3 ¼ Ponder 1949 14 16 Wire-to-Wire Winner Year Giacomo 2005 18 11 Citation 1948 2 6 Smarty Jones 2004 4 1 ¾ War Emblem 2002 Jet Pilot 1947 1 1 ½ Funny Cide 2003 4 2 Winning Colors-f 1988 Assault 1946 5 3 ½ War Emblem 2002 1 ½ Spend a Buck 1985 Hoop Jr. 1945 1 1 Monarchos 2001 13 13 ½ Bold Forbes 1976 Pensive 1944 13 11 Riva Ridge 1972 Fusaichi Pegasus 2000 15 12 ½ Count Fleet 1943 1 head Kauai King 1966 Charismatic 1999 7 3 ¾ Shut Out 1942 4 2 ¼ Jet Pilot 1947 Real Quiet 1998 8 6 ¾ Whirlaway 1941 8 15 ½ Silver Charm 1997 6 4 ¼ Count Fleet 1943 Gallahadion 1940 3 2 Grindstone 1996 15 16 ¾ Bubbling Over 1926 Johnstown 1939 1 2 Thunder Gulch 1995 6 3 Paul Jones 1920 Lawrin 1938 5 7 ½ Go for Gin 1994 2 head Sir Barton 1919 War Admiral 1937 1 1 ½ Sea Hero 1993 13 10 ¾ Regret-f 1915 Bold Venture 1936 8 5 ¾ Lil E. -

Derby Day Weather

Derby Day Weather (The following records are for the entire day...not necessarily race time...unless otherwise noted. Also, the data were taken at the official observation site for the city of Louisville, not at Churchill Downs itself.) Coldest Minimum Temperature: 36 degrees May 4, 1940 and May 4, 1957 Coldest Maximum Temperature: 47 degrees May 4, 1935 and May 4, 1957* (record for the date) Coldest Average Daily Temperature: 42 degrees May 4, 1957 Warmest Maximum Temperature: 94 degrees May 2, 1959 Warmest Average Daily Temperature: 79 degrees May 14, 1886 Warmest Minimum Temperature: 72 degrees May 14, 1886 Wettest: 3.15" of rain May 5, 2018 Sleet has been recorded on Derby Day. On May 6, 1989, sleet fell from 1:01pm to 1:05pm EDT (along with rain). Snow then fell the following morning (just flurries). *The record cold temperatures on Derby Day 1957 were accompanied by north winds of 20 to 25mph! Out of 145 Derby Days, 69 experienced precipitation at some point during the day (48%). Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (24-hr): 7 (2007-2013) Longest stretch of consecutive wet Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 6 (1989 - 1994) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (24-hr): 12 (1875-1886) Longest stretch of consecutive dry Derby Days (1pm-7pm): 12 (1875 - 1886) For individual Derby Day Weather, see next page… Derby Day Weather Date High Low 24-hour Aftn/Eve Weather Winner Track Precipitation Precipitation May 4, 2019 71 58 0.34” 0.34” Showers Country House Sloppy May 5, 2018 70 61 3.15” 2.85” Rain Justify Sloppy May 6, 2017 62 42 -

The White Horse Press Full Citation: Cederlöf, Gunnel

The White Horse Press Full citation: Cederlöf, Gunnel. "Narratives of Rights: Codifying People and Land in Early Nineteenth-Century Nilgiris." Environment and History 8, no. 3 (August 2002): 319–62. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3131. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2002. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this article may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. Narratives of Rights: Codifying People and Land in Early Nineteenth-Century Nilgiris1 GUNNEL CEDERLÖF Dept of History and Dept of Cultural Anthropology and Ethnology Trädgårdsgatan 18 753 09 Uppsala, Sweden Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article has two aims. Firstly, it analyses how multi-faceted narratives of south Indian people as communities and their rights in land and resources were established in early European reports from the Nilgiris. These narratives were gradually accommodated in increasingly racial interpretations of Indian society from the 1860s onwards. These became established in the state-produced historiographies at the turn of the century, and have even been repeated by social scientists up to the present day. Secondly, it focuses upon how ethnologically- derived categories influenced the codification of people in the Nilgiris, and how this process interacted with the legal codification of peoples’ access to land and natural resources. KEY WORDS India, colonialism – India, forest, anthropology – history, legal rights – nine- teenth century – India, indigenous people – history When officers of the British East India Company first entered the Nilgiri hills to establish settlements in the Western Ghats, they found themselves in the midst of disputes over rights in forest lands. -

LOCKED in BATTLE Haskell Looms a Grade 1 Rematch of Louisiana Derby See Page 3

THURSDAY, JULY 15, 2021 BLOODHORSE.COM/DAILY HODGES PHOTOGRAPHY/ALEXANDER BARKOFF HODGES PHOTOGRAPHY/ALEXANDER LOCKED IN BATTLE Haskell Looms a Grade 1 Rematch of Louisiana Derby See page 3 IN THIS ISSUE 8 Baffert Granted Injunction to Race at NYRA Tracks 14 Fasig-Tipton Publishes Catalog for 100th Saratoga Sale 16 Nearly Two Years Later, Fans Can Return to Saratoga BLOODHORSE DAILY Download the FREE smartphone app PAGE 1 OF 41 CONTENTS 3 Haskell Looms a Grade 1 Rematch of Louisiana Derby 25 Funstar Sets Record for Online Sale Price 7 Leading Sires of Yearlings by Average 27 Hurricane Lane Annihilates Field in Grand Prix de Paris 8 Baffert Granted Injunction to Race at NYRA Tracks 28 Bobby’s Kitten Off the Mark 11 Seven First-Crop Sires With Six-Figure July Averages With Lone Australian Crop 14 Fasig-Tipton Publishes Catalog for 100th Saratoga Sale 29 Alysheba Grew Better With Age 15 Breeders’ Cup Announces Board Election Results 30 Results & Entries 16 Nearly Two Years Later, Fans Can Return to Saratoga 20 Happy Soul Tops Schuylerville at Saratoga 22 Speedy Golden Pal Returns in Quick Call at Saratoga 23 H-2B Visa Program Faces Threat From Appropriations Bill 24 Belmont Park All-Sources Handle Rises 20% From 2019 SKIP DICKSTEIN TAA a ccreditation: The G o l d S t a n d a r d in aftercare. A publication of The Jockey Club Information Systems, Inc. and TOBA Media Properties, Inc. ON THE COVER Hot Rod Charlie (rail) turns for home ahead of Editorial Director General Manager Midnight Bourbon (center) and Mandaloun in the Claire Crosby Scott Carling Louisiana Derby at Fair Grounds Race Course Visuals Director Digital Media Manager Anne M.