Mountain Film. an Analysis of the History and Characteristics of a Documentary Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitre Peak Guided Ascent Trip Notes 2021/22

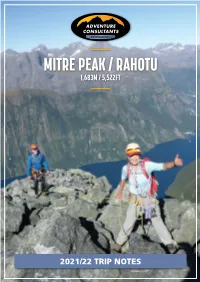

MITRE PEAK / RAHOTU 1,683M / 5,522FT 2021/22 TRIP NOTES MITRE PEAK TRIP NOTES 2021/22 TRIP DETAILS Dates: Available on demand January to April Duration: 5 days Departure: ex Wanaka, New Zealand Price: NZ$6,300 per person Mitre Peak is an exhilarating climb from sea level. Photo: Lydia Bradey Situated above the languid waters of Milford Sound, Mitre Peak is one of New Zealand’s most iconic mountains. We climb the South East Ridge, a razor-sharp ridge that appears like a giant sleeping dragon’s tail as we make our way along to the pointed summit apex. And finally, the summit; as spectacular a view as one THE ROUTE will ever be fortunate enough to see. The sun reflects off the Tasman Sea directly to the west while the The programme starts with ascents around the Homer spectacular granite and glaciated peaks of the Darran Tunnel region where we warm up with a plethora of Mountains stimulate the visual senses when we gaze to good climbing options to choose from. The variety the east. extends from classic alpine ascents to an ascent of one of the established ‘trad’ rock routes through to sport After we spend time soaking up the views we begin climbing routes so there’s something for everyone. the descent along the route by which we have come, content with a well-deserved summit. When the weather allows, we drop down to Milford Sound to make our attempt on Mitre Peak. If the ocean is smooth, we may paddle kayaks across the bay or PREREQUISITE SKILLS alternatively, we take a short helicopter flight to the start of the climb. -

Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre

Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications- Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 229-258 Perceptual Realism and Embodied Experience in the Travelogue Genre By Perla Carrillo Quiroga This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the This paper draws two lines of analysis. On the one hand it discusses the history of the travelogue genre while drawing a parallel with a Bazanian teleology of cinematic realism. On the other, it incorporates phenomenological approaches with neuroscience’s discovery of mirror neurons and an embodied simulation mechanism in order to reflect upon the techniques and cinematic styles of the travelogue genre. In this article I discuss the travelogue film genre through a phenomenological approach to film studies. First I trace the history of the travelogue film by distinguishing three main categories, each one ascribed to a particular form of realism. The hyper-realistic travelogue, which is related to a perceptual form of realism; the first person travelogue, associated with realism as authenticity; and the travelogue as a traditional documentary which is related to a factual form of realism. I then discuss how these categories relate to Andre Bazin’s ideas on realism through notions such as montage, duration, the long take and his "myth of total cinema". I discuss the concept of perceptual realism as a key style in the travelogue genre evident in the use of extra-filmic technologies which have attempted to bring the spectator’s body closer into an immersion into filmic space by simulating the physical and sensorial experience of travelling. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit

Amazon Adventure 3D Press Kit SK Films: Facebook/Instagram/Youtube: Amber Hawtin @AmazonAdventureFilm Director, Sales & Marketing Twitter: @SKFilms Phone: 416.367.0440 ext. 3033 Cell: 416.930.5524 Email: [email protected] Website: www.amazonadventurefilm.com 1 National Press Release: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AMAZON ADVENTURE 3D BRINGS AN EPIC AND INSPIRATIONAL STORY SET IN THE HEART OF THE AMAZON RAINFOREST TO IMAX® SCREENS WITH ITS WORLD PREMIERE AT THE SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY ON APRIL 18th. April 2017 -- SK Films, an award-winning producer and distributor of natural history entertainment, and HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, the acclaimed film production unit of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, announced today the IMAX/Giant Screen film AMAZON ADVENTURE will launch on April 18, 2017 at the World Premiere event at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. The film traces the extraordinary journey of naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates - the most influential scientist you’ve never heard of – who provided “the beautiful proof” to Charles Darwin for his then controversial theory of natural selection, the scientific explanation for the development of life on Earth. As a young man, Bates risked his life for science during his 11-year expedition into the Amazon rainforest. AMAZON ADVENTURE is a compelling detective story of peril, perseverance and, ultimately, success, drawing audiences into the fascinating world of animal mimicry, the astonishing phenomenon where one animal adopts the look of another, gaining an advantage to survive. "The Giant Screen is the ideal format to take audiences to places that they might not normally go and to see amazing creatures they might not normally see,” said Executive Producer Jonathan Barker, CEO of SK Films. -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174 -

CONSIGNES Semaine Du 23 Au 27 Mars Travail À Faire Sur La

CONSIGNES Semaine du 23 au 27 mars Travail à faire sur la thématique des films Pour suivre le cours de cette semaine voici les étapes à suivre : 1- D’abord, vous lisez attentivement la trace écrite en page 2 puis vous la recopiez dans votre cahier. 2- Ensuite, vous compléter au crayon à papier la fiche en page 3. Pour faire cela, vous devez d’abord lire toutes les phrases à trou puis lire chaque proposition et ensuite essayez de compléter les trous. 3- Pour terminer, vous faites votre autocorrection grâce au corrigé qui se trouve en page 4 1 Monday, March 23rd Objectif : Parler des films Film vocabulary I know (vocabulaire de film que je connais) : - film (UK) / movie (USA) - actor = acteur / actress = actrice - a trailer = une bande annonce - a character = un personnage 1. Different types of films - Activity 2 a 1 page 66 (read, listen and translate the film types) An action film = un film d’action / a comedy = une comédie / a drama = un drame / an adventure film = un film d’aventure / an animation film = un film d’animation = un dessin animé / a fantasy film = un film fantastique / a musical = une comédie musicale/ a spy film = un film espionnage / a horror film = un film d’horreur / a science fiction film = un film de science fiction. - Activity 2 a 2 page 66 (listen to the film critic and classify the films) Johnny English Frankenweenie The Hobbit Les Misérables The Star Wars Reborn (French) series - A comedy, - An animation - A fantasy film - a musical - the series are film, science fiction - An action film - an adventure - a drama films and and - A comedy and film - adventure films - A spy film - A horror film 2. -

Filmography 1963 Through 2018 Greg Macgillivray (Right) with His Friend and Filmmaking Partner of Eleven Years, Jim Freeman in 1976

MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography 1963 through 2018 Greg MacGillivray (right) with his friend and filmmaking partner of eleven years, Jim Freeman in 1976. The two made their first IMAX Theatre film together, the seminal To Fly!, which premiered at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum on July 1, 1976, one day after Jim’s untimely death in a helicopter crash. “Jim and I cared only that a film be beautiful and expressive, not that it make a lot of money. But in the end the films did make a profit because they were unique, which expanded the audience by a factor of five.” —Greg MacGillivray 2 MacGillivray Freeman Films Filmography Greg MacGillivray: Cinema’s First Billion Dollar Box Office Documentarian he billion dollar box office benchmark was never on Greg MacGillivray’s bucket list, in fact he describes being “a little embarrassed about it,” but even the entertainment industry’s trade journal TDaily Variety found the achievement worth a six-page spread late last summer. As the first documentary filmmaker to earn $1 billion in worldwide ticket sales, giant-screen film producer/director Greg MacGillivray joined an elite club—approximately 100 filmmakers—who have attained this level of success. Daily Variety’s Iain Blair writes, “The film business is full of showy sprinters: filmmakers and movies that flash by as they ring up impressive box office numbers, only to leave little of substance in their wake. Then there are the dedicated long-distance specialists, like Greg MacGillivray, whose thought-provoking documentaries —including EVEREST, TO THE ARCTIC, TO FLY! and THE LIVING Sea—play for years, even decades at a time. -

Sims Reed Ltd. AUTUMN

Sims Reed Ltd. AUTUMN - 2 0 2 0 - 1. CHARLES I. The Most Remarkable Transactions of the Reign of Charles I. London. Printed & Sold by Thos. & John Bowles Printsellers. 1727 / 1728. Oblong folio. (474 x 616 mm). [10 unnumbered leaves]. 10 large etchings with engraving on thick laid paper, each with title in English and French and parallel explanatory text by various engravers after various artists (see below), the first two etchings with publisher's details at head; sheet size: 468 x 608 mm. Contemporary straight-grained red morocco, front and rear boards with highly elaborate decorative tooled borders with larger tooled corner pieces to surround large central astral vignette com- posed of small astral tools, banded spine in 14 compartments with elaborate decorative tooling and gilt presentation, marbled endpapers, a.e.g. A remarkable complete set of excellent impressions of the rare series of plates illustrating the life of Charles I, here in a superlative decorative presentation binding of contemporary red morocco. This series, presented from a strongly sympathetic royalist perspective, depicts 10 tableaux from the life of Charles I, be- ginning with his marriage to Henrietta Maria of France in 1625 and concluding with his execution and, pace the title of the plate, his Apotheosis. Even if the images themselves did not stress the romantic tragedy, the engraved text beneath each - in English for a domestic and French for a continental audience - provides ample detail concerning the sufferings of the mis- understood, otherworldly and much put upon Royal Martyr. Bathos (pathos!) aside, the series in nevertheless a triumph of engraving, a superb example of pictorial biography and several of the plates are superlative masterpieces of invention. -

The Stage of the Mountains

Leopold- Franzens Universität Innsbruck The Stage of the Mountains A TRANSNATIONAL AND HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE MOUNTAINS AS A STAGE IN 100 YEARS OF MOUNTAIN CINEMA Diplomarbeit Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Mag. phil. an der Philologisch- Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Eingereicht bei PD Mag. Dr. Christian Quendler von Maximilian Büttner Innsbruck, im Oktober 2019 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister- /Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. ______________________ ____________________________ Datum Unterschrift Table of Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Mountain Cinema Overview ................................................................................................... 4 The Legacy: Documentaries, Bergfilm and Alpinism ........................................................... 4 Bergfilm, National Socialism and Hollywood -

From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 16 (2019) 59–79 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2019-0004 From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The films of Guy Maddin, from his debut feature Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) to his most recent one, The Forbidden Room (2015), draw extensively on the visual vocabulary and narrative conventions of 1920s and 1930s German cinema. These cinematic revisitations, however, are no mere exercise in sentimental cinephilia or empty pastiche. What distinguishes Maddin’s compulsive returns to the era of German Expressionism is the desire to both archive and awaken the past. Careful (1992), Maddin’s mountain film, reanimates an anachronistic genre in order to craft an elegant allegory about the apprehensions and anxieties of everyday social and political life. My Winnipeg (2006) rescores the city symphony to reveal how personal history and cultural memory combine to structure the experience of the modern metropolis, whether it is Weimar Berlin or wintry Winnipeg. In this paper, I explore the influence of German Expressionism on Maddin’s work as well as argue that Maddin’s films preserve and perpetuate the energies and idiosyncrasies of Weimar cinema. Keywords: Guy Maddin, Canadian film, German Expressionism, Weimar cinema, cinephilia. Any effort to catalogue completely the references to, and reanimations of, German Expressionist cinema in the films of Guy Maddin would be a difficult, if not impossible, task. From his earliest work to his most recent, Maddin’s films are suffused with images and iconography drawn from the German films of the 1920s. -

Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview and Major Papers 4-2009 Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Peirce, Merle Kenneth, "Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films" (2009). Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview. 19. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSGRESSIVE MASCULINITIES IN SELECTED SWORD AND SANDAL FILMS By Merle Kenneth Peirce A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Individualised Masters' Programme In the Departments of Modern Languages, English and Film Studies Rhode Island College 2009 Abstract In the ancient film epic, even in incarnations which were conceived as patriarchal and hetero-normative works, small and sometimes large bits of transgressive gender formations appear. Many overtly hegemonic films still reveal the existence of resistive structures buried within the narrative. Film criticism has generally avoided serious examination of this genre, and left it open to the purview of classical studies professionals, whose view and value systems are significantly different to those of film scholars. -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema.