The Deified Celebrity: Understanding Representations Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upendra (Actor) Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Upendra (actor) 电影 串行 (大全) S/O Satyamurthy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/s%2Fo-satyamurthy-16254994/actors Kanyadanam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kanyadanam-16250143/actors Hollywood https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hollywood-15048661/actors Uppi Dada M.B.B.S. https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/uppi-dada-m.b.b.s.-7899084/actors Preethse https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/preethse-7239771/actors Super Star https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/super-star-7642802/actors Naanu Naane https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/naanu-naane-16252037/actors Mukunda Murari https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mukunda-murari-26963162/actors Superro Ranga https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/superro-ranga-17082037/actors Anatharu https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/anatharu-4752039/actors Rajani https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rajani-28180133/actors Dubai Babu https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dubai-babu-5310505/actors Kutumba https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kutumba-6448652/actors Gowramma https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gowramma-5590114/actors Gokarna https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gokarna-5578039/actors Omkara https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/omkara-7090236/actors Raa https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/raa-7278365/actors Auto Shankar https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/auto-shankar-4826123/actors Arakshaka https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/arakshaka-4783859/actors News https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/news-16957621/actors -

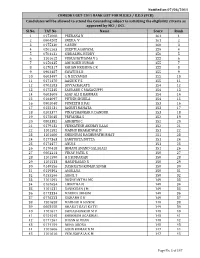

Rank List to Be Published in Web Final

Notified on 07/06/2011 COMEDK UGET2011 RANK LIST FOR M.B.B.S / B.D.S (PCB) Candidates will be allowed to attend the Counseling subject to satisfying the eligibility criteria as approved by MCI / DCI. Sl.No. TAT No Name Score Rank 1 0172008 PRERANA N 161 1 2 0804505 SNEHA V 161 2 3 0175330 S ARUN 160 3 4 0501263 DEEPTI AGARWAL 159 4 5 0704132 SIDDALING REDDY 156 5 6 1101615 PURUSHOTHAMA V S 155 6 7 0150435 ABHISHEK KUMAR 155 7 8 0170317 ROHAN KRISHNA C R 155 8 9 0902487 SWATHI S B 155 9 10 0603497 G N DEVAMSH 155 10 11 0171470 AASHIK Y S 155 11 12 0702583 DIVYACRAGATE 154 12 13 0175345 SAURABH C MASAGUPPI 154 13 14 0603609 ASAF ALI K KAMMAR 154 14 15 0164097 PIYUSH SHUKLA 154 15 16 0902048 PUNEETH K PAI 153 16 17 0155131 JAGRITI NAHATA 153 17 18 0203377 VINAYSHANKAR R DANDUR 153 18 19 0175045 PRIYANKA S 152 19 20 0803382 ABHIJITH C 152 20 21 0179132 VENKATESH AKSHAY RAAG 152 21 22 1101582 MADHU BHARADWAJ N 151 22 23 1101600 SHRINIVAS RAGHUPATHI BHAT 151 23 24 0177363 SAMYUKTA DUTTA 151 24 25 0174477 ANUJ S 151 25 26 0170418 HIMANI ANAND GALAGALI 151 26 27 0602214 VINAY PATIL S 150 27 28 1101590 H S SIDDARAJU 150 28 29 1101533 HARIPRASAD R 150 29 30 0149556 DASHRATH KUMAR SINGH 150 30 31 0159392 AMULLYA 150 31 32 0155266 AKHIL S 150 32 33 1101592 DUSHYANTHA MC 149 33 34 0167654 LIKHITHA N 149 34 35 1101531 RAVIKIRAN J M 149 35 36 0173334 MARINA AKHAM 149 36 37 0176223 RISHABH R K 149 37 38 1201628 MADHAV H HANDE 149 38 39 0603558 BHARAT RAVI KATTI 149 39 40 1101617 SHIVASHANKAR M V 148 40 41 0154545 SHUBHAM AGARWAL 148 41 42 0171261 SUSAN KURIAN 148 42 43 0174159 NEHA ARORA 148 43 44 1101606 ARUN KUMAR N M 147 44 45 1101616 VENUGOPALA K M 147 45 Page No. -

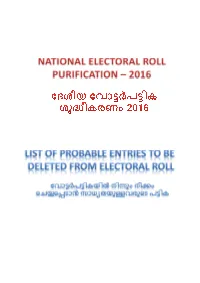

Probable Deletions (PDF

LIST OF PROBABLE ENTRIES IDENTIFIED TO BE DELETED FROM ELECTORAL ROLL DISTRICT NO & NAME :- 8 ERNAKULAM LAC NO & NAME :- 81 THRIPUNITHURA STATUS - S- SHIFT, E-EXPIRED , R- REPLICATION, M-MISSING, Q-DISQUALIFIED. LIST OF PROBABLE ENTRIES IDENTIFIED TO BE DELETED FROM ELECTORAL ROLL DISTRICT NO & NAME :- 8 ERNAKULAM LAC NO & NAME :- 81 THRIPUNITHURA PS NO & NAME :- 1 J.B.S Kundannoor (East side of Main Building) SL.NO NAME OF ELECTOR RLN RELATION NAME SEXAGEIDCARD_NO STATUS 3 Kevin J Pallan F Joyson M 22AFJ0317495 S 4 Lalitha H Purushan F 64KL/11/074/501616 S 5 Viju Kumar P P F Purushan M 40JGQ1509991 E 9 Mini H Surendran F 33JGQ1826536 R 23 Vimal N V F Varghese M 23AFJ0580050 R 41 Anilatmajan F Sivasankaran M 52KL/11/074/501064 S 42 Prameela H Anilatmajan F 45KL/11/074/501386 S 43 Akhil P A F Anilathmajan M 25AFJ0181446 S 44 Vanitha Babu F Babu Gopalan F 23AFJ0214544 R 76 Nalini H Sreedharan F 81KL/11/074/501463 E 104 Sanitha Sabu F Sabu F 24AFJ0279364 R 105 Chakkammu H Kocheetto F 84KL/11/074/501497 E 150 Karthikeyan F Ayichan M 79KL/11/074/501320 E 205Karuppan F Koran M 82KL/11/074/501618 E 225 ribin raj .P M regini.K.T M 25AFJ0193110 S 250 Mary Michael H Michael F 60AFJ0211797 S 280 Prabhakaran F Sankaran M 63KL/11/074/501101 S 281 Anandavalli H Prabhakaran F 57KL/11/074/501267 S 368 Govindharam K F Krishnan M 26AFJ0131110 S 382 Delish Raymond F Raymond M 24AFJ0181586 S 402Vimal F Viswanathan M 28JGQ1366806 S 403Vipin K.A. -

Hospital List for Medicare Under Health Insurance| Royal Sundaram

SL.N STD O. HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS - 1 ADDRESS - 2 CITY PIN CODE STATE ZONE CODE TEL 1 TEL - 2 FAX - 1 SALUTATION FIRST NAME MIDDLE SURNAME E MAIL ID (NEAR PEERA 1 SHRI JIYALAL HOSPITAL & MATERNITY CENTRE 6, INDER ENCLAVE, ROHTAK ROAD GARHI CHOWK) DELHI 110 087 DELHI NORTH 011 2525 2420 2525 8885 MISS MAHIMA 2 SUNDERLAL JAIN HOSPITAL ASHOK VIHAR, PHASE II DELHI 110 052 DELHI NORTH 011 4703 0900 4703 0910 MR DINESH K KHANDELWAL 3 TIRUPATI STONE CENTRE & HOSPITAL 6,GAGAN VIHAR,NEW DELHI DELHI 110051 DELHI NORTH 011 22461691 22047065 MS MEENU # 2, R.B.L.ISHER DAS SAWHNEY MARG, RAJPUR 4 TIRATH RAM SHAH HOSPITAL ROAD, DELHI 110054 DELHI NORTH 011 23972425 23953952 MR SURESH KUMAR 5 INDRAPRASTHA APOLLO HOSPITALS SARITA VIHAR DELHI MATHURA ROAD DELHI 110044 DELHI NORTH 011 26925804 26825700 MS KIRAN 6 SATYAM HOSPITAL A4/64-65, SECTOR-16, ROHINI, DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27850990 27295587 DR VIJAY KOHLI CS / OCF - 6 (NEAR POPULAR APARTMENT AND SECTOR - 13, 7 BHAGWATI HOSPITAL MOTHER DIARY BOOTH) ROHINI DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27554179 27554179 DR NARESH PAMNANI NETRAYATAN DR. GROVER'S CENTER FOR EYE 8 CARE S 371, GREATER KAILASH 2 DELHI 110 048 DELHI NORTH 011 29212828 29212828 DR VISHAL GROVER 9 SHROFF EYE CENTRE A-9, KAILASH COLONY DELHI 110048 DELHI NORTH 011 29231296 29231296 DR KOCHAR MADHUBAN 10 SAROJ HOSPITAL & HEART INSTITUTE SEC-14, EXTN-2, INSTITUTIONAL AREA CHOWK DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27557201 2756 6683 MR AJAY SHARMA 11 ADITYA VARMA MEDICAL CENTRE 32, CHITRA VIHAR DELHI 110 092 DELHI NORTH 011 2244 8008 22043839 22440108 MR SANOJ GUPTA SWARN CINEMA 12 SHRI RAMSINGH HOSPTIAL AND HEART INSTITUTE B-26-26A, EAST KRISHNA NAGAR ROAD DELHI 110 051 DELHI NORTH 011 209 6964 246 7228 MS ARCHANA GUPTA BALAJI MEDICAL & DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH 13 CENTRE 108-A, I.P. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU -

NEET PG Rank Wise List of Candidates Who Studied MBBS in the State of Andhra Pradesh and Appeared for NEET PG -2019 Conducted by NBE

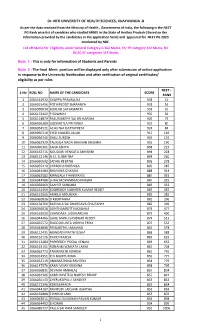

Dr.NTR UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES: ANDHRAPRADESH: VIJAYAWADA -8 As per the data received from the Ministry of Health, Government of India, the following is the NEET PG Rank wise list of candidates who studied MBBS in the State of Andhra Pradesh and appeared for NEET PG -2019 conducted by NBE. This is only for information of Students and Parents Note : The final merit position will be displayed only after submission of online application in response to the University Notification and after verification of original certificates /eligibility as per rules NEET - S.NO PG 2019 ROLLNO SCORE NAME OF THE CANDIDATE RANK 1 13 1966051550 946 MUGADA CHANDRASEKHAR 2 120 1966144183 890 PANUGANTI.HIMA BINDU 3 127 1966144828 889 VARIGONDA MAHIDHAR 4 132 1966080869 887 MASINENI RAGASUDHA 5 135 1966012765 886 ALLU RAMYA DEVI 6 214 1966119878 873 S SRINIVASA AKHIL ANIRUDH 7 235 1966143663 870 KAMBHAMPATI SREE LEKHA 8 265 1966048062 866 GADEKARI VAISHNAVI 9 267 1966144717 866 TANNERU RAGA SAI PRUDHVI RAJU 10 286 1966047421 864 DAMALAPATI VENKATESH 11 361 1966038453 857 LELLA AKHIL ROHAN 12 383 1966055987 854 TEJASWI VINJAM 13 397 1966038578 853 LAKSHMI SRUTHA KEERTHI MEDAGAM 14 401 1966055714 852 TUMPATI ANUJNA 15 443 1966147933 849 VOOSALA SANDESH 16 447 1966048173 849 GUNDREDDY SRAVANI 17 451 1966055455 848 T CHANDRA LEKHA 18 453 1966055035 848 DEEPAK GUPTA 19 464 1966039089 847 BHANU SRINIVAS YADLAPALLI 20 469 1966143769 846 KORLAKUNTA LAKSHMI BHARGAVI 21 492 1966047512 844 DESIRAJU YAJUSHI 22 496 1966038786 844 RM KEERTHANA 23 502 1966139362 843 DEVALLA -

The NEET PG Rank Wise List of Canidates Who Studied MBBS In

Dr. NTR UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES, VIJAYAWADA -8 As per the data received from the Ministry of Health , Government of India, the following is the NEET PG Rank wise list of canidates who studied MBBS in the State of Andhra Pradesh ( Based on the information provided by the candidates in the application form) and appeared for NEET PG 2020 conducted by NBE. Cut off Marks for Eligibility under General Category is 366 Marks, For PH category 342 Marks, for BC,SC,ST categories 319 Marks Note 1 : This is only for information of Students and Parents Note 2 : The final Merit position will be displayed only after submission of online application in response to the University Notification and after verification of original certificates/ eligibility as per rules NEET - S.No ROLL NO NAME OF THE CANDIDATE SCORE RANK 1 2066161932 CHAPPA PRAVALLIKA 938 41 2 2066015456 POTHIREDDY SHARANYA 931 56 3 2066090034 KOULALI SAI SAMARTH 931 61 4 2066153442 P SOWMYA 930 66 5 2066114879 PASUMARTHY SAI SRI HARSHA 926 79 6 2066056289 GUDIMETLA PRIYANKA 925 80 7 2066054521 ACHUTHA DATTATREYA 924 84 8 2066090718 SYED KHALEELULLAH 910 149 9 2066056746 DALLI SURESH 909 152 10 2066062929 TALASILA NAGA BHAVANI KRISHNA 903 190 11 2066090361 SANA ASFIYA 898 223 12 2066162715 NOUDURI VENKATA ABHISHEK 898 224 13 2066112146 N S L SUSMITHA 894 260 14 2066060592 SADHU KEERTHI 892 278 15 2066055410 CHEBOLU HARSHIKA 890 287 16 2066044484 BHAVANA CHANDA 888 314 17 2066062582 MANGALA THANMAYEE 887 319 18 2066044988 SHAIK MOHAMMAD KHASIM 887 325 19 2066056960 SAAHITI SUNKARA 885 -

December 2019 VOLUME No. 20 Sl.No. 12

Vol.20 No. 12 December - 2019 DR. B. SAROJA DEVI NATIONAL AWARD FOR 2019 Smt. Sumalatha, Member of Parliament receiving the Dr. B. Saroja Devi National Award 2019 on behalf of Shri. Ambareesh from Dr. C.N. Ashwath Narayana, Dy Chief Minister, Govt of Karnataka. Also seen Dr. B. Saroja Devi, Shri H.N. Suresh, Director, BVB, Shri. Abhishek son of Shri Ambareesh. The ceremony of the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Padmabhushana Dr. B. Saroja Bengaluru. Devi National award for 2019 It was an event that was was held on 17th November, punctuated with poignancy, as Sunday, at the Khincha Hall, Dr.B. Saroja Devi bestowed the 1 [email protected] Dr. C.N. Ashwath Narayan, Dy. Chief Minister, Govt of Karnataka being honoured by the dignitaries on the dais. Award posthumously on actor mentioned were recipients of the Ambareesh, who passed away award over the years. on November 24 last year. The programme included an The award was first given in introductory film on Ambareesh, 2010. Ambareesh had been an his life and contribution to active participant during previous cinema. It also included an award ceremonies since the time interview with Dr. Saroja Devi. it was instituted, and his absence was sorely missed. Shri. H.N. Suresh, Director, welcomed the gathering and The event saw a host of the distinguished guests. personalities from the Kannada He remembered how Ambareesh film world who attended the attended all the previous award programme out of respect for ceremonies, and that he had come the rebel star, as Ambareesh half an early for the programme was called. -

L45200mh1999plc118949 -11-Iepf-2

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form IEPF‐2 Date Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) CIN/BCIN L45200MH1999PLC118949 Prefill Company/Bank Name MAHINDRA LIFESPACE DEVELOPERS LIMITED 30‐JUL‐2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1913334.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id‐Client Id‐Account Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Number transferred (DD‐MON‐YYYY) NILESH N PUROHIT NATVARLAL PUROHIT 202 AMBA ASHISH 2ND FLOOR OPP AINDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400066 P40157581 Amount for unclaimed and un 6.00 03‐NOV‐2021 PETER M J M M JOSEPH C/O GLADWIN THOMAS PUTHENPAR INDIA KERALA COCHIN 682008 P40157697 Amount for unclaimed and un 60.00 03‐NOV‐2021 SWETHA SUNIL RAIKAR SUNIL PUSHPAVIHAR SOCIETY SHANTI NAGAINDIA MAHARASHTRA THANE 401102 P40158189 Amount for unclaimed and un 60.00 03‐NOV‐2021 CHANDRAKANT SHET XXXXXX LATE S GANAPATHISHET CHANDRA JEWELLERS CAR STREET MINDIA -

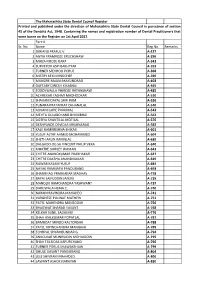

REGISTER PART-A.Xlsx

The Maharashtra State Dental Council Register Printed and published under the direction of Maharashtra State Dental Council in pursuance of section 45 of the Dentsits Act, 1948. Containing the names and registration number of Dental Practitioners that were borne on the Register on 1st April 2017. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 DIWANJI PRAFUL V. A-227 2 ANTIA FRAMROZE ERUCHSHAW A-296 3 MIRZA FIROZE DARA A-343 4 SURVEYOR ASPI BAKHTYAR A-352 5 TURNER MEHROO PORUS A-368 6 MISTRY KEKI MINOCHER A-396 7 MUNGRE RAJANI MAKUNDRAO A-403 8 DAFTARY DINESH KIKABHAI A-465 9 TODDYWALLA PHIROZE RATANSHAW A-485 10 ACHREKAR YASHMI MADHOOKAR A-510 11 SHAHANI DAYAL SHRI RAM A-526 12 TUNARA PRATAPRAY CHHANALAL A-540 13 ADVANI GOPE PARUMAL A-543 14 MEHTA GULABCHAND BHMJIBHAI A-562 15 DOTIYA SHANTILAL MOTILAL A-576 16 DESHPANDE DEVIDAS KRISHNARAO A-582 17 KALE RAMKRISHNA BHIKAJI A-601 18 YUSUF ALTAF AHMED MOHAMMED A-604 19 SHETH ARUN RAMNLAL A-639 20 DALGADO-DE-SA VINCENT PHILIP VERA A-640 21 MHATRE SHIRLEY WAMAN A-642 22 CHITRE ANANDKUMAR PRABHAKAR A-647 23 CHITRE DAKSHA ANANDKUMAR A-649 24 NAWAB KASAM YUSUF A-684 25 NAYAK RAMNATH PANDURANG A-693 26 SHANBHAG PRABHAKAR MADHAV A-718 27 BAPAI SAIFUDDIN JAFERJI A-729 28 MANDLIK RAMCHANDRA YASHWANT A-737 29 DARUWALA HEMA C. A-740 30 NARAIN RAVINDRA MAHADEO A-741 31 VARGHESE PULINAT MATHEW A-751 32 PATEL MAHENDRA MANSOOKH A-756 33 BHAGWAT SHARAD VASANT A-768 34 KELKAR SUNIL SADASHIV A-776 35 SHAH ANILKUMAR POPATLAL A-787 36 BAMBOAT MINOO RALTONSHA A-788 37 PATEL VIPINCHANDRA MANIBHAI A-789 38 ECHHPAL SHYAMSUNDAR G. -

The Development and Implementation of Tobacco-Free Movie Rules in India

THE DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF TOBACCO-FREE MOVIE RULES IN INDIA Amit Yadav, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 December 2020 THE DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF TOBACCO-FREE MOVIE RULES IN INDIA Amit Yadav, Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 December 2020 This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA-087472, the funding agency played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript. Opinions expressed reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the sponsoring agency. This report is available on the World Wide Web at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/75j1b2cg. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Indian film industry releases the largest number of movies in the world, 1500-2000 movies in Hindi and other regional languages, which are watched by more than 2 billion Indian moviegoers and millions more worldwide. • The tobacco industry has been using movies to promote their products for over a century. • In India, the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and Cable Television Networks Amendment Act, 1994, nominally provide for regulation of tobacco imagery in film and TV, but the Ministry of Information and Broadcast (MoIB), the nodal ministry, has not considered tobacco imagery. • The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act, 2003 (COPTA), enforced by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), prohibited direct and indirect advertisement of tobacco products. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 03.01.2016 to 09.01.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 03.01.2016 to 09.01.2016 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PUTHUVAL,NEERK KUNNAM,AMBALA Cr. 15/16, u/s V.P.DILEEP 1 POLICE BAIL ANEESH PPUZHA NORTH AMBALAPPU 3.1.16 279 IPC & AMBALAPU KUMAR, S I KUMAR BABU 36 M P/W-16 ZHA 13.15 185,188 Act ZHA of POLICE THURUTHIL 2 CHIRA,THENNADY Cr. 16/16, u/s V.P.DILEEP POLICE BAIL JAIME JOHN ,CHIRAYAKOM P 3.1.16 279 IPC & AMBALAPU KUMAR, S I JOHN JOSEPH 35 M O,THAKAZHI PW-4 THAKAZHI 17.35 185,188 Act ZHA of POLICE KURISUM MOOLA VEEDU,VIRIPPALA Cr. 17/16, u/s V.P.DILEEP 3 POLICE BAIL VARKKI MURI,THAKAZHI P 3.1.16 279 IPC & AMBALAPU KUMAR, S I JOHN YOHANNAN 40 M W-6 THAKAZHY 19.40 185,188 Act ZHA of POLICE PUTHUVAL CHEMPAZHANTHY ,MADHAVA Cr. 18/16, U/S 4 POLICE BAIL MUKKU,AMBALAP 279 IPC & V.P.DILEEP PUZHA NORTH IRATTAKKUL 3.1.16 185 of M V AMBALAPU KUMAR, S I BIJU ANANDAN 42 M P/W-17 ANGARA 19.45 Act ZHA of POLICE PUTHUVAL,KOMA NA Cr. 20/16, u/s V.P.DILEEP 5 POLICE BAIL ,AMBALAPPUZHA 3.1.16 15(C) R/W 63 AMBALAPU KUMAR, S I BAIJU VIJAYAN 41 M SOUTH P/W-15 KOMANA 22.15 of K A Act ZHA of POLICE KIZHAKKEPAMAN PADA,ARAVUKAD Cr.