EZH2 in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interplay Between Epigenetics and Metabolism in Oncogenesis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches

OPEN Oncogene (2017) 36, 3359–3374 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Interplay between epigenetics and metabolism in oncogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches CC Wong1, Y Qian2,3 and J Yu1 Epigenetic and metabolic alterations in cancer cells are highly intertwined. Oncogene-driven metabolic rewiring modifies the epigenetic landscape via modulating the activities of DNA and histone modification enzymes at the metabolite level. Conversely, epigenetic mechanisms regulate the expression of metabolic genes, thereby altering the metabolome. Epigenetic-metabolomic interplay has a critical role in tumourigenesis by coordinately sustaining cell proliferation, metastasis and pluripotency. Understanding the link between epigenetics and metabolism could unravel novel molecular targets, whose intervention may lead to improvements in cancer treatment. In this review, we summarized the recent discoveries linking epigenetics and metabolism and their underlying roles in tumorigenesis; and highlighted the promising molecular targets, with an update on the development of small molecule or biologic inhibitors against these abnormalities in cancer. Oncogene (2017) 36, 3359–3374; doi:10.1038/onc.2016.485; published online 16 January 2017 INTRODUCTION metabolic genes have also been identified as driver genes It has been appreciated since the early days of cancer research mutated in some cancers, such as isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 16 17 that the metabolic profiles of tumor cells differ significantly from and 2 (IDH1/2) in gliomas and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 18 normal cells. Cancer cells have high metabolic demands and they succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in paragangliomas and fuma- utilize nutrients with an altered metabolic program to support rate hydratase (FH) in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell 19 their high proliferative rates and adapt to the hostile tumor cancer (HLRCC). -

REVIEW Chromatin Modifications and DNA Double-Strand Breaks

Leukemia (2007) 21, 195–200 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0887-6924/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/leu REVIEW Chromatin modifications and DNA double-strand breaks: the current state of play TC Karagiannis1,2 and A El-Osta3 1Molecular Radiation Biology, Trescowthick Research Laboratories, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; 2Department of Pathology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and 3Epigenetics in Human Health and Disease, Baker Medical Research Institute, The Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct, Prahran, Victoria, Australia The packaging and compaction of DNA into chromatin is mutated (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia-related (also known as important for all DNA-metabolism processes such as transcrip- Rad3-related, ATR), which are members of the phosphoinositide tion, replication and repair. The involvement of chromatin 4,5 modifications in transcriptional regulation is relatively well 3-kinase (PI(3)K) superfamily. They catalyse the phosphoryla- characterized, and the distinct patterns of chromatin transitions tion of numerous downstream substrates that are involved in 4,5 that guide the process are thought to be the result of a code on cell-cycle regulation, DNA repair and apoptosis. the histone proteins (histone code). In contrast to transcription, In mammalian cells, DSBs are repaired by one of two distinct the intricate link between chromatin and responses to DNA and complementary pathways – homologous recombination damage has been given attention only recently. It is now (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ).6,7 Briefly, NHEJ emerging that specific ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling involves processing of the broken DNA terminii to make them complexes (including the Ino80, Swi/Snf and RSC remodelers) 3 and certain constitutive (methylation of lysine 79 of histone H3) compatible, followed by a ligation step. -

Annotated Classic Histone Code and Transcription

Annotated Classic Histone Code and Transcription Jerry L. Workman1,* 1Stowers Institute for Medical Research, 1000 East 50th Street, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] We are pleased to present a series of Annotated Classics celebrating 40 years of exciting biology in the pages of Cell. This install- ment revisits “Tetrahymena Histone Acetyltransferase A: A Homolog to Yeast Gcn5p Linking Histone Acetylation to Gene Activa- tion” by C. David Allis and colleagues. Here, Jerry Workman comments on how the discovery of Tetrahymena histone acetyltrans- ferase A, a homolog to a yeast transcriptional adaptor Gcn5p, by Allis led to the establishment of links between histone acetylation and gene activation. Each Annotated Classic offers a personal perspective on a groundbreaking Cell paper from a leader in the field with notes on what stood out at the time of first reading and retrospective comments regarding the longer term influence of the work. To see Jerry L. Workman’s thoughts on different parts of the manuscript, just download the PDF and then hover over or double- click the highlighted text and comment boxes on the following pages. You can also view Workman’s annotation by opening the Comments navigation panel in Acrobat. Cell 158, August 14, 2014, 2014 ©2014 Elsevier Inc. Cell, Vol. 84, 843±851, March 22, 1996, Copyright 1996 by Cell Press Tetrahymena Histone Acetyltransferase A: A Homolog to Yeast Gcn5p Linking Histone Acetylation to Gene Activation James E. Brownell,* Jianxin Zhou,* Tamara Ranalli,* 1995; Edmondson et al., submitted). Thus, the regulation Ryuji Kobayashi,² Diane G. Edmondson,³ of histone acetylation is an attractive control point for Sharon Y. -

Histone Methylases As Novel Drug Targets. Focus on EZH2 Inhibition. Catherine BAUGE1,2,#, Céline BAZILLE 1,2,3, Nicolas GIRARD1

Histone methylases as novel drug targets. Focus on EZH2 inhibition. Catherine BAUGE1,2,#, Céline BAZILLE1,2,3, Nicolas GIRARD1,2, Eva LHUISSIER1,2, Karim BOUMEDIENE1,2 1 Normandie Univ, France 2 UNICAEN, EA4652 MILPAT, Caen, France 3 Service d’Anatomie Pathologique, CHU, Caen, France # Correspondence and copy request: Catherine Baugé, [email protected], EA4652 MILPAT, UFR de médecine, Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, CS14032 Caen cedex 5, France; tel: +33 231068218; fax: +33 231068224 1 ABSTRACT Posttranslational modifications of histones (so-called epigenetic modifications) play a major role in transcriptional control and normal development, and are tightly regulated. Disruption of their control is a frequent event in disease. Particularly, the methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27), induced by the methylase Enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), emerges as a key control of gene expression, and a major regulator of cell physiology. The identification of driver mutations in EZH2 has already led to new prognostic and therapeutic advances, and new classes of potent and specific inhibitors for EZH2 show promising results in preclinical trials. This review examines roles of histone lysine methylases and demetylases in cells, and focuses on the recent knowledge and developments about EZH2. Key-terms: epigenetic, histone methylation, EZH2, cancerology, tumors, apoptosis, cell death, inhibitor, stem cells, H3K27 2 Histone modifications and histone code Epigenetic has been defined as inheritable changes in gene expression that occur without a change in DNA sequence. Key components of epigenetic processes are DNA methylation, histone modifications and variants, non-histone chromatin proteins, small interfering RNA (siRNA) and micro RNA (miRNA). -

Histone Crosstalk Between H3s10ph and H4k16ac Generates a Histone Code That Mediates Transcription Elongation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Histone Crosstalk between H3S10ph and H4K16ac Generates a Histone Code that Mediates Transcription Elongation Alessio Zippo,1 Riccardo Serafini,1 Marina Rocchigiani,1 Susanna Pennacchini,1 Anna Krepelova,1 and Salvatore Oliviero1,* 1Dipartimento di Biologia Molecolare Universita` di Siena, Via Fiorentina 1, 53100 Siena, Italy *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.031 SUMMARY which generates a different binding platform for the further recruitment of proteins that regulate gene expression. The phosphorylation of the serine 10 at histone H3 In Drosophila it has been shown that H3S10ph is required for has been shown to be important for transcriptional the recruitment of the positive transcription elongation factor activation. Here, we report the molecular mechanism b (P-TEFb) on the heat shock genes (Ivaldi et al., 2007) although through which H3S10ph triggers transcript elonga- these results have been challenged (Cai et al., 2008). tion of the FOSL1 gene. Serum stimulation induces In mammalian cells, nucleosome phosphorylation localized at the PIM1 kinase to phosphorylate the preacetylated promoters has been directly linked with transcriptional activa- tion. It has been shown that H3S10ph enhances the recruitment histone H3 at the FOSL1 enhancer. The adaptor of GCN5, which acetylates K14 on the same histone tail (Agalioti protein 14-3-3 binds the phosphorylated nucleo- et al., 2002; Cheung et al., 2000). Steroid hormone induces the some and recruits the histone acetyltransferase transcriptional activation of the MMLTV promoter by activating MOF, which triggers the acetylation of histone H4 MSK1 that phosphorylates H3S10, leading to HP1g displace- at lysine 16 (H4K16ac). -

Non-Coding Rnas As Regulators in Epigenetics (Review)

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 37: 3-9, 2017 Non-coding RNAs as regulators in epigenetics (Review) JIAN-WEI WEI*, KAI HUANG*, CHAO YANG* and CHUN-SHENG KANG Department of Neurosurgery, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Laboratory of Neuro-Oncology, Tianjin Neurological Institute, Key Laboratory of Post-trauma Neuro-repair and Regeneration in the Central Nervous System, Ministry of Education, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Injuries, Variations and Regeneration of the Nervous System, Tianjin 300052, P.R. China Received June 12, 2016; Accepted November 2, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/or.2016.5236 Abstract. Epigenetics is a discipline that studies heritable Contents changes in gene expression that do not involve altering the DNA sequence. Over the past decade, researchers have 1. Introduction shown that epigenetic regulation plays a momentous role 2. siRNA in cell growth, differentiation, autoimmune diseases, and 3. miRNA cancer. The main epigenetic mechanisms include the well- 4. piRNA understood phenomenon of DNA methylation, histone 5. lncRNA modifications, and regulation by non-coding RNAs, a mode 6. Conclusion and prospective of regulation that has only been identified relatively recently and is an area of intensive ongoing investigation. It is gener- ally known that the majority of human transcripts are not 1. Introduction translated but a large number of them nonetheless serve vital functions. Non-coding RNAs are a cluster of RNAs Epigenetics is the study of inherited changes in pheno- that do not encode functional proteins and were originally type (appearance) or gene expression that are caused by considered to merely regulate gene expression at the post- mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA transcriptional level. -

A Phosphorylated Subpopulation of the Histone Variant Macroh2a1 Is Excluded from the Inactive X Chromosome and Enriched During Mitosis

A phosphorylated subpopulation of the histone variant macroH2A1 is excluded from the inactive X chromosome and enriched during mitosis Emily Bernstein*†, Tara L. Muratore-Schroeder‡, Robert L. Diaz*§, Jennifer C. Chow¶, Lakshmi N. Changolkarʈ, Jeffrey Shabanowitz‡, Edith Heard¶, John R. Pehrsonʈ, Donald F. Hunt‡**, and C. David Allis*†† *Laboratory of Chromatin Biology, The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065; Departments of ‡Chemistry and **Pathology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22901; ¶Curie Institute, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 218, 26 Rue d’Ulm, 75005 Paris, France; and ʈDepartment of Animal Biology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Contributed by C. David Allis, December 11, 2007 (sent for review November 26, 2007) Histone variants play an important role in numerous biological (5). Importantly, and unlike most other well studied variants, processes through changes in nucleosome structure and stability mH2A is vertebrate-specific, consistent with the general view and possibly through mechanisms influenced by posttranslational that evolutionary expansion may correlate with increased needs modifications unique to a histone variant. The family of histone for functional specialization (6). Three isoforms exist in mam- H2A variants includes members such as H2A.Z, the DNA damage- mals: mH2A1.1, mH2A1.2, and mH2A2. The former two are associated H2A.X, macroH2A (mH2A), and H2ABbd (Barr body- alternatively spliced from the mH2A1 gene and differ only by deficient). Here, we have undertaken the challenge to decipher the one exon in the macro domain, whereas a second gene encodes posttranslational modification-mediated ‘‘histone code’’ of mH2A, mH2A2 (6, 7). -

Replication-Coupled Chromatin Remodeling: an Overview of Disassembly and Assembly of Chromatin During Replication

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Replication-Coupled Chromatin Remodeling: An Overview of Disassembly and Assembly of Chromatin during Replication Céline Duc and Christophe Thiriet * UFIP UMR-CNRS 6286, Épigénétique et Dynamique de la Chromatine, Université de Nantes, 2 rue de la Houssinière, 44322 Nantes, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The doubling of genomic DNA during the S-phase of the cell cycle involves the global remodeling of chromatin at replication forks. The present review focuses on the eviction of nucle- osomes in front of the replication forks to facilitate the passage of replication machinery and the mechanism of replication-coupled chromatin assembly behind the replication forks. The recycling of parental histones as well as the nuclear import and the assembly of newly synthesized histones are also discussed with regard to the epigenetic inheritance. Keywords: replication; chromatin; histones 1. Introduction The doubling of genomic DNA occurring in the S-phase involves a timely regulated remodeling of the entire chromatin. Indeed, each replication site requires the displacement of nucleosomes in front of the fork to enable the progression of the replication machinery Citation: Duc, C.; Thiriet, C. and the reformation of chromatin behind the replication fork [1,2]. The mechanism of Replication-Coupled Chromatin histone eviction to facilitate the progression of the replication and replication-coupled Remodeling: An Overview of chromatin assembly with parental and newly synthesized histones is conserved through Disassembly and Assembly of the entire eukaryotic kingdom [2]. The histones are the most abundant proteins in the Chromatin during Replication. Int. -

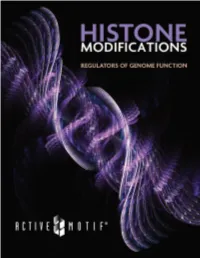

Histone Modifications

The Histone Code Domain Modification Proteins The “histone code” hypothesis put forward in 2000* suggests that specific 14-3-3 H3 Ser10 Phos, Ser28 Phos 14-3-3 Family histone modifications or combinations Ank H3 Lys9 Methyl GLP of modifications confer unique biological functions to the regions of the genome BIR H3 Thr3 Phos Survivin associated with them, and that special- BRCT H2AX Ser139 Phos 53BP1, BRCA1, MDC1, ized binding proteins (readers) facilitate NBS1 the specialized function conferred by the histone modification. Evidence is accumu- Bromo H3 Lys9 Acetyl BRD4, BAZ1B lating that these histone modification / H3 Lys14 Acetyl BRD4, BAZ1B, BRG1 binding protein interactions give rise to H4 Lys5 Acetyl BRD4 downstream protein recruitment, poten- H4 Lys12 Acetyl BRD2, BRD4 tially facilitating enzyme and substrate interactions or the formation of unique Chromo H3 Lys4 Methyl CHD1 chromatin domains. Specific histone H3 Lys9 Methyl CDY, HP1, MPP8, modification-binding domains have been H3 Lys27 Methyl CDY, Pc identified, including the Tudor, Chromo, H3 Lys36 Methyl MRG15 Bromo, MBT, BRCT and PHD motifs. MBT H3 Lys9 Methyl L3MBTL1, L3MBTL2 H4 Lys20 Methyl L3MBTL1, MBTD1 PID H2AX Tyr142 Phos APBB1 PHD H3 Lys4 Methyl BPTF, ING, RAG2, BHC80, DNMT3L, PYGO1, JMJD2A H3 Lys9 Methyl UHRF H4 Lys20 Methyl JMJD2A, PHF20 TDR H3 Lys9 Methyl TDRD7 H3 Arg17 Methyl TDRD3 H4 Lys20 Methyl 53BP1 WD H3 Lys4 Methyl WDR5 FIGURE H3 Lys9 Methyl EED Resetting Histone Methylation. Crystal structure** of the catalytic domain of the histone demethy- lase JMJD2A bound to a peptide derived from the amino terminus of histone H3, trimethylated at * Strahl BD, Allis CD (2000). -

Histone Onco-Modifications

Oncogene (2011) 30, 3391–3403 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/11 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Histone onco-modifications JFu¨llgrabe, E Kavanagh and B Joseph Department of Oncology-Pathology, Cancer Centrum Karolinska, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Post-translational modification of histones provides an (Luger et al., 1997). In eukaryotes, an octamer of important regulatory platform for processes such as gene histones-2 copies of each of the four core histone expression, DNA replication and repair, chromosome proteins histone 2A (H2A), histone 2B (H2B), histone condensation and segregation and apoptosis. Disruption of 3 (H3) and H4—is wrapped by 147 bp of DNA to form these processes has been linked to the multistep process of a nucleosome, the fundamental unit of chromatin carcinogenesis. We review the aberrant covalent histone (Kornberg and Lorch, 1999). Nucleosomal arrays were modifications observed in cancer, and discuss how these observed with electron microscopy as a series of ‘beads epigenetic changes, caused by alterations in histone- on a string’, the ‘beads’ being the individual nucleo- modifying enzymes, can contribute to the development of somes and the ‘string’ being the linker DNA. Linker a variety of human cancers. As a conclusion, a new histones, such as histone H1, and other non-histone terminology ‘histone onco-modifications’ is proposed to proteins can interact with the nucleosomal arrays to describe post-translational modifications of histones, further package the nucleosomes to form higher-order which have been linked to cancer. This new term would chromatin structures (Figure 1a). take into account the active contribution and importance Histones are no longer considered to be simple ‘DNA- of these histone modifications in the development and packaging’ proteins; they are recognized as being progression of cancer. -

Chromatin Structure and DNA Double-Strand Break Responses in Cancer Progression and Therapy

Oncogene (2007) 26, 7765–7772 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Chromatin structure and DNA double-strand break responses in cancer progression and therapy JA Downs MRC Genome Damage and Stability Centre, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, UK Defects in the detection and repair of DNA double-strand recentwork proposes thatchromosomal instabilityis breaks (DSBs) have been causatively linked to tumourigen- likely to be a driving force in the process of tumourigen- esis. Moreover, inhibition of DNA damage responses esis (Michor, 2005). This suggests that the ability of cells (DDR) can increase the efficacy of cancer therapies that to detect and, appropriately and efficiently, respond to rely on generation of damaged DNA. DDR must occur DNA lesions is critical in preventing the onset of within the context of chromatin, and there have been tumourigenesis. significant advances in recent years in understanding how One of the most dangerous DNA lesions a cell can the modulation and manipulation of chromatin contribute sustain is a DNA double-strand break (DSB). If left to this activity. One particular covalent modification of a unrepaired, a single DSB can be lethal, and can also histone variant—the phosphorylation of H2AX—has been result in chromosomal translocations, deletions and loss investigated in great detail and has been shown to have of genetic information. In eukaryotes, there are two important roles in DNA DSB responses and in preventing main pathways for repairing DSBs; homologous re- tumourigenesis. These studies are reviewed here in the combination (HR) and nonhomologous end joining. -

Translating the Histone Code Thomas Jenuwein1 and C

E PIGENETICS 69. Y. Habu, T. Kakutani, J. Paszkowski, Curr. Opin. Genet. 79. C. Cogoni et al., EMBO J. 15, 3153 (1996). 89. P. SanMiguel et al., Science 274, 765 (1996). Dev. 11, 215 (2001). 80. G. Faugeron, Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3, 144 (2000). 90. R. Mauricio, Nature Rev. Genet. 2, 370 (2001). 70. M. Wassenegger, Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 203 (2000). 81. L. Jackson-Grusby et al., Nature Genet. 27, 31 (2001). 91. P. Cubas, C. Vincent, E. Coen, Nature 401, 157 (1999). 71. M. A. Matzke, A. J. Matzke, J. M. Kooter, Science 293, 82. J. P. Vielle-Calzada, R. Baskar, U. Grossniklaus, Nature 92. R. Martienssen, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 240 1080 (2001). 404, 91 (2000). (1998). 72. J. Bender, Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 252 (1998). Genes Dev. 11 73. E. U. Selker, Cell 97, 157 (1999). 83. P. S. Springer, D. R. Holding, A. Groover, C. Yordan, 93. Z. J. Chen, C. S. Pikaard, , 2124 (1997). 74. M. N. Raizada, M. I. Benito, V. Walbot, Plant J. 25,79 R. A. Martienssen, Development 127, 1815 (2000). 94. L. Comai et al., Plant Cell 12, 1551 (2000). (2001). 84. J. P. Vielle-Calzada et al., Genes Dev. 13, 2971 (1999). 95. H. S. Lee, Z. J. Chen, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 75. R. F. Ketting, T. H. Haverkamp, H. G. van Luenen, R. H. 85. R. Vinkenoog et al., Plant Cell 12, 2271 (2000). 6753 (2001). Plasterk, Cell 99, 133 (1999). 86. S. Adams, R. Vinkenoog, M. Spielman, H. G. Dickinson, 96.