Broadcasting Its New Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera NMAH.AC.1211 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2019 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Stage Musicals and Vaudeville, 1866-2007, undated............................... 4 Series 2: Motion Pictures, 1912-2007, undated................................................... 327 Series 3: Television, 1933-2003, undated............................................................ 783 Series 4: Big Bands and Radio, 1925-1998, -

Web Paramount Historical Calendar 6-12-2016.Xlsx

Paramount Historical Calendar Last Update 612-2016 Paramount Historical Calendar 1928 - Present Performance Genre Event Title Performance Performan Start Date ce End Date Instrumental - Group Selections from Faust 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie Memories 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie News of the Day 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Instrumental - Group Organs We Have Played 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Musical Play A Merry Widow Revue 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Dance Accent & Jenesko 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Dance Felicia Sorel Girls 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Vocal - Group The Royal Quartette 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Comedian Over the Laughter Hurdles 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Vocal - Group The Merry Widow Ensemble 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie Feel My Pulse 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/1/1928 3/7/1928 Movie The Big City 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Variety Highlights 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian A Comedy Highlight 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Vocal - Individual An Operatic Highllight 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Variety Novelty (The Living Marionette) 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Syncopated 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Slow Motion 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Dance Millitary Gun Drill 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian Traffic 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Instrumental - Group novelty arrangement 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Comedian Highlights 3/8/1928 3/14/1928 Movie West Point 3/15/1928 3/21/1928 Instrumental - Individual Don & Ron at the grand organ 3/15/1928 3/21/1928 Variety -

Titolo Anno Imdb ...All the Marbles 01/01/1981 10,000 Bc

TITOLO ANNO IMDB ...ALL THE MARBLES 01/01/1981 10,000 BC 01/01/2008 11TH HOUR 01/03/2008 15 MINUTES 01/01/2001 20,000 YEARS IN SING SING 01/01/1933 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY 01/01/1968 2010 01/01/1984 3 MEN IN WHITE 01/01/1944 300 01/06/2007 300: RISE OF AN EMPIRE 01/05/2014 36 HOURS 01/01/1965 42 01/07/2013 42ND STREET 01/01/1933 50 MILLION FRENCHMEN 01/01/1931 6 DAY BIKE RIDER 01/01/1934 6,000 ENEMIES 01/01/1939 7 FACES OF DR. LAO 01/01/1964 7 WOMEN 01/01/1966 8 SECONDS 01/01/1994 A BIG HAND FOR THE LITTLE LADY 01/01/1966 A CERTAIN YOUNG MAN 01/01/1928 A CHILD IS BORN 01/01/1940 A CHRISTMAS CAROL 01/01/1938 A CHRISTMAS STORY 01/01/1983 A CINDERELLA STORY 01/02/2005 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE 01/01/2013 A COVENANT WITH DEATH 01/01/1967 A DATE WITH JUDY 01/01/1948 A DAY AT THE RACES 01/01/1937 A DISPATCH FROM REUTER'S 01/01/1940 A DISTANT TRUMPET 01/01/1964 A DOLPHIN TALE 01/03/2012 A DREAM OF KINGS 01/01/1970 A FACE IN THE CROWD 01/01/1957 A FAMILY AFFAIR 01/01/1937 A FAN'S NOTES 01/01/1972 A FEVER IN THE BLOOD 01/01/1961 A FINE MADNESS 01/01/1966 A FREE SOUL 01/01/1931 A FUGITIVE FROM JUSTICE 01/01/1940 A GLOBAL AFFAIR 01/01/1964 A GUY NAMED JOE 01/01/1943 A KISS IN THE DARK 01/01/1949 A LA SOMBRA DEL PUENTE 01/01/1948 A LADY OF CHANCE 01/01/1928 A LADY WITHOUT PASSPORT 01/01/1950 A LADY'S MORALS 01/01/1930 A LETTER FOR EVIE 01/01/1946 A LIFE OF HER OWN 01/01/1950 A LION IS IN THE STREETS 01/01/1953 A LITTLE JOURNEY 01/01/1927 A LITTLE PRINCESS 01/01/1995 A LITTLE ROMANCE 01/01/1979 A LOST LADY 01/01/1934 A MAJORITY OF ONE 01/01/1962 A MAN AND -

Polk, Ducktown, Copperhill Try to Save Hospital from IRS, Debt

SPORTS: LOCAL NEWS: Bosken resigns Memorial Day as Raider wrestling poppies available coach: Page 13 Saturday: Page 12 163rd Year • No. 23 24 paGes • 50¢ CLEVELAND, TN 37311 THE CITY WITH SPIRIT FRIDAY, MAY 26, 2017 Resolute looks Polk, Ducktown, to future in face Copperhill try of less demand to save hospital for newsprint from IRS, debt By BRIAN GRAVES [email protected] The president of Resolute Forest Products said Thursday his company is secure in its investments Commissioners vote to buy for the future at the company’s Calhoun plant. Richard Garneau was in attendance as the com- the remainder of bank loan pany hosted its stockholders at the Museum Center at Five Points. By LARRY C. BOWERS the bank loan and facing The Calhoun location is one of the earliest [email protected] default and foreclosure. newsprint mills in the South. Polk County Executive Hoyt Polk County and the city of In 2015, Resolute began con- Firestone and county attorney Ducktown are taking steps to struction of a $270 million state- Eric Brooks have been talking keep the Copper Basin of-the-art tissue machine and with bank officials concerning Hospital District afloat, at least converting operation in Calhoun the situation. To deflect fore- for the immediate future. to manufacture retail, premium closure proceedings, an option The hospital is wallowing in private-label tissue products. is to purchase the remainder of a quagmire of debt, especially “It’s probably going to take a the loan, becoming the lender on a $1.4 million bank loan year or two to bring production to of the hospital funds. -

List of 7200 Lost US Silent Feature Films 1912-29

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 12/29/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – approximately 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) -

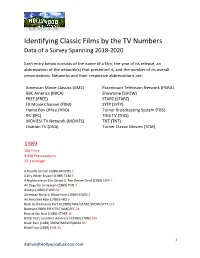

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

And Welcome to It 2 X 3.5" Ad

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? May 26 - June 1, 2017 Jennifer Lopez is a judge on “World of 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad Dance,” premiering We’ve got you covered! Tuesday on NBC. waxahachietx.com V E I N T R I G U E R T V O L 2 x 3" ad A R O S A S O O C A P U L E T Your Key H C A P L U I S B E V L I O P To Buying E R I V A L R Y A F J A H V I E B W O O I R I V L H F A E B and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad B T E V T E L Y N T I T K R T R R N E A M S C A X K N G O W I E I R G A R M L E Y P E N E B A V G U N R B O S A L J A Z B C L Y G E R E T C L Y N C H S H Q X T S W N E A M I Q U E V E U F C R B O W L E R W H V B R A V E N A D H U R Z S E T O Y R C G U D Y N S A E F A M U S M O N T A G U E V Y N D E “Still Star-Crossed” on ABC (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Benvolio (Montague) (Wade) Briggs Aftermath Place your classified Solution on page 13 Rosaline (Capulet) (Lashana) Lynch Verona ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad (Prince) Escalus (Sterling) Sulieman Treachery Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and (Lord) Montague (Grant) Bowler (Palace) Intrigue Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lord) Capulet (Anthony) Head Rivalry Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it It’s a ‘World of Dance’ and welcome to it 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light SUNDAY sportszone 11:00 a.m.