The Incremental Development Scheme a Case Study of Khuda-Ki-Basti In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

December 2013 405 Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd

Appendix IV Scheduled Banks’ Islamic Banking Branches in Pakistan As on 31st December 2013 Al Baraka Bank -Lakhani Centre, I.I.Chundrigar Road Vehari -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, D.H.A. (Pakistan) Ltd. (108) -Phase-II, D.H.A. -Provincial Trade Centre, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Askari Bank Ltd. (38) Main University Road Abbottabad -S.I.T.E. Area, Abbottabad Arifwala Chillas Attock Khanewal Faisalabad Badin Gujranwala Bahawalnagar Lahore (16) Hyderabad Bahawalpur -Bank Square Market, Model Town Islamabad Burewala -Block Y, Phase-III, L.C.C.H.S Taxila D.G.Khan -M.M. Alam Road, Gulberg-III, D.I.Khan -Main Boulevard, Allama Iqbal Town Gujrat (2) Daska -Mcleod Road -Opposite UBL, Bhimber Road Fateh Jang -Phase-II, Commercial Area, D.H.A. -Near Municipal Model School, Circular Gojra -Race Course Road, Shadman, Road Jehlum -Block R-1, Johar Town Karachi (8) Kasur -Cavalry Ground -Abdullah Haroon Road Khanpur -Circular Road -Qazi Usman Road, near Lal Masjid Kotri -Civic Centre, Barkat Market, New -Block-L, North Nazimabad Minngora Garden Town -Estate Avenue, S.I.T.E. Okara -Faisal Town -Jami Commercial, Phase-VII Sheikhupura -Hali Road, Gulberg-II -Mehran Hights, KDA Scheme-V -Kabeer Street, Urdu Bazar -CP & Barar Cooperative Housing Faisalabad (2) -Phase-III, D.H.A. Society, Dhoraji -Chiniot Bazar, near Clock Tower -Shadman Colony 1, -KDA Scheme No. 24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal -Faisal Lane, Civil Line Larkana Kohat Jhang Mansehra Lahore (7) Mardan -Faisal Town, Peco Road Gujranwala (2) Mirpur (AK) -M.A. Johar Town, -Anwar Industrial Complex, G.T Road Mirpurkhas -Block Y, Phase-III, D.H.A. -

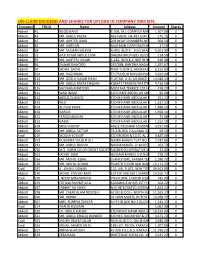

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

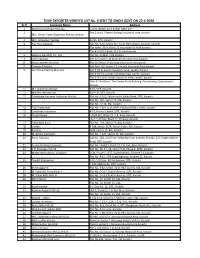

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT to SINDH GOVT on 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND

TDAP EXPORTER VERIFIED LIST No. 9 SENT TO SINDH GOVT ON 22-4-2020 Sr.# Company Name Address 1 Multinational Export Bureau L-10 D, BLOCK 22, F B IND. AREA KHI 2 Plot 2 and 17 Sector Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi M/s. United Towel Exporters Private Limited 3 M/s. Homecare Textiles D-115, SITE, Karachi 4 Five Star Apparels Plot No. E-92, Sector No. 31-D, P&T Society, Korangi, Karachi. Plot No# L-33/A, Block 22 Industrial F.B Area Karachi Plot # LA 8/19 Block 22 F.B Area Karachi 5 Lakhany Silk Mills Pvt. Ltd. Plot No. D/48-D, SITE Karachi 7 Vista Apparels Plot 6/1, Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 8 Nova Leathers (Pvt) Ltd Plot 30 Sector 15 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 9 Threads & Motifs Plot No# 126, Sector 15, Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 10 Gul Ahmed Textile Mills Ltd Plot # HT-8, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # HT-19, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi Plot # H-5, H-6, Landhi Industrial Area, Landhi, Karachi 16th & 23rd Floor, The Center Point Building, Expressway, Qayyumabad, Karachi 11 M.I. Industries (Dying) B-45, SITE, Karachi. 12 Mahee International F/413-B, SITE, Karachi. 13 Cambridge Garment Industries Pvt Ltd. Plot No. A-5/1, Fakharuddin Valika Road, SITE, Karachi. Plot No. 102, Sector 27, KIA, Karachi. Plot No. C-124, KIA, Karachi. 14 ZIQI Enterprises Plot No. 2 & 9, A-VI, KEPZ, PO Box18700, Landhi, Karachi. 15 Combined Industries A-15, Binoria Chowk, SITE, Karachi. 16 Globe Dyeing L-26/B & C, Block 22, F.B. -

Orangi Pilot Project Programs

822 PK0R92 ORANGI PILOT PROJECT PROGRAMS AKHTER HAMEED KHAN SECOND ADOlTiON. DEC-1992 OPP - RTI ORANGI PILOT PROJECT - RESEARCH & TRAINING INSTITUTE ST-4. SECTOR 5/A, QASBA TOWN SHIP, MANGHOPIR ROAD , KARACHI. Tel: 8652297-6658021 CONTENTS Section 1 - ORANGI PILOT PROJECT 1-4 Section 2 - OPP'S LOW COST SANITATION PROGRAM 5-13 Section 3 - LOW COST HOUSE BUILDING PROGRAM 14-20 Section 4 - HEALTH AND FAMILY PLANNING PROGRAM FOR LOW INCOME HOUSEWIVES 21 - 26 Section 5 - PROGRAM OF WOMEN WORK CENTRES 27-33 Section 6 - ECONOMIC PROGRAM FOR FAMILY ENTERPRISE UNITS 34-42 Section 7 - ORANGI SCHOOLS - EDUCATION PROJECT 43 - 52 OPP PUBLICATION ORANGI MAP SECTION 1 -ORANGI PILOT PROJECT l.Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) OPP was sponsored by BCCI Foundation.lt has been working in Orangi since April 1980.It publishes a quarterly progress report which contains financial statements and quarterly and cumulative tables of work.The 45th report has come out in April 1991.Besides numerous case studies and monographs have also been published. OPP considers itself a research institution whose objective is to analyse outstanding problems of Orangi,and then, through prolonged action research and extension education, discover viable solutions.OPP itself does not construct sewerage lines,or set up clinics or schools or industrial homes etc.It only promotes community organisation and self management.By providing social and technical guidance it en- courages the mobilisation of local managerial and financial resources, and the practice of cooperative action. OPP is very fortunate,thanks to BCCI Foundation and other donors,in possessing both the resources and the autonomy required for innovative research,experiments, demonstration, and extension. -

THE BANK of KHYBER LIST of BRANCHES PROVIDING CLEARING FACILITY THROUGH NIFT Bank Branch Branch Name Address City Code Code Shop No

THE BANK OF KHYBER LIST OF BRANCHES PROVIDING CLEARING FACILITY THROUGH NIFT Bank Branch Branch Name Address City Code Code Shop No. 1 to 6 (Ground Floor) and Office No. 1 to 3 (First Floor), Olympic Plaza, Qayyum Stadium, Bara 061 0001 Peshawar, Main Corporate Branch Road, Peshawar Cantt. PESHAWAR 061 0002 Peshawar, University Road Ghaffar Plaza, Adjacent to Sheraz Restaurant, University Road, Peshawar PESHAWAR 061 0003 Kohat, Bannu Road Cantonment Plaza Bannu Road, Kohat PESHAWAR 061 0004 D. I. Khan Circular Road Circular Road, D.I.Khan D.I.KHAN 061 0007 Mardan, Chamber House Grund floor, Chamber House, Aiwan-e-Sanat-o-Tijarat Road, Collage Chowk, Mardan. PESHAWAR 061 0010 Peshawar, G. T. Road Ground floor, Afandi Tower, Bilal Town, G.T. Road, Peshawar PESHAWAR 061 0013 Peshawar, Saddar Road Shop No.9,10 & 11, at Super Market, Adjacent State Bank of Pakistan Peshawar, Saddar Road, Peshawar PESHAWAR 061 0014 Hattar Branch Industrial Estate Hattar, Haripur ABBOTTABAD 061 0015 Peshawar, Civil Secretariat Civil Secretariat , Peshawar PESHAWAR 061 0016 Peshawar, Khyber Bazar Abbasin Hotel, Khyber Bazar, Peshawar PESHAWAR 061 0019 Haripur Branch Shahrah-e-Hazara, Haripur. ABBOTTABAD 061 0022 Islamabad, Blue area Zahoor Plaza, Blue Area, Islamabad. ISLAMABAD 061 0023 Lahore, M.M. Alam Road Gulberg-III, M.M. Alam Road, Lahore LAHORE Ebrahim Alibhai Tower, Shop No.02, Plot No.03, Block-7/8 Modern Cooperative Housing Society (MCHS), 061 0024 Karachi, Shahrah-e-Faisal Shahrah-e-Faisal, Karachi KARACHI 061 0025 Peshawar, Ashraf Road New Rampura Gate, Ashraf Road, Peshawar. PESHAWAR 061 0027 Muzaffar Abad (AJ&K) Secretariat Road, Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu & Kashmir MUZAFFARABAD 061 0030 Rawalpindi, City Saddar Road No.A/308- Jinnah Road (City Saddar Road) Rawalpindi RAWALPINDI 061 0031 Lahore, Johar Town Block -R-1, M.A. -

Sindh Bank Limited List of Operational Branches

SINDH BANK LIMITED LIST OF OPERATIONAL BRANCHES S.No. Branch Code Branch Name KARACHI BRANCHES 1 5303 ALLAMA SHABBIR AHMED USMANI ROAD (ISLAMIC) Shop No.2,3, & 4, Shaheen Heights, Block-7, KDA Scheme No.24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi 2 0329 BUFFERZONE NAGAN CHOWRANGI BRANCH Plot No. 32, Sector 11-H, North Karachi Township Scheme, Karachi 3 0364 BHAINS COLONY BRANCH Plot No. 217, Block-A, Cattle (Bhains) Colony Landhi, Karachi 4 0366 BAHRIA COMPLEX-II BRANCH Plot # Misc.-2, Bahria Complex-II M.T. Khan Road, Karachi 5 0375 BOHRAPIR BRANCH Shop No.3 & 4, Plot Survey No.88, RC.12 Ranchore Line Quarter, Karachi 6 0391 BALDIA TOWN BRANCH Plot No.667, Anjam Colony, Badia Town, Karachi 7 0302 CLIFTON BRANCH Ground Floor, St-28, Block-5, Federation House, Clifton, Karachi 8 0303 COURT ROAD BRANCH Ground floor, G-5-A, Court View Apartments, Opposite Sindh Assembly, Karachi 9 0318 CLOTH MARKET BRANCH Shop No.28, Ground Floor, Cochinwala Market, Bunder Road Quarters, Karachi 10 0369 CIVIC CENTER BRANCH Ground Floor, Civic Center, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi 11 0325 DHORAJEE BRANCH Plot # 35/243, Block 7&8, C.P. Berar Cooperative Housing Society, Dhorajee Colony, Karachi 12 0357 DHA PHASE-II BRANCH Plot No. 13-C, Commercial Area “A”, DHA Phase-II, Karachi 13 0338 DHA Phase-IV Shop # 1,2,3, and 4, Plot No.III 9th Commercial Street, Phase-IV, DHA, Clifton Cantonment, Karachi 14 0304 DHA 26th STREET BRANCH Plot No.14-E, 26th Street Phase 5 Ext. D.H.A, Karachi 15 0372 DR. -

X-Ray Facilities with License Valid Upto 30-06-2020 Name of Facility Address of Facility Sindh

X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr.No. Name of Facility Address of Facility Sindh District Karachi West 2710. Aga Khan Diagnostic Centre Adamjee Dawood Road, Kharadar, Karachi Aga Khan Family Health Sultanabad Colony, Near Gulbahar Police 2711. Centre Station, Golimar No.1, Karachi Aga Khan Family Health Gulzar-e-Rahim, BH-1, Block-5, Gulzar-e-Rahim 2712. Centre Colony, Metrovile, SITE Town, Karachi Plot No. 58, Sector A/3, Shahrah-e-Waqas, Near Al-Shifa Lab 2713. Saeedabad Post Office, Baldia Town, Karachi. 1726/1946, Muhala Ghous Nagar, Baldia Town, A-One Diagnostic Centre 2714. Karachi Amin Hayat Memorial Block-D, Main Shershah Road, Sabra Masjid 2715. Medical Centre Building, Shershah, Karachi 194, Sector D/3, Saeedabad, Baldia Town, Ayesha Diagnostic Centre 2716. Karachi Base Medical Centre (Dr. 2717. Shazia Shaheed Medical PN Dockyard, West Wharf Road, Karachi Centre) Plot No. 182, Sector 4-D, Near Mominabad Darul Sehat Medical Centre Police Station, Badar Chowk, Orangi Town, 2718. & Maternity Home Karachi Dr. Farzana Diagnostic Shop No.08, Sector A-3, Shahrah-e-Waqas, Near 2719. Centre Roobi Cinima, Saeedabad, Baldia Town, Karachi Dr. Mehdi A. Manji Plot No. D-52, Sector 5-D, Orangi Town No.5, 2720. Pathological Lab Opposite National Bank of Pakistan, Karachi Family Welfare Centre PNAD Mauripur, Hub River Road, Karachi 2721. Plot No. 511-24, Garden East, Business Fatimabai Hospital 2722. Recorder, Patel Para, Karachi X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr.No. Name of Facility Address of Facility Sector No. 4, Block-H, Commercial No. -

List of Conventional & Islamic Branches

LIST OF CONVENTIONAL & ISLAMIC BRANCHES AS OF MAY 2017 Sr. No. Branch Branch Name Address Code 1 0001 Main Branch Lahore (0001) Lahore Main Branch, 87, Shahrah-e-Quaid-e-Azam, Lahore. 2 0002 Main Branch Karachi (0002) Karachi Main Branch, Plot No: SR-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al-Rahim Tower, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 3 0003 Main Branch Peshawar (0003) Peshawar Main Branch, Property No: CA/457/3/2/87, Saddar Road, Peshawar Cantt. 4 0004 Main Branch Quetta (0004) Quetta Main Branch, Ground Floor, Al-Shams Hotel, M.A. Jinnah Road, Quetta. 5 0005 Main Branch Mirpur (AK) (0005) Mirpur Branch, Plot No: 35/A, Munshi Sher Plaza, Allama Iqbal Road, New Mirpur Town, Mirpur (AJK) 6 0006 Main Branch Hyderabad (0006) Hyderabad Main Branch, Shop No.6, 7 & 8 Plot No. 475 Dr. Ziauddin Road, Hyderabad 7 0007 Main Branch Gujranwala (0007) Gujranwala Main Branch, Khewat & Khatooni No: 78, Khasra No: 393, Near Din Plaza, G. T. Road, Gujranwala 8 0008 Main Branch Faisalabad (0008) Faisalabad Main Branch, Chiniot Bazar, Faisalabad 9 0009 Small Industrial Estate Branch Sialkot (0009) Small Industrial Estate Branch, BIV-IS-11--RH-Shop, Shahabpura Road, Small Industrial Estate, Sialkot 10 0010 Main Branch Gilgit (0010) Gilgit Branch, Raja Bazar, Gilgit. 11 0011 Defence Branch Lahore (0011) Defence Branch, G-3, Commercial Area, Defence Housing Authority, Lahore. 12 0012 Clifton Branch Karachi (0012) Clifton Branch, Shadman Centre, Block-7, Clifton, Karachi. 13 0013 Garden Branch Karachi (0013) Garden Branch, Silver Jubilee Center, Britto Road, Garden East, Karachi. 14 0014 Main Branch Rawalpindi (0014) Rawalpindi Main Branch, 102-K, Hospital Road/Bank Road, Saddar, Rawalpindi Cantt. -

Pakistan Hosiery Manufacturers & Exporters Association List of Eligible Voters 2010-2011

PAKISTAN HOSIERY MANUFACTURERS & EXPORTERS ASSOCIATION LIST OF ELIGIBLE VOTERS 2010-2011 SL# M.SHIP # NAME OF REPRESENTATIVE NAME OF COMPANY ADDRESS PHONE & FAX NOS. EMAIL NTN STN PH # 36902713- PLOT NO. 1-K-18,NAZIMABAD NO. 1, NEAR 1 0001 MR. ABDUL QADIR KAMANI 2-U INTERNATIONAL 4/36609855FAX # 36902716- [email protected] 1426721-7 11-00-6200-036-64 NAYAB CINEMA,KARACHI. 36621006 LA-6/A, BLOCK-22,FEDERAL "B" PH # 36342521-36345583FAX 2 0474 MR. JAWAID SULTAN JAPANWALA A & J APPAREL (PVT) LTD. [email protected] 0704117-9 11-00-1190-016-46 AREA,KARACHI. # 36313684 24/1, SECTOR 6-A, NORTH PH # 36974878- 3 0618 MR. MUHAMMAD YOUSUF ISMAIL A. ESSAK & SONS KARACHIINDUSTRIAL AREA, NEAR SABA 9/36956280FAX # 36908625- [email protected] 0670673-8 11-00-1190-178-46 CINEMA,KARACHI. 35206348 D-264, K.D.A. SCHEME # 1,BEHIND TIMES PH # 35075064-34860600- 4 0492 MR. ALTAF MAJEED A. MAJEED & SONS [email protected] 2942031-8 12-00-5212-025-64 MEDICOS (STADIUM RD)KARACHI. 2FAX # 35057907-34122222 PLOT NO. DP-36, SECTOR 12-D,NORTH PH # 36962733-34FAX # 5 0420 MR. FAHEEM AKHTER A.F. EXPORT [email protected] 2541424-7 17-12-5900-436-37 KARACHI IND. AREA,KARACHI. 36962735-36661871 PLOT # DP 84-85, SECTOR 12/C,NORTH PH # 36950355-56-57FAX # 6 0025 MR. MOHAMMAD RIAZ A.K. FASHION APPAREL INDUSTRIES [email protected] 0669324-5 11-00-1190-074-37 KARACHI INDUSTRIAL AREA,KARACHI 36950358-36993429 PLOT NO. 9, ST-13/1,SECTOR 6-B, NORTH PH # 36962361- 7 0586 MR. -

1. Persons Interviewed

Karachi Transportation Improvement Project Final Report APPENDIX-1 MEETINGS 1. Persons Interviewed During the Phase 1 study period, which is Karachi Transport Master Plan-2030, JICA Study Team (JST) has been visited different organizations and Departments to collect data and also meet the officials. The list of these officials and their department/organization are given below 1.1 CDGK Administrator/ DCO, City District Government Karachi 1.1.1 KMTC Director General, Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK Director, (Planning & Coordination) Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK. Director (T), KMTC, CDGK 1.1.2 Master Plan Executive District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK 1.1.3 Transport & Communication Executive District Officer, Transport Department , CDGK District Officer (Parking & Terminal Management), Transport & Communication Department (TCD), CDGK District Officer, Policy, Planning & Design, Transport & Communication Dept. CDGK 1.1.4 Education Department Executive District Officer, Education(School) , CDGK 1.1.5 Works & Service Department Executive District Officer, W&S , CDGK 1.2 DRTA Superintendant, District Regional Authority, CDGK 1.3 Town Administration Administrator, Keamari Town Administrator, Baldia Town Administrator, Bin Qasim Town Administrator, Gulberg Town Administrator, Gadap Town Administrator, Gulshan Town Administrator, Jamshed Town Administrator, Korangi Town Administrator, Landhi Town Administrator, Liaquatabad Town Appendix 1 - 1 Karachi